A sticky, stagflationary mess

The Swiss National Bank (SNB) became the first advanced economy central bank to cut its cash rate last week, from 1.75% to 1.5%, after its “the fight against inflation” had proven to be “effective”:

“For some months now, inflation has been back below 2% and thus in the range the SNB equates with price stability. According to the new forecast, inflation is also likely to remain in this range over the next few years.”

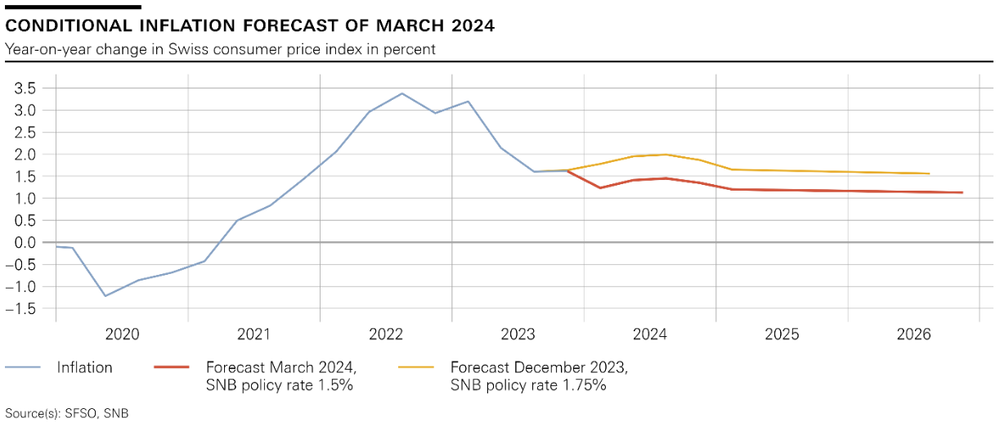

Here’s a helpful chart showing the SNB’s latest inflation forecast (red line), which it expects to remain below 2% despite the reduction in the cash rate:

According to the SNB, the slowdown in goods inflation has driven headline inflation back below 2%, while “higher prices for domestic services” remain an upward force. The appreciation of the Swiss franc in real terms, due in part because the SNB had been actively selling its large holding of foreign exchange, also helped to moderate inflation:

“Tightening monetary conditions in this way had various advantages. First, the appreciation of the Swiss franc significantly weakened the transmission of inflation from abroad. The increase in inflation in Switzerland was therefore considerably smaller than in other countries. Second, we had to raise our policy rate only moderately by international comparison. This also prevented a stronger rise in the mortgage reference interest rate.”

