Blowing the boom, eurosclerosis, China's decline, why Nvidia is American, beware the dunkelflaute, limits to AI, and the brain drain

Most readers of Aussienomics are probably still busy soaking up the Australian summer rather than looking for interesting tidbits in their inboxes. But for those of you still checking your emails, here are a few of my thoughts on some of the essays, papers and news I’ve read over the break.

Higher taxes, less spending, or more inflation

I usually like to kick these emails off with an Australian story, and while content has been light with everyone on holiday, the AFR’s John Kehoe didn’t disappoint with a recent feature on how the “lucky country has blown the (20-year) boom”:

“The windfall to governments over two decades would be hundreds of billions of dollars. But Australian governments have blown much of the windfall from the mining boom, which may now be approaching an end as China’s economy slows.

…

The bottom line is that spending is permanently higher, debt has blown out, real wages and productivity growth are weak, and despite the extraordinary quarter-century boom, Australia faces a decade of deficits.

Furthermore, just months out from a federal election neither political party has a substantial plan to deal with this reality, even as leading economists agree that spending cuts or tax rises will eventually be inevitable.”

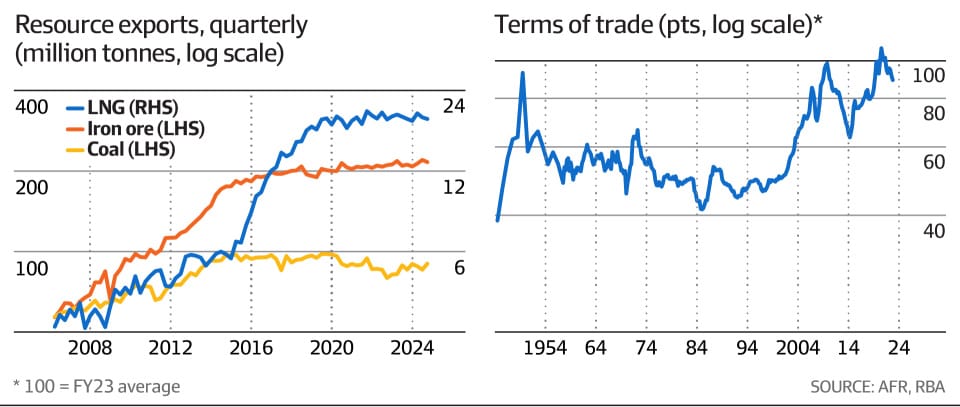

The boom in chart form:

I’ve been saying more or less the same for a long time. It’s also why federal and state government spending has suddenly made inflation worse: expectations matter for inflation, and without a credible plan to pay for the permanent increase in spending – future surpluses of tax revenue greater than spending – people will expect some of it to be inflated away.

Basically, people change their behaviour today based on their expectations of the future, and at the margin they buy more stuff and demand fewer dollars (or equivalent, e.g. bonds) than they otherwise would have, pushing up the price level, devaluing the government’s debt to match what people expect to be repaid. The inflation eventually goes away on its own, unless the government responds with even more spending (e.g. by never fixing its underlying fiscal problems).

There’s no China Two on the horizon this time. Australia desperately needs fiscal (i.e. tax) reform, along with microeconomic (e.g. regulatory) reform, to revive productivity.

That, or we’ll end up like the Europeans.

Europe’s worsening malaise

Economist Scott Sumner recently published an essay on the “European Malaise”, or the huge and growing productivity gap between European nations and the US. Reforms in the 1970s and 80s levelled the playing field a bit, but since the 2010s the state has again become all-consuming in many countries, typified by the lack of entrepreneurship in Europe:

Or by France and its recent electoral chaos:

“France is obviously spending too much (57% of GDP). No one can convince me that the French public could not get by just fine with a Swedish-sized welfare state, spending 49% of GDP. (And IMF data suggests that both Denmark (45%) and Norway (39%) have even lower spending.)

So why don’t they fix the problem? As always, economics is downstream of politics, and politics is downstream of culture. French politics is in a sort of death spiral. Each election sees the far right gain more strength, and every attempt to fix their economic problems makes the right even stronger.”

