Bad news is bad news again

Last Thursday, the media trumpeted the ASX’s latest all-time high with headlines like “ASX closes at record high on rate cut hopes”.

You see, any bad news – weaker jobs growth, slower growth – had become good news for markets, because it meant rates were more likely to come down sooner. In the article linked above, Jessica Amir, market strategist for trading platform moomoo, said that for Australian equities:

“[T]he bottom is behind us. We’ll probably continue to hit new record all-time highs for the rest of the year.”

But then something changed. A day after Amir’s call, the ASX200 fell 2.3%. Then on Monday it fell another 3.5%, for a cumulative decline of 5.7% in just two days. Amir is not quite in Irving Fisher territory – the great economist but poor investor infamously claimed that stock prices had reached “a permanently high plateau” just prior to the 1929 crash – but her timing sure was bad.

So what happened? Well, as usual it wasn’t just one factor but a series of events that set in motion the world’s largest rout for nearly two years, with implications for Australia and especially the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA).

Jobs, Japan and the R-word

Perhaps the biggest event was that the US economy finally received some really bad news: a disappointing July jobs report that triggered the dreaded Sahm Rule, which has predicted every US recession back to the early 1970s.

That was essentially the straw that broke the camel’s back for markets, which were already processing:

- underwhelming earnings reports from the Magnificent Seven;

- a call from the influential Goldman Sachs to raise its odds of a US recession in the next year to 25%; and

- the Bank of Japan’s (BOJ) decision to hike rates.

The most interesting and impactful of those was probably the last point. Now, normally a simple rate hike by a central bank wouldn’t be a big deal. But in this case, the BOJ triggered the reversal of some very popular carry trades (the act of borrowing in yen at low interest rates to buy in other markets with higher yields).

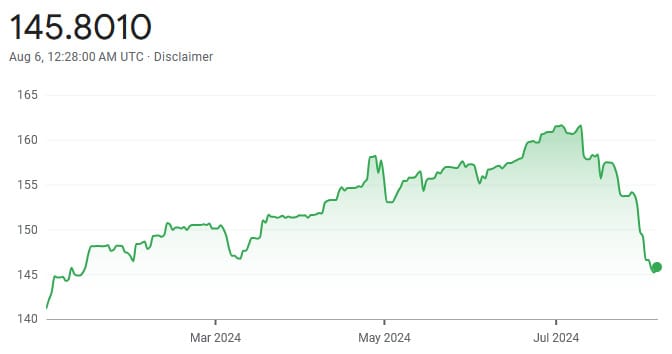

Basically, the rapid change in relative yields between Japan and other markets left investors scrambling to unwind their positions, which effectively forced them to buy the yen, driving up its relative price:

That also crushed the earnings outlook for large Japanese companies – which had benefited from a weak yen – and on top of liquidations (people really needed yen!), triggered the Nikkei’s worst daily loss in percentage terms since 1987.

As for the US jobs report, trouble has actually been brewing there for some time. Parker Ross, the chief economist of Arch Capital Group, warned that the US employment data have been “concerning” since at least December 2023, and that you may want to discount those saying that because economic indicators are all still looking OK, the recession risk is low:

“I’ve heard it argued that we shouldn’t be concerned about the decline in prime-age employment because it’s near a multi-decade high, but that’s also always been the case before prior recessions as well.”

