Australia's nuclear energy debate

Last week I watched a nuclear energy debate between Simon Holmes à Court, the son of Australia’s first billionaire, and the Centre for Independent Studies’ (CIS) Aidan Morrison, which – while cordial – quickly devolved into a match to see who could best talk past the other person (for reference, that would be Holmes à Court).

Basically, Morrison spent his time pointing out flaws and missing details in the Albanese government’s model (the Integrated System Plan or ISP), while Holmes à Court said none of that matters unless Morrison can produce an alternative model with nuclear power in it (“you haven’t done the work to show people that there’s a better plan”).

Fair enough, I suppose; but then what was the point of the whole thing? During the debate, Holmes à Court certainly wasn’t willing to put up the $500k he suggested such a model would cost to develop, despite his family’s net worth being something like 1,000 times that much. You might think that someone who only wanted the best for the nation would be open to funding that kind of work. But I digress.

By far the most cringe moment came at the 42 minute mark, when Holmes à Court said that discussing the full system costs, rather than only the levelised cost of electricity (LCOE), was “an absolute red herring that you’ve [Morrison] introduced into the debate to confuse people on this, but is a key source of your confusion on the ISP, and please, let’s sit down and have someone explain it to you in detail”.

I don’t watch many debates, but I suspect that kind of condescension is not a good way to win over neutrals; it certainly made me question Holmes à Court’s sincerity. Even more so after I asked a large language model about it:

“Full system costs are a metric used to compare the cost-effectiveness of different technologies. They account for costs that occur beyond the power plant, such as the total costs of supplying electricity at a given load and security level.

The LCOE is used to compare different methods of electricity generation and for investment planning. It’s the average revenue per unit of electricity generated that’s required to cover the costs of building and operating a generating plant.

The LCOE doesn’t consider all costs associated with a financial decision, and it can oversimplify the project context. The LCOE of different power plants can vary depending on the region or regulatory environment.”

That… seems like an important distinction worthy of discussion, no? For example, a recent report by Frontier Economics added in a bunch of other costs – such as transforming the grid in WA and the NT, rooftop solar and home batteries, transmission costs – and found that the government’s transition was more likely to cost $642 billion, not the oft-cited $122 billion (which, it turns out, is actually a net present value estimate, not what consumers will actually have to pay).

I also noted other contradictions in Holmes à Court’s argument. For example, he dismissed nuclear because of Australia’s relatively high construction costs, saying that we would never be able to build it as cheaply as China. But only a few minutes later those constraints miraculously vanished; if Australia goes all-in on renewables, says Holmes à Court, then because hydrogen can’t be shipped and that’s all we can do with the surplus power we’ll need to keep the lights on (more on that in a bit), then we’ll see an onshoring of minerals processing to Australia because we’ll be the cheapest place in the world in which to transform things like iron ore and spodumene into green steel and batteries.

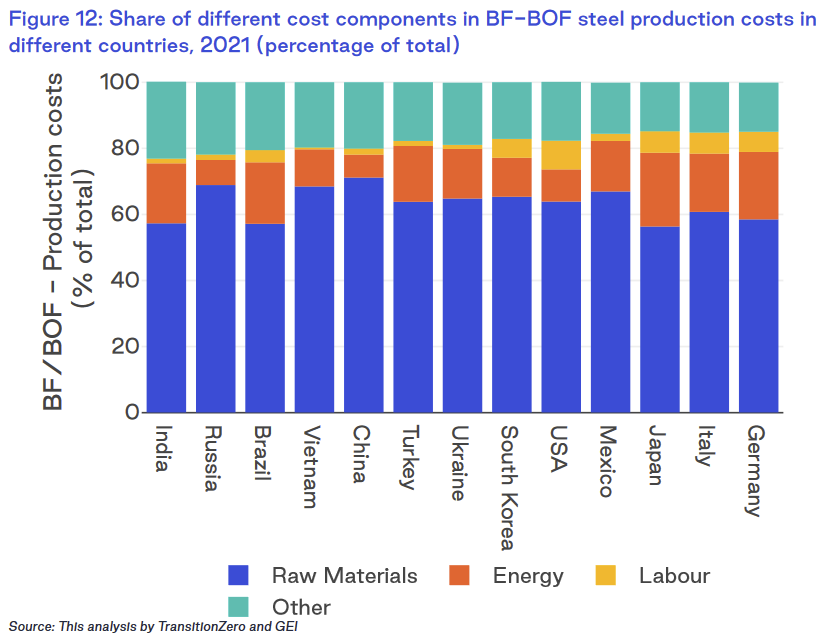

Except… we won’t? Steel making certainly uses a lot of energy, but it’s still only ~20% of the total production costs in most countries, and is even lower in China.

There are also geographical constraints. For instance, most of our renewable power generation will presumably be near where people live – i.e., primarily in the South East of the country – not where our iron ore and spodumene lithium are located, which would be the North West.

