A troubling economic scenario

This post builds on a discussion from earlier this month on what ails the Australian economy and what our governments can do about it. But before getting into that, I want to point out that the economic situation is not quite as bad as people are making it out to be: the unemployment rate is 4.0%; inflation has cooled (but is still far too high); mortgage stress is falling; real household incomes are where they were pre-pandemic; and a large part of the ongoing GDP per capita recession is due to temporary statistical quirks, making it a misleading indicator for what the average Australian is feeling right now.

But that doesn’t mean it couldn’t be better. Real growth truly has plateaued, largely due to a long-term lack of reform at all levels of government, the unwinding of the most recent mining boom, and the growing share of non-market activity in the economy. It all adds up to stagnant productivity growth (zero since 2016), which is the key ingredient for improving long-run living standards. Basically, we are where we are today because of decisions made (or not made) by this and previous governments going back to at least John Howard.

The great Adam Smith once observed that there’s a lot of ruin in a nation, meaning that countries can endure significant economic mismanagement before reaching a crisis point. In Australia, the amount of ruin really took off when then pandemic hit and former PM Scott Morrison, with the support of the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA), decided to run the economy hot. Rather than wind back the pandemic-period’s extensive government spending, the Albanese government has instead embarked on its own big government adventure.

While it has done some good – e.g. its pharmacy reforms and ongoing attempt to restore the National Competition Policy – it has blown most of its political capital on gimmicks like several billion dollars worth of debt-financed “cost of living” handouts, imposing social media age limits, Build to Rent/Help to Buy, student debt relief and childcare subsidies for the relatively well-off, and its refusal to legalise the safest, most reliable form of clean energy that we know of: nuclear.

Then who could forget its revival of the policy failures of the 50s, 60s, and 70s in the form of a Future Made in Australia, along with an increase in its spending share of the economy to an all-time high 26.5%, with a projected 5.7% increase in real spending this financial year alone.

But it’s not all the Albanese government’s fault.

Running it hot

While Scott Morrison and his then-Treasurer Josh Frydenberg deserve their fair share of the blame for where Australia’s macro economy is at today, they certainly weren’t alone in their decision to run the economy too hot. In fact, most advanced economies around the world did pretty much the same thing, which US commentators dubbed “run it hot economics” at the time. Inspired by the fringe Modern Monetary Theory or MMT movement, it ended how orthodox economics predicted it would:

“On the fiscal side, extravagant spending greatly increased government indebtedness. On the monetary side, running the printing press to keep interest rates low flooded financial markets with liquidity. The predictable result was too much money chasing too few goods — the classic recipe for dollar depreciation, better known as inflation.”

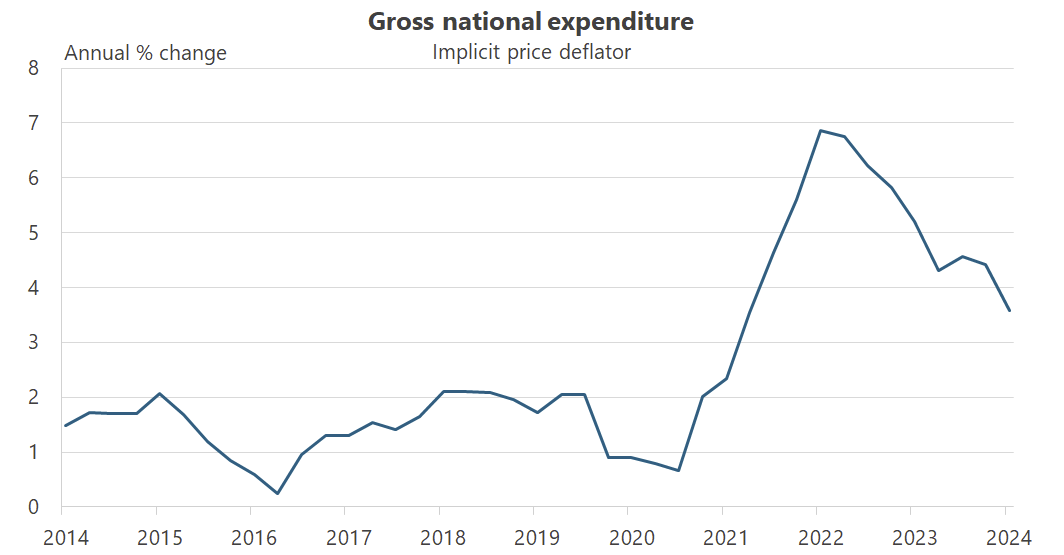

In Australia, the demand surge caused by fiscal and monetary stimulus is clearly visible in the national accounts:

I asked Claude what might be going on in a country where the Gross National Expenditure Implicit Price Deflator (GNEIP) – a crude measure of inflation that captures the average price changes across all goods and services, so cannot be as easily manipulated by government policy like the Consumer Price Index (CPI) – is growing at 3.6%, while real GDP is 0.8% and real GDP per capita is -1.5%.

It said that taken together, such data “paints a troubling economic scenario”:

“This combination of low real growth and high price increases is particularly challenging because it suggests the economy is not generating additional value, but prices are rising significantly. This can lead to reduced living standards, decreased business investment, and overall economic stress.

It’s a red flag for economic policymakers, indicating a need for careful economic management to address both the low growth and high inflation simultaneously.”

I think that gets to the problem of the Albanese government. Did it cause the mess? Not entirely; plenty of damage was done by the (now) opposition. But it has done very little to fix it, and plenty to worsen it. It’s essentially making the same mistakes Joe Biden’s government made with its “continued fiscal follies”:

“As election day exit polling revealed, the electorate repudiated the modern monetary theory narrative. Americans are fed up with over-credentialed experts inventing new reasons to ignore basic economics. The laptop class has only itself to blame for elevating these fringe theories, thereby facilitating Trump’s electoral comeback.”

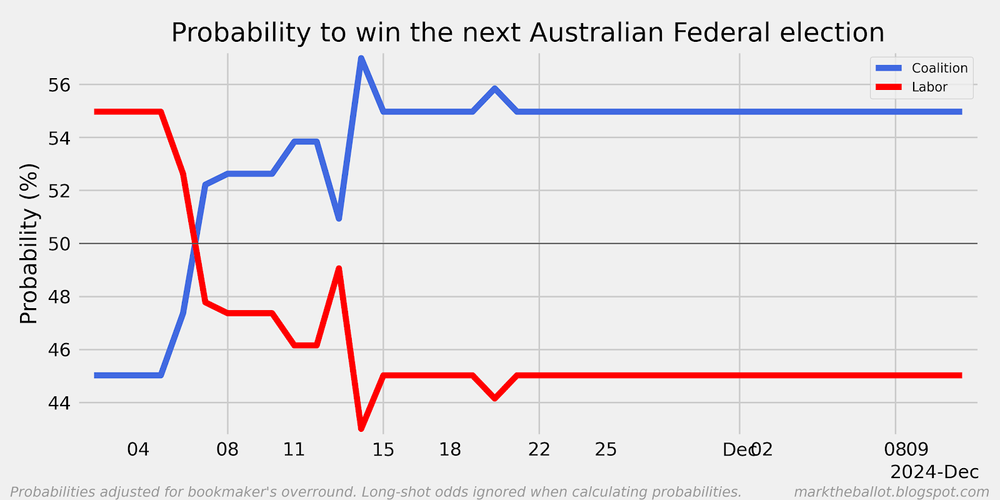

Recent polling suggests that voters agree. The federal Labor Party’s primary vote is down to 27%, and Anthony Albanese has an unenviable 50% disapproval rating:

“A majority of respondents (51%) said Australia was on the wrong track, with just 31% saying it was on the right track and 18% unsure.

Almost half the sample (47%) said 2024 had ended up being worse than they expected at the beginning of the year, compared with just 20% who said it was better, 30% who said it was as expected and 3% who preferred not to say.”

