Can we fix housing?

I don’t think anyone would disagree with the claim that housing is expensive in Australia. It’s when you start talking about why that you run head-first into a debate, with everyone having their own scapegoats from “greedy” developers on the left to unchecked migration on the right.

Or if you’re the ABC’s Alan Kohler, it’s because John Howard cut the capital gains tax in 1999. Ah, if only Australian tax policy were so influential to also affect housing prices in most other developed economies!

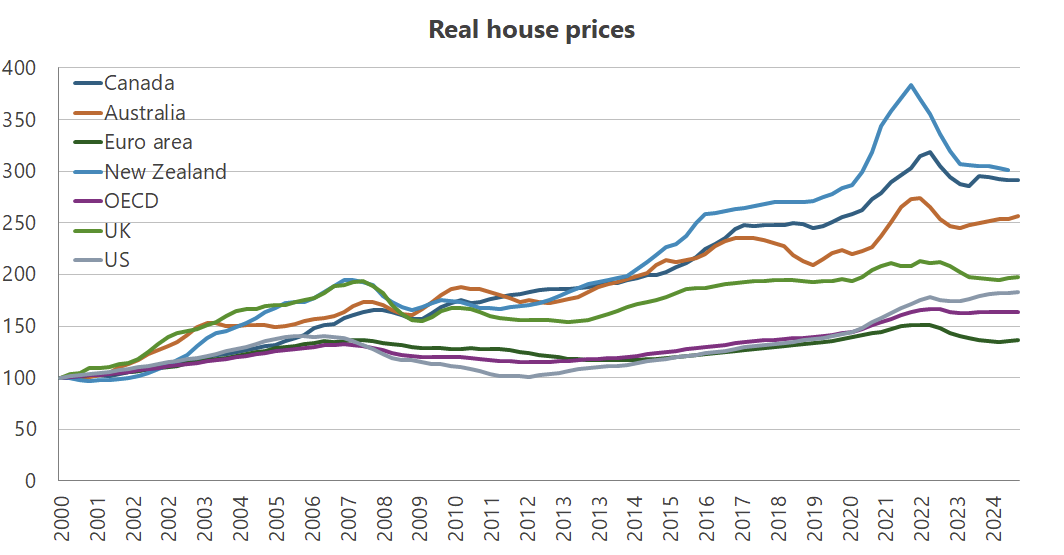

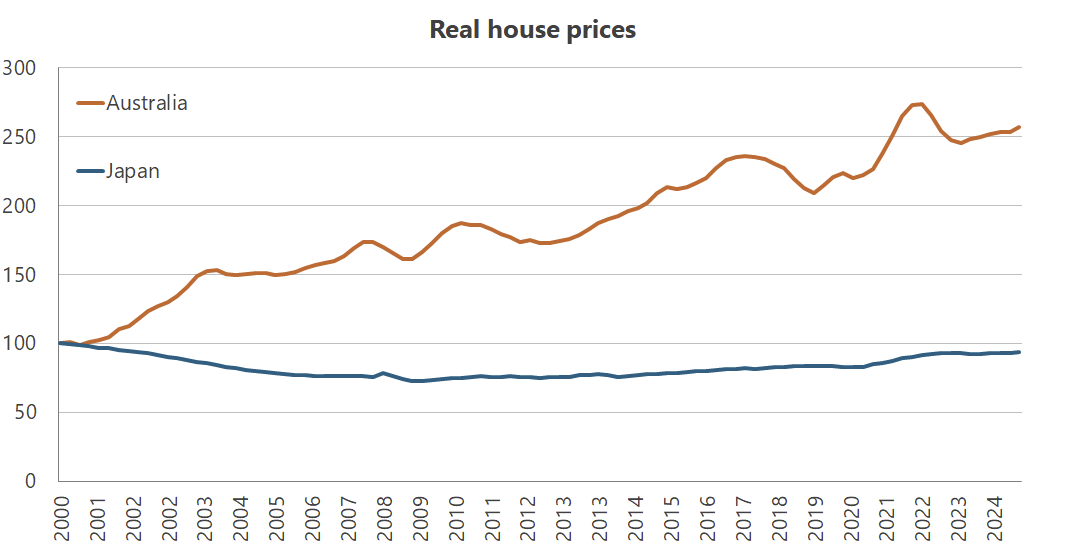

No, the reason housing has become expensive in Australia – and in the other countries shown in the chart above – is because of deliberate policy trade-offs made by their respective governments.

At least that’s what the Productivity Commission (PC) found in a new, comprehensive report on construction productivity, humorously titled Can we fix it?

