Albo's HECS changes: fairer and cheaper, or regressive and expensive?

On Sunday, the federal government decided to “wipe” a few billion dollars’ worth of student debt from Australia’s Higher Education Contribution Scheme’s Higher Education Loan Program (HECS-HELP), in a plan Prime Minister Albanese said would make student loans “fairer and cheaper”.

Before getting into the nitty gritty of the changes, a bit of background is important to understand why this has happened. For those not familiar with Australia’s higher education system, HECS-HELP basically includes a subsidy for Australian students (we charge international and certain domestic students a lot more), as well as an optional loan if you can’t afford – or don’t want – to pay upfront. The name is a bit of a mouthful because since its creation in 1989 it has undergone a few reforms, so to avoid confusion I’m just going to call it HECS (its original name).

In normal times, HECS is relatively uncontroversial. That’s because HECS isn’t your normal loan; no credit checks are necessary, it’s interest free, and you don’t even have to repay the principal until you earn above a certain threshold, with the real value of the debt preserved through an annual indexation to consumer prices (CPI). In fact, it’s such a good deal that it almost always made financial sense to take a HECS loan, regardless of your socioeconomic status, because paying up front would cost you more in terms of the opportunity cost of that money – whether it be paying off other debts, saving for a house, or even building up a share portfolio. That present value calculation became even more one-sided after the government scrapped the up-front payment discount.

By comparison, a student in Ontario, Canada can get a student loan without credit checks but has to pay floating interest of the Prime Rate plus 1.0%, the total of which is currently 8.2%. And unlike HECS, Ontario’s loans have no income threshold: you only have six months after you graduate or leave full-time studies before you need to start repaying your loan. Ouch!

The pandemic changed the calculus

However, we’re no longer in normal times. The post-pandemic inflation caused the indexation of HECS last financial year to reach 7.1%, so for the first time in decades it made sense to pay off as much of it as possible before the 1 June indexation date. But many people either didn’t know, didn’t have the cash, or intended to pay it off but were caught out by a quirk in the scheme whereby indexation is set on 1 June each year and processed by the Australian Tax Office (ATO) on 1 July (i.e. in the new financial year). The indexation is only calculated on balances up to 31 May, so anyone who made a contribution after that date would have been indexed on debt they already repaid.

Now, technically, there’s nothing inherently wrong with this process; these lags also take place when the debt is first accrued, so while the ATO ‘gains’ by using 31 May for its calculation date, it ’loses’ at the start – a student commencing study in February won’t have any of their debt indexed for a full year after it was originally borrowed. Those lags persist throughout a student’s study as they accumulate more debt, so they’re actually ahead of inflation most of the time.

But the media and politicians don’t care about what’s technically right or wrong. I’ll let the Education Minister, Jason Clare, explain what the government has just done:

“The Universities Accord recommended indexing HELP loans to whatever is lower out of CPI and WPI.

We are doing this, and going further. We will backdate this reform to last year. This will wipe out what happened last year and make sure it never happens again.”

Essentially, the 7.1% increase on 1 June 2023 will be reduced to 3.2% (which is what the wage price index, or WPI, was that year) and this year’s upcoming increase will be reduced from 4.7% to an even 4%.

The change is great news if you’re a current or former student with a HECS debt and currently, or intend, to earn enough to make compulsory payments. Even if you did the smart thing and paid some of it off prior to the 31 May indexation cut-off last year, the government is going to ‘make you whole’.

But just because something is good for a group of people – in this case, over three million – doesn’t necessarily make it good policy. The government might claim that the debt has been “wiped”, but the money had to come from somewhere; there’s always a trade-off, and any good policymaker should want the returns on their decision to be higher than the next best use of those resources.

So, let’s take a look – is this decision a winner, a stinker, or a bit of both (politics and economics are often at odds)?

The economics of higher education

Governments all over the world subsidise higher education, whether directly (e.g. reduced tuition) or indirectly through some kind of student loan system. That’s in part because, to some extent, having an educated population is considered a public good:

“In other words, education has positive externalities whose value is not captured by the person who pays for the education. Because these externalities exist, the argument goes, people tend to act as ‘free riders,’ receiving the benefit provided by others without paying for it. Thus, fewer people are willing to provide education than would be willing without such spillovers because they are not rewarded for some of the output they produce. Therefore, according to most economists, education will be undersupplied.”

To an economist, education is not a pure public good – even for something as basic as reading, there are also large private gains – and there are of course diminishing returns to how much the public benefits from each additional level of educational attainment. For example, just because it makes sense for everyone to be able to read, doesn’t mean everyone should have a doctorate.