Sumner doesn’t think a shift to the right will actually help, though, because people like Le Pen “are big government statists. They are both nationalistic and mildly socialist”.

France’s “polarised system” gives its people few options to restrain public spending, while “Sweden’s political system seems to have enough cohesion that they were able to pull back from the fiscal abyss”.

Ultimately, there’s no single explanation for the worsening malaise. But Sumner suspects that “big government naturally gets less effective over time”, as witnessed in Communist countries and poorly run, big government cities in the US (e.g. “downstate Illinois, upstate New York, and California’s Central Valley”).

In other words, don’t get complacent.

There’s no China Two

Blogger Noah Smith published a good post on the Chinese economy on the weekend. If find his work better better when writing about non-American issues, which tend to be influenced by his tribal Democrat-first, economics-second ideology.

In his post, Smith notes that the forces that helped create the first Chinese economic boom – liberalisation, favourable demographics, urbanisation, technological catch-up, and global export markets large enough to absorb its growing production – either no longer exist, or are greatly diminished. Put them together with President Xi Jinping’s infatuation with a unique style of industrial policy, and the government’s determination to avoid a recession at all costs, and it has decimated Chinese productivity growth.

Here’s Smith on recession-busting, China style (the 2008-09 stimulus was just prior to Xi’s ascent to power):

“The Chinese government, eager to preserve the appearance of invincibility, often goes overboard in unleashing the tools of control. But while recessions are not healthy things, the lengths to which Chinese policymakers went to make absolutely 100% sure they never had even the slightest recession may have left their economy with a huge hangover of low-productivity industry.”

And on industrial policy, Xi style:

“Essentially, Xi is trying to crush industries he doesn’t like, in the hopes that resources — talent and capital — flow to the industries he does like. This is a new kind of industrial policy — instead of ‘picking winners’, Xi is stomping losers.

…

But it’s far from clear that an economy works like a tube of toothpaste, where smashing one end will send resources squirting out the other end. If you’re a budding entrepreneur, do you really think that starting a semiconductor company instead of an internet company will win you Emperor Xi’s favour? What if next week he decides that he doesn’t need more chip companies, and that your company isn’t one of his preferred champions? What if after you get rich and successful, Xi decides you’re a potential rival and appropriates your fortune?

An economy where the leader is always smashing companies and industries he doesn’t like is inherently an economy full of risk. Yes, Chinese engineers and managers will obey Xi’s will and go into the industries he wants them to go into. But the loss of entrepreneurship and initiative might make this a pyrrhic victory.”

What Smith misses is that all industrial policy, if allowed to scale – even the subsidy-based “picking winners” version he favours – works this way. To repeat what I wrote a couple of weeks ago:

“The larger the government and the more industries in which it directly meddles increases the opportunities for politicians to hand out favours, and for businesses to feel forced to bend the knee if they wish to prosper.”

China still has the fiscal capacity to postpone an inevitable period of mediocre growth driven by policies of the past that badly misallocated its stock of capital and labour. If it eventually takes that option, it will provide another short-term fiscal boost for Australia. But any stimulus will be shorter and less impactful than those of the past, with an even greater price to be paid when it eventually peters out.