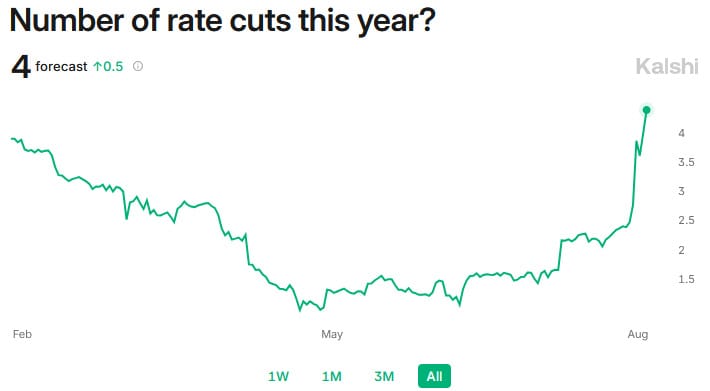

That fact was perhaps ‘realised’ after the jobs release, as US futures markets moved from pricing in a 90% chance of a 25 basis point cut in September to an 80% chance of a 50 basis point cut. Betting markets also reacted strongly:

So, in effect we had opposing forces working to trigger something of a doom spiral: a weaker US economy raised the odds that the US Fed would ease monetary policy, at the same time as the BOJ tightened more than expected. A huge speculative trade had been built on precisely the opposite forces, and nothing was spared as it unravelled:

“The spiking yen has, in turn, fuelled a stockmarket collapse. The rally had been led by Japan’s exporters, which benefit almost mechanically from a weaker currency, as they make most of their money overseas but report earnings in yen. Now they are suffering. Margin bets on Japanese stocks—trades made with borrowed money—had reached the highest level since 2006 before the sell-off began. These leveraged investments now appear to be being unwound at pace, explaining why market darlings are suffering some of the biggest falls.

…

Few analysts think Japanese firms are in deep distress, or fear for the stability of the country’s financial system. Nonetheless, rapid changes in Japan can have knock-on consequences. As interest-rate moves make the carry trade less viable, they could fuel a sell-off in far-flung corners of foreign markets.”

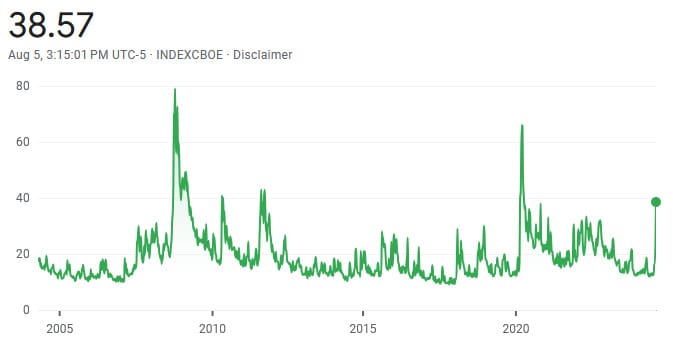

No one really knows what will happen as these speculative bets are unwound. The VIX, or Volatility Index, hit its highest level since the pandemic, and there’s inevitably going to be plenty of market gyrations as the uncertainty plays out – Japan’s Nikkei index promptly recovered around 10% yesterday.

The only thing I’ll add is that in times like this, it’s important to remember the adage that markets have predicted 9 out of the last 5 recessions. Markets do fall, sometimes by a lot, and after three days of carnage and a small recovery prices are about where they were three months ago.

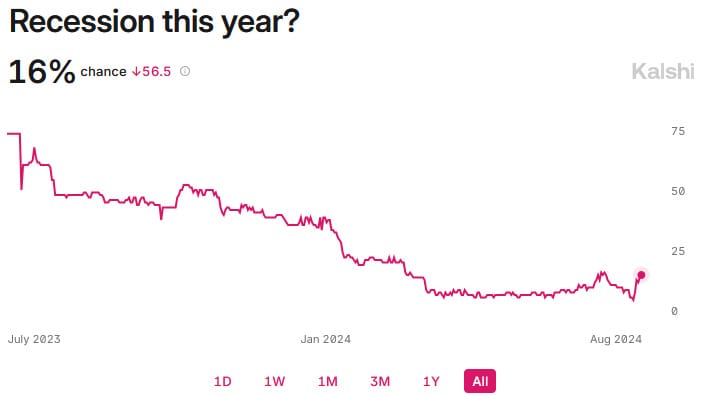

Will there be broader impacts? Probably not: people with skin in the game – punters – barely raised their recession odds for 2024 (with the caveat that there’s not yet a 2025 contract, which would probably tell us a lot more given the lags involved).