Not just an Australian problem

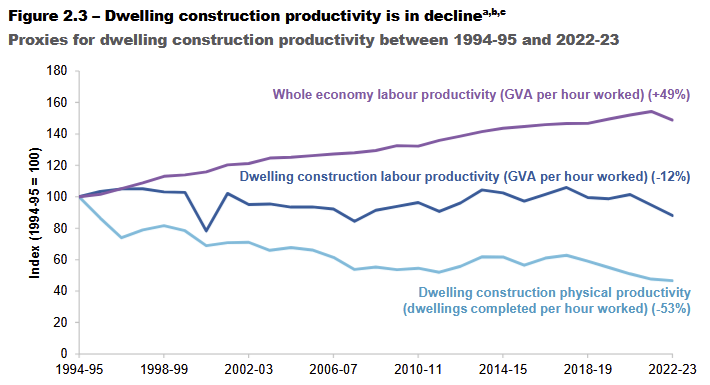

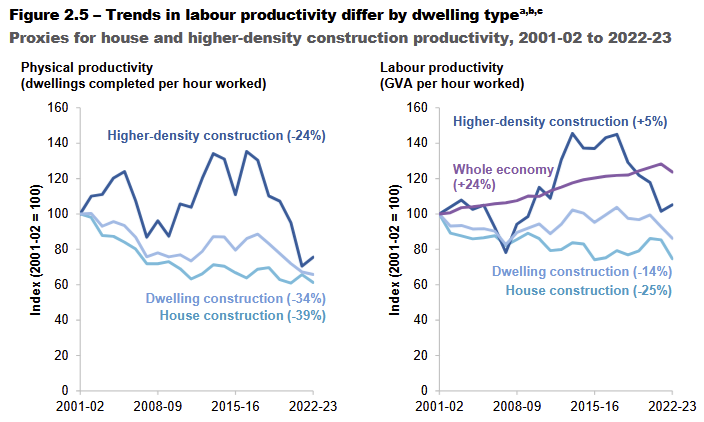

According to the PC, not only has construction productivity in Australia performed much worse than overall productivity over the last 30 years, it has actually declined:

- The number of new dwellings built per hour worked has declined 53%.

- Dwelling construction gross value added per hour has declined 12%.

And one major consequence of poor construction productivity is less affordable housing, given that Australians spend $80 billion each year on new housing.

I’ve long been interested in this topic, but the Australian data have been… non-existent. Harvard’s Ed Glaeser has documented the stagnation of construction productivity in the US, finding that:

- local land-use controls limit the size of projects; which

- also reduces “both scale economies and incentives to invest in innovation”; so

- you end up with a bunch of smaller, less productive builders.

Glaeser and his co-authors estimate that construction productivity in the US would be around 60% higher if the size distribution of construction firms matched that of manufacturing.

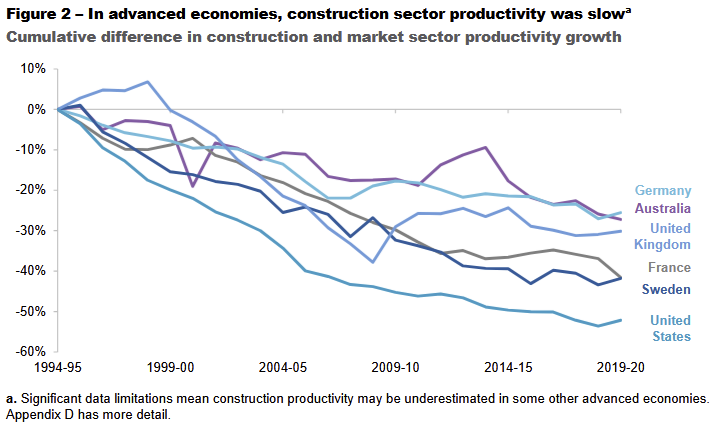

So, what about Australia? The PC noted that while we’re certainly bad, we’re not the worst out there.

The PC identified several primary causes of the decline:

Complex, slow approvals processes.

Lack of innovation compared to other sectors, in part because of the ‘chilling

effect’ of frequent regulatory changes.

Lack of scale, with the average residential building construction firm employing fewer than 2 people.

Workforce issues, with inconsistent licensing and regulations between jurisdictions contributing to low labour mobility and difficulties in attracting and retaining skilled workers.

Some of those are interrelated. For example, as Glaeser et al found, restrictive zoning and slow approvals can lead to a lack of scale, which can then contribute to the lack of innovation in the sector. And so on.

Getting the balance right (or wrong)

Today’s construction workers aren’t lazier or less skilled than their forefathers. If anything, we have more skills and better capital (machines and tools) at our disposal than ever before.

No, the reason construction productivity has stagnated rests squarely on decades of government policy. As the PC put it:

“Policymakers must balance the benefits of regulation – including neighbourhood amenity, reducing carbon emissions, building accessibility, build quality and safety, liveability and environmental protection – against the decrease in construction productivity and housing affordability that such regulations cause. Currently, policymakers do not get this balance right, and one of the consequences is poor construction productivity and less affordable housing.”

I’m sure most of the regulations were passed with good intentions. The problem is that they compound, with each new rule – which can differ not just between states but even between local government areas – creating a cumulative effect that can distort markets, reduce efficiency, and stifle innovation.