What if Nvidia didn’t exist

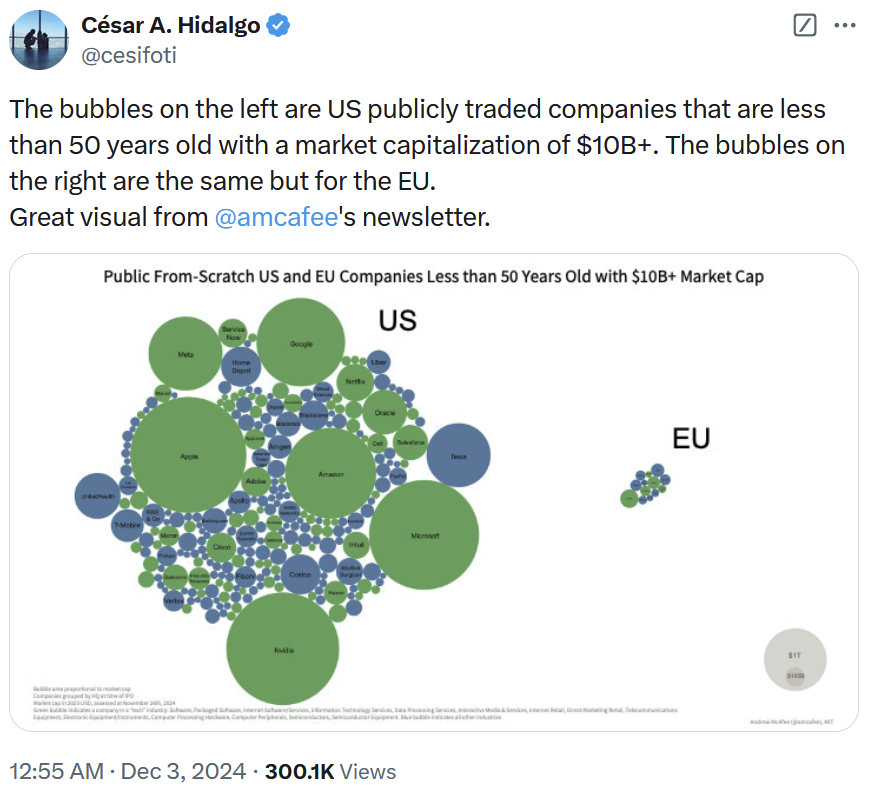

This is more of a fun fact but fits in nicely with the above section on Europe:

There’s a reason why artificial intelligence emerged in the US and not Europe, and why an American company with a Taiwanese founder – Nvidia – was there to profit from it. Talent goes where it’s wanted, and rarely is that place in Europe.

