A sad economy without much hope

The quote in today’s title is from EY’s Cherelle Murphy, who used the phrase to describe last week’s uninspiring national accounts data and how “this level of spending” by our various governments, while flattering the overall figure, “won’t deliver macroeconomic stability and drive sustainable long-term growth”:

“The private sector needs more from their governments than short-term fixes to today’s problems. While policies like the $900 million productivity incentives fund and the National Competition Policy initiative are welcome, a focused agenda that drives GDP growth from the private sector is crucial – now more than ever.”

I agree, and it’s a bit disheartening that Murphy could only name two positive policies (for what it’s worth, that’s where my list stops too). But it also gets to a point I made last week: namely that everyone should be less concerned about Australia’s ongoing per capita recession because of the compositional changes that have distorted those figures, and more worried about the ongoing private sector recession and what’s (not) being done about it.

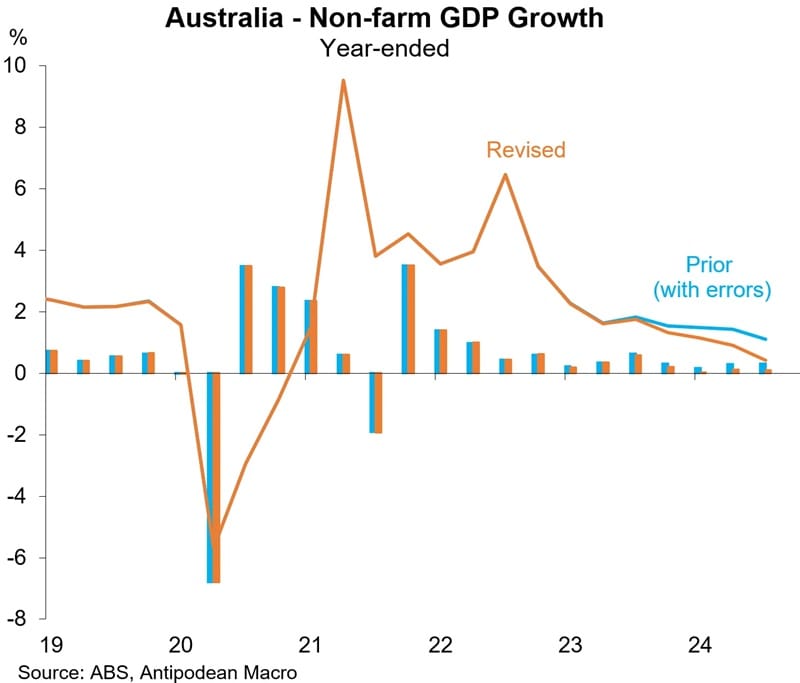

Indeed, given the recent upward revision to farm output, Australia may already be in a technical recession this quarter despite strong population growth and record government spending:

Unfortunately Treasurer Chalmers doesn’t appear to care, preferring to take credit for the small amount of growth in real GDP:

“Without the contribution from public final demand, the economy would have gone backwards, and that’s been a common feature of the national accounts this year. Our view is that we would rather be part of a soft landing in our economy than to clean up after a hard landing.”

Chalmers is technically correct that public final demand, i.e. government spending, is raising GDP. After all, the GDP equation is C + I + G + (X-M), so if you increase G and hold the others constant, you will by definition raise GDP.

But that’s also where his claim falls apart. Everything else is rarely constant, so accounting identities tell us precisely nothing about empirical questions like whether Australia would have grown in the absence of Chalmers’ profligacy.

For all we know, the increase in G might be reducing C and I by an even greater amount than the growth in G, because of what economists call crowding out. Basically, when aggregate demand is running hot – as it has been in Australia – the money the government is using to build its infrastructure projects, or pay for its cost of living handouts and other gimmicks, often comes at the expense of private spending.

Moreover, because our governments are borrowing to pay for it all, they’re not only pulling resources from other sectors of the economy (e.g. goods, services, labour) but are also driving up borrowing costs for private actors through competition for capital.

Put it all together, and the contribution to GDP from public final demand may well have reduced private consumption and investment by an even greater amount, explaining at least part of Australia’s private sector recession. And given what our governments are spending on, it’s also well within the realm of possibility that they’re making inflation worse, ensuring that interest rates stay higher for longer.

Hear me out. The equation of exchange is MV = Py, where M is the money supply, V is the velocity of that money (how often M is exchanged), P is the price level, and y is real output (real GDP). To the extent that government spending is reducing real output by crowding out the private sector with its consumption, y will be lower than otherwise. That means if M and V haven’t changed, then by definition P – prices – must increase.

