Are we the complacent country?

I spent most of Sunday looking for places to stay in Japan for a stopover on the way to Canada at the end of this year. I know, first world problems, right? But it did get me thinking about a recent OpEd by Chris Joye that I read recently, in which he warned that:

“As the government crowds out more of our day-to-day lives, we inevitably become entitled and complacent. This is evident in Australia’s poor productivity performance. Specifically, total ‘multifactor’ productivity has not increased at all in the past 25 years. … All of this informs this column’s apprehension that Australia could become akin to Asia’s Ibiza over the next two to three decades. A beach resort for well-heeled members of the Indo-Pacific that trades off tourism and natural amenities rather than any intellectual edge. It certainly satisfies the popular stereotype of bronzed brawn being our primary competitive advantage.”

I think that’s clearly an exaggeration: Ibiza’s population is around 160,000, or about the same as Darwin. It’s also located in Europe within cooee of many wealthy, developed countries, and the roughly three million tourists that visit each year account for something like 85% of its GDP.

To put that into context, Australia—with its 27 million people—would need to bring in over 500 million equally-wealthy tourists each year to replicate Ibiza’s tourism-driven economy. That seems unlikely.

Still, the Australian economy could certainly move further in that direction. Joye is essentially making an assumption that Indo-Pacific growth will surpass Australia’s by a considerable margin over the next two to three decades, such that current tourism flows reverse—i.e. regional purchasing power will move from Australian consumers to those elsewhere in the Info-Pacific.

And that’s where my recent experience booking places to stay in Japan comes into it.

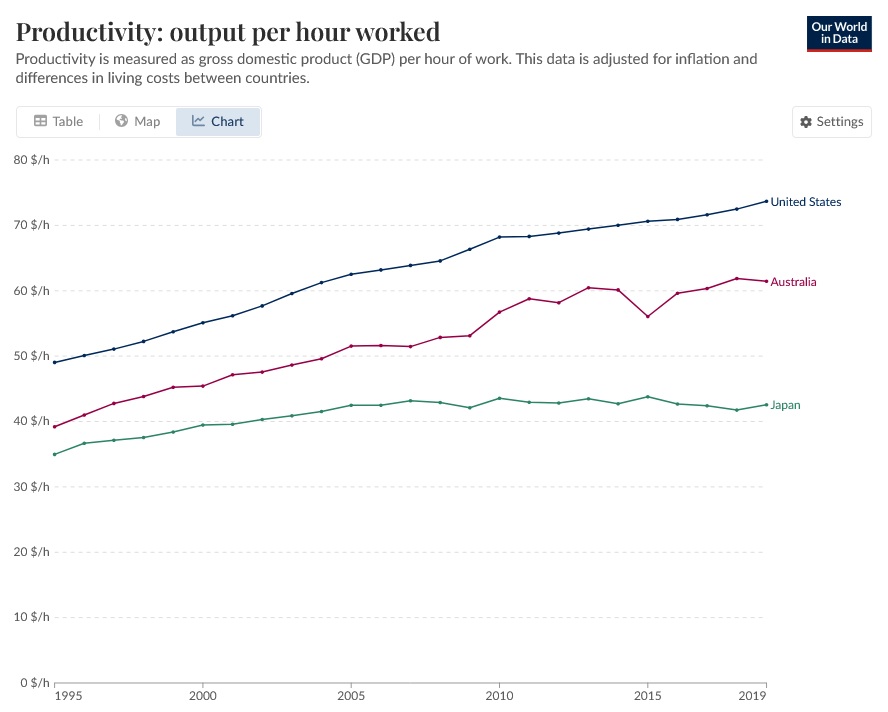

The gap between productivity in Japan and that of Australia and the US has grown considerably larger since the mid-1990s. To me, that makes Japan a more realistic vision into what a poorer, older, future Australia might look like—if we don’t get our act together.

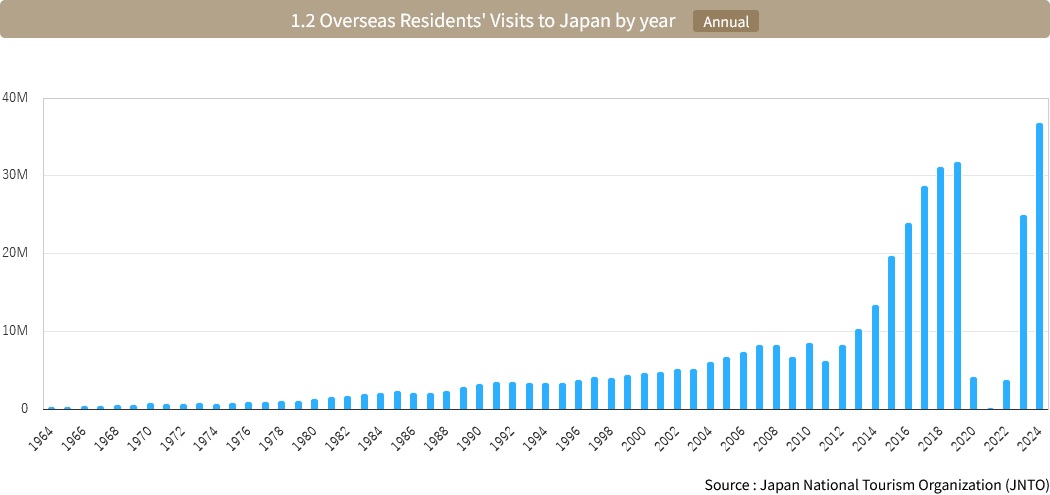

Tourism now makes up 7.5% of Japan’s GDP, versus around 3% in Australia. And unlike Australia where that economic share has been more or less flat for twenty years, the tourism share in Japan has increased by nearly 300% over the same period. Just take a look at visitor numbers:

Japan has had to gear its economy towards tourism out of necessity—to support an aging population, mountains of public debt, and zero long-run productivity growth. Its government wants to welcome 60 million inbound tourists by 2030, up from the record-high 36.87 million in 2024, which has been “a significant driver of much-needed growth in an economy that probably contracted last year”.

So, I think Joye’s warning was fair, even if his Ibiza analogy was far-fetched: if other Indo-Pacific nations close the productivity gap with Australia, then in twenty or thirty years our government is likely to go the way of Japan’s and pivot hard into tourism.

Reform is hard and can be politically costly, but what politician doesn’t love a bit of industrial policy?

But that’s also a big IF. For all of Australia’s problems—and Joye was right to warn that “rampant” government spending isn’t helping matters—I’m still confident that Australia’s relatively robust institutions will see us remain wealthier than almost all Indo-Pacific nations over the next thirty years.

I also take issue with Joye’s claim that the US, which has consistently put the rest of the world to shame in terms of productivity growth, has “recently” seen “a shift towards economic rationalism”. I can think of many more appropriate words to describe Donald Trump’s economic policies to date, but let’s just say they’re not appropriate to publish on these pages.

Indeed, if you’re looking for a way to improve Australia’s productivity growth, the “recent” economic shifts in the US are the last place I would cast my gaze.

Comments

Comments have been disabled and we're not sure if we'll ever turn them back on. If you have something you would like to contribute, please send Justin an email or hit up social media!