Australia's demographic dilemma

Given the way the political winds are blowing, a migration slowdown looks to be an inevitability in Australia. That’s largely because our political duopoly doesn’t tend to stray too far from the views of the median voter, and those voters turn against migration in times of turmoil:

“Historical data shows that concerns about immigration levels can ‘spike’ during periods of economic instability—and the Treasurer has warned that there are tough times ahead for Australia. But will this minority opinion matter in the contemporary Australian context?”

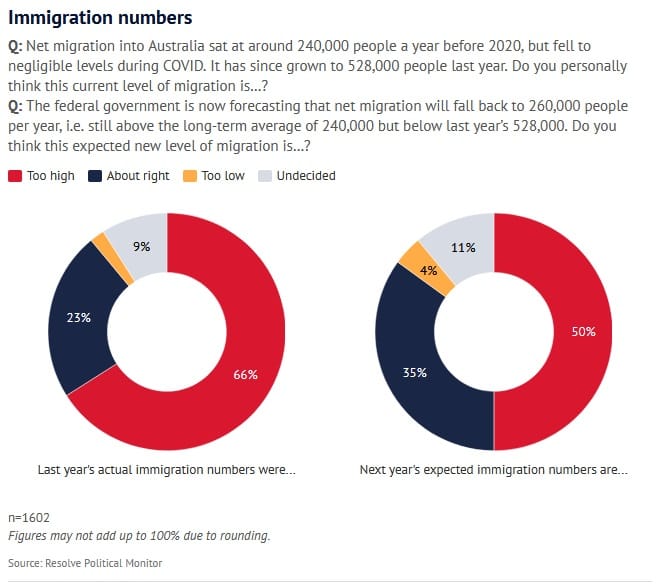

That was written in 2022, just prior to the most recent migration backlash. A survey published the other week by Resolve Strategic found that the median voter probably thinks even a migration level around the long-term annual average is now too high.

A key reason people claim to dislike migration isn’t the migrants themselves, but the pressure they put on other inadequately addressed problems. Add migrants to a cost of living crisis, a housing crisis, and generally inadequate infrastructure, and things will get worse in the short-run.

But cutting migration isn’t the Band-Aid solution to crises caused by government failures in monetary policy, taxation, land-use regulation, and infrastructure provision that the median voter might think it is. Sometimes, such as when it’s a shortage of labour causing the issue, they can even be the short-run solution. In the longer run, taking in fewer migrants raises even bigger issues, such as how to deal with a more rapidly ageing population.

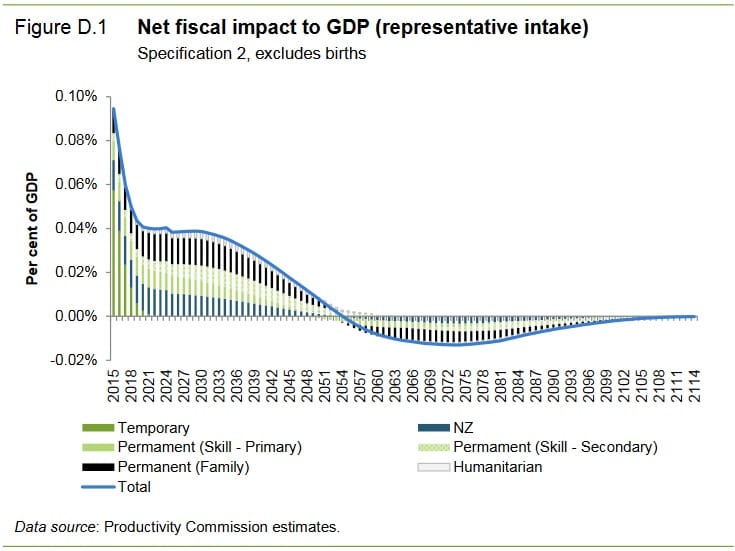

Of course, there’s always a chance the migration backlash is just temporary. Politicians tend to target migration during election years but once all is said and done, they may not be able to resist higher rates of migration. That’s partly because most of the fiscal cost of migration is initially borne by our state and local governments (the GST’s horizontal fiscal equalisation helps even this out over time), while the federal government collects most of the benefits. And as a double bonus, most of those fiscal benefits accrue in the earlier years of a migrant’s arrival, with the costs occurring out beyond 40 years.

If you’re a politician and you want to spend on something without making cuts elsewhere, a higher rate of migration is a good way to ‘find’ a bit more cash in the budget. According to Treasury:

“All other things equal, a permanent migration program with a positive fiscal impact allows taxes to be lowered, government debt to be reduced or spending to be increased across the population.”

