Are you a supervillain?

The US and China struck a trade deal last night. Essentially, US tariffs on China will be cut to 30%, and China’s on the US to 10%—for at least another 90 days, anyway. China will also remove non-tariff barriers on things like rare earths, and both countries agreed to establish some kind of trade consultation mechanism.

Treasury secretary Scott Bessent said “We are in agreement that neither side wants to decouple.” Global equities surged, with the S&P500 closing up just over 3% for the day.

Yale’s budget lab has crunched the numbers, and even after this “deal” the average tariff rate in the US will be 17.8%—the highest since 1934—and will cost the average family around $2,800 per year, which will disproportionately affect lower income households.

But hey—a deal’s a deal, right? Yes, the state of global trade is still much worse than it was before Trump/Biden/Trump, but at least there’s no longer an effective embargo between the world’s two largest economies. As I wrote last week, the US looks set to be a high tariff country for the foreseeable future, and the best case scenario is some kind of deal—or “consultation mechanism”—that at least removes a bit of the considerable policy uncertainty Trump has caused, which can be more damaging than tariffs themselves due to its paralysing effect on investment.

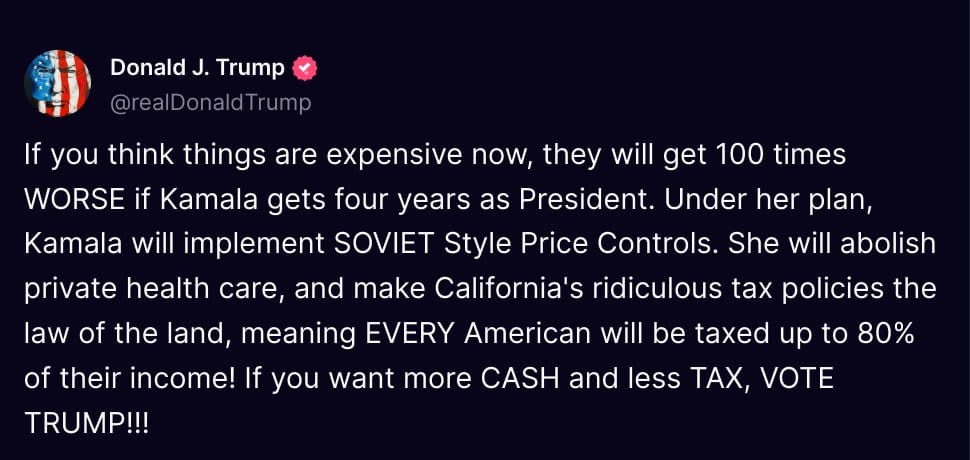

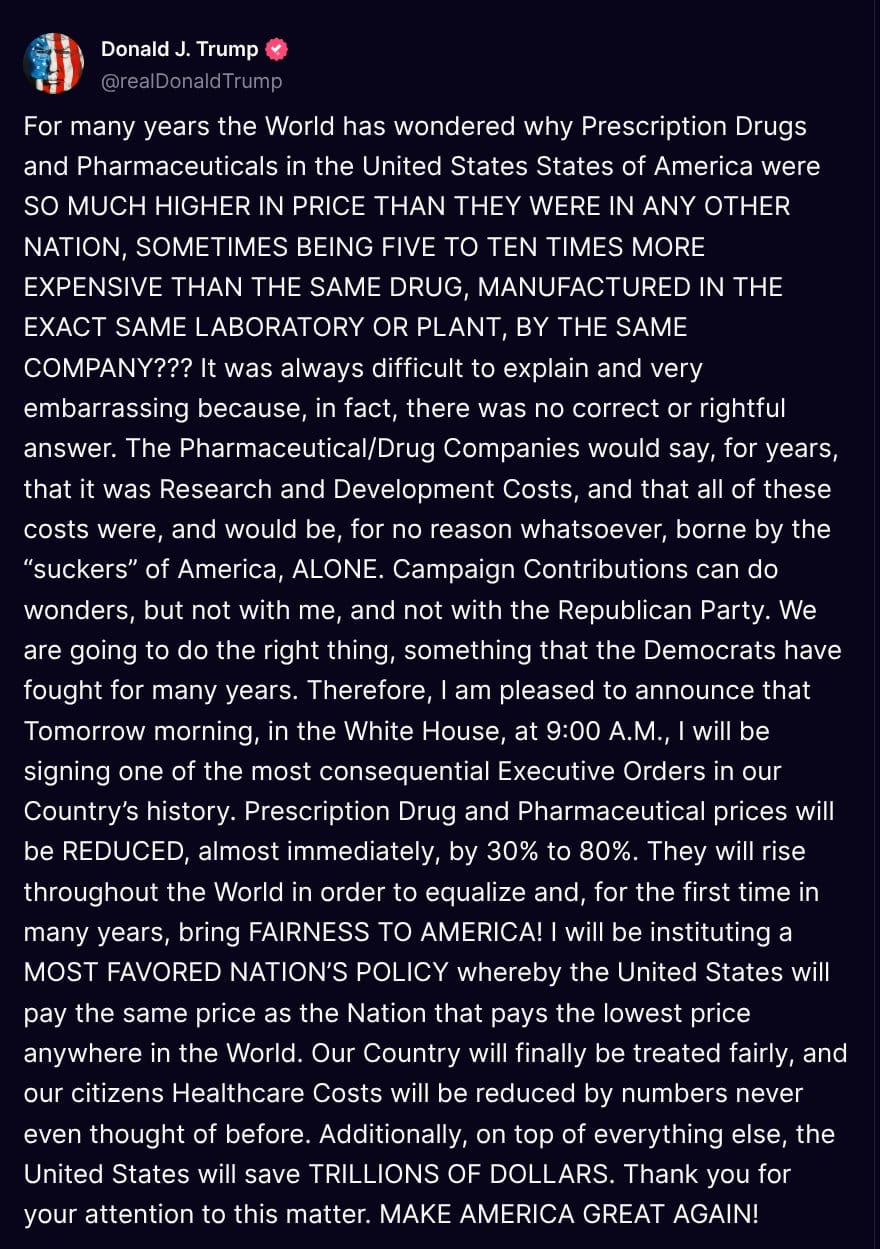

Now, amidst all the trade deal excitement you might have missed a fresh executive order signed by US President Donald Trump on pharmaceutical prices. Specifically, Trump intends to invoke what is effectively Soviet-style price controls on pharmaceutical medicines—the very tool he warned Kamala Harris would use before last year’s election:

Regular readers know how I feel about price controls. Whatever the perceived problem may be, price controls are never the answer:

“Prices are useful signals that help coordinate responses to changes in economic conditions. They convey information that creates an incentive for market actors to respond in socially beneficial ways.”

In the context of pharmaceutical medicines, price controls—Trump’s “most favoured nation’s” justification is but a veneer hiding what they really are—will dull the incentive to invest in R&D. Given that medicines are excellent at saving lives, after a period of time price controls means more people will die than would have absent said controls. Indeed, last year economist Tyler Cowen even wrote that people who support pharmaceutical price controls are literal supervillains, because their policy—whether through ignorance or malice—would lead to “millions of premature deaths”.

However, Trump does have a point—Americans do pay more than everyone else for brand-name ‘frontier’ medicines (but considerably less for unbranded generics). Part of that is because they buy so many more drugs than other countries, but it’s also because wealthy countries, including Australia, effectively free-ride on American consumers—we’re able to enjoy low brand-name prescription drug prices through the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS), which sees our government negotiate with foreign drug companies on behalf of all Australians. It’s basically a non-tariff barrier, given that the government is a monopsony (single) buyer and so has market power over American drug companies (we actually pay more than Americans for many over-the-counter medicines because of rent-seeking by the Pharmacy Guild of Australia).