For context, Albanese’s polling numbers are now as bad as Scott Morrison’s were prior to the last election, and betting markets have the Coalition at 55% favourites to win, with the big swing occurring around the time of the US election:

Labor insiders are even beginning to attack party policies in public, such as this scathing critique from former ACTU president and federal Labor MP Jennie George:

“Australia is the only G20 country that maintains a nuclear ban. It has been 26 years since the Howard government agreed to the Greens’ amendment, a condition of proceeding with a research reactor at Lucas Heights in Sydney’s southwest. There’s no rational reason for maintaining the ban.

…

The Albanese government wants us to believe it governs in the Hawke tradition. On nuclear energy they are miles apart.

Bob Hawke believed in the contest of ideas and as a known supporter argued we should ‘put all the passions and prejudices to one side and look at the facts’. It would be a fitting tribute to his legacy for the government to lift the nuclear ban, make public its whole-of-system costings and lead a meaningful debate on an issue of such national importance.”

In a world where incumbents are being voted out, rather than oppositions being voted in, it’s certainly going to be an interesting few months!

Inflation, inflation, inflation

It’s too late for the Albanese government to materially affect Australia’s economic outcomes this late in its term. From now until the date of the election, both parties are going to be in full-on campaign mode. But whomever wins will need to change tack, and quickly.

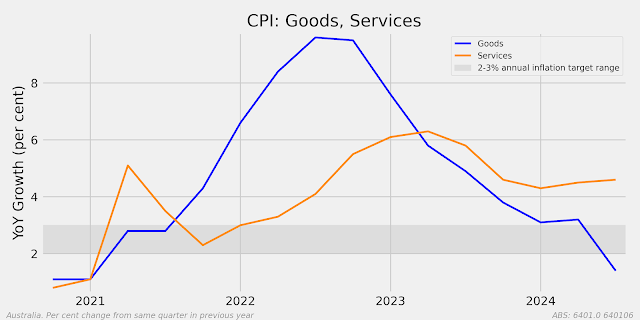

The first thing a new government needs to do is get on top of inflation. I don’t mean cash handouts dressed up as “cost of living support”; I mean meaningful fiscal restraint and reform that eliminates perpetual structural deficits.

An influential 2023 paper by Barro and Bianchi found a strong correlation between government pandemic spending and subsequent inflation. If the same conditions still hold, then a plan to credibly get the budget back in balance is required to bring inflation back down in a timely fashion. I italicised credibly because expectations matter for inflation: if people don’t expect lower taxes in the future, they will change their behaviour today.

Getting on top of inflation will also be important for re-election. Voters really dislike inflation, because it’s costly. A 2001 paper by Di Tella, MacCulloch, and Oswald found that “the well-being cost of a 1-percentage-point increase in the unemployment rate equals the loss brought about by an extra 1.66 percentage points of inflation”.

Basically, if the government and RBA’s efforts to preserve a percentage point of employment by ‘running it hot’ meant inflation was 1.66 percentage points higher, then it has done the country a disservice; it has reduced welfare. Given that services inflation is proving sticky, the majority of jobs added over the past year have been in non-market roles, and that the Phillips Curve (an inverse relationship between inflation and unemployment) doesn’t hold in the long run, that certainly looks to be the case.

And who will voters blame? The incumbent government, as they did all over the world in 2024.