But what the chaos has brought to light is that global economies are weaker than first thought, and we might be moving to a cutting cycle soon than expected. Canada’s central bank has already cut rates, the eurozone has cut, the UK cut last week, and US markets have now fully priced in a September rate cut.

The big question is then: when might Australia follow suit?

Stuck between a rock and a hard place

The folks at the RBA would have breathed a sigh of relief last week after the June quarter consumer price index (CPI) figures came in roughly in-line with its May forecast. In fact, it was probably a bit lower than markets were expecting given that the Aussie dollar promptly dropped, reflecting that the odds of a rate hike also fell.

So, it was no surprises that yesterday it kept rates on hold and issued a relatively hawkish statement, warning about “higher public demand”, i.e. the strong fiscal spending by our various governments:

“Underlying inflation is forecast to return to the target range of 2–3 per cent in late 2025 and approach the midpoint in 2026. This is a slightly slower return to target than forecast in May and is due to greater inflationary pressures in the economy. In part, this owes to a stronger outlook for domestic demand, led by higher public demand and a recovery in household consumption as real disposable incomes and household wealth rise. But it also reflects the assessment that the economy’s capacity to meet this demand is less than previously thought.”

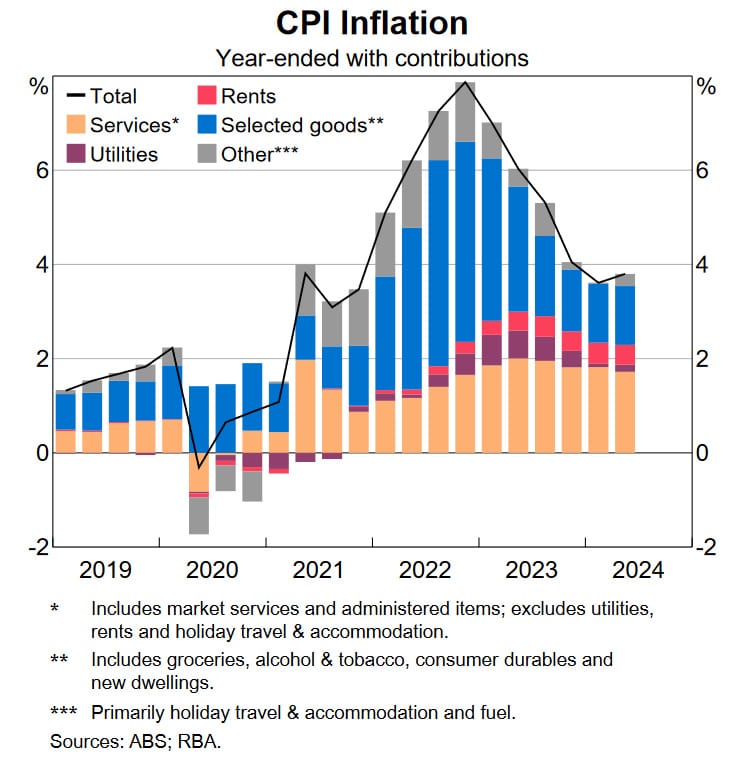

The RBA is right that demand has been strong and inflation’s sticky in Australia, especially in domestically-driven components such as services and non-tradables (orange bars below):

That’s largely the result of the RBA’s relative dovishness up to this point, or in its own words, an attempt to walk the “narrow path” between getting inflation down and not raising unemployment too much.

But an economy is in constant flux and that path moves. The cash rate that was appropriate a week ago may not be appropriate today, because of changes to the natural rate, which is the rate that doesn’t stimulate nor restrain demand.