Fun fact

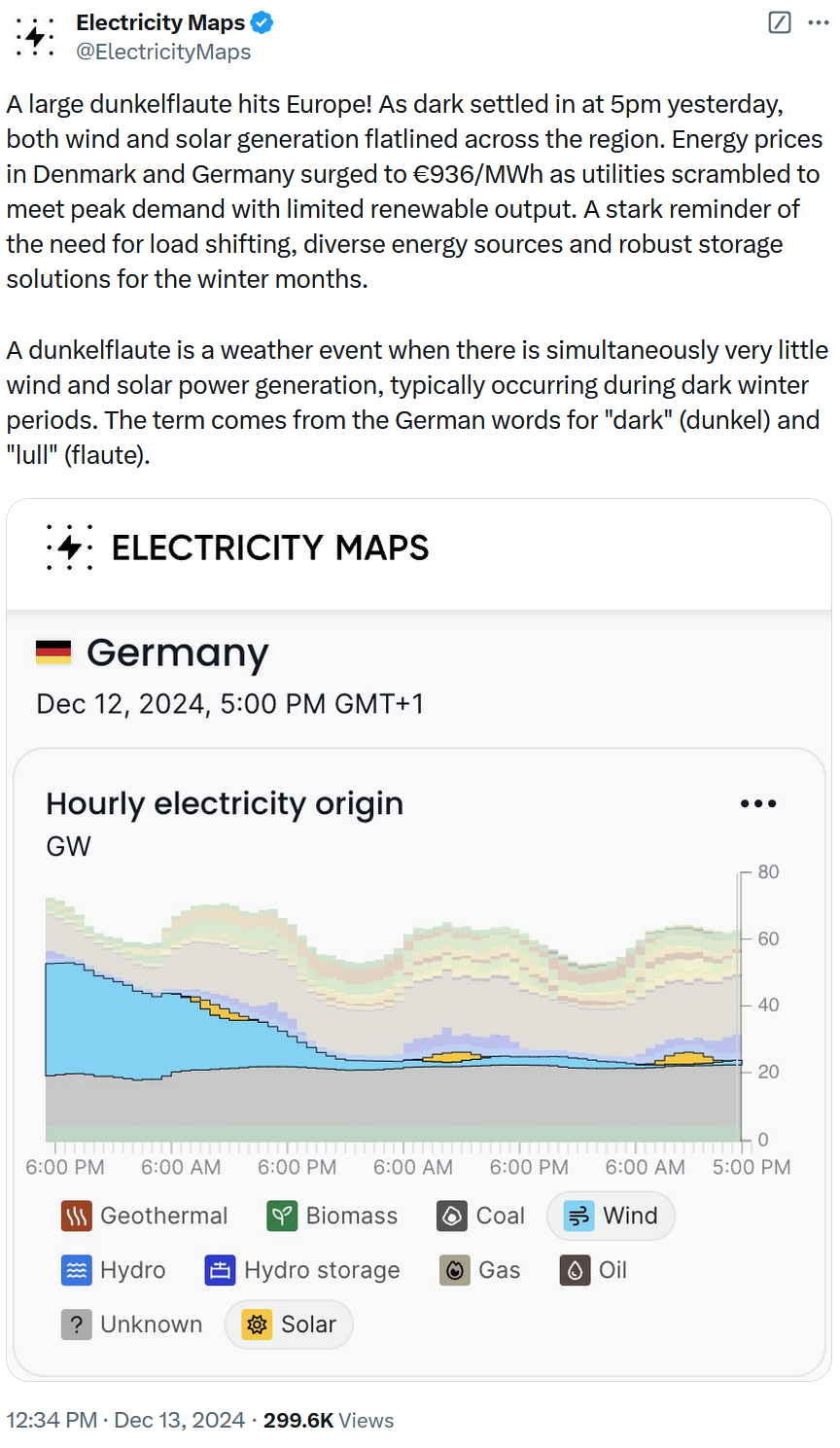

Beware the dunkelflaute (anticyclonic gloom) in a renewables-heavy energy market:

During the period charted above spot energy prices spiked by nearly 800% across Europe, leading Scandinavian countries with larger amounts of baseload people (e.g. nuclear) to “consider cutting shared-energy links” and:

“Sweden’s energy minister Ebba Busch said she was only open to a new underwater cable connection to Germany if Germany rejigs its electricity market to protect Swedish consumers and their access to cheap homegrown energy.”

Unlike Germany and Denmark – where by 2034 it’s expected to only have sufficient domestic production “to cover around 25-40% of its [peak time] consumption” – Australia has no neighbours from whom it can bid energy if the wind stops blowing on a cloudy day.

