Australia's renewables reality check

This is somewhat of a follow up to Friday’s post on the energy debate. Basically, I think Australia needs to work towards energy abundance and I don’t care how we do it, just that we get there!

In my view, to achieve that goal requires an ‘all of the above’ energy policy. I also think the Albanese government’s current approach is problematic because it’s making similar mistakes to those that were made nearly two decades ago.

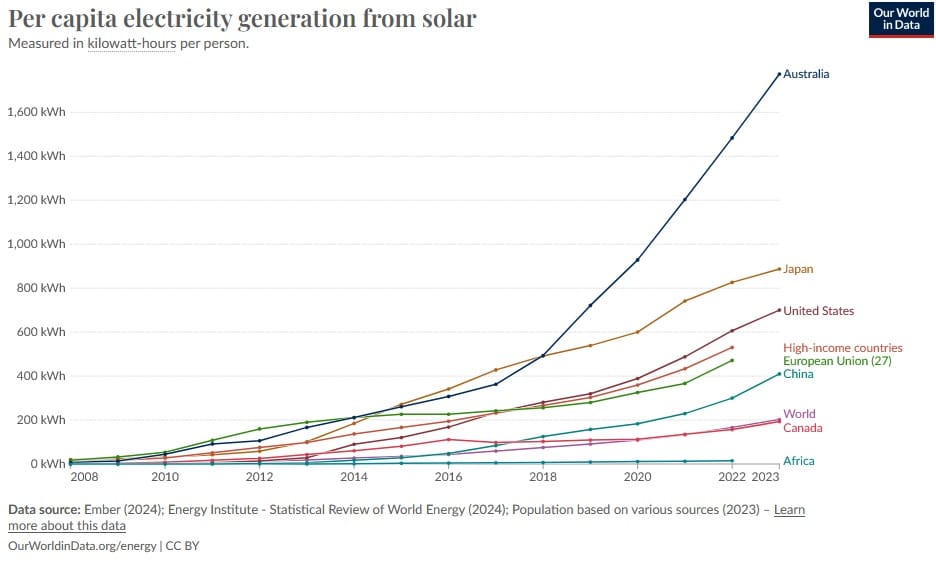

Back then various state governments, along with the Rudd/Gillard/Rudd federal governments, attempted to pull-forward Australia’s renewables uptake with large rooftop solar PV subsidies.

They meant well, and it worked well. Almost too well:

According to a 2015 report by the Grattan Institute:

“Subsidies driven by the federal and state governments have made solar panels affordable for nearly 1.4m households. And, many of these consumers invested in solar panels to make a contribution to addressing climate change as well as to save money. The problem has been that the subsidies have been very high and paid for, not by governments, but by other consumers. There have been benefits in reduced electricity production from big fossil-fuel power stations and reduced greenhouse gases, but the benefits have been outweighed by the costs to the tune of almost $10bn.”

The number of households with rooftop solar has since doubled to around 2.8 million, yet none of the problems with rooftop solar – all well known back then – have been addressed:

“Most data suggest that residential solar PV, the major focus of government in Australia, has little impact on reducing residential peak demand because the times of peak demand do not tend to coincide with substantial output from solar panels. A different picture emerges with commercial electricity consumers where demand more closely matches solar PV output.”

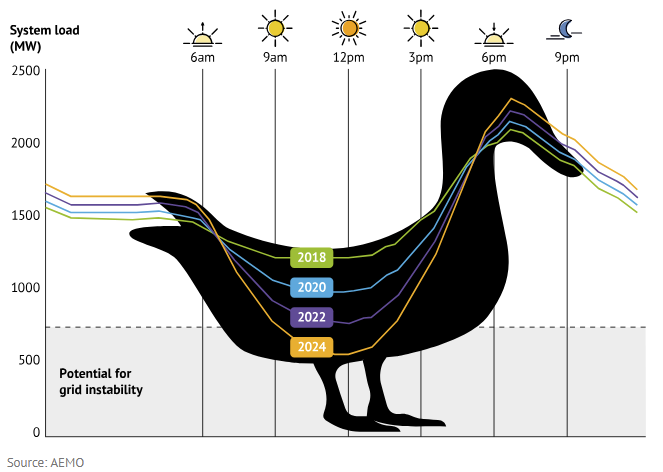

What the Grattan Institute is describing is the dreaded duck, where solar pumps most of the electricity it generates into the network precisely when it needs it the least, then fades away right as the peak period approaches:

It’s also inequitable. The subsidies that flow to the relatively well-off households with rooftop solar are paid by households that do not have solar, because “network businesses are allowed to recover the costs of these subsidies from their customer base, [so] subsidies paid to one group of consumers must be funded by another”.