But without US consumers paying more for ‘frontier’ medicines than people in other rich countries, innovation would slow and lives would be lost—including in Australia. In the economics profession it’s called a “market failure central to pharmaceutical innovation”:

“Firms developing novel products create public goods in the form of the scientific knowledge necessary to treat a medical condition. After such knowledge is developed, it is often a relatively trivial matter for another firm to replicate the product at a meaningfully lower fixed cost and drive down the financial return for the original innovator.

Therefore, absent some form of intellectual property protection, few rational firms would be willing to make the investments essential to product innovation. This is particularly true in markets, such as pharmaceuticals, where the costs of development are quite large, risks of failure are meaningful, intended payoff periods are long, and the costs of imitation are low. To address this concern, the current system involves governments providing intellectual property protection for limited time periods, so that innovative firms can sell their products at a higher price without the threat of direct competition.”

The unique quirks of the pharmaceutical medicine market are why organisations like the America First Policy Institute recommended that the US government should be “pressuring wealthy countries to end freeloading practices”, rather than cutting the higher US domestic brand name prices that enable pharmaceutical companies to “invest billions of dollars to develop new medicines”.

I don’t know what such “pressure” might look like; perhaps some kind of global treaty that determines how to pay for medicine R&D, linked to a nation’s ability to pay and the benefits they expect to receive (e.g. incomes and demographics).

But what I do know is that Trump’s solution is wide of the mark and will cause global net harm through the unintended consequences it unleashes.

For example, Yale economics professor Jason Abaluck noted that as a result of Trump’s executive order, “prices will probably increase in low-income countries and people in the US won’t save 50-80% as you might naively project if you didn’t understand that prices are determined in equilibrium”:

“If it’s better for prices to be higher, does this mean this policy is good? No, because the policy will still lower pharma revenue in total (it forces them to price above the profit maximising level in other countries), meaning they also have diminished incentives to innovate!

In other words, this is a bad policy that would only be pursued by people who hadn’t thought through the consequences that probably harms everyone for no reason.”

Kristian Stout of the International Center for Law & Economics warned that Trump risks turning the US into Europe:

“Europe once led the world in pharmaceutical innovation, introducing twice as many new drugs as the United States during the 1970s. But the implementation of stringent price controls across European markets steadily eroded returns on pharmaceutical innovation, subsequently shifting industry leadership to the United States. Today, nearly half of all global pharmaceutical innovation is American in origin, while Europe’s contribution has dramatically decreased.

…

The disproportionate share of global pharmaceutical revenue earned in the United States is not simply a function of market size, but is also directly tied to the absence of the stringent price controls that characterise foreign markets. Introducing foreign price controls domestically would risk replicating Europe’s historical experience, where similar policies drastically reduced pharmaceutical innovation.”

There will be consequences for Australia, too. Anthony Albanese and Peter Dutton both pledged not to touch Australia’s PBS during the election campaign. Fair enough; cheap medicines are popular with voters, and given the context of the election it would have been political suicide if you were perceived to be siding with Trump on this issue.

But it’s not outside the realm of possibilities that pharmaceutical prices are used as a future negotiating tool. Yes, I’m aware of the contradictions, including that any treaty wouldn’t result in drug prices coming down for Americans. But hypothetically, let’s just say that Trump is playing 4D chess here and the end goal is a global drug treaty—perhaps even in exchange for reduced tariff rates and/or greater access for Australian companies to sell into the large US market.

Well, if push comes to shove and the choices are between working towards a treaty where everyone pays a bit more for medicines and resolves the market failure, or the US goes ahead with price controls linked to countries like Australia that have been exploiting monopsony power to effectively free ride on the US, wiping out billions in global medicine R&D and cost millions of life-years over time (especially in poor countries but also in Australia!), then I know what option I would choose.

But does Anthony Albanese?

Comments

Comments have been disabled and we're not sure if we'll ever turn them back on. If you have something you would like to contribute, please send Justin an email or hit up social media!