Australia's nuclear option

It’s official: if the Coalition wins the next federal election, Australia will be on the path to becoming the last of the top 15 countries in the world by national income to generate nuclear power. Technically Italy and Germany don’t produce it any more, but they still import it from France. Italy is also looking to build new plants, as is Indonesia, which will probably enter the top 15 soon enough.

Here’s the AFR describing the recently-released modelling behind the Coalition’s nuclear plan:

“The costings, conducted by Frontier Economics and to be released on Friday by Opposition Leader Peter Dutton and energy spokesman Ted O’Brien, estimates the capital and operating costs of the Coalition’s policy to deliver net zero emissions electricity by 2050 will be $331 billion.

By contrast, Frontier’s managing director Danny Price, who conducted the modelling, found Labor’s policy, which is based on the energy regulator’s Integrated Systems Plan, would cost $594 billion.

…

The modelling, according to those familiar with it, attributes the cost discrepancy between the two policies to not having to build new transmission infrastructure, keeping coal in the system for longer, and the economics of running nuclear around the clock as a baseload power.”

Various commentators have pointed out issues with the modelling, such as the lack of plans for waste and decommissioning, or that it was only costed over 25 years. But those limitations also apply to Labor’s ( AEMO) modelling, so I’m not going get into the nitty-gritty of what was inevitably an extremely technical exercise with a long list of assumptions, most of which would have involved a healthy amount of judgement.

I’ll only add that it’s good to see Frontier Economics including transmission costs in its modelling, something the CSIRO’s GenCost report ignores when it assumes them away by using the levelised costs of electricity, or LCOE. As a 2022 paper by Robert Idel published in the journal Energy concluded, such a methodology is… problematic in the context of an energy transition:

“Intermittency of generation makes the cost comparison between different generation technologies much more difficult. While being a good measure to evaluate the cost to generate electricity, the most popular cost measure, the Levelised Costs of Electricity, fails to include the costs associated with meeting the demand and providing usable electricity.

…

Using the radical but straightforward assumption that each source of generation has to meet the demand over a given year (with the help of storage), the Levelised Full System Costs of Electricity introduced in this paper are the first cost measure to condense the cost of providing electricity to one number per market and technology. With LFSCOE being much higher than the LCOE for wind and solar, it becomes evident that LCOE are far from being an accurate measure to include the cost of intermittency.

Analysing different sources of generation sources shows that the LFSCOE are much higher for wind and solar than for conventional and dispatchable fuels, which stems from the large requirement for storage to overcome wind and solar’s intermittency. However, even if these storage costs drop by 90%, renewables are still not competitive on an LFSCOE basis.”

Basically, the cost of a renewables-heavy grid grows exponentially the closer you get to 100%. As Idel found, going from 90% to 100% renewables doubles the total system cost. So you will always need some kind of “dispatchable generation to support renewables”, and other than pumped hydro (which isn’t available everywhere), nuclear is the cleanest and safest of what’s available.

If we take the energy transition as a given – and politically, that certainly seems to be the case – then the debate isn’t really about nuclear versus renewables; it’s nuclear versus gas and coal.

So, how does nuclear stack up? Even ignoring the modelling issues, there’s plenty to unpack in the Coalition’s plan. To start, I think the timeline is unrealistic. The first plant is expected to be operational in 2036, which is about how long it took the United Arab Emirates (UAE) to get its Barakah nuclear power plant going. That facility now generates 25% of the nation’s energy – enough to power the state of Victoria.

South Korean nuclear experts help the UAE build its first facility. Source.

South Korean nuclear experts help the UAE build its first facility. Source.

But Australia isn’t the UAE; Snowy Hydro 2.0 was supposed to be done by now, at a cost of $2 billion. Now it’s not due for completion until at least the end of 2028, at a cost of $12 billion. That figure increases to $25 billion if you include its transmission requirements.

Meanwhile, the UAE built the Burj Khalifa – the tallest building in the world – in just six years. For various reasons we can’t build much of anything these days, whereas countries like the UAE have no such issues.

Basically, even if Dutton secures the votes to legalise nuclear power, he’s going to have a huge fight overcoming NIMBYs, environmentalists and other obstructionists who have been perfecting their trade for many decades, and will have the support of every state government.

It won’t be easy!