So while education might be undersupplied absent government intervention, it will still be supplied. The question is then how much should the government provide? Too much and you’re effectively subsidising people’s private gains at the expense of the public; too little and the ‘spillovers’ from an educated society are suboptimal.

Fortunately, we have a starting point. The government’s recent Universities Accord, “a 12-month review of Australia’s higher education system”, looked into this issue and concluded that it should spend more on improving access to higher education. That’s perhaps not surprising, given that every member of the panel – except for Macquarie CEO Shemara Wikramanayake (where she found the time to sit on this panel, I do not know) – is directly affiliated with our universities in some capacity. It would be like asking members of the Defence Force to conduct a review on whether we should improve funding for defence.

Incentives aside, the Accord still had some good ideas, such as improving income support and “limit[ing] disincentives to do additional work”. Did you know that students on Austudy, our financial support program for students and apprentices with minimal assets, face effective tax rates of 50% on every dollar they earn over $255/week? Well, they do, and if you actually wanted to help the disadvantaged then that might be a better place to start than HECS.

Politics trumps economics

But as is often the case when a review provides the government with a shopping list of recommendations, many are ignored or misinterpreted. In this case, the government took the advice to “ensure that people’s HECS loans do not grow faster than wages”, and then expanded upon it.

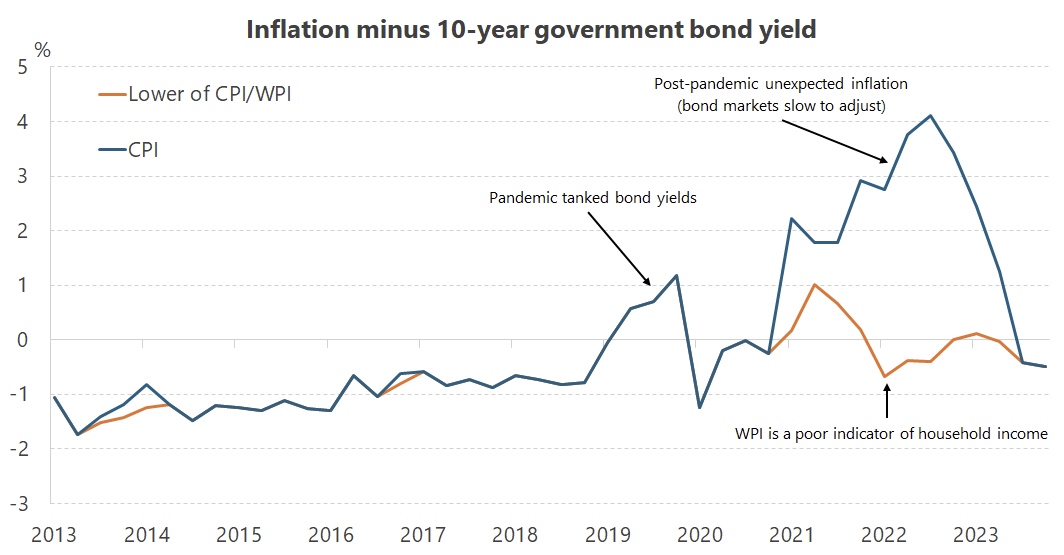

In effect, by changing the indexation to the lower of inflation or wages, it guaranteed that HECS loans will almost always lose their real value over time, mostly because the WPI is not a good indicator of household incomes and the CPI tends to overstate inflation (it’s not great at accounting for substitution).

The following chart shows whatever is lower out of the CPI and WPI against a proxy for the risk-free rate of return, for which I’ve used the 10-year Australian government bond. When it’s negative, the government is basically paying people to borrow, distorting the incentives between working and saving, or studying.

Now, it might make sense to lock-in a permanent subsidy for student loans if higher education were a pure public good, or that HECS removed a critical barrier to higher education for disadvantaged groups. But both of those claims are far from clear.

When did Labor become so regressive?

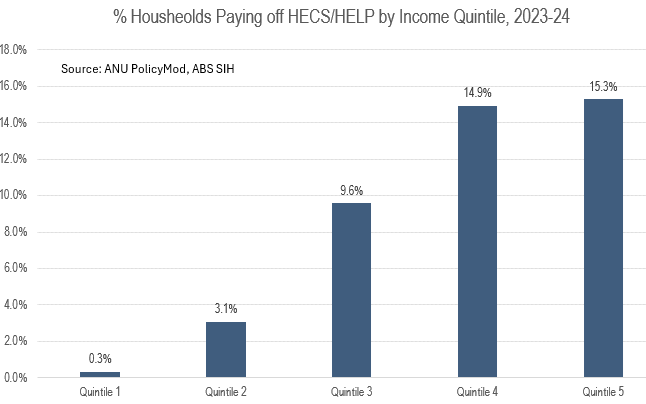

No matter how you cut it, the Albanese government’s change to HECS is regressive, in more ways than one. First, by design the people who are paying back HECS debt are disproportionately in the middle- to upper-ends of household income, because compulsory repayments are linked to income. Given that link, a HECS loan is a lot like a tax. So by reducing the cost of HECS debt, the government is reducing the progressiveness of it – it’s like a tax cut for the well-educated who also earn a decent living.