We already have world-leading infrastructure to ship iron ore – the largest cost component in steel making – directly to countries like China and Japan for around US$10/tonne, and they already have the infrastructure to transform it and ship it back to us as fridges and cars.

To transfer that function to Australia would require getting a lot of people to the North West, or a lot of iron ore to the South East. Neither would be cheap; the former would likely involve a large fly-in, fly-out workforce because so few people want to live in the hot and humid Pilbara region, while the latter would involve huge construction costs – e.g. a cross-country bulk freight railway, or major road upgrades and a fleet of trucks. Then we would also need a brand new port from which to export all the green steel, because we certainly wouldn’t be able to use it all in Australia.

Even if Australia had the world’s cheapest energy, I can’t see a way to reduce the other costs – raw materials, labour, “other” – enough for it to stack up. I mean, just because we (the government) technically “own” the iron ore and spodumene doesn’t mean anything; someone still has to pay to explore for it, build the necessary infrastructure, mine it, and move it. That’s not free, and investors need a competitive rate of return to finance all of those activities, so the correct assumption to use is the global price for the relevant commodity, not some fictitious near-zero domestic Australian price.

Could we “reserve” some of it, as we do with gas? Sure, but there’s very little rationale for doing so. “Steel security” doesn’t have the same ring to it as “energy security”, and reservation policies are costly: estimates of Western Australia’s 15% natural gas reservation suggest it “imposes an overall net loss to the nation of around $600 million each year”.

I worry that the obsession with “onshoring” manufacturing amongst our elites is going to cause serious economic damage.

Why green steel is so important

I said I’d describe why I thought Holmes à Court was so keen on hydrogen and “onshoring” manufacturing to Australia, so here goes. It’s because of the fundamental weakness of a renewables-dominant grid: what to do with the surplus power in the middle of the day, and the shortage when people most want to use it. The infamous “duck”:

Basically, renewables don’t generate power when people want it. That means to keep the lights on with a renewables-heavy grid, you need some combination of overbuilding and storage ( e.g. hydrogen, batteries, pumped hydro) and backup generation (e.g. gas).

That’s no easy feat; in Germany, they already have a word for when it goes wrong – dunkelflaute, or “dark doldrums”:

“Early November has brought a prolonged period of little wind and sunshine in Germany and many other parts of Europe, bringing down renewable power generation and leading to a spike in electricity prices and the use of fossil fuels… Data by Fraunhofer ISE showed that renewables contributed 30 percent to public electricity generation, while fossil fuels covered the remaining 70 percent between in the week between 4 and 10 November.”

This problem gets more severe the greater the share of renewables in the system:

“To reach 50% wind penetration, Denmark would have to increase capacity from 4,500 MW to 7,650 MW. But if Denmark plans to go from its current level of 33% to 80% wind penetration, it would need to do much more than increase its capacity by a factor of around three; it would need more than five times as much as it has now. As Roger Andrews points out, the waste would be staggering, with almost 90% of every MW of added generation and over 50% of total wind generation getting curtailed.”

Unlike Denmark, Australia isn’t physically connected to Norway, Sweden and Germany, which gives it “access to an additional 5,820 MW of interconnector capacity that it makes full use of the Nordic Grid, where other countries provide non-wind/non-renewable energy when the wind is not blowing in Denmark”.

We’re on our own. That means we need to overbuild generation capacity so that we can still eke out energy for our batteries when we inevitably get a dunkelflaute moment. But overbuilding to the extent that you have to “curtail” (i.e. dump) most of your surplus makes zero economic sense, which is where things like green hydrogen come into play: when the batteries are full, the sun is shining and the wind is blowing, hydrogen can be created for “free” and then used by industry or to generate electricity at a future date.

That’s why technologies such as green hydrogen are pivotal to the ISP, and the associated assumptions around industrial uses are so important: without that value added, a renewables-heavy grid is likely the most expensive option available.

Putting it all together

Look, a lot of what Holmes à Court said about nuclear is true. It will be expensive to build in Australia; Snowy Hydro 2.0 cost $12 billion, for goodness sake – 500% more than the original estimate.

Legal advice suggests that a future Dutton government would be able to override the states, “so long as the commonwealth enacts laws that are valid, that are supported by the Constitution”. But there are just so many ways that vocal minorities can throw sand into the gears of progress, and it would be silly to assume that won’t also apply to nuclear.