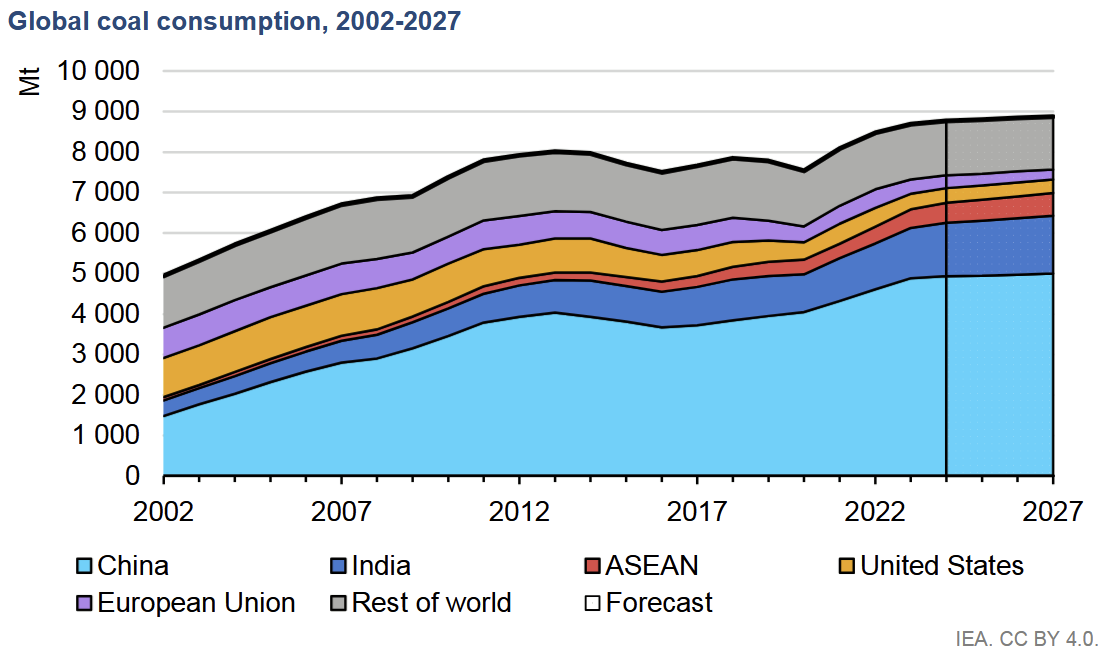

On separate note, the International Energy Agency’s latest report now expects Chinese and Indian coal consumption to continue rising through to 2027 (as far as its forecasts go), after a big increase in 2023:

“China, the world’s largest coal consumer, accounted for over 56% of global demand in 2023. The country’s coal consumption increased by 6% to 4,883 Mt, with the power sector accounting for 63% of its coal demand. India, the second-largest consumer, saw a 10% rise in coal demand, reaching a total of 1,245 Mt.”

Your friendly reminded that emissions matter on a global, not local, basis, and if we can’t guarantee that renewables will keep the factories running, the lights on, and the AC blowing, then perhaps burning gas and coal until battery prices become more economic isn’t the worst thing in the world. Especially when the average Australian is only willing to pay $200 to avoid climate change.

The limits of AI

Harvard’s Cass Sunstein has an interesting draft paper using Knightian and Hayekian insights to demonstrate the limits to AI. Basically, AI’s are trained on the past which isn’t much good for predicting the future, given uncertainty, the knowledge problem, and “the unfathomably large number of factors that account for some kinds of outcomes and the critical importance of social interactions”:

“There are some prediction problems on which AI will not do well; the reason lies in an absence of adequate data, and in a sense in what we might see as the intrinsic unpredictability of (some) human affairs. I have referred to disparate challenges, but all of them are closely connected to the knowledge problem, and in particular to the unfathomably large number of factors that account for some kinds of outcomes and the critical importance of social interactions.

In some cases, AI will be able to make progress over time. But in important cases, we are dealing with complex phenomena, and the real problem is that the relevant data are simply not available in advance, which is why accurate predictions are impossible – not now, and not in the future.”

That’s not a problem unique to AI; humans suffer from the same constraints. But it does mean that AI will forever be limited in its ability to make forecasts, or to organise society as if it were some grand, omniscient central planner.

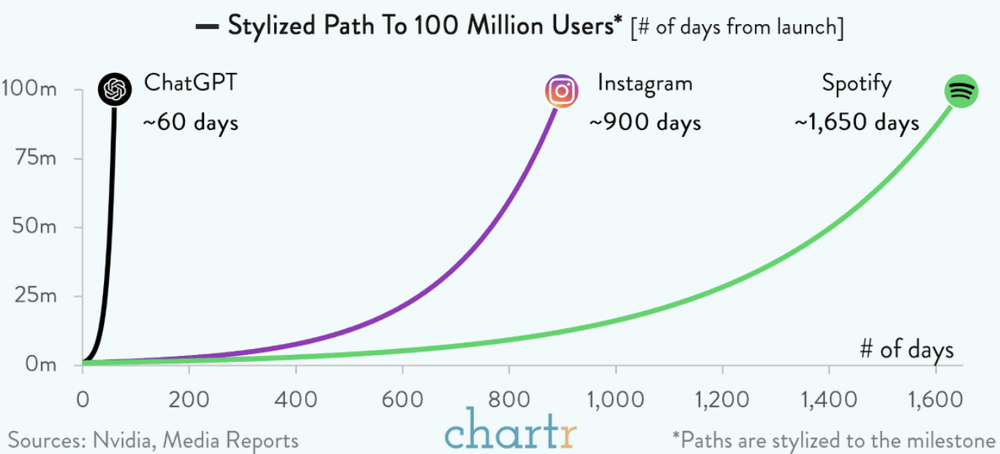

But that doesn’t mean AI won’t be the most useful technology invented for some time. Just look at the uptake:

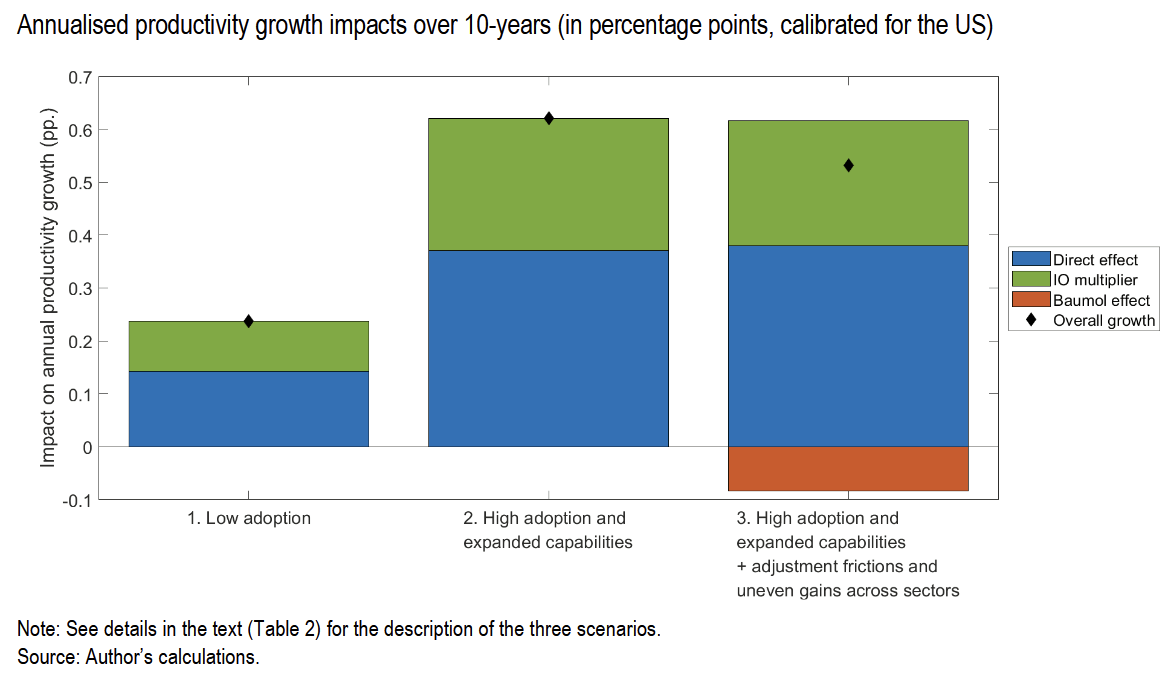

AI might also enable “problem solving at scale”, or help to revive lacklustre productivity growth in countries that have become allergic to reform:

But those gains will only materialise if governments ensure to “enable fast and widespread adoption in places where AI can make a positive impact on productivity and thereby improve societal well-being”.

Basically, don’t be Europe:

“The limited ICT-related gains in Europe are often ascribed to an adoption challenge (less successful integration of digital tools in sectors with strong potential for ICT gains, such as retail), combined with stronger impediments to within sector reallocation in Europe.”

Protect workers, not jobs.

Beware the brain drain

A third of Australians now work from home (WFH) “on a regular basis”, yet 82% of Australian executives “expect a full return to the office within the next three years”.

I’ve written before about the many benefits to WFH, and that the practice might even explain why wage growth has been relatively subdued.

Now there’s another new paper showing that if you’re an executive who wants to force people back into the office, then you had better beware of the ensuing brain drain:

“We find that these RTO [return to office] firms experience higher employee turnover rates after announcing RTO mandates… We further find that female employees, more senior employees, and employees with higher skill levels are more likely to leave RTO firms… our evidence suggests that RTO mandates are costly to firms and have serious negative effects on the workforce.”

Have a great day and a Happy New Year!

Comments

Comments have been disabled and we're not sure if we'll ever turn them back on. If you have something you would like to contribute, please send Justin an email or hit up social media!