I also think the Coalition’s plan is too ambitious, too centralised, and doesn’t do anything to address the fundamental flaws with the current network. Don’t get me wrong; I think nuclear is important from a security point of view and we should want to keep all of our energy supply options open, especially after the AUKUS submarine deal. I would love nothing more than for it to be legalised and a nuclear-friendly regulatory regime established, with the playing field levelled by ending the web of subsidies and regulations that make it difficult to evaluate the costs and benefits of competing energy sources.

But I also know that politically, such a sensible outcome is likely to be impossible. So if you must build nuclear through political discretion, instead of committing $331 billion towards seven nuclear plants, why not start with a $50 billion facility in, say, Victoria, where they’re so desperate for dispatchable energy there’s even talk of building LNG import terminals?

For context, that sum is about the equivalent of a single year of the NDIS, an entitlement scheme that didn’t really exist a decade ago – surely a small price to pay given the potential upsides in energy security, emission reductions, and economic resilience.

I mean, it’s not like we don’t literally burn money in plenty of other places: $3.4 billion on French submarines that we didn’t even get. $4 billion on hydrogen, which is uneconomic even with subsidies. $3.5 billion worth of electricity credits to households. $22.7 billion on a Future Made in Australia, which includes things like a vote-buying quantum computing facility in Queensland and a solar panel manufacturing facility in the Hunter Valley.

Trim some of that fat and the first nuclear facility is basically free, right? Once Victoria’s plant is operational, any peak period surplus could then be exported to South Australia, given how far along the road to energy uncertainty it is (it’s using diesel and imports from other states to keep the lights on).

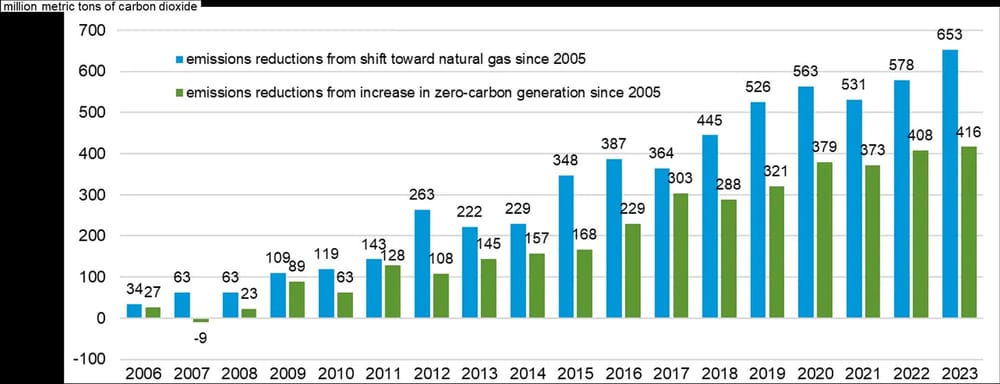

In states where gas is more readily available, that could be used to gradually replace coal as the despatchable energy source to firm the network, for about half the CO2 emissions. Indeed, across the world the substitution of gas for coal " has had a greater decarbonising effect in aggregate than increased renewables", so it’s not like we’d be shirking in our effort to reduce carbon (even though Australia only contributes around 1% of global emissions):

While the first reactor is being constructed, Australia will build its nuclear know-how, more talent will be attracted to the sector, and innovations here and overseas will have time to develop – and who knows what that might mean for the future (perhaps small or micro modular reactors will be economical by then?).

And therein lies another problem with Dutton’s plan: committing to so much large-scale nuclear up front risks locking Australia into an older, centralised energy model, leaving the network open to grid defection:

“Grid defection occurs when electricity customers generate and store enough power locally to become fully self-sufficient and disconnect from the central utility grid. This typically involves using technologies such as solar panels, wind turbines, and energy storage systems (e.g., batteries) to meet all energy needs independently.”

As the price of solar and batteries fall, so too will the risks of large-scale defection. In an increasingly decentralised energy landscape, the traditional utility business model might be upended, and these new nuclear facilities – owned by the government – will be at risk of becoming huge white elephants.

I also worry about the incentives such a model creates for future politicians. The true cost of electricity is already being hidden from investors and consumers through various subsidies, regulations, and the lack of widespread time-of-use pricing, so there’s no incentive for them to change their behaviour. If the Coalition injects a bunch of nuclear power into the mix and if solar and battery prices keep falling, the only way to keep households and firms from defecting – and nuclear power operators from going broke, as coal operators are today – will be through endless subsidies. The more people that defect, the more expensive the higher the fixed network costs become, leading to an even greater subsidy burden.