Australia relies heavily on migrants to offset its ageing population and fix the fiscal problems that have come from governments borrowing against the future to spend in the present. I fully agree that this is a far from ideal method of dealing with these issues. But absent fiscal rules, tax and entitlement reform, and a complete change to how land-use regulation is done, it’s the cheapest, easiest, short-term fix for our problems. That’s why for our political class, it has been on rinse and repeat for many decades.

But for the sake of argument, let’s just say Australia does permanently slow down its rate of migration. How might that change our future?

Rethinking entitlements

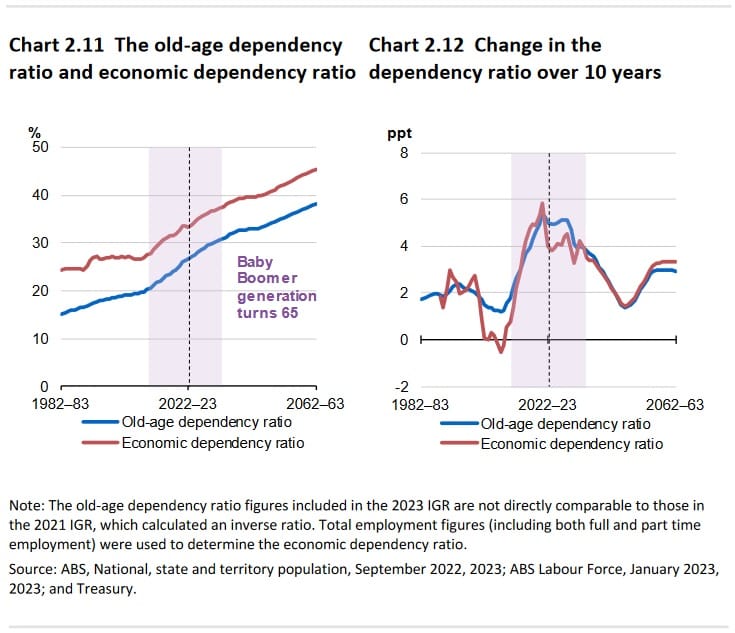

Australia is ageing, even at current rates of migration. Treasury’s most recent Intergenerational Report used a long-run annual net migration assumption of 235,000, a number opposition leader Peter Dutton wants to “bring back… to a figure of about 160,000”, or a cut of around 30%. But even with Treasury’s higher number, the outlook was for an older Australia:

“The population is expected to continue to age over the next 40 years. The median age is expected to increase by 4.6 years to 43.1 in 2062–63. The share of the population aged 15 to 64 will fall by 3.5 percentage points to 61.2 per cent between 2022–23 and 2062–63. Over the same period, the share of the population aged 65 and over is expected to increase by 6.1 percentage points to reach 23.4 per cent.”

As a result, our old-age dependency ratio will keep rising, putting pressure on government budgets. With a permanent cut to net migration, the ascent will be even steeper.

Without the sugar hit of migration, policymakers have a few options to deal with the fiscal implications of a much older population. The first is entitlement reform: the Baby Boomers, being the large voting block that they are, have promised themselves a lot of goodies at the expense of their children and grandchildren. They are the generation that " paid in less and took out more from the welfare state than any generation before or since". For example, while residential aged care is means tested, payments are capped at $33,000 a year, or $78,500 over a lifetime. As a result, 96% of the costs are picked up by taxpayers.

I’m sure there are many other examples, such as how the family home is exempt from the pension means test. Yeah, forcing a pensioner to sell her 4-bedroom inner suburb home is harsh, but that’s exactly what we need to happen if we want to free up well-located land for families. I mean, should we really be paying a pension to someone who owns a million-dollar asset? Reforming state taxes so they’re not so dependent on stamp duty would be one way to make that whole process a bit less of a stinger, and boost economic efficiency to boot.

Anyway, means testing all of our entitlement programs so that we don’t spend ourselves into fiscal oblivion by making payments to seniors who don’t need them is probably the main way we can afford a permanent cut to migration. There really isn’t much of a moral case for government subsidising wealthy people just because they’re old. And there certainly isn’t an economic one; it’s pure politics – the Baby Boomers are still the largest single voting cohort in Australia, and are by far the wealthiest.

Housing and the baby crisis

Another way to pay for lower rates of net migration would be to get fertility rates back up. An oft-cited reason for Australia’s declining fertility and our " baby crisis" is expensive housing. It makes intuitive sense; if you can’t afford a house – or can only afford one later in life when your fertility isn’t as good – you’re probably going to be less likely to start a family.