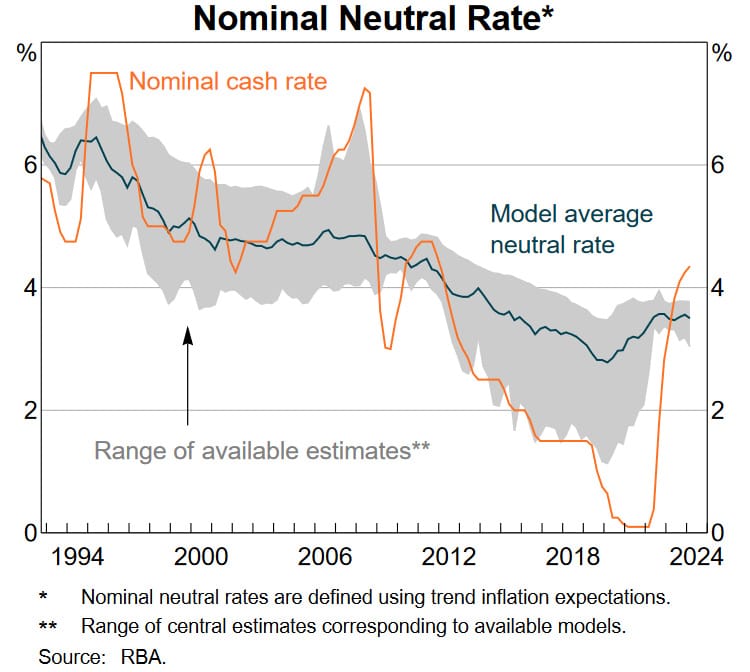

We can’t know what that rate is but there are a few approximations. The RBA produces an estimate – it calls it the ’neutral’ rate – and occasionally releases it publicly, as it did in this month’s statement:

The orange line is currently above the shaded area, so the RBA thinks monetary policy is already tight enough to bring demand back to within range. It’s very unlikely to raise rates further in such an environment.

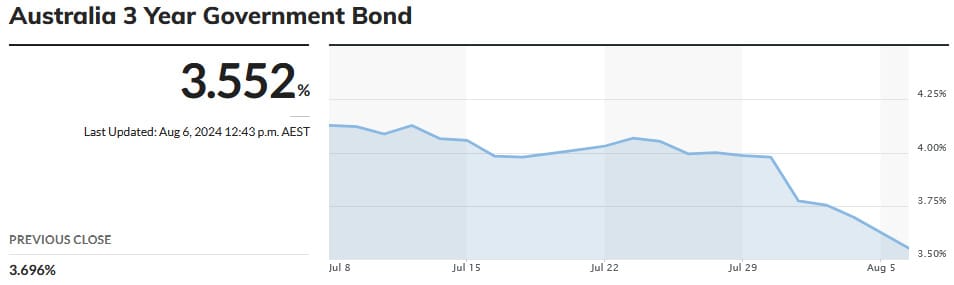

But the RBA won’t meet again for another seven weeks. While it was deciding what to do at yesterday’s meeting, markets shifted their expectations from no rate cut this year to a fully priced in 25-basis point rate cut by November. Additionally, the yield on 3-year Australian government bonds plunged more than 40 basis points in a week:

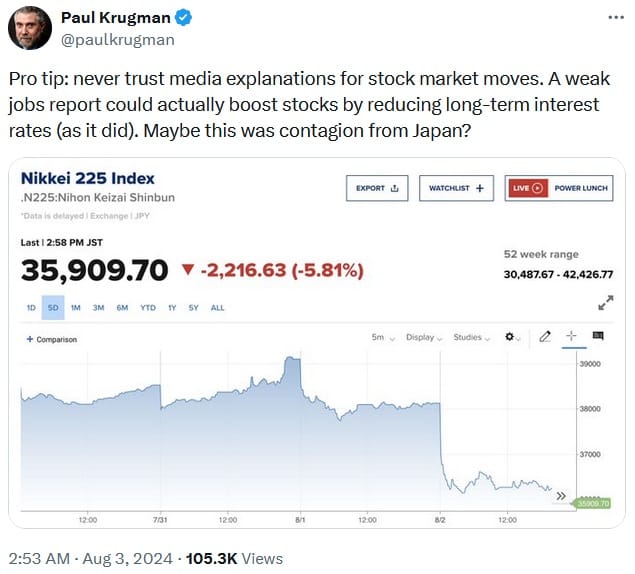

What does that all mean? The answer is that it depends on why rates fell. And this stuff isn’t easy; similar moves in US bond markets managed to confuse a Nobel laureate, who gave his followers what looks to be a really bad ‘pro tip’:

It’s a really bad take because a reduction in long-term interest rates tells us precisely nothing about whether it will be good or bad for stocks. Rates always change for a reason, and there was no deliberate action on the monetary policy front. So, depending on what that reason was, the change could be good or bad for stocks.

For example, are long-term rates falling because the market expects the Fed/RBA to have gotten on top of inflation, paving the way for monetary policy easing? That might boost stocks. Or did long-term rates fall because markets are increasingly pricing in an economic slowdown, so people are saving more now because they expect to be poorer in the future? That would be bad for stocks.

Given that long-term bond yields fell after the poor jobs report and during all the carnage, but before the RBA announced its decision yesterday (and days after the Fed’s decision), I’m inclined to think it’s more likely to be the latter.

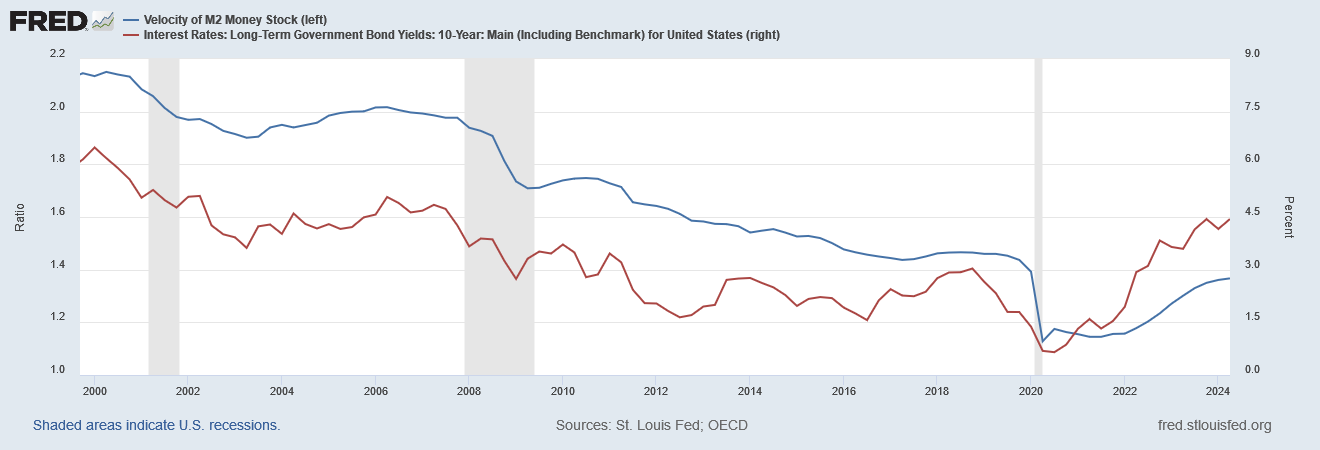

If so, that means monetary policy is probably quite a bit tighter now than it was even a week ago, because lower long-term rates in that scenario tend to mean lower money velocity (how frequently a dollar changes hand), which will also reduce aggregate demand (nominal GDP) without an offsetting increase in the money supply (e.g. through deliberate monetary easing).

Velocity tracks long-term interest rates reasonably well.

