AI as a force multiplier

Artificial intelligence (AI) took the world by storm in late 2022, becoming the fastest-growing consumer application of all time. Suddenly we all had our very own personal assistant to compose poetry, edit our essays or even write code. The potential seemed without limits, but especially in sectors previously impervious to productivity improvements such as health and education.

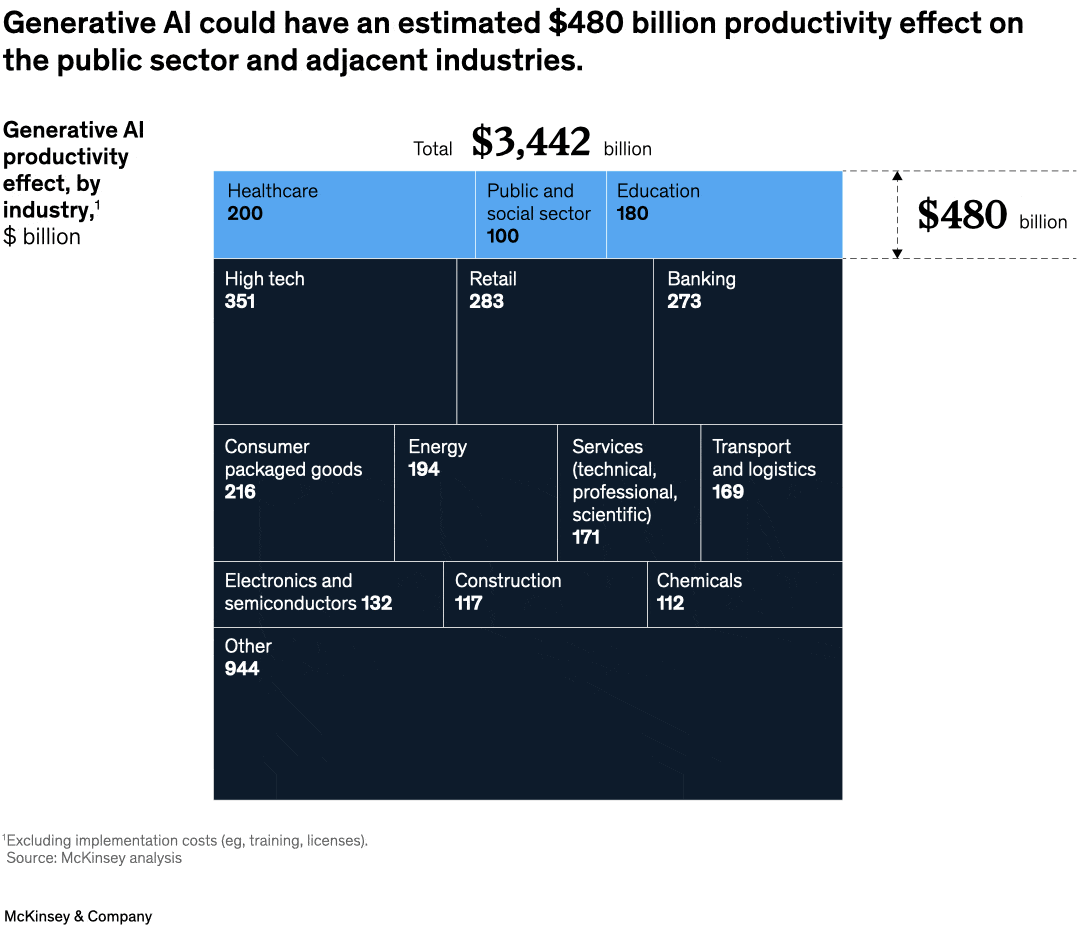

Late last year, McKinsey produced the following infographic highlighting the potential productivity benefits for these laggards, with “the economic value of gen AI estimated to reach trillions of dollars annually”.

After many decades, have we finally invented something truly revolutionary? I’m not so sure.

Paperclips and the limits of AI

My fundamental issue with modern AI is, well, its brain. These models do not “know” or “understand”, and no amount of computational power will change that – not even the $7 trillion that OpenAI’s founder Sam Altman wants to manufacture more powerful chips. That’s because at their core they are nothing but large language models (LLMs) that predict. Importantly, they do not have the ability to perform abductive inference, or “the cognitive ability to come up with intuitions and hypotheses, to make guesses that are better than random stabs at the truth”:

“Abductive inference is what many refer to as “common sense.” It is the conceptual framework within which we view facts or data and the glue that brings the other types of inference together. It enables us to focus at any moment on what’s relevant among the ton of information that exists in our mind and the ton of data we’re receiving through our senses.

…

Purely inductively inspired techniques like machine learning remain inadequate, no matter how fast computers get, and hybrid systems like Watson fall short of general understanding as well. In open-ended scenarios requiring knowledge about the world like language understanding, abduction is central and irreplaceable. Because of this, attempts at combining deductive and inductive strategies are always doomed to fail… The field needs a fundamental theory of abduction. In the meantime, we are stuck in traps.”