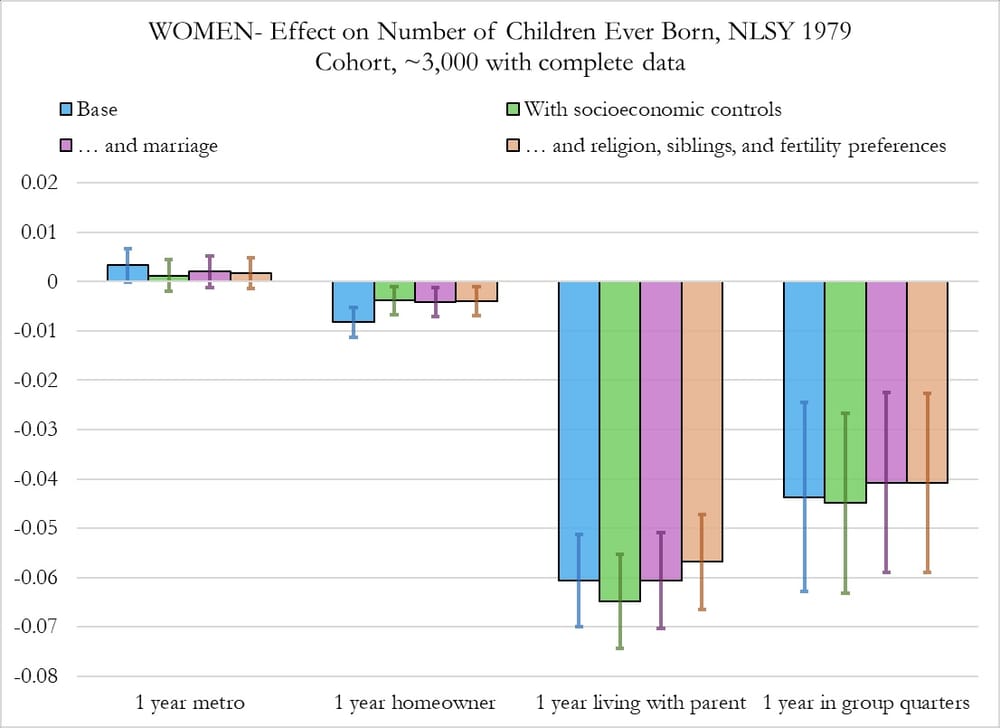

There is research to support this theory, too. Demographer Lyman Stone recently looked at factors affecting fertility in the US and found that for women, living with their parents or in shared accommodation (e.g. a dorm) had quite large effects on how many children they ended up having.

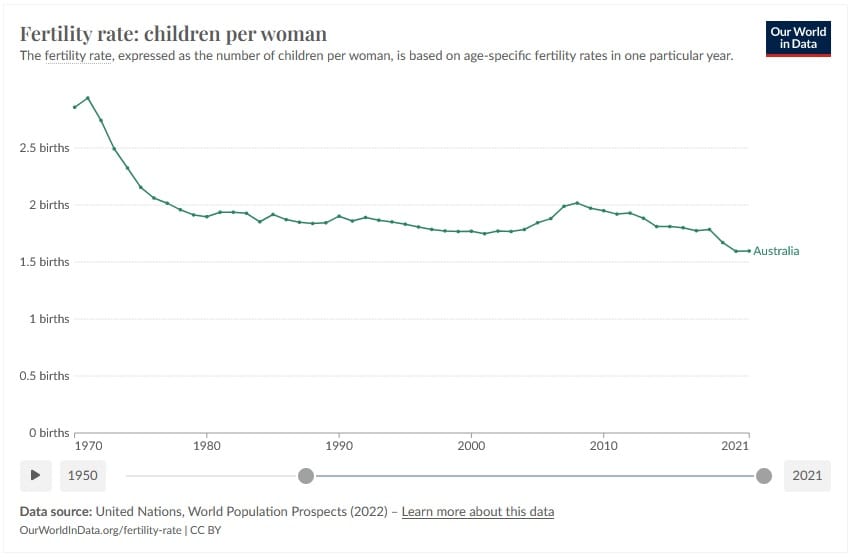

So, you would think that more expensive housing would keep people at home longer and, all else equal, mean fewer children are born. But all else is never equal, and I’m not so sure that housing costs are the causal factor here. Fertility rates in Australia have been relatively stable since the late 1970s, when the house price to income ratio was less than half what it is today.