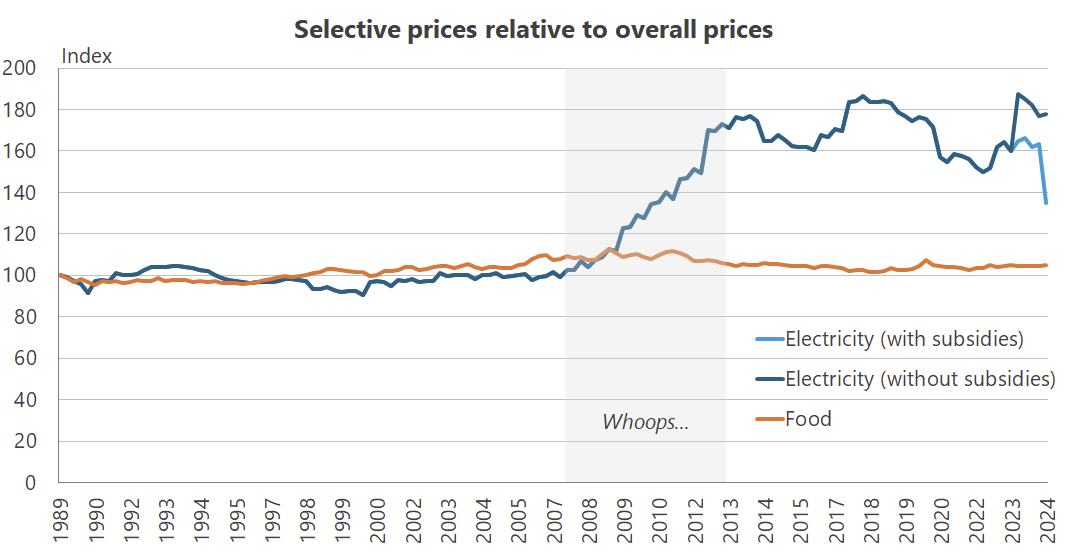

Solar power is basically free once it’s installed, but the electricity network is about a lot more than just the cost of generation. Households with solar PV require just as much network infrastructure as any other household, because while solar stops generating at about 6:30pm, peak demand is around 7:00pm. And rising network costs were the key driver of the run-up of prices between 2007 and 2013, due to aging infrastructure, the rapid solar roll-out, and some state governments opportunistically gouging households as a means “to fund government services instead of either increasing other taxes or cutting services”.

I’ve plotted electricity prices alongside food prices in the following chart, because while there have been a dozen or so supermarket inquires launched in just the past year, far less political energy has been spent asking the tough questions about the nation’s electricity prices (with the caveat that food makes up a significantly larger portion of a contemporary household’s spending than electricity):

Solving the duck

State governments could have at least partially resolved the problems created by the rapid rise of solar PV by having prices reflect the relative scarcity of power but, well… we all know what politicians think about prices, let alone owning up to past mistakes.

So, instead of dynamic pricing that correctly values the marginal unit of power when it’s not needed (e.g. during sunny days), with a high price when it is – which would significantly improve the business case for batteries – every state in Australia still offers households a solar feed-in tariff, and allows them to buy electricity on a flat-rate plan (time of use is optional).

The good news is that the market has started to catch up to the lofty dreams of our politicians. Battery prices have been falling virtually every year since the early 1990s, and keep getting smaller and lighter. But they’re still too expensive for most households at current electricity prices. I did my own calculation a few months ago and either my electricity bill would have to double, or battery prices would have to halve, for it to make sense to store some of the surplus solar I’m still being paid to pump into the grid when it least needs it, fattening the duck (Western Australia).

There are a few options to solve the duck. The first would be to allow prices to work. Basically, get rid of fixed rate plans and move every customer onto a dynamic, time-of-use pricing schedule – including for their solar feed-in. That would cause prices to rise during peak demand (e.g. evenings), with lower rates during off-peak periods (e.g. daytime when solar is abundant).

In such a regime, households that have solar panels installed would be incentivised to install a battery, bank their daytime solar generation, and pump any surplus back out into the grid when it’s actually needed and prices are high. Electricity bills would inevitably increase for most households until enough batteries were installed to supply the peak surge.

Another option would be to use a mix of subsidies and “nudging”, e.g. asking households to shift non-essential loads (say, washing machines) to off-peak periods. It’s a much less efficient solution but it’s also basically how our governments have avoided using proper usage-based pricing for water for this long, so it’s probably where they’ll go with energy, too.

You know, stuff like this:

Imagine a business paying for advertising telling you not to use their product!

Imagine a business paying for advertising telling you not to use their product!

Governments also like to throw money at problems, because they can be seen as saviours, rather than villains raising prices on households. So, more subsidies to solve the problem of previous subsidies will inevitably be par for the course.

Given that solar is quite useless without a means to store it, that means battery subsidies will be rolled out, such as the $2,000 proposed by former Labor leader Bill Shorten back in 2018. Or the NSW government’s new subsidy to incentivise households to buy batteries and “connect to a virtual power plant”.

Such policies are not going to be as effective as simply allowing prices to work. They’re also regressive: Australian households with solar PV tend to be those with the most accumulated wealth, so providing them with another transfer would fail most measures of equitable policymaking. But then middle class welfare has been music to Australian politicians’ ears for a long time, so it’s probably what we’ll get.