Feeding the golden geese

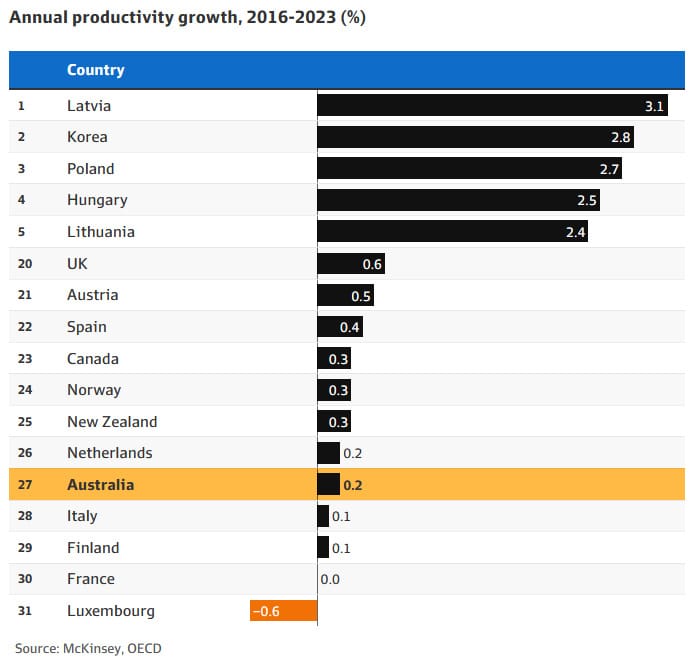

The next most urgent priority is to get productivity moving. A recent report from McKinsey allegedly said that:

“Australia has had zero labour productivity growth since 2016, showing up in higher costs for business and consumers, weaker real incomes and declining competitiveness for investment.”

‘Allegedly’ because I haven’t been able to find a copy of it, other than what’s reported in the media (why does the mainstream media refuse to link to their sources?). But assuming it’s being correctly represented, it’s not good reading:

The culprit? Zero productivity growth for 20 years in Australia’s fastest growing sector, the non-market economy, along with business investment “stuck around 1990s recession levels for the past eight years, making workers less productive”.

Add to that new regulations that have stifled dynamism in other sectors, along with Australia’s high effective corporate tax rate (which I’ve written about before), and:

“Our work suggests that over many years of prosperity, first underpinned by hard-won reforms, and then by a terms-of-trade boom, we have developed a sense of complacency and largesse, and the broad movement of policy has been to sap rather than unleash productivity.

The golden goose that produced our fair and prosperous society is gasping for air.”

We could also grow more golden geese. According to a recent competitiveness report by Mario Draghi, a major reason why Europe doesn’t innovate is because they face “higher restructuring costs”. If a European firm takes a risk and fails, it could ruin them:

“Consider a simple example. Two large companies are considering whether to pursue a high risk innovation. The probability of success is estimated at one in five. Upon success they obtain profits of $100 million, and the investment costs $15 million.

One of the companies is in California, where if the innovation fails the restructuring costs $1 million. The other company is in Germany, where restructuring is 10x more expensive, it costs $10 million (a conservative estimate).

The expected value of this investment in California is a profit of $4.2 million. In Germany the expected value is a loss of $3 million.”

A major cause of those costs are labour rights. If European firms sack employees after an investment fails, they can be on the hook for more than three years of compensation.

The Albanese government has spent the past few years moving Australia’s labour market towards the European model. As Judo Bank’s Chief economist, Warren Hogan said:

“There is light at the end of the tunnel, we have advances in supercomputing and AI… but the key to it is being able to readjust our workforce, and the new IR laws are going to make our very restricted labour market even more restrictive. A rigid and highly regulated labour market is not going to work for the people of Australia or our economy.”

If Australia wants innovation and the economic complexity and resilience that comes with it, it’s going to need to move more towards the American model, which McKinsey concluded was significantly more conducive to growth:

“Everything from infrastructure through to tech, they say that the regulatory context at every level in the US is simpler and easy to navigate, more supportive of deploying capital than what is in Australia.”

I’ll only add that such a model is actually better for workers in the long-run: rigid labour rules raise unemployment and can restrict mobility, which is the best way for workers to get themselves a pay rise and helps to improve productivity.

For what it’s worth, not all of Europe has rigid labour markets. Denmark – the EU’s top innovator – " operates the famous ‘flexicurity’ model":

1. Employers can hire and fire at will.

2. Employees pay subscription fees to a government unemployment insurance fund and get up to two years’ benefits after losing their jobs.

3. The Danish government runs education and retraining programs.

Perhaps it’s worth noting here that without its innovative pharmaceutical sector, Denmark’s economy would have contracted by 0.1% last year instead of expanding by 1.8%.

Comments

Comments have been disabled and we're not sure if we'll ever turn them back on. If you have something you would like to contribute, please send Justin an email or hit up social media!