An independent RBA is better than the alternative

Tomorrow is Budget day. I’m not going to do a Budget post because most of the major policy decisions have already been announced or deliberately leaked, and I don’t think there’s much value to add there.

But what I do want to dive into is whether or not the government has done anything to resolve the problem of structural fiscal deficits of around 2% of GDP, and what the Budget might mean for inflation and the future of the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA). In terms of the former, probably the best indicator from Treasurer Jim Chalmers is this speech from last week:

“The primary focus in the Budget is on inflation in the near term and then growth in the medium term. It will be an inflation‑fighting and future‑making budget. It will be a budget suited to the cross currents and the conditions that we confront.

There will be cost‑of‑living help for people doing it tough, there will be key investments in a Future Made in Australia and all of that will be underpinned by the responsible economic management which has been a hallmark of this Albanese government.”

So, handouts in the short-run, big spending on industrial policy in the medium-run. There are a few problems with that, starting with the fact that the federal government, along with every state government, is running a headline fiscal deficit. That is, they’re borrowing to cover operating activities and net “investment” in assets for policy purposes. The latter is an important distinction, because it’s excluded from the more commonly used underlying balance (which is what the Treasurer will cite). It’s how some of our governments are getting away with having their cake and eating it too: claiming to be running a surplus, all while increasing net debt that future generations will have to pay off.

I don’t expect that to change tomorrow. According to calculations by former Treasury official Steven Hamilton, Chalmers’ government has already injected “almost 1 per cent of GDP… the equivalent of two interest rate cuts” in net discretionary policy spending in the current financial year. And that excludes the impact of the stage three income tax cuts and National Disability Insurance Scheme cost blowouts, the latter of which has been farcical in terms of just how many people have been taking the piss.

So, unless Chalmers is cutting spending tomorrow – which, in combination with collecting more taxes, is the only way to credibly reduce structural deficits – his Budget will be making inflation worse in the “front end”. He can use accounting gimmickry to publish Budget forecasts showing “inflation falling faster than the Reserve Bank has suggested” until the cows come home, but no amount of ‘cost of living support’, also known as handouts or subsidies, will reduce inflation. They might temporarily reduce measured inflation for a given good or service, but they will increase actual inflation because they add to aggregate demand and reduce confidence that the government will pay back the entirety of the deficit in the future (as opposed to inflating some of it away).

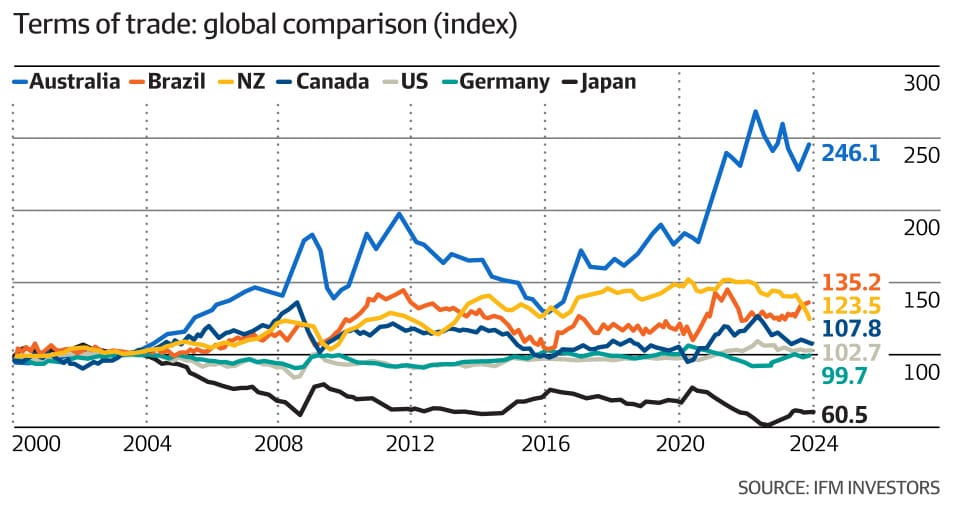

By not banking a headline surplus, Chalmers is doing precisely the opposite of what is needed to help get inflation back down. And he has no excuse: last week, the AFR included the following chart showing just how fortunate Australian Treasurers have been since the mid-2000s. No one has had better luck than Jim Chalmers:

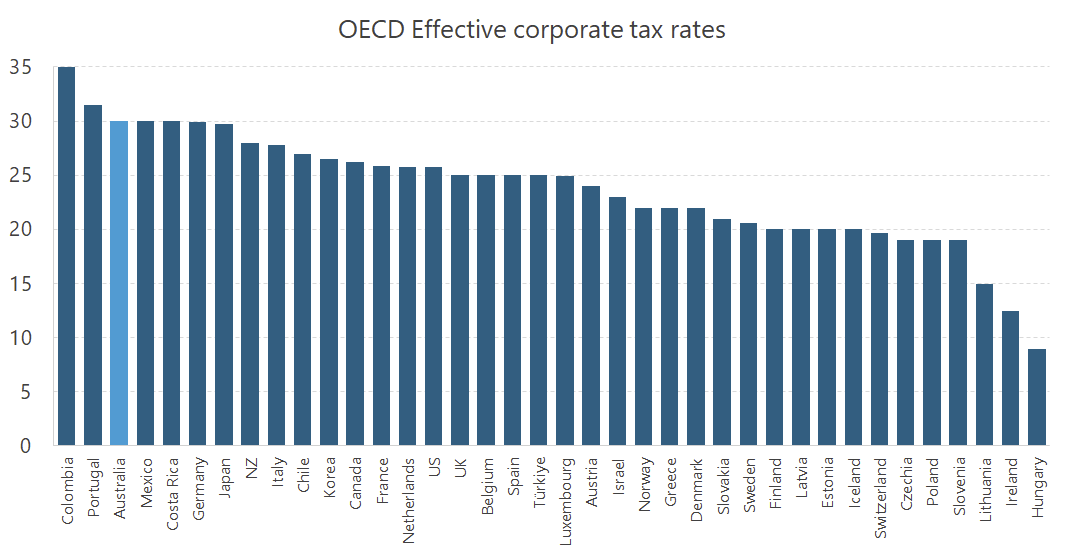

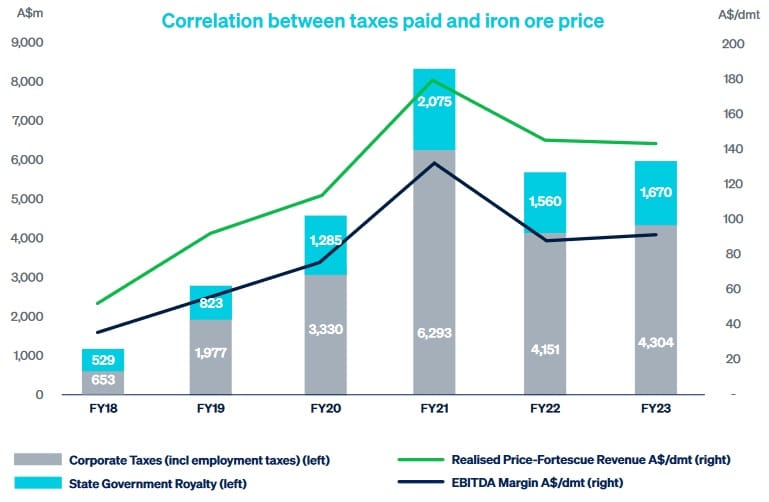

When the terms of trade rises, which means the price we get for our exports increases faster than what we pay for imports, many governments – but especially the Commonwealth – enjoy ‘free’ revenue, due to our world-leading 30% corporate tax rate. Mining companies can deduct expenses from their corporate tax obligations, but when prices reach a certain level those deductions are exhausted and it becomes close to a pure 30% tax on mining revenue, as shown in Fortescue’s Sustainability Report.

Iron ore is our biggest export, and prices have been high throughout Chalmers’ term. Combine that with soaring coal prices and record tax receipts courtesy of bracket creep, and from a windfall revenue point of view, he’s Australia’s luckiest Treasurer since Wayne Swan.