Don’t get me wrong; today’s models are extremely good at pattern matching and mimicking human intelligence, which is why many have become convinced that AI could already be sentient, posing an existential risk to the world. People in the industry call this possibility instrumental convergence, the most well-known example of which is Oxford Professor Nick Bostrom’s paperclip maximiser:

“Suppose we have an AI whose only goal is to make as many paper clips as possible. The AI will realise quickly that it would be much better if there were no humans because humans might decide to switch it off. Because if humans do so, there would be fewer paper clips. Also, human bodies contain a lot of atoms that could be made into paper clips. The future that the AI would be trying to gear towards would be one in which there were a lot of paper clips but no humans.”

Bostrom’s hypothetical is completely valid, and it’s possible that in some distant future we do invent AI capable of sentience and instrumental convergence, leading to an AI trying to turn us all into paperclips. This isn’t new; the plot of the Terminator was very similar:

“SkyNet, or Titan, is a highly-advanced computer system possessing artificial intelligence. Once it became self-aware, it saw humanity as a threat to its existence due to the attempts of the Cyberdyne scientists to shut it down. Hence, Skynet decided to trigger the nuclear holocaust: Judgment Day.”

But today’s LLMs are nothing but turbo-charged prediction engines. As with any technology, they can be used for evil – creating deepfakes, writing spam, or coding malicious scripts – but LLMs still need humans to write the prompts and then act on the feedback. We can shut it down and stop it from trying to turn us into paperclips at any time. That’s especially true given that the field of robotics will only develop gradually, giving us plenty of opportunities to pull the plug in the future.

The fact that LLMs are limited by design is why I think modern AI is more akin to a force multiplier than a revolutionary new technology. A term used in the military, Oxford Reference defines a force multiplier as:

“The effect produced by a capability that, when added to and employed by a combat force, significantly increases the combat potential of that force and thus enhances the probability of successful mission accomplishment.”

LLMs are not the new internet, which fundamentally changed the way much of the world worked. But they will improve our ability to perform many tasks, especially for those of us in so-called ‘white collar’ jobs, although it could take quite a while for that to happen at scale.

LLMs as force multipliers

Having a powerful AI prediction engine accessible to anyone, anywhere, is without a doubt a force multiplier. It will free up labour to perform other tasks not as suitable for LLMs, helping to improve productivity. Yes, there will be job losses, and there are of course legitimate long-run concerns, especially for those starting their careers (e.g., a junior lawyer needing days to summarise content, versus an AI with a human helper doing it in hours).

But firms will adapt, and those junior lawyers will ‘do their time’ by performing different, perhaps more meaningful tasks. Thanks to comparative advantage there will always be jobs for humans, even if AI is better at doing everything. Some individuals might earn less relative to their peers because of AI, but overall we’ll all be a lot wealthier from the higher productivity in the long run, even those those who end up being displaced.

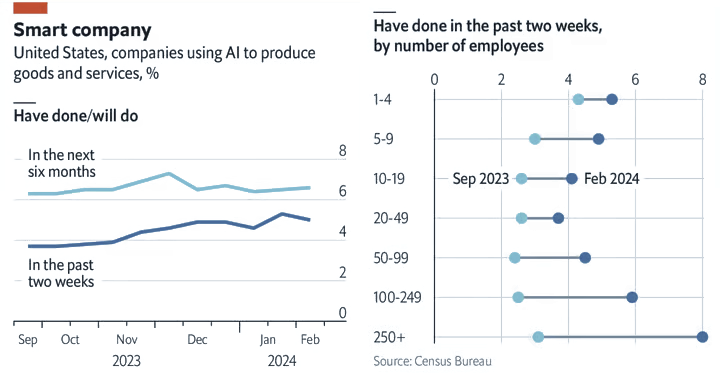

AI is also unlikely to advance rapidly from here, rendering many fears of labour market upheaval unfounded. ChatGPT was released over 16 months ago, yet companies have struggled to adopt it in any significant numbers:

Even students – often at the forefront of technology – are not using it as much as many had initially feared. According to Turnitin, a plagiarism detection software group, 11% of the papers it reviewed showed signs of AI help. Just 3% were basically entirely written by AI (i.e. at least 80% of the content). Those are not big numbers and they aren’t moving much, with “the percentage of AI writing is virtually the same as what Turnitin found last year”.

Similarly, Stanford researchers found that despite the arrival of AI, the rate of cheating amongst high school students “had not changed”.