But what matters more than house prices is housing affordability. If borrowing costs come down – which they have since the 1970s – people can afford a bigger loan relative to their incomes, or save a smaller deposit.

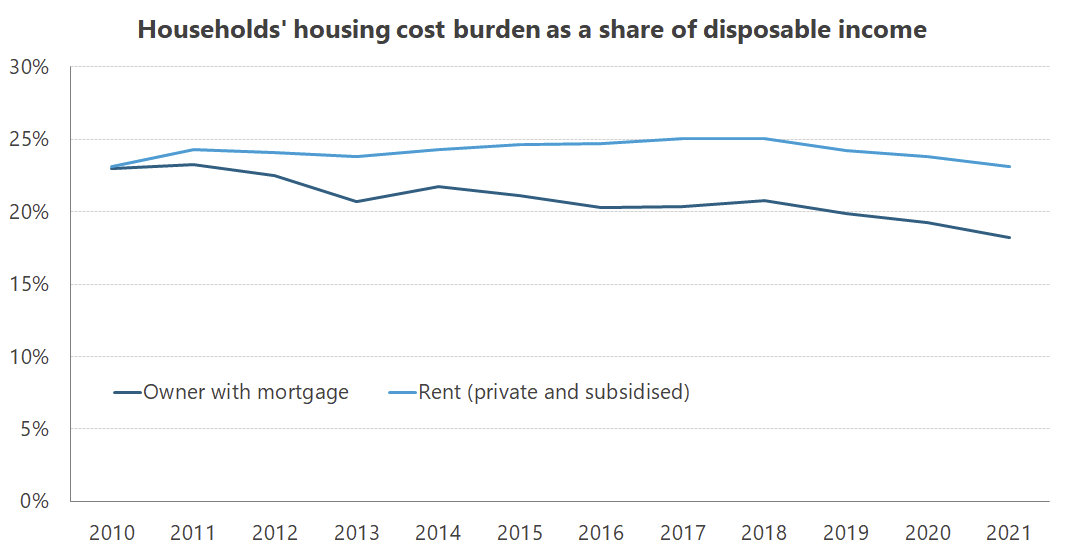

Yet despite the near 25% decline in fertility since around 2009, housing costs have been flat (renters) or falling (mortgage holders).

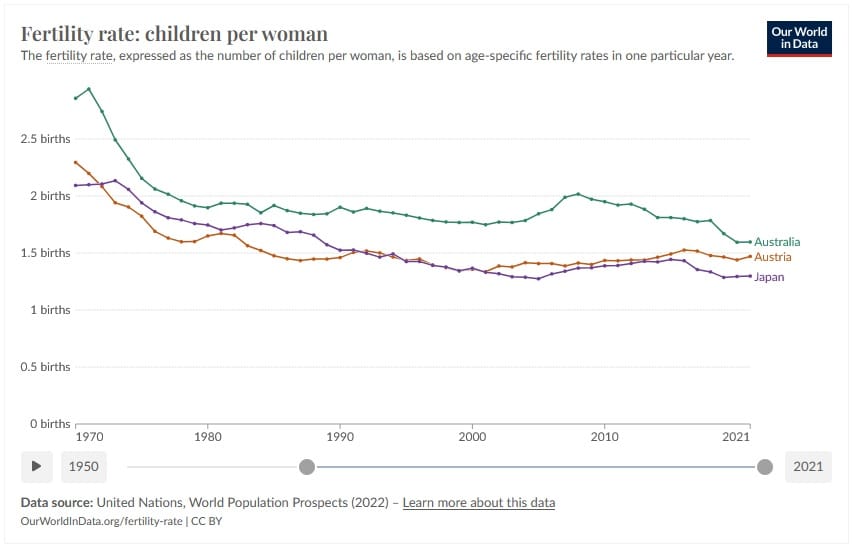

To me, that suggests something other than housing costs are keeping our fertility rates down. I don’t know what it is, but it’s not unique to Australia. Even countries that build a lot of affordable, market-rate houses such as Japan, or have a considerable stock of social housing such as Austria, have fertility rates and trends that don’t look all that dissimilar to our own.

While women in richer countries have historically had fewer children, the relationship no longer holds. Perhaps the most important factor in improving fertility in high-income countries, such as Australia, is ensuring compatibility between women’s careers and families:

“Policymakers should take note and take a career-family perspective. Investing in gender equality—and especially the labour market prospects of potential mothers—may be cumbersome in the short run, but the medium- and long-term benefits will be sizable, for both the economy and society.”

