Barriers to nuclear, the tradie shortage, trade-offs still matter, the deal of the century, and don't fire the bureaucrats

For whatever reason I’ve read more than the usual amount of interesting content over the past week, so here’s another post replete with my thoughts on several topical issues.

Nuclear is easier said than done

In somewhat of a cautionary tale for Peter Dutton’s nuclear ambitions (should he win the election), the most important piece of the puzzle may well be how his government chooses to regulate it. Specifically, he should distinguish between large- and small-scale reactors, to avoid stifling innovation in small plants that post significantly less risk to the public:

“Small scale nuclear should be regulated like x-Ray machines or gas turbines not like billion dollar nuclear power plants, the current rule [in the USA]. Reasonable regulation will allow iterative innovation. As I said in my post Give Innovation a Chance, innovation is a dynamic process. You must build to build better.”

That’s from economist Alex Tabarrok, who quoted the following passage that highlights just how difficult it is for small modular reactors to get up in the US:

“The licensing process alone can take up to nine years. Small modular reactor company NuScale spent more than $500 million just to get its design certification approved by the NRC, a process that took more than two million hours of labour and required millions of pages of information. NuScale still needs to apply for its license, which will multiply these costs.”

NuScale was the example used by Australia’s CSIRO in its 2023-24 GenCost report to dismiss the technology as the most expensive available. While that is technically the truth, it also shows that reports like GenCost are static in nature, and fail to account for the fact that “innovation is a dynamic process” and regulatory barriers that are driving up costs today might come down tomorrow.

Australia’s tradie shortage

For many years, Australian governments have been pushing for more and more students to go to university, which makes sense: a well-educated, highly skilled workforce is generally a good thing for a services-heavy economy. The 2024 Australian Universities Accord even has “a tertiary qualification attainment target of 80% of the working age population by 2050”.

The Accord defines a tertiary qualification as a Certificate III or above, which includes courses in specialities like Early Childhood Education, Individual Support, Aged Care, Health Administration, Business Administration, Community Services, Security Operations, and Pathology Collection.

It’s a long list and basically includes everything except trades. But that might be a problem; as with most things, there are diminishing returns to tertiary education, and as a country we may not want 80% of our workforce in these sectors. That’s because we also need lots of electricians, plumbers, chippies, etc – in fact, those are precisely the kind of workers that Jobs and Skills Australia claims we’re most short of:

“Shortages were most common for Technicians and Trades Workers, with 50% of occupations in the category assessed as being in national shortage, broadly consistent with findings of previous Skills Priority Lists. For example, all occupations in the Construction Trades Workers and Food Trades Workers groups were found to be in national shortage.”

Despite strong population growth Australia actually lost tradies in 2024:

“Australia had 27,000 fewer tradies last year than in 2023 and the alarming revelation has prompted major warnings from industry experts. The federal government’s ambitious goal of building 1.2 million homes over a five-year period could be in serious doubt if construction sites aren’t able to bring in the next generation of tradespeople.”

Why be a tradie when the government is throwing money at you to attend tertiary education so that it can attain its 80% target, whether through the recent HECS changes or ‘fee free TAFE’ courses? And even if that’s not enough, there’s always construction:

“Veteran builder Scott Challen told Yahoo Finance that it’s no wonder apprentices are dropping out in their thousands.

‘We need to bring in more incentives for apprentices, which means increasing the apprentice wage subsidy,’ he said.

‘We’ve got to look at junior pay rates in the construction industry and try and get them sorted out, because I can’t have a 17-year-old apprentice on $17 an hour and a 17-year-old labourer on $32 an hour. It doesn’t make sense to these kids’.”

Not everyone is equal. By subsidising tertiary education, the marginal student – who may previously have gone into a trade – has been lured away from completing an apprenticeship and into a Certificate III.

In response, the industry is trying to ‘pull’ manual labourers up from construction and into those now-vacant apprenticeships, but they simply can’t compete with the wages on offer. Or perhaps those construction workers were ill-suited to a trade anyway and wouldn’t complete one no matter how generous the subsidy.