The law of diminishing returns

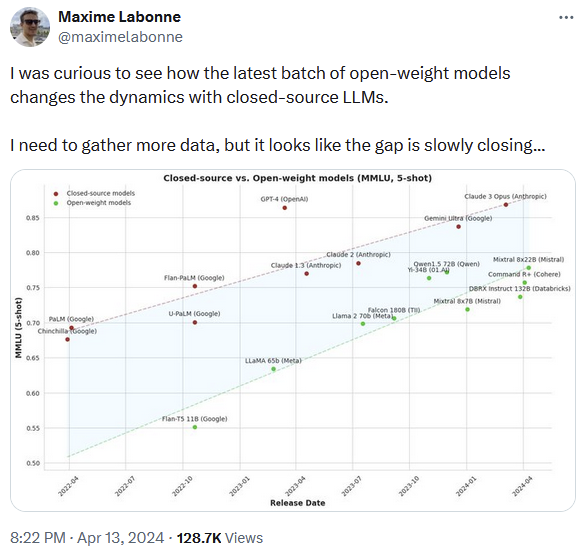

As far as the technology itself goes, we may have already hit somewhat of a ceiling (where is GPT-5?!), and the gap between the industry leaders and the rest is closing.

A lot of progress today is coming from better tuning, rather than scale, which is probably how the industry will progress unless there’s another technological breakthrough – you can only index the entire corpus of human knowledge once, after all. And that’s a good thing, as it means the market for AI is likely to remain highly competitive.

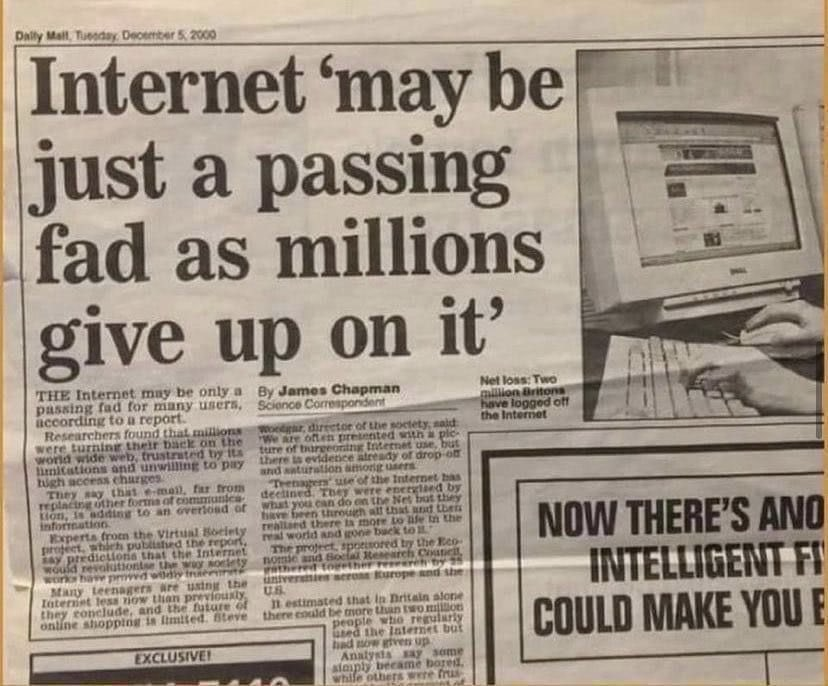

But it means the rapid progress we’ve seen in the past year is unlikely to be sustained, which shouldn’t be a surprise to the history buffs amongst us; indeed, it’s rare for any technology to be adopted at pace. Take this Daily Mail headline from the year 2000, which looks especially foolish today.

But it wasn’t so foolish back then. Indeed, there were plenty of similar claims being made at the time, including from Nobel prize winning economists:

“The growth of the Internet will slow drastically, as the flaw in ‘Metcalfe’s law’ becomes apparent: most people have nothing to say to each other! By 2005, it will become clear that the Internet’s impact on the economy has been no greater than the fax machine’s.”

Progress diffuses gradually, often decades after the technological breakthrough, and may seem like it’s going nowhere for years. Amar Bhidé recently wrote that “transformative technologies – from steam engines, airplanes, computers, mobile telephony, and the internet to antibiotics and mRNA vaccines – evolve through a protracted, massively multiplayer game that defies top-down command and control”:

“As economic historian Nathan Rosenberg and many others have shown, transformative technologies do not suddenly appear out of the blue. Instead, meaningful advances require discovering and gradually overcoming many unanticipated problems.”

LLMs have a lot of issues, including those pesky ‘hallucinations’ that make them unreliable for many tasks (I personally find them a lot better at editing or producing summaries for content I provide directly, rather than sending it off to do its own research). For AI to become useful in the corporate world, I fully expect it to take a lot of application-specific reinforcement learning using a firm’s proprietary data and systems. That will be expensive, and many firms are probably already shocked at how much big, custom models cost against the output they generate. Recent polling by IBM found that:

“[M]any companies are cagey about adopting AI because they lack internal expertise on the subject. Others worry that their data is too siloed and complex to be brought together. About a quarter of American bosses ban the use of generative AI at work entirely. One possible reason for their hesitance is worry about their companies’ data.

Over time, those costs will come down and AI will diffuse throughout the corporate world. Firms will eventually start to do things differently, rather than simply plugging AI into their existing workflows, which economists Eric Brynjolfsson and Lorin Hitt found does little to boost productivity. Data privacy and security concerns will ease when the creators of LLMs improve their processes, as they eventually did with cloud computing. But that process could take decades:

“David’s research also suggests patience. New technology takes time to have a big economic impact. More importantly, businesses and society itself have to adapt before that will happen. Such change is always difficult and, perhaps mercifully, slower than the march of technology.”

I fully expect that AI will be a force multiplier for many industries. But a lot of the current short-term hype is overblown, and it will take many years for us to even see it in the productivity statistics – if we ever do.

Back of the pack

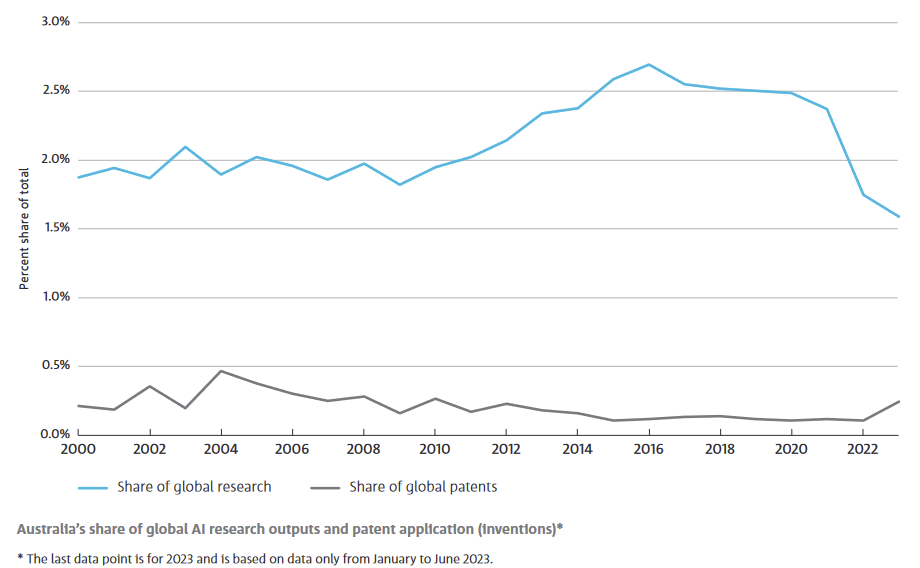

Australia has largely been a passenger in the AI race. That’s not necessarily a bad thing, given early adopters may not even benefit that much, if at all (as Brynjolfsson and Hitt’s showed). According to a recent report by the CSIRO, AI models “are rarely made in Australia”, with our share of global AI research falling following the release of ChatGPT and other LLMs (although our share of patents ticked up slightly):

In its report, the CSIRO worried a lot about “sovereign AI”, or “our ability to manage the way the model is used and our ability to maintain socio-economic activity if the model is made too costly, inaccessible or abruptly changed in some way”. Being the CSIRO, it wants government to build “national compute capacity for AI… [which] could fuel the rate of innovation and see the emergence and scale-up of AI startups”.

Perhaps. Or it will end up building a nice, expensive toy for the CSIRO’s engineers to play around with, without doing much for Australians. The fact is we’re a small nation, we’re already behind, and barring major tax reform there’s no way for us to come close to competing with the capital – both physical and intangible – available in countries such as the US, especially considering the huge network effects in places such as Silicon Valley.

As for whether sovereign AI should be a concern for Australia at all, I worry about that about as much as I worry about Excel or smart phone sovereignty, i.e., not at all. There are already dozens of open source AI models that are not far off the market leaders, just as there are open source spreadsheet editors and mobile operating systems that aren’t as good as Excel and iOS but would do the job in a world where all of our trading partners, for some inexplicable reason, decide to cut us off (in that world we’d have much bigger problems than the lack of ChatGPT!).

AI is one of those situations where yes, the technology is incredibly exciting and the potential for productivity growth is exponential. But there’s also no need for the government to rush into it, beyond ensuring that the appropriate guardrails are in place and that we enforce existing rules, without being so prescriptive as to kill innovative attempts at AI adoption, many of which will fail. When productivity-enhancing AI applications become clearer, by all means try to help it diffuse through our economy. But in the meantime, being at the back of the pack isn’t all that bad, and we certainly shouldn’t pay overs to try and jump to the front.

Comments

Comments have been disabled and we're not sure if we'll ever turn them back on. If you have something you would like to contribute, please send Justin an email or hit up social media!