That suggests that fertility can be ‘fixed’, provided governments are willing to prioritise it over the medium- to long-run. Because of the power of compounding, a policy which sustainably (ruling out a repeat of Costello’s baby bonus) raises birth rates even by a small amount will yield a much larger population decades later. A population that’s growing sustainably can then afford to pay for various luxuries via taxation, including our old-aged entitlements.

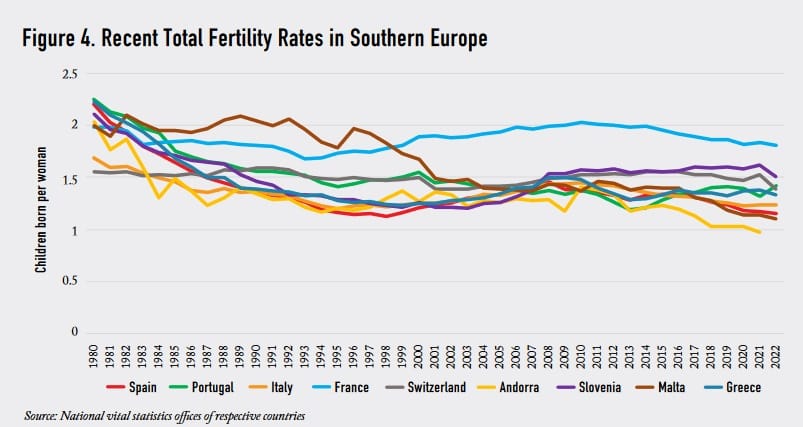

Interestingly, France has done comparatively well on that front.

France’s success hasn’t come from its culture, such as high rates of marriage or religiosity. In fact, in France 60% of children are born out of wedlock, but only 2.8% lack a registered father (for context, in the US only 40% of children are born out of wedlock but 11% of births have no registered father). While the presence of a father can be very important for children’s development, the culture of marriage doesn’t seem to be that important for fertility.

France’s relatively high fertility rates are because of the pro-natal policies its government has been undertaking since at least 1920. Those policies have caused France’s population to be “several million people higher today than it otherwise would have been… [and] is explained entirely by higher birth rates of native-born women, i.e. not migrants”.

Those policies include a family cash-allowance and a generous tax scheme known as the “Quotient System”, which divides taxable income by the size of the household. The first and second kids only count as 0.5 people, but after that they’re full people for tax purposes. So a family with three kids where one person is working would be able to reduce their taxable income three-fold compared to the same family in Australia. Incentives matter!

Australia has its own, much smaller baby incentive scheme called the Family Tax Benefit, past increases to which have been associated with a rise in women’s intended number of children. But if we want to cut migration and make up for at least some of it with higher fertility rates, then we’ll need to go a lot further than that. Importantly, there is no silver bullet; it will take a combination of policies working in tandem to raise fertility rates.

And we’re learning more every day: for example, a new paper found that even something as seemingly small as childcare regulation (which raises childcare costs) can have an appreciable impact on women’s fertility decisions. So perhaps there are also changes we can make without having to pay all that much.

Are we doomed to go full circle?

Migrants are, as a whole, good for Australia – at least the types of migrants we have historically welcomed. But they can also worsen self-inflicted issues such as the housing crisis, which the Productivity Commission found to be “exacerbated by the persistent failure of successive state, territory and local governments to implement sound urban planning and zoning policies”.

Just as painkillers can mask the symptoms of an underlying condition, in the short-run, cutting migrants can ease problems such as our lack of housing. But beyond the short-run, fewer migrants will make life more challenging. For a start, to sustain our ageing population, deeply unpopular decisions will have to be made, including cutting entitlements. Indeed, most of Australia’s demographic issues today have come from people living longer, rather than from falling fertility, so “fertility and immigration are not effective solutions to such fiscal challenges”.

But if the government cuts migration and does nothing about fertility or resolving our mountain of existing policy failures, those fiscal challenges will quickly become exponentially more difficult.

The thing is, an older population shifts the tax base and changes the composition of government expenditure to old-age related items. In the past, both Labor and Liberal parties have been able to ignore the trade-offs of migration, restrictions on housing supply, and age-related entitlements because our demographics were favourable and interest rates were low, meaning the costs were always many years in the future.

But that future is getting an awful lot closer, and when it comes, we’re going to need much more generous (read: costly) fertility incentives and will have to start getting serious about fiscal reform. That, or a future government will once again turn to the cheapest, shortest-term solution we have to delay such problems: net migration.

Comments

Comments have been disabled and we're not sure if we'll ever turn them back on. If you have something you would like to contribute, please send Justin an email or hit up social media!