Either way, there are trade-offs involved when governments set arbitrary targets like an 80% tertiary attainment. There’s no way to know what the optimal share of the working population with a tertiary education should be, but if the price (wages) of tradies continues to rise, that’s a pretty good signal that we’ve gone too far.

Blind to trade-offs

Speaking of trade-offs, Harvard’s Jason Furman penned an interesting opinion piece last week that took aim at politicians from both the left and right:

“The liberal [left-wing] vice is thinking that all good things go together. Every progressive goal will simultaneously boost economic growth and create jobs. Any lockdown that prevented Covid’s spread helped the economy. Environmental regulations create green jobs while reducing emissions. Child-care requirements and hiring preferences help microchip production.

The conservative vice is arguing that costs are so catastrophically large that other policy goals don’t merit consideration. Any Covid social-distancing measure killed jobs. Any carbon regulation destroys growth. Any tax increase devastates the economy.”

The great Thomas Sowell likes to say that “there are no solutions, only trade-offs”. Furman argues that both sides of politics have failed to heed that warning:

“Sufferers from the liberal vice get the signs wrong about trade-offs. They think raising the minimum wage increases employment without even minor bad side effects in terms of benefits, training or anything else. Sufferers from the conservative vice get the magnitude wrong, arguing that even modest increases in the minimum wage will cause massive job loss.

Each vice leads to a failure to take trade-offs seriously. Liberals do benefit-only analysis in which everything passes because all good things go together. Conservatives do cost-only analysis in which everything fails because economic effects dwarf all other considerations. In both cases, economic analysis becomes propaganda for predetermined conclusions rather than a tool for making difficult choices.”

Australia’s federal politicians have just entered election mode (for those in WA, state politicians too!), which means politicians will be even more likely to pretend that trade-offs don’t exist and that their policies will bring nothing but benefits (and their opponents’ nothing but costs).

The deal of the century?