In addition, the HECS ’trap’ I mentioned earlier, in which people continue to be indexed on payments made after 31 May, only affected higher income households (as per the chart above, people on lower incomes do not make significant payments). By promising to make them whole, the government is committing to make a transfer to relatively high-income households.

Second, the changes to HECS indexation will disproportionately benefit people who, over their lifetimes, will earn middle- to upper-levels of income. According to Deloitte Access Economics, in Australia:

“For the average bachelor level student, their lifetime net private market benefits in the form of additional lifetime post-tax earnings is expected to be $142,000 in NPV terms ($674,000 when undiscounted). Relative to other workers, this represents a discounted earnings premium of 31% (37% undiscounted) associated with the average bachelor level qualification over an individual’s lifetime.”

Once your bachelor’s degree is done the gains don’t stop there: Gong and Pan ( 2023) found that a fourth (i.e. honours) year of university education increased earnings by “about 12% six months after graduation and persists at least four years after graduation”.

As the great Armen Alchian once asked, does it make any sense “to think that smart people should be given wealth at the expense of the less smart”? The government is making obtaining a bachelor’s degree cheaper for everyone – not just the marginal, disadvantaged student – including all of those future high-income individuals who would have gone to university anyway. While there’s certainly an argument for some level of government support to account for the public spillovers I mentioned earlier, the HECS scheme is already very generous.

Ignoring the actual issues

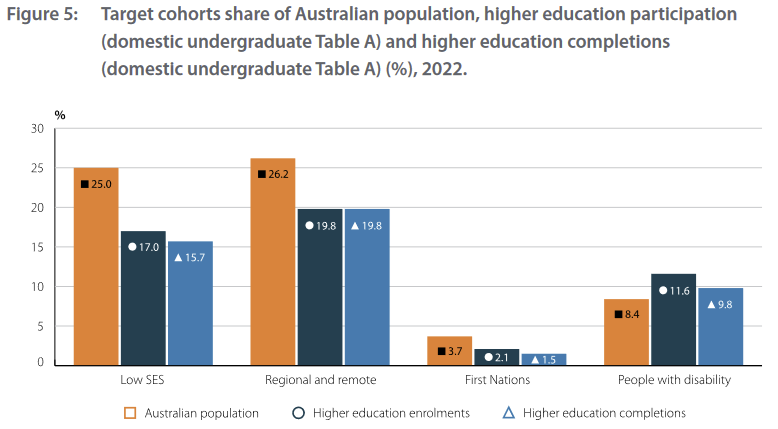

Third and finally, the Accord provided an interesting chart showing that low socioeconomic and other traditionally disadvantaged groups remain underrepresented in higher education.

The cost of HECS debt is not a barrier to higher education for most of the people in these groups, given that no payments are required to be made until you earn above a certain income threshold. The Accord noted that the main reason most people in the lowest socioeconomic quartile avoid commencing university, or drop out, is because of immediate “financial difficulty”:

“In 2015, students from the lowest SES quartile were 13 percentage points more likely to report financial difficulties as a barrier to undertaking further study than students from the highest SES quartile.”

If the government wanted to support higher education in a progressive rather than regressive manner, then those groups need to be targeted directly, for example through changes to Austudy. Instead, by making HECS loans more generous we are effectively using additional taxes collected from everyone – including from those in the bottom income quartiles – " on a service that benefits only a subset of citizens—a subset that is primarily made up of middle and upper income people".

So to answer my question from earlier, all in all this policy is a bit of a regressive stinker, especially for a Labor party that claims to be operating with a “framework to establish a long-term progressive Labor Government” [emphasis mine]. While relatively small in scale, it still increases the transfer from those without a university education to those with one, all while failing to address the people facing actual hardships and barriers.

But if we drop the assumption that our politicians have utilitarian motives, this policy makes perfect sense – in a budget with payments of over half a trillion dollars, what’s a few extra bil on a feel-good change that will likely appease the median voter and potentially steal some progressive, inner city votes away from the Greens, right?

Comments

Comments have been disabled and we're not sure if we'll ever turn them back on. If you have something you would like to contribute, please send Justin an email or hit up social media!