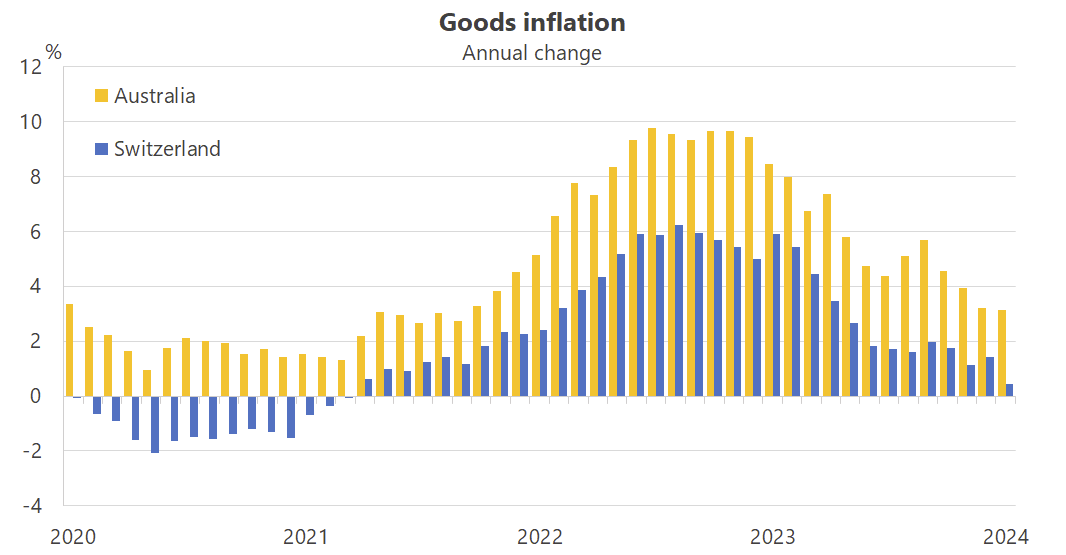

To give you an idea of how that compares with Australia, over the past two years the Australian dollar has gone from buying around 69.5 Swiss francs to 58.4, or a depreciation of 16% – similar to what we’ve lost against the US dollar (about 15%). The stronger exchange rate in Switzerland was one reason why goods inflation didn’t take off to the same extent as it did in Australia: a weaker currency in an economy such as Australia, according to the RBA, “will contribute to a higher level of consumer prices in Australia”.

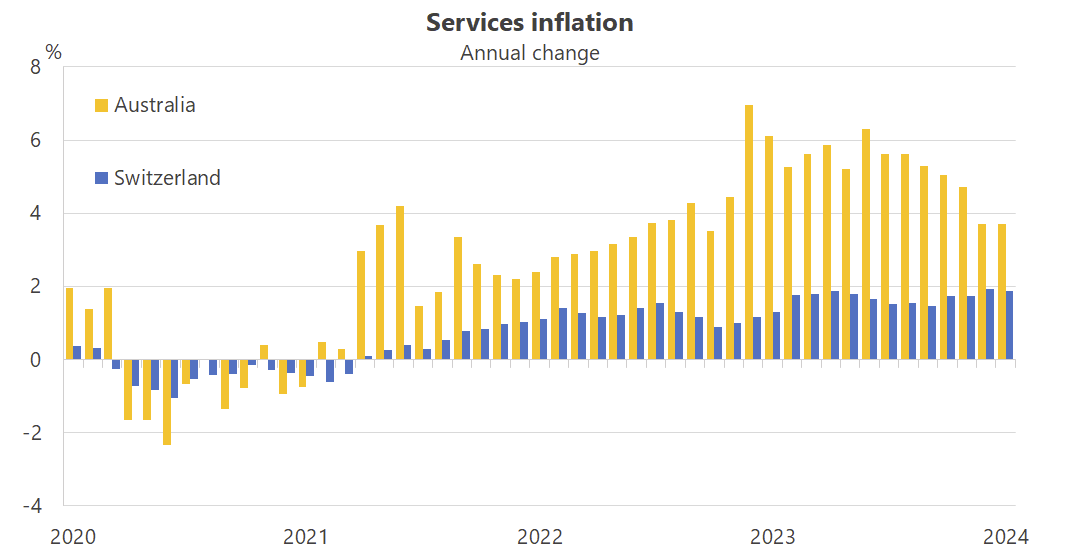

But Switzerland also experienced considerably less services inflation than Australia. Compared to January 2020 (i.e. pre-pandemic), services prices are just 3.9% higher in Switzerland compared with an 11.8% rise in Australia. In other words, prices here rose around three times faster than they did for the Swiss. That ratio was similar for goods inflation, with 19.4% growth in Australia versus 8.2% for the Swiss, making our increase around 2.4 times greater.

Australia’s inflation was inevitable

For me, that’s a tick for the fiscal theory of the price level: the additional pandemic spending done by governments in Australia was about 18.5% of GDP (as at September 2021), while Switzerland’s governments spent less than 8% of their GDP – or a ratio of roughly 2.3 to 1. When you spend nearly 20% of your GDP on cash handouts or equivalents (e.g. JobKeeper), much of it financed with newly printed money, you shouldn’t be surprised when you get inflation.