To be clear, this is also a problem for Labor’s renewables plan. However, unlike the government-owned nuclear option, Labor’s subsidies won’t leave taxpayers holding the bag if it all goes tits up, unless you consider nationalisations and investor bailouts a possibility – and you absolutely should.

But artificially suppressing energy prices with subsidies will also make the current renewables problem worse, because it prevents market-based solutions from emerging at all: when prices aren’t allowed to function, political decisions are used in place of individuals weighing the costs and benefits of each energy source.

Now, we can’t know how people would respond to higher prices, only that there would be a response. Energy demand curves are downward sloping, so as the price rises, the quantity demanded will decrease until people come up with new methods to increase supply.

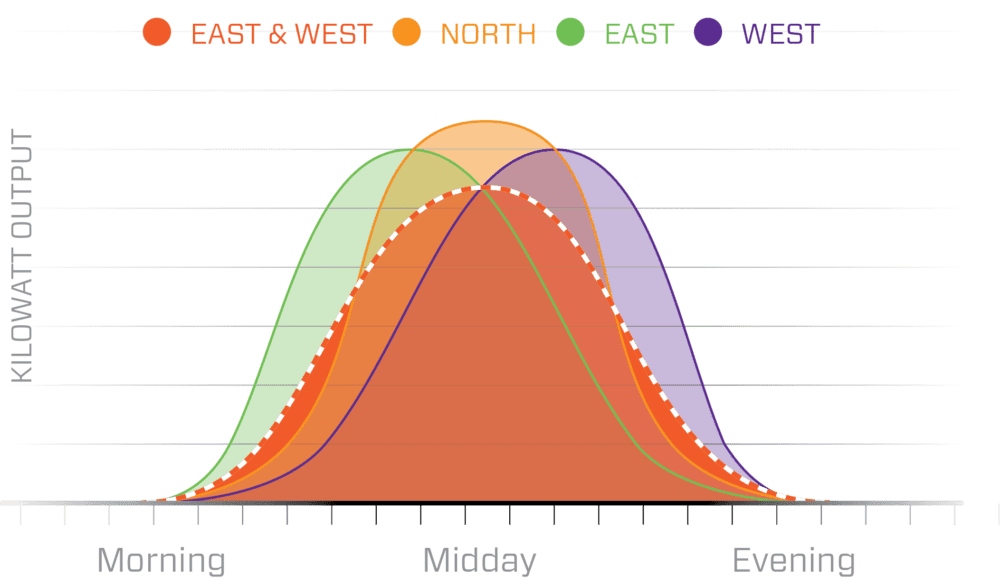

Here’s just one example: if people were aware of the true cost of energy then perhaps instead of installing north-facing solar panels, they would opt for a split east/west layout, reducing overall generation but increasing the amount produced during the peak morning and evening periods when prices are higher.

Consumers might also invest in batteries or EVs, so that they can pump some of the solar power they’re generating while they’re at work back into the grid in the evening, or even remove themselves from it entirely.

Economists like to say that the cure for high prices is high prices, but you’ll never discover the cure if you stop prices from working their magic. If you’re worried about equity issues, cash transfers to vulnerable households are a much fairer and efficient option than dulling price signals for all.

Ultimately, there are no easy answers. The goal for energy policy should be abundance, and the way to get there is through a mix of price and regulatory reforms that clear the air, allowing governments, consumers and investors to discover what combination of generating and firming options makes the most economic sense for Australia. That mix may very well include nuclear, given that it’s a completely viable energy source with zero carbon emissions, unlike coal and gas (which would lose much of their appeal if their externalities were properly priced).

Unfortunately, a commitment to meaningful reform just isn’t as sexy as expensive “solutions”, which is why we get so much of the latter. No matter who wins the next election, the energy debate looks set to descend even deeper into an ideological shouting match between a lot of renewables versus a lot of nuclear, when it should be about ensuring the energy sector functions as a reliable, contestable market.

But for that to happen would require leaving the tribalism at the door and conversing like adults, something our political class – the kakistocracy, or “the rule of the worst”, which I recently learned was The Economist’s 2024 word of the year – seems incapable of doing.

Comments

Comments have been disabled and we're not sure if we'll ever turn them back on. If you have something you would like to contribute, please send Justin an email or hit up social media!