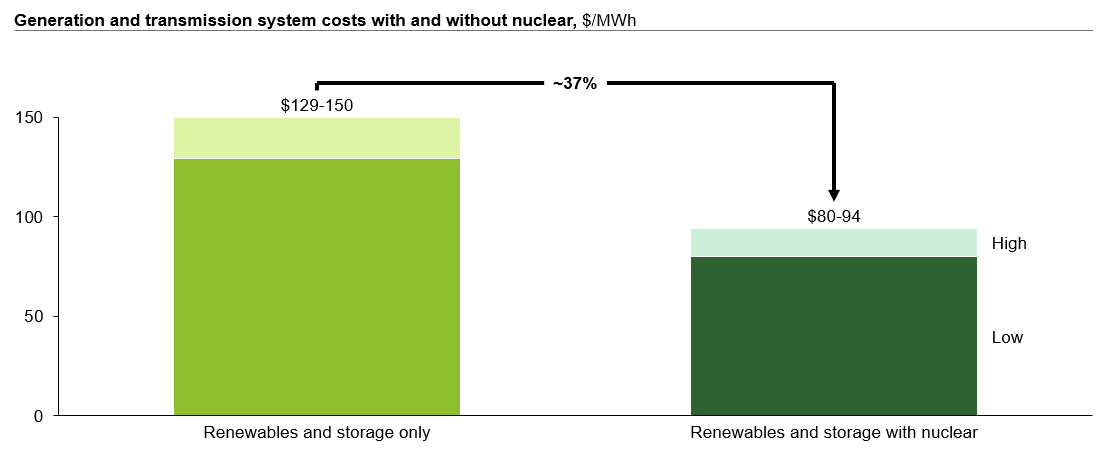

However, if there was a way to get nuclear into the mix, I think it would be a net positive for the nation. Not just because, with a third of the world’s uranium reserves, it would guarantee some semblance of energy security. But because adding it can bring total costs down:

That’s from the Biden administration’s US Department of Energy, so is probably more impartial than a partisan think tank or renewables-invested rich guy. Nuclear brings total costs down because it provides the “clean firm capacity” needed to support and scale a renewables-heavy grid:

“Clean firm generation reduces the need for building additional variable generation capacity, energy storage, and transmission. Despite the low capital and operating costs of variable renewables, system decarbonisation with only variable renewables and storage results in higher system costs because of the volume of generation capacity required for adequacy and reliability (and subsequent decrease in marginal value and utilisation rates). Additionally, firm technologies can produce electricity during the most expensive hours when wind and solar are unavailable. Even when priced at a premium per unit of energy, the inclusion of clean firm resources reduces overall system costs.”

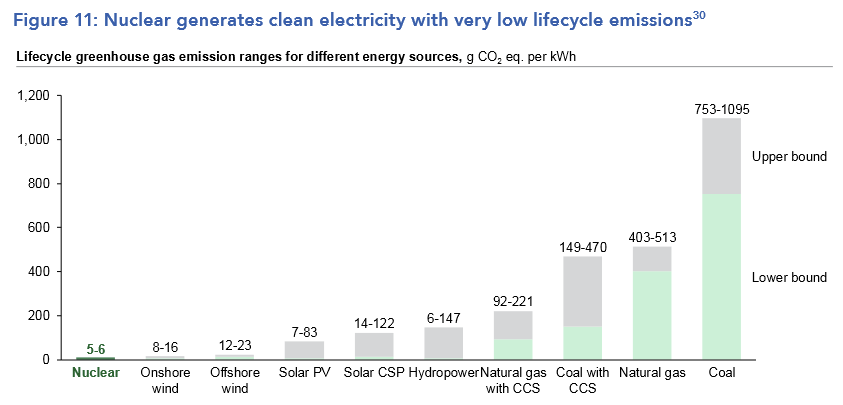

Nuclear doesn’t compete with renewables, it compliments them. The choice isn’t renewables or nuclear; it’s whether we go with renewables and fossil generation (e.g. gas) with carbon capture, or renewables and nuclear. According to the US Department of Energy, if your goal is to reduce emissions with the smallest possible footprint in the safest way possible, you can’t do much better than pairing renewables with nuclear:

I think the current political debate is doing Australians a disservice, because it’s being framed as renewables or nuclear ( Energy Minister Chris Bowen is, anyway).

But given that going above ~80% renewables is expensive because you need to significantly overbuild generation capacity to prevent blackouts – “it’s cheaper to squeeze more electricity out of a short cold cloudy day than it is to carry around a spare day’s worth of batteries you might use once per year” – the real choice is to renovate or rebuild our aging coal and gas facilities, or transition towards nuclear. Under either scenario, there’s no reason why renewables shouldn’t comprise the majority of Australia’s energy generation.

Indeed, as time passes and problems with the current path keep stacking up – e.g. endless subsidies to prop up industries that were supposedly going to benefit from cheap renewables that aren’t actually that cheap because energy prices are determined by the marginal unit, not the cheapest one – the more I find myself siding with the nuclear option.

Comments

Comments have been disabled and we're not sure if we'll ever turn them back on. If you have something you would like to contribute, please send Justin an email or hit up social media!