But Switzerland is not even close to being a perfect comparison for Australia. Its role as European financial hub and safe haven means the SNB gets away with a lot more exchange rate shenanigans than the RBA would in Australia. For example, people like holding Swiss francs in times of uncertainty. Australian dollars? Not so much.

The Swiss economy is also structurally different to ours. It contains a huge gold industry that refines 70% of the world’s gold, despite the country having no gold mines of its own; has almost no agriculture (less than 1% of GDP); and 20% of its economy is involved in manufacturing things like “watches, motors, generators, turbines and diverse high-technology products” (versus ~6% in Australia).

Essentially, it’s not a great case study to be using for a cross country comparison with Australia. But the SNB’s move to cut rates did get me thinking: will inflation in Australia prove to be like that of Switzerland, i.e., a once-off change in the price level, with goods inflation tapering off by itself along with some ‘stickiness’ in the services sector, or do we have a different outcome in store for us?

How sticky will inflation prove to be in Australia?

The Bank for International Settlements (BIS) released a report in March called Sectoral price dynamics in the last mile of post-Covid-19 disinflation. In normal person language, the BIS wanted to know whether services inflation will prevent central banks getting inflation down to their targets, “given the relative stickiness of services prices and past relative price trends”.

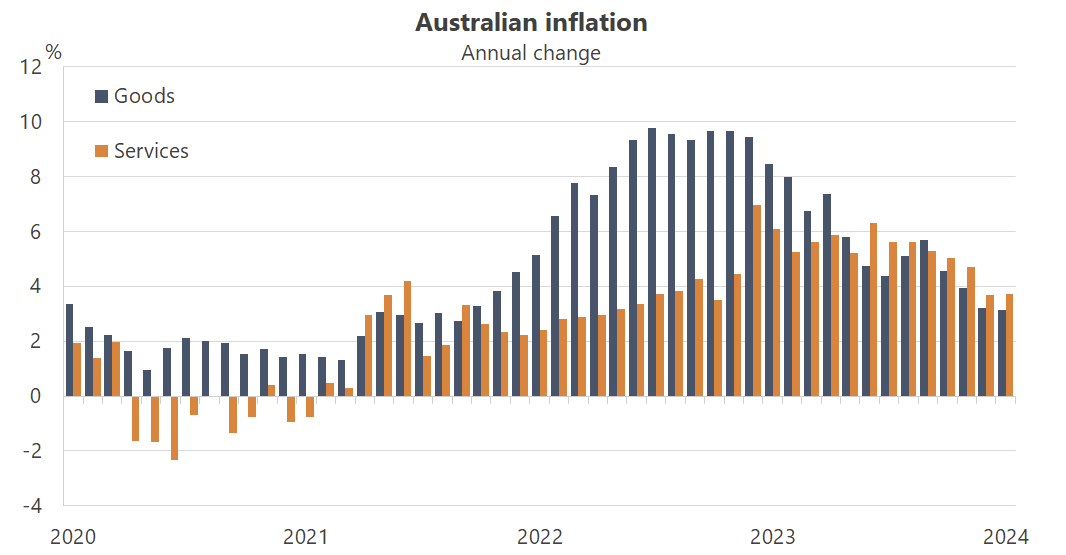

It’s an important question. In Australia, most of the inflation we experienced in 2021-22 was from goods. But the growth rate in the prices of services has now passed that of goods, the latter of which – barring a collapse in the Australian dollar exchange rate – should continue to fall as aggregate demand eases.

Services inflation is largely domestically-driven. Given how labour intensive services are, their prices are quite sensitive to changes in wages. They’re also generally not somewhere we can look for productivity gains due to what’s known as Baumol’s cost disease. Essentially, wages in the services sector rise not necessarily because of higher productivity (a rock concert still takes roughly as much time, and needs about as many people to perform, as it did 50 years ago) but because to incentivise people to sing songs or pour coffee instead of driving forklifts, wages need to be attractive enough for them to make that trade-off. In the words of Baumol (1967):

“If productivity per man hour rises cumulatively in one sector relative to its rate of growth elsewhere in the economy, while wages rise commensurately in all areas, then relative costs in the nonprogressive sectors must inevitably rise, and these costs will rise cumulatively and without limit… Thus, the very progress of the technologically progressive sectors inevitably adds to the costs of the technologically unchanging sectors of the economy, unless somehow the labour markets in these areas can be sealed off and wages held absolutely constant, a most unlikely possibility.”