Essentially, if our governments had shown restraint and not crowded out the private sector to the extent that they have, the recent inflation wouldn’t have been as severe.

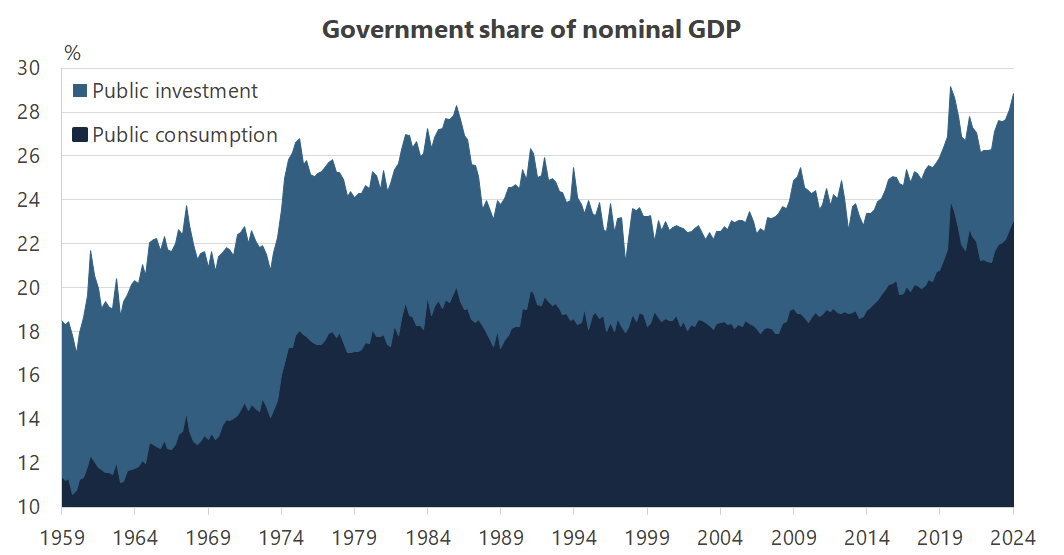

And boy have they spent. Excluding the pandemic when the government’s share of GDP reached 29.2%, September 2024’s 28.8% was officially the highest on record. It’s not like it was all investment, either; public consumption also hit a record high in September (again, excluding the pandemic), as state and federal “cost of living” support really kicked into another gear:

The large increase in public consumption, which is now 23% of the economy, is crowding out the private sector and does not bode well for future growth and productivity. And given that it’s all being paid for with borrowed money we’re essentially eating the seed corn, leaving very little for a future crisis.

Yes, it’s miserable

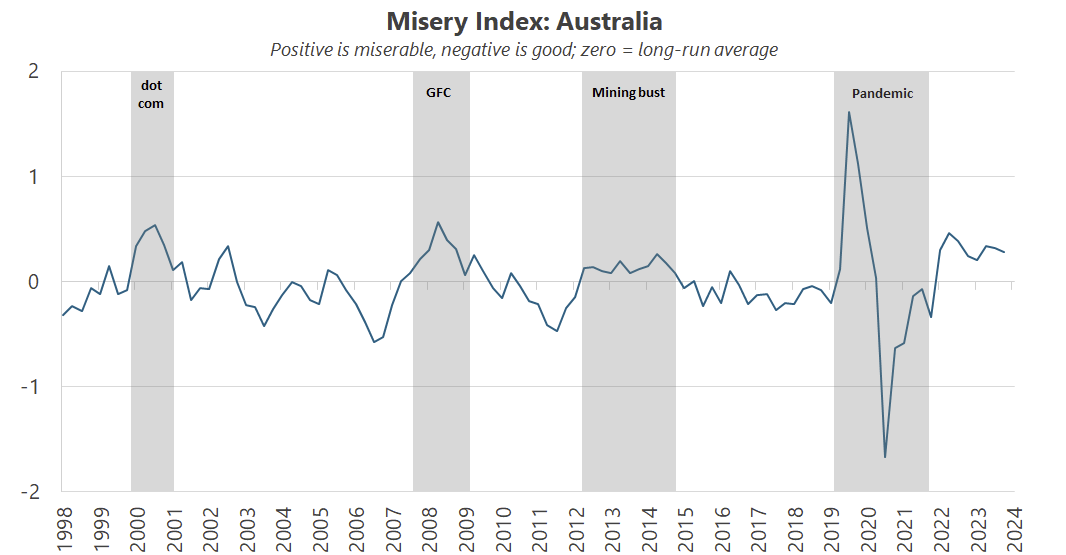

Australia’s economy isn’t just sad; it’s miserable. My preferred version of the so-called Misery Index is the rate of inflation (trimmed mean to avoid cost of living shenanigans) plus the unemployment rate minus the real GDP growth rate. It has never looked so bad as it does today:

At no point this century has Australia’s Misery Index been this high above the long-run average for this long. It was higher at the start of the pandemic, during the peak of the global financial crisis, and very briefly during the dot-com bust. But in all of those episodes, it promptly reversed.