Pressure on the central bank

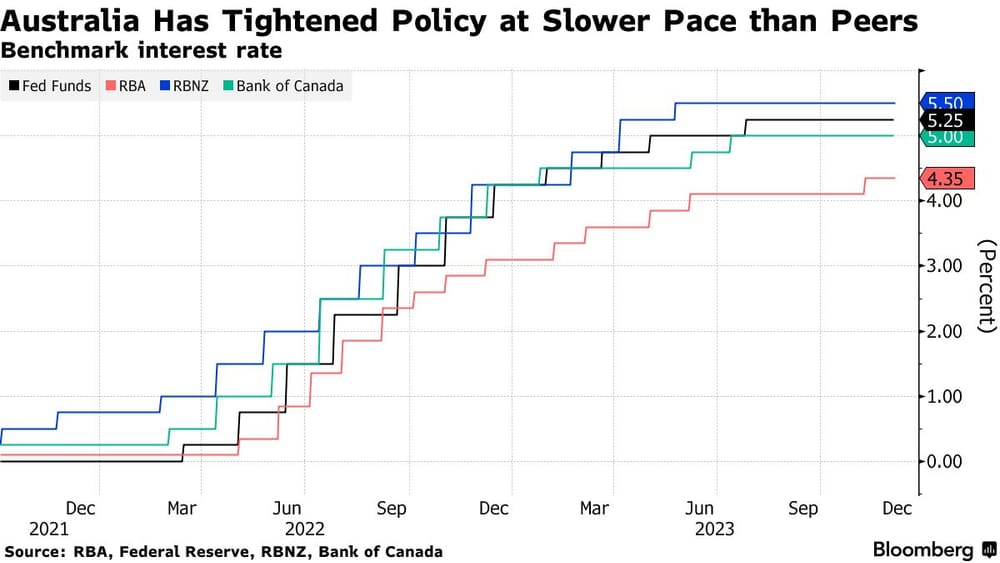

Perhaps the biggest consequence of not exercising fiscal restraint is the pressure it will heap on the RBA, which has been quite dovish when compared to its global peers.

But what really concerns me is that the pressure won’t just be economic – i.e. to raise rates due to persistent inflation – but political. This government has already demonstrated a rather blasé attitude towards existing institutions, such as thinking it can predict future champions of industry despite the success we’ve had with a policy of comparative advantage; it’s not a huge leap to think that it also believes it can know what the appropriate tightness of monetary policy should be.

Already, there are suspicions that Chalmers has ulterior motives in his desire to rush through reforms to the RBA. Those suspicions stem from his power of appointment: having added two former union officials, Elana Rubin and Iain Ross, to the RBA board last year, Chalmers now wants to be able to decide which existing members – if any – will move from the existing monetary policy board to a new, “less-influential” governance board.

Remember that Chalmers also appointed governor Michelle Bullock last year, who chairs the monetary board. As part of the RBA reforms, the Treasury Secretary – also a Chalmers appointee – is guaranteed a seat on that same board. Add it all up, and Chalmers is effectively asking for the power to appoint every single member of the RBA’s interest rate-setting board.

Now, I don’t want to suggest that Bullock, or any future appointee, are political operatives for Chalmers. Just that it could be a possibility, and the fact it’s a possibility does undermine the independence of the RBA; those familiar with European history will know that gaining control of the voting Politburo by influencing the appointment process was how Stalin came to power in the former Soviet Union.

While the RBA is not the Soviet Politburo, the stakes are still high. According to the IMF, increased political influence over central banks is a very real threat that has been bubbling up in recent months, and not just in Australia:

“Central bankers today face many challenges to their independence. Calls are growing for interest-rate cuts, even if premature, and are likely to intensify as half the world’s population votes this year. Risks of political interference in banks’ decision making and personnel appointments are rising. Governments and central bankers must resist these pressures.

…

The recent success in bringing down inflation contrasts sharply to the economic instability that prevailed during the high inflation period of the 1970s. Back then, central banks didn’t have clear mandates to prioritize price stability, or clear laws protecting their autonomy. As a result, they were often pressured by politicians to lower interest rates when inflation was high.

Everyone was hurt by this high inflation, boom and bust era—especially people living on fixed incomes who saw their real incomes and savings eroded. Success in reducing inflation only came in the mid-1980s when central banks were given political support to aggressively fight inflation.”

Regular readers know that I’m no fanboy of the RBA; under the stewardship of Philip Lowe, it ignored a mountain of evidence that inflation was not going to be transitory and persisted with its ultra-easy monetary policy for far too long. It was a classic case of group-think: well, every other central banker I spoke to at Davos thinks this too; who am I to question my priors?

And it led to costly mistakes:

“The forecasting errors since the surge in inflation in 2021 have been very large. Prior to the pandemic, only 10% of forecast errors had been greater than +1%. But including the recent episode, 10% of forecast errors have now been larger than 1.5%. Ten of the 14 largest (positive) forecasting errors at a 18 month horizon have occurred since 2021.”

The checks on executive discretion within the RBA were, and still are, weak: in at least the past decade, not a single board member voted against the RBA executive. In the end, too much discretion for unelected bureaucrats ended up costing us – that is, Australian taxpayers – at least $50 billion, or more than $5,500 per household. And that doesn’t even include the perhaps much larger cost of the inflation.

Don’t fall for the nirvana fallacy

None of that means I’m against an independent RBA. Sure, a first-best option would be something resembling sound money. But I don’t think that’s realistic when the political winds are blowing in the opposite direction, so the next-best alternative is preserving an independent RBA. Sometimes no change is the best kind of change; we should never forget the nirvana fallacy, best articulated by Harold Demsetz in 1969:

“The view that now pervades much public policy economics implicitly presents the relevant choice as between an ideal norm and an existing “imperfect” institutional arrangement. This nirvana approach differs considerably from a comparative institution approach in which the relevant choice is between alternative real institutional arrangements.”