The services sector in Australia employs around 88% of our labour force. As we get wealthier and our productive sectors keep improving, more and more labour gets pulled to the services sector to maintain the ratio between goods and services demanded by consumers. Again, here’s Baumol:

“By definition, labour productivity grows significantly faster in the progressive sector than in the stagnant sector, so to keep a constant proportion between the two sectors’ output, more and more labour has to move from the progressive sector into the stagnant sector.”

Despite the word “disease” being in the name, there’s nothing inherently wrong with an economy moving in that direction. Plenty of services, such as finance, ICT and transport, are still quite productive. Many of the others with limited scope to improve productivity are still market-facing, and who are we to say what people should and shouldn’t spend their hard-earned on?

There is a legitimate policy concern about those that face limited competition, such as government and government-provided services including health and education, but that’s a much deeper issue that I won’t get into today. The point I’m trying to get at is the BIS is right to be concerned about services inflation being sticky, and so should we in Australia. Given its large share of employment and the fact that “wages are rising at rates inconsistent with inflation targets given sluggish productivity growth”, services inflation is already proving to be stickier than goods inflation.

It’s all about wages

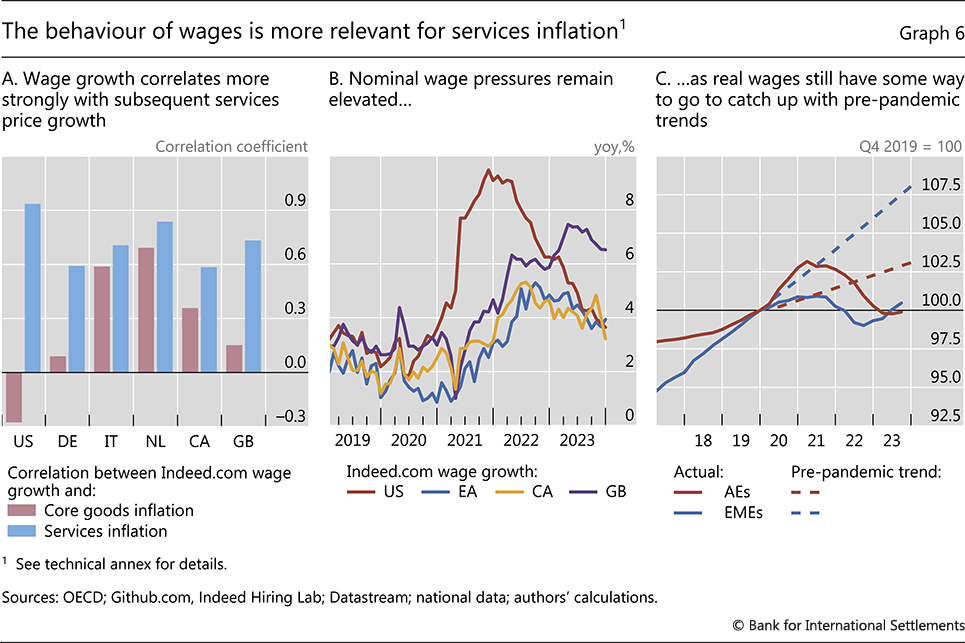

In the long run, real wages are strongly linked to productivity, so any attempt to boost real wages in aggregate, without a commensurate increase in total labour productivity, risks prolonging inflation and putting people out of work. It’s also a bit of a self-reinforcing cycle, as “the longer inflation remains above target”, the more likely it “could lead to an adjustment in wages”. The BIS provided these charts showing that nominal wages are important for the cost of services, with the blue columns on the left panel especially important:

Australia has a relatively high rate of collective bargaining agreements compared to the OECD (61% versus 32%), and the duration of those agreements is three years, versus the OECD average of 12-24 months. That means is Australia is more susceptible to nominal wage growth being locked-in than countries such as the US.