Really the only comparable period is the terms of trade bust that ran from 2013-15, although even then the deviation from the mean was considerably lower than it is today.

So, what can be done about it? Instead of obsessing over GDP and a “soft” or “hard” landing the focus should be on raising living standards, and unless you’re spending big on infrastructure that will raise future productivity, you don’t do that by increasing the government’s share of the economy from already-elevated levels.

Such spending will at best postpone the inevitable adjustment needed for the private sector to recover, as it will change people’s expectations about future tax burdens and the rates of inflation needed to pay for it all, affecting their behaviour today.

Yes, this government has “created” a lot of jobs. But sustainable, productive jobs don’t come from governments giving some people money now while simultaneously borrowing it from other people to pay back later. They come from entrepreneurial activities, where individuals and firms work to discover where and at what they’re most productive, and then trade that output with other people who are doing similarly. There are large transaction costs and knowledge problems involved – frictions – and government policy can help by ensuring those are as low as possible.

Moreover, if a future government was serious about fixing the mess, it could set fiscal policy to a level that changes expectations sufficiently to trigger an expansionary fiscal contraction:

“[If the fiscal consolidation is read by the private sector as a signal that the share of government spending in GDP is being permanently reduced, households will revise upward the estimate of their permanent income, and will raise current and planned consumption.”

In other words, start cutting G so that C and I can breathe again!