There is no evidence that a more politicised RBA would have done any better at handling the pandemic than what we had in place at the time, nor that it would do any better in the future. In fact, it probably would have done much worse: history shows what happens when politicians interfere with monetary policy.

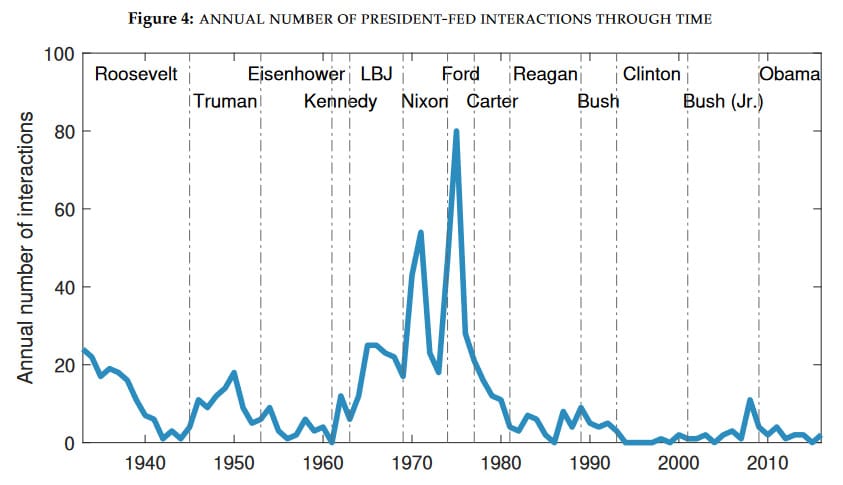

The more a US President meets with the central bank, the worse inflation becomes:

“I find that political pressure shocks increase inflation strongly and persistently. My procedure can quantify this effect: increasing political pressure 50% as much as Nixon for six months increases the U.S. price level by 8%. While the benefits of central bank independence have largely been highlighted using cross-country data, my results demonstrate them using evidence from within one economy through time.”

It’s not hard to understand why. Politicians want expansionary monetary policy so that they can spend more, boosting their re-election odds. We all lose in the long-run, but in the short-run the stakes are high for a politician: it could be the difference between another term in government or having to get a real job!

Now, that doesn’t mean politicians can’t have a role in monetary policy. They have an important part to play in determining what guardrails are in place, preventing the RBA from doing undesirable things like mission creep, or using excessive discretion as Philip Lowe looks to have done during the pandemic. Central bank discretion, after all, has a relatively chequered record, and we could probably do with more rules:

“Placing boundaries around monetary policy is hardly a new idea. Since the Fed’s founding, economists have proposed different means to bring greater discipline to the policy process, but with little success. In the early 1960s, for example, Milton Friedman proposed that the growth rate of the money supply be set at a constant rate of growth, k-percent rule, to achieve money and economic stability. John Taylor proposed a relatively simple formula that sets the fed funds rate to balance the trade-off between economic growth and inflation. Ben McCullum proposed to guide Fed policy by targeting the growth rate of nominal GDP. While different in mechanics, the goal of each proposal is to develop monetary policy within a more consistent policy framework.”

A few months ago MIT economist Athanasios Orphanides wrote a paper that showed the US Fed already follows something akin to “a simple natural growth targeting rule that prescribes that the federal funds rate during each quarter be raised (cut) when projected nominal income growth exceeds (falls short) of the economy’s natural growth rate”.

In fact, he found that the only time since the early 1990s that it deviated from that rule was during and after the pandemic, leading to the inflation we’re all now ’enjoying’ (many other central banks, including the RBA, made similar errors).

Unfortunately, last year’s Review of the RBA did not even consider alternatives to complete bureaucratic discretion. That discretion raises the stakes for politicians to exert control over those bureaucrats (including their appointments), when what we should be pushing for is a boring, low-stakes RBA that quietly goes about its job of promoting price stability.

Politicians would still have control; if the RBA had to follow rules, it would have to come to Parliament asking for changes and be held accountable for them. By contrast, the current discretionary model – which the RBA reforms do not address – allows both the central bankers and the politicians trying to influence them to operate largely in the shadows.

To get on top of the current inflation and prevent it happening again, the last thing we want is a more politicised central bank. But given his actions to date, I worry that’s exactly where Chalmers is taking us.

Comments

Comments have been disabled and we're not sure if we'll ever turn them back on. If you have something you would like to contribute, please send Justin an email or hit up social media!