Velocity tracks long-term interest rates reasonably well.

If the market carnage washes through and long-term bond yields recover, there’s probably no harm, no foul; the fall in the natural rate was temporary.

But if long-term bond yields stay low or keep falling, then the RBA could very quickly find itself behind the curve, as it was when inflation first emerged – just in the other direction this time.

Death by data dependency

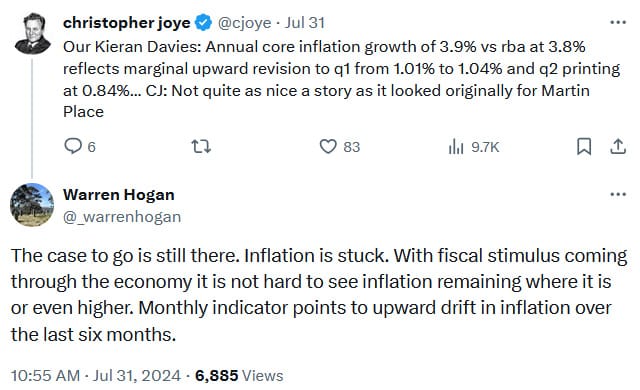

I’m worried about a recession in Australia because I suspect the RBA might be misreading the economic tea leaves. And it’s not alone; there are plenty of pundits out there still calling for rate hikes:

It’s true that the economic data are still displaying worrying signs for inflation. But a lot of those data are backwards looking. In fact, a good portion of today’s measured inflation is coming from goods and services where prices are government administered or indexed to past inflation, such as university fees, insurance premiums, alcohol and tobacco. Rents are another ‘sticky’ component, largely because of lags in how they flow through to the CPI:

“Rents on new leases flow through to CPI rents with a lag as only a small share of the stock of rental properties update leases in a given month, which implies that CPI rents inflation is likely to be high for some time.”

The RBA can’t do much about that. I mean, sure, it could tighten monetary policy even further, sucking the life out of the rest of the economy and triggering a recession, reducing inflation that way. But the reason these prices are sticky is because the RBA erred in taking so long to tighten in the first place (and stopped too early), allowing inflation – and expectations of future inflation – to get out of hand. That can’t be undone, other than with enough time or a painful recession.

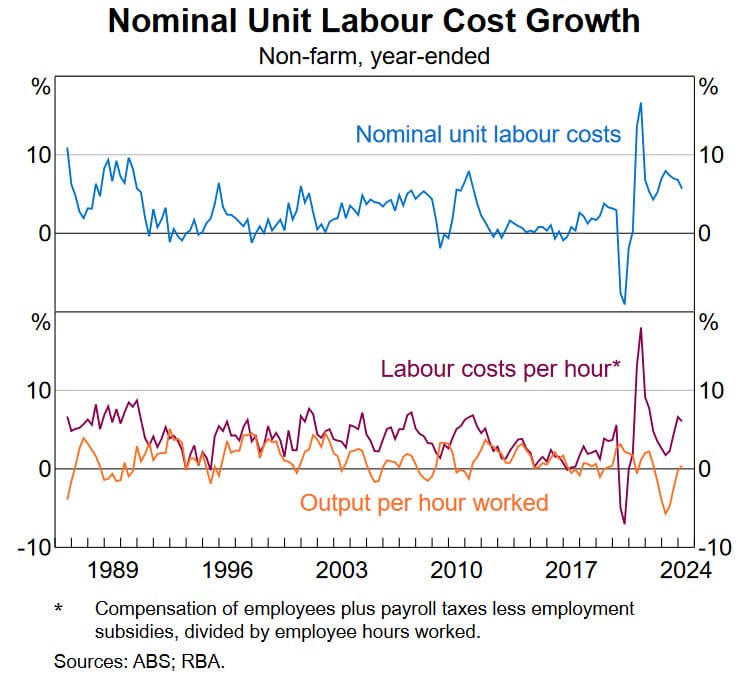

In my opinion, the real threat today is not inflation but stagflation. Unit labour costs – that is, labour costs adjusted by labour productivity – are growing at a very high 5.7% “over the year to the March quarter, well above its historical average pace”:

The RBA rightly worries that wages growing so much faster than productivity will make it difficult to get inflation “sustainably” back to its target. But it should also be worried about what the lack of productivity means for employment, the economy and growth.