Getting out of the way

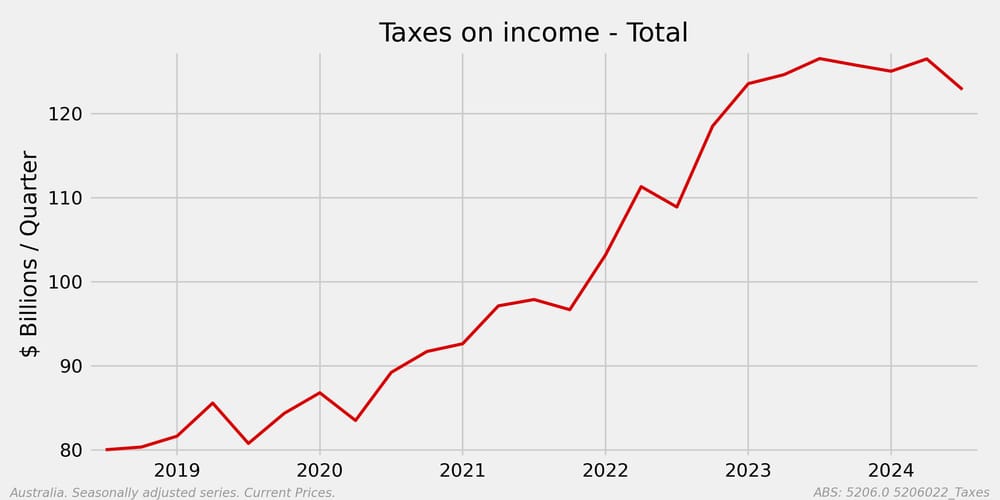

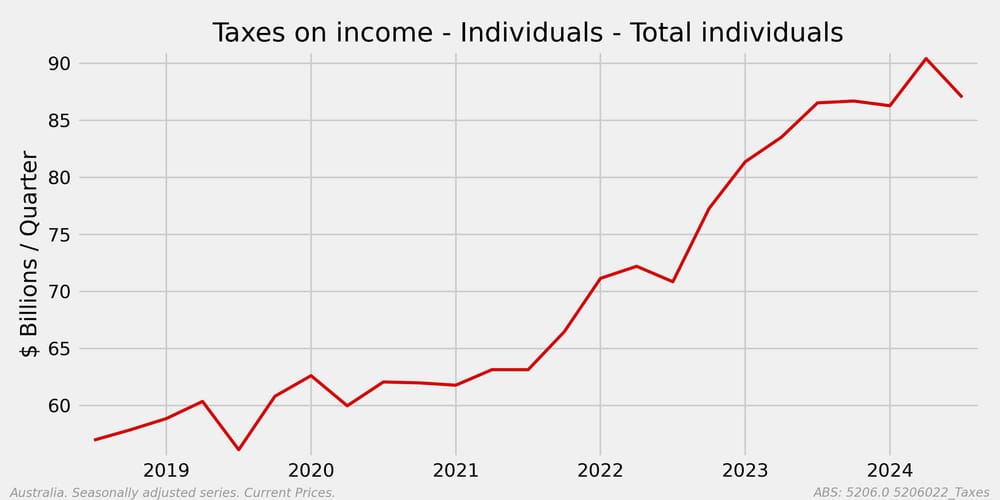

If something doesn’t give, then it won’t be long before Australia finds itself well and truly along the road to a European-style stagnation. Things like the rigidification of our labour markets dressed up as industrial relations reform. Suffocatingly high taxes on income. Increased public spending on ’nice to have’ entitlements like the NDIS, rather than productivity-boosting investments. And a general increase in the unproductive non-market share of the economy.

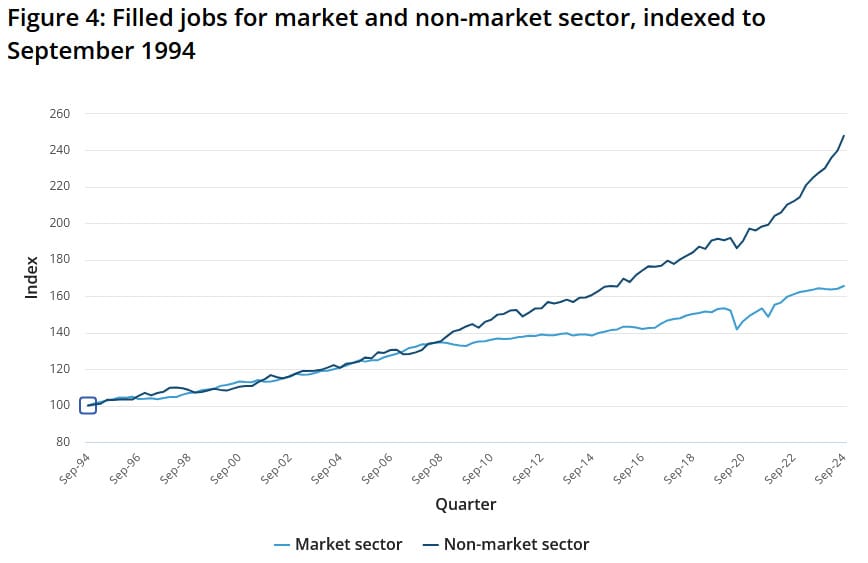

Of course, some of those non-market jobs were due to a much-needed shift away from expensive consultants and towards bringing expertise back in-house – the Morrison government had truly taken that model too far. But those jobs make up fewer than 10% of the non-market jobs added over the past year.

Most of the new non-market jobs aren’t bureaucrats but “Health care and social assistance” (HCSA) workers, an industry that has grown astronomically since the introduction of the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) in 2013.

In the past year, the HCSA sector alone contributed nearly 60% to Australia’s total jobs growth. Add that to the rest of the non-market sector and it explains almost all of Australia’s robust labour market:

“In the last two calendar years, 87 per cent of all employment growth in the economy has been in the ’non-market’ sector – public administration and safety, education and training, and healthcare and social assistance – despite it accounting for just 30 per cent of jobs. In the September quarter, it accounted for 91 per cent of all employment growth.”

Many of those are no doubt essential; we are, after all, an aging country and so some kind of care for the elderly versus productivity and growth trade-off was always inevitable. Many are also a complete waste of taxpayers’ dollars, scooping up the seemingly bottomless pit of NDIS funds for no good reason.