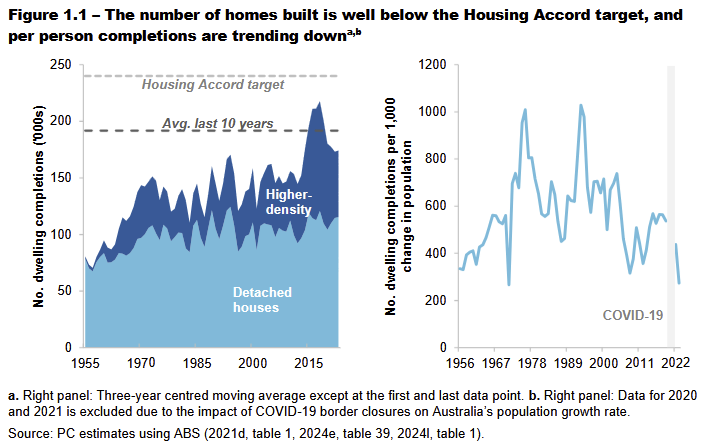

And business as usual just isn’t acceptable any more. The Albanese government’s Housing Accord, in part because it only pays lip service to the drivers of poor construction productivity and expensive housing, is already on track to fail just several months after it began (not that the opposition’s plan is any better).

The key to housing affordability is relatively simple, at least on paper: more supply. But that won’t happen without serious reforms to boost construction productivity.

The difficulty is getting past the political resistance, which runs all the way from the small, vocal minority who really hate density – the ones who run for local council and show up to public meetings – all the way to sitting ministers, who too often “decide it’s more important to focus on their differences rather than finding common ground”.

But if there were a government – state or federal – that was serious about housing, there’s certainly no shortage of solutions.

What state governments can do

Take a big knife and cut up your “burdensome” land-use zoning laws and building regulations, and while you’re at it, neuter your local governments.

Seriously though, here’s what the PC had to say about the damage that inconsistent, ever-changing rules and discretion is doing to the sector:

“Lack of coordination and consistency between decision-making bodies – including at the local government level – can increase the risk and uncertainty associated with housing development. It can also reduce the capacity of firms to benefit from economies of scale and scope. Differences in planning rules, including rules around external design and building materials, can limit the capacity of builders to standardise designs and processes, and so stymie the flow-on benefits of building expertise and ‘know how’ to deliver those designs efficiently.

The burden can also flow through to innovation and appetite for innovation. In some cases, regulation may directly stymie more innovative approaches, for example adoption of prefabrication. More commonly though, the uncertainty created by regulation – especially if it is frequently changing – can make innovation less attractive. Some developers explained how the constant ‘shifting of the goal posts’ could make any innovative approaches quickly redundant.

And finally, the ‘compliance culture’ created by complex regulation seems to have led to a focus on ’ticking the boxes’ to ensure compliance rather than delivering better consumer outcomes.”

One consequence of these inconsistencies is they make dense housing (e.g. apartments) very difficult to build. Yet dense housing was the only type of housing that has seen productivity increase, and for a brief happy period between 2007 and 2014, was even growing faster than overall productivity.

On top of ripping up zoning laws, the PC suggests further state-level reforms to “occupational licensing regimes”, which have been “ramping up… leading to considerable inefficiencies in the provision of skills and reduced productivity in the sector”.

That change alone would “boost GDP by between $5.2 billion and $10.3 billion”.

What the federal government can do

Reform the National Construction Code (NCC) and give it some teeth:

“The NCC – whilst a positive development that remains sound in principle – has grown to more than 2,000 pages. Some aspects of the code and the way it is implemented impose unnecessarily high costs on building construction. Indeed, some updates to the NCC have been implemented notwithstanding regulatory assessments estimating that they impose net costs on society.”

While the NCC was “designed to support consistency”, it has become just another cog in the machine that holds back construction productivity. States and territories even differ in how they apply it, and local government “regulations can also overlap with the remit of the NCC, leading to builders having to alter specifications and designs between local government areas”.

So, the federal government should initiate a complete and independent review of the NCC’s “governance arrangements and membership”, so that it’s forced to abide by its original objectives. It should also include prefabrication guidelines in the NCC, the absence of which “creates uncertainty about the acceptability of prefabricated construction”.

Moreover, although the PC didn’t go this far, my suggestion would then be to withhold various forms of funding (e.g. infrastructure) until each jurisdiction agrees to implement the post-review NCC, and to repeal all local regulations that overlap or interfere with it.

Optimal housing policy

There’s so much that our state and federal governments could do to make housing more affordable, and taking steps to improve construction productivity would be a good start.

I mean, most of the solutions just involve ripping or rewriting many of the rules and regulations passed by previous politicians. Rather than blaming greedy developers or John Howard, look at zoning laws, land release rules, development approval processes, planning requirements, permits, design regulations, standards on materials and fittings, occupational licensing, energy efficiency and accessibility requirements, occupancy permits, and the tax system (especially stamp duty).

Remember, the goal isn’t necessarily to reduce house prices. It’s to