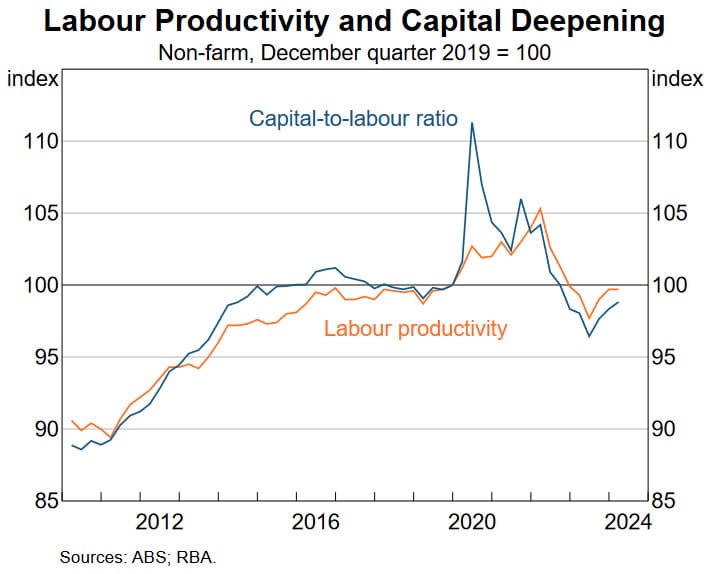

In the RBA’s statement, it dismissed those concerns by making the heroic assumption that we will see “a gradual increase in trend productivity towards its pre-pandemic rate”, rising from an expected 0.1% in the December quarter 2024 to nearly 2% by June 2025, then continuing to grow at a rate above 1% annually for evermore. A tall order considering that productivity has gone backwards for years!

But you can’t just magic up productivity; other than another lucky mining boom, productivity growth requires a conscious effort from our governments to make positive policy decisions that can take years to bear fruit, as opposed to the temporary sugar rushes they can provide with debt-financed “cost of living” handouts. And I’m just not seeing that – or at least not enough to get labour productivity growing consistently above 1% annually, anyway.

If we don’t get the productivity the RBA is forecasting, then we’re basically facing a real shock, in part because of lagged inflation: nearly 60% of wages are set by award or collective agreement in Australia, by bodies that tend to look at the year just gone when setting them. That means labour costs will continue rising into a stagnant economy, and without productivity improvements, businesses may have to start shedding workers.

Unfortunately, there isn’t much the RBA can do to fix such an outcome. It can make it worse if it keeps monetary policy too tight for too long (i.e., above the natural rate), and it may well fall into that trap given there’s probably at least several months of ‘sticky’ inflation left to flow through the aggregates and they don’t meet for seven long weeks, during which the current cash rate could quickly become inappropriate.

It’s clear that the RBA doesn’t want to repeat the mistakes it made letting inflation get out of control. In the post-decision press conference, governor Bullock said that market pricing of rate cuts this year “doesn’t align” with the RBA’s thinking, and that “we are data dependent”.

But often, being data dependent – especially when those data are things like the national accounts or CPI – only guarantees that your action will be too late. I worry that the RBA hasn’t learned all that much from the past few years, and by stubbornly trying to fix its last mistake, has opened itself up to making the same mistake in the other direction by maintaining a too-tight monetary policy for too long.

Comments

Comments have been disabled and we're not sure if we'll ever turn them back on. If you have something you would like to contribute, please send Justin an email or hit up social media!