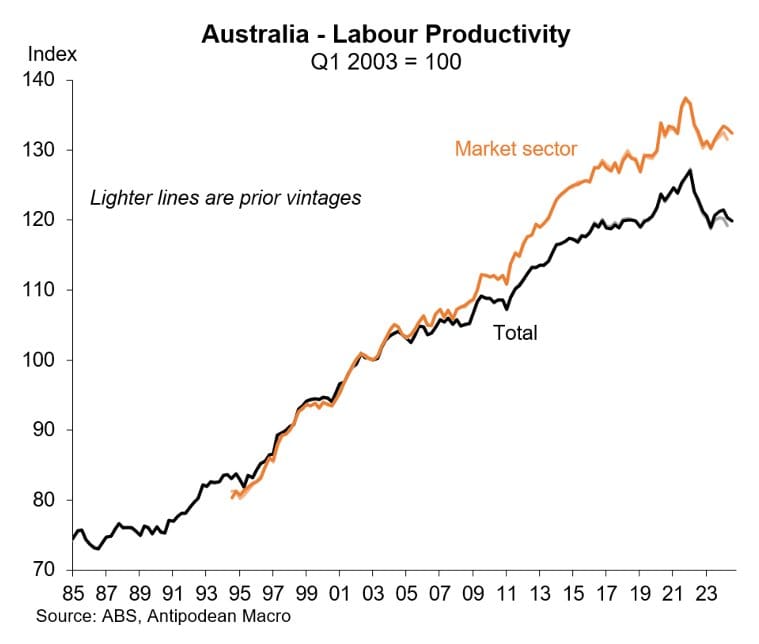

But regardless of the merits of these jobs, the fact is they’re not very productive, so the rest of the country must, by definition, work harder and longer to pay for them to maintain living standards:

That means governments also have to work extra hard to stop suffocating the golden geese that produce the eggs needed to support these jobs.

And what has the Albanese government done on that front? Very little. In fact, I’d argue that even when it’s spending on transfers, it’s doing it in a fairly inequitable way.

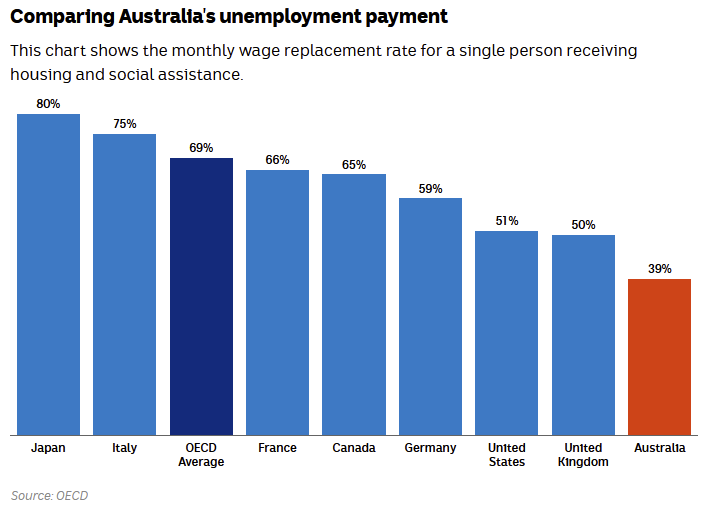

For example, the waiving of HECS debt that will disproportionately benefit people who will earn more in their lifetime than the taxpayers funding it, cost the government as much as running the public hospital system for a year, or a permanent increase in the JobSeeker allowance by $2,000 a year.

It’s not like Australia’s unemployment scheme is overly generous or anything:

Similarly, the Albanese government’s childcare reforms that introduce a flat daily fee do nothing about supply so will “end up leading to price increases”, with most of the benefits flowing to high-income families.

Meanwhile, the tax take on incomes – i.e. productive labour – is close to record highs, despite the Stage 3 cuts:

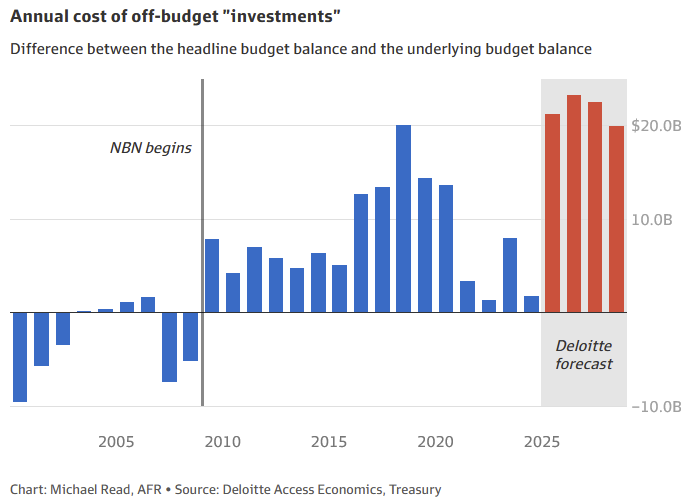

A lot of spending is also being hidden from voters, with everything from HECS debt forgiveness to a Future Made in Australia being classified as “investment” to keep it out of the Budget’s underlying deficit figure.

Put it all together, and you get the mess that Australia is in today. It didn’t start with the Albanese government – I’d even argue that the rot started with John Howard, who was blessed with rivers of gold that flowed from prior reforms and the emergence of China and simply spent it – but Albo and Chalmers have certainly taken full advantage of being Australia’s “luckiest ever government”.

The problem is the luck may eventually run out, even for the Lucky Country.

Comments

Comments have been disabled and we're not sure if we'll ever turn them back on. If you have something you would like to contribute, please send Justin an email or hit up social media!