If the inflation we experienced following the pandemic was a once-off level change to partially pay off the enormous amount of fiscal spending for which taxes were never actually raised – nor intended to be raised – then we all got a bit poorer because of it; it was wealth destruction on a grand scale. In such an economy, a decline in real wages should be expected: the inflation made us all poorer, so real wages need to adjust downwards. The risk of sticky inflation then comes if, in response to the inflation, governments attempt to lock-in nominal wages growth above the true level of productivity to restore workers’ “lost” wages. But doing so will mean interest rates have to stay higher for longer, growth will be lower for longer, and if real wages rise too much, we could also be in store for significant disemployment effects – i.e., a sticky, stagflationary mess.

As the BIS concluded:

“Disinflation is in progress in 2024, but the job is not yet done. The analysis in this special feature suggests that the larger contribution of services to inflation could sustain underlying inflationary pressures in the short term. If so, monetary policy would have to stay tighter to achieve a given inflation objective than would be the case if inflation mainly reflected faster growth in goods prices.”

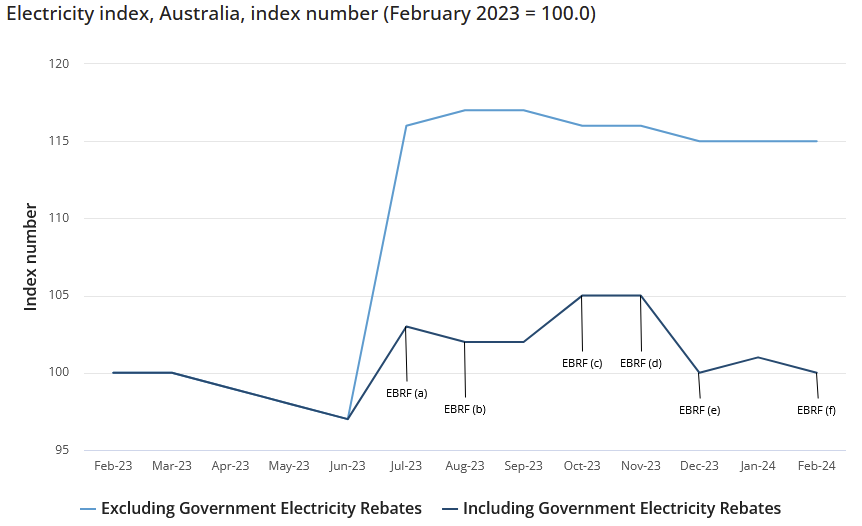

Monetary policy in Australia hasn’t been all that tight; at 4.35%, the cash rate only recently passed the quarterly rate of inflation of 4.1%. Admittedly it has been above the monthly rate for all of 2024, although government support has played a key role in temporarily suppressing some components of the CPI basket, such as energy.

Yet nominal GDP growth, a measure of aggregate demand, has slowed considerably, suggesting that demand-induced inflationary pressures should start easing further. Another tick for the fiscal theory of the price level.

But that doesn’t mean measured inflation will go away. Nominal wages have been increasing quickly in recent months and are now growing at a rate faster than consumer prices. Real wages are now rising, which is obviously a good thing in a healthy economy, but given the rigidities in Australia’s labour market they could very quickly end up well above market-clearing wage rates, i.e. those linked to labour productivity.