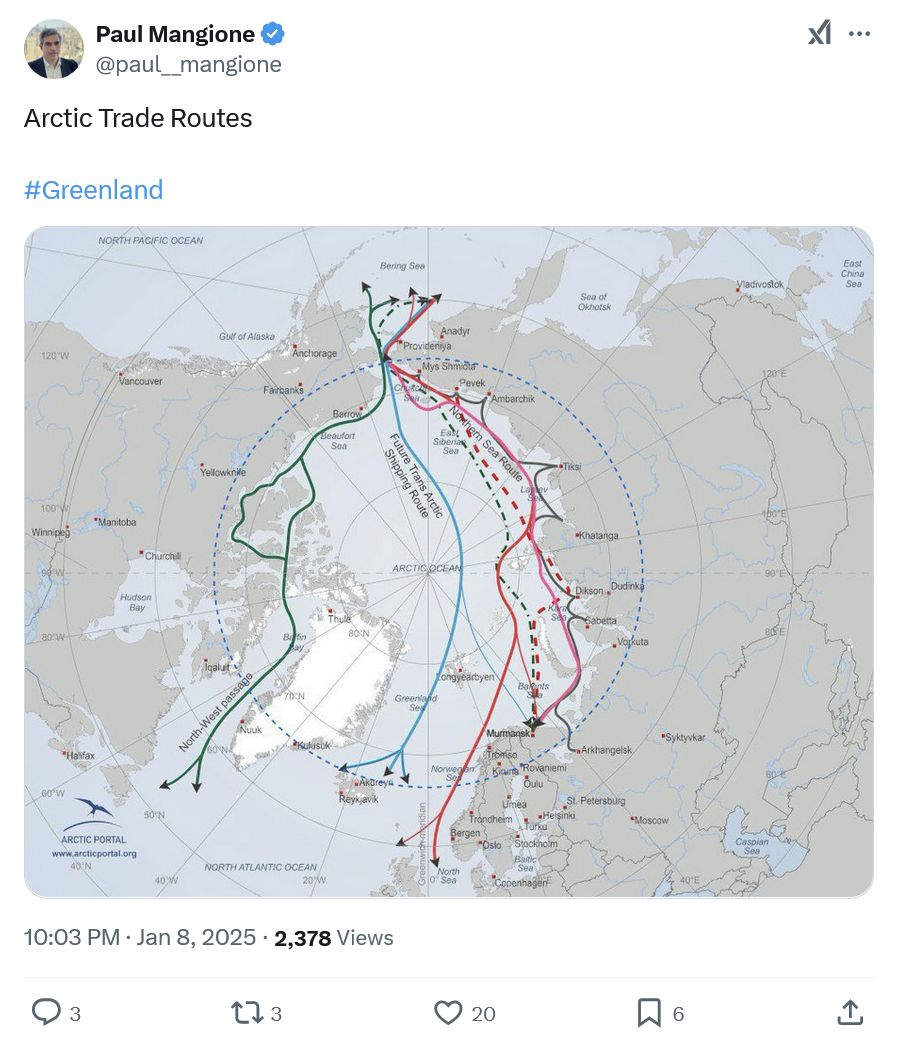

Donald Trump wants Greenland to become part of the US, even if he has to use the military to do it. Many people have speculated as to why, positing reasons from gaining strategic access to thawing Arctic channels, to wanting to lock up natural resources that may or may not exist in its vast tundra.

Personally, I put it down to Trump’s obsession with a period of American history – specifically the late 1800s, a time when President Andrew Johnson purchased Alaska, and President William McKinley passed the infamous McKinley tariffs (which, if Trump was familiar with history, should in fact discourage him from using tariffs).

But with Trump, who really knows. The real question is then – would it be a good deal? The Economist certainly thinks so:

“The island sits between America and Russia in a part of the world that is becoming more navigable as Arctic ice melts. Although America’s Pituffik Space Base on the territory’s north-west coast already provides the armed forces with missile-warning sensors, an American Greenland might better monitor the Greenland-Iceland-UK (GIUK) gap, a strip of the Atlantic Ocean that is the access route for Russian submarines to America’s east coast, and to the North Atlantic.

On top of this, Greenland’s resource wealth is immense. It has known reserves of 43 of the 50 minerals deemed ‘critical’ by America’s government, including probably the largest deposits of rare earths outside China. These are crucial to military kit and green-energy equipment. Wells off Greenland’s coast could yield 52bn barrels of oil, about 3% of the world’s proven reserves, according to an estimate in 2008 by the US Geological Survey.”

Greenland is only home to around 56,000 people, so the Trump could probably ‘persuade’ them with a one-off payment of $1 million per inhabitant – a “crude valuation of the flow of future taxes” – which is the equivalent to just 5% of the US annual defence budget.

And he might be on to something. Greenland’s Prime Minister Mute Egede said “we are ready to talk”, and an “independence movement has gained momentum in recent years”.

Whether “independence” includes ditching the Danes and moving under the protection of the US, perhaps as an unincorporated territory like the US Virgin Islands which were also purchased from Denmark in 1917, remains to be seen.

Don’t fire the bureaucrats

Elon Musk and Vivek Ramaswamy will soon head the US Department of Government Efficiency, tasked with slashing trillion dollars of federal spending. Ramaswamy has previously suggested this could be done by instantly firing 50% of federal bureaucrats, or around 1.5 million people (~0.85% of the total US workforce), at random.

Writing over at Astral Codex Ten, health professional Scott Alexander doesn’t think it’ll be that easy. The example he uses is from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA):

“Maybe he is working off a thesis where red tape expands to consume the resources available to it (as measured in bureaucrats). But my impression is that the amount of red tape is determined more by things like:

— How likely is it that their decision will get challenged in court?

And if it gets challenged in court, what amount of paperwork do they have to show the judge to prove that they made the decision on a ‘reasonable basis’?”