Repeating the same mistakes

It never should have come to the point where governments are subsidising batteries. If consumers had faced the true costs of their decisions, the solar PV uptake would have been more gradual – i.e. more in-line with that of the key supportive ingredient – batteries!

It’s a great case study in the dangers of pulling forward demand before the market is ready for it. Australia is just far too small of a market to influence global trends, so we should be careful not to set unrealistic goals funded with huge amounts of taxpayer dollars. Completely arbitrary targets, such as having 82% of the grid using renewables by 2030, are not just foolish but potentially wealth-destroying.

The unfortunate reality is that long periods of cloudy or windless days will still happen, and an electricity network has to be able to survive the worst-case scenario, not the best-case one; that means even with 82% renewables, capacity must be overbuilt by considerably more than that, which is costly.

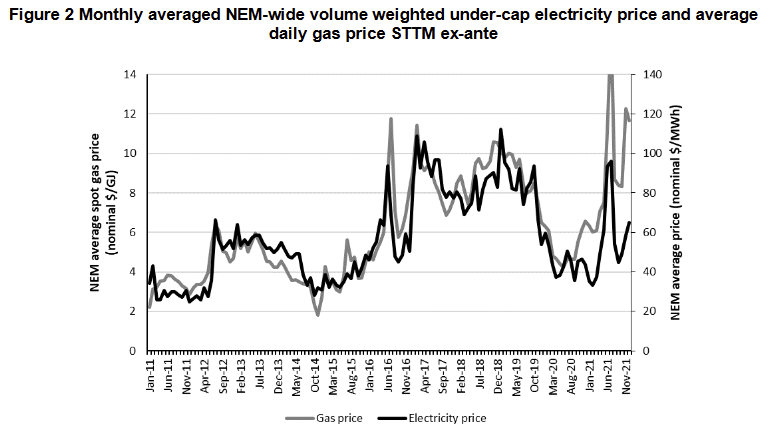

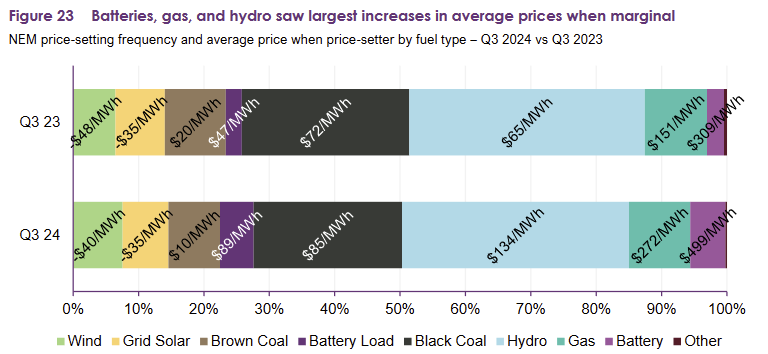

Network prices are determined by the marginal unit – i.e. the most expensive generator needed to meet demand – not the average unit, and right now that’s the gas burnt during peak periods:

As Australia’s installed renewables capacity has increased, so too has the frequency of“periods of tighter supply-demand and spot price volatility”.

To reduce electricity prices, Australia needs to lower the cost of the marginal unit. That can be done with cheaper gas, or better ways to store any off-peak renewables surplus, such as with a huge stock of batteries, hydrogen, or pumped hydro.

Basically, Australia is going to need many more batteries. But to achieve grid security, we’re also going to need a reliable source of energy that fills in the weaknesses of renewables and batteries – one that increases the grid’s reliable, baseload capacity while reducing demand for costly firming capacity.

That role is currently filled by coal, which very few people want to see continued forever – it truly is the dirtiest, most dangerous source of energy we have.

While hydrogen, pumped hydro, and large-scale battery energy storage solutions are possible alternatives, they’re all expensive and don’t scale. Wall batteries might eventually work for households, but if you want any kind of business or industry to survive and thrive, then you need reliable and affordable grid power.

There’s only one source of energy that ticks the boxes of taking risk away from the weather gods, ensuring future energy security, and grid scalability: nuclear power, which can provide a consistent and reliable supply of baseload capacity, dispatchability, and grid stability while generating no carbon emissions. Gas is a second-best option, given it still emits carbon – about half as much as coal.

But there’s no way to get nuclear quickly; it would take at least a decade for a country like Australia, where it’s still banned, to complete a single plant. And even if we eventually got there, for the next couple of decades it means we’re either going to have to sacrifice energy security with an increasingly renewables-heavy grid, keep the dirty coal power plants running for significantly longer, or start pumping or importing a helluvalot more gas to get domestic peaking prices down until batteries get much cheaper.

Or most likely, some combination of all three.

Comments

Comments have been disabled and we're not sure if we'll ever turn them back on. If you have something you would like to contribute, please send Justin an email or hit up social media!