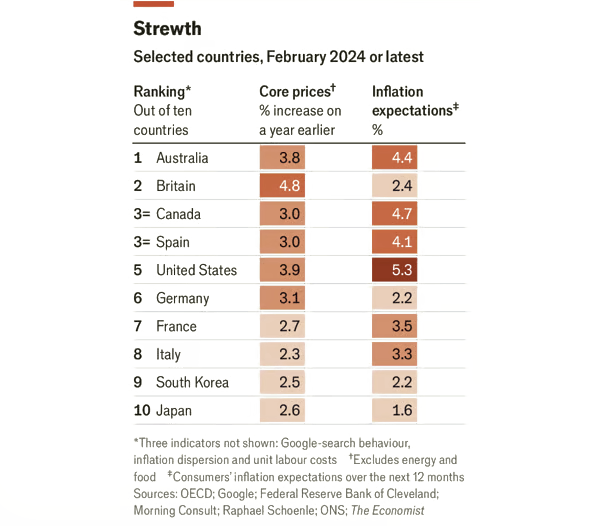

Labour costs are the key component in services inflation, so it’s hard to see inflation falling back to within the RBA’s target of 2-3% any time soon. According to The Economist’s latest ( 27 March) measure of “inflation entrenchment”, which includes “core inflation, unit labour costs, ‘inflation dispersion’ (the share of consumer prices that are rising by more than 2% year on year), inflation expectations, and Google-search behaviour, Australia tops the rankings.

Sticky inflation in Australia would mean the RBA will have to keep the cash rate higher for longer, and with aggregate demand slowing, higher real wages could cause some people to be forced out of employment.

The government won’t be able to do much about that; nominal wage rigidity is very much a feature of most economies. But this government looks especially vulnerable to it, given most of its labour market actions to date have been to strengthen rigidity. That’s perhaps a good thing during normal times, but in an inflationary environment it will reduce the ability for businesses to adjust to falling aggregate demand on the wages, rather than employment, margin.

Treasurer Chalmers has also indicated that he doesn’t fully understand what’s going on, based on his recent calls to raise the minimum wage:

“Our submission will reflect our desire to ensure that low-paid workers don’t go backwards — this is consistent with the submissions we’ve made to the Fair Work Commission on earlier occasions.

…

Low-paid workers are disproportionately impacted by these cost-of-living pressures — that’s why we want to see them earn more… so they can deal with these cost-of-living pressures in our economy.”

Wages are a price – a price for labour – and by meddling with prices, governments can cause unintended consequences. One in four Australian workers are on an award linked to the minimum wage, many of them in the services sector. All else equal, you can’t just mandate higher wages without affecting the labour market. In this case, by mandating that some workers be paid a bit extra each hour, they could inadvertently be reducing other people’s hourly wage to zero, and be making inflation stickier than it needs to be, ensuring that interest rates stay higher for longer. Average labour productivity might eventually increase, but only when the least productive workers are forced out of employment.

If the Albanese government truly wants to help low-paid workers who need the support without causing potentially large side-effects, it should target support directly at those people. It already has programs it can do that through, such as JobSeeker and Commonwealth Rent Assistance, which are both cash-in-hand so won’t be completely captured by landlords. It could even time-limit any increases or pay them as a cost of living ‘bonus’. Just don’t mess with wages and prices!

But perhaps most importantly, the government should stop deficit spending – which is what got us into this mess in the first place – because the interest on its debt is only going to add to future inflation. Sure, it might run a headline surplus this year because of inflation (bracket creep), high commodity prices and “accounting gimmicks”, such as classifying a bunch of spending as “investment” to exclude it from the Budget’s underlying balance. But:

“What matters is structural surpluses over the 10 to 20 years that it takes to repay debt.

Inflation fundamentally comes from more government debt than people think the government will be able to repay, but to repay over the long, long, long run.”

The Albanese government won’t change its spots this close to an election. But whichever party wins power in 2025 will have to contend with structural fiscal deficits as far as the eye can see, and the prospect of sticky inflation. Fixing it won’t be an easy task.

Comments

Comments have been disabled and we're not sure if we'll ever turn them back on. If you have something you would like to contribute, please send Justin an email or hit up social media!