Basically, Alexander worries that in the litigious US a key reason why bureaucracies take so long to make decisions is because they get sued for doing anything. In such an environment, cutting bureaucrats could be counterproductive:

“If you cut their bureaucrats in half, that doesn’t mean there will be fewer steps in the process. It means they’ll keep wanting not to get sued, the process will stay the same, and everything will take twice as long.

…

[I]f you cripple bureaucracies’ ability to interact with these fields, it doesn’t mean they’re fully legal, free, and happy forever. It means they’re stuck in regulatory limbo.”

This is certainly true in Australia, too. For example, in NSW “the number of development applications referred to the court had more than doubled in the last decade – despite the number of judges never increasing since the court was established in 1980”.

If you don’t cut red tape, you might actually need more bureaucrats for anything to get done in a timely manner. But cutting regulation is much more difficult than sacking half of the country’s bureaucrats with the flip of a coin; Musk and Ramaswamy have their work cut out for them!

Fun fact

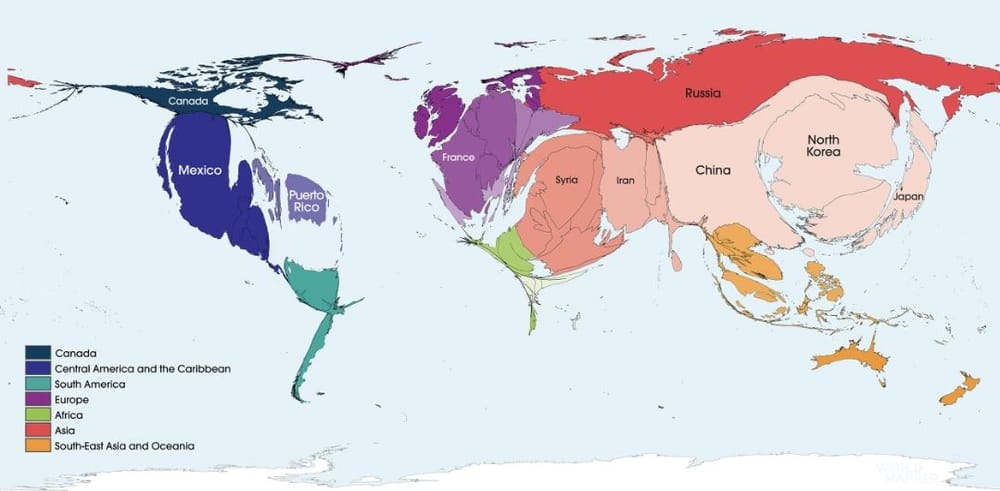

How often Donald Trump has mentioned other countries (excluding the US).

Australia’s doing a good job of flying under the radar!

Further reading

- The Victorian government will “slash the minimum amount that energy retailers must pay to household customers [for solar feed-in] by 99 per cent”. This is an inevitable consequence of a renewables-heavy grid; the next step is to transition everyone onto time-of-use plans, and allow households to get paid for supplying power during high-demand periods.

- Stricter worker classification laws, such as those that require gig workers to become employees, " caused significant declines in traditional employment, self-employment, and overall employment" in the US.

- A new paper by Harvard’s Ed Glaeser found that local zoning laws reduced the size of projects, allowing smaller construction companies to proliferate “reducing both scale economies and incentives to invest in innovation”, thereby causing construction productivity to stagnate (smaller builders are less productive).

- Why have fertility rates fallen? “When societies enjoy a sustained period of wealth, birth rates tend to decline thereafter.” But why? It’s not economic growth, which is correlated with higher fertility. Demographer Lyman Stone reckons that in rich countries, it’s " primarily due to delayed marriage and coupling". That then became embedded in Western culture, and spread to other countries “regardless of if they actually get rich”.

Comments

Comments have been disabled and we're not sure if we'll ever turn them back on. If you have something you would like to contribute, please send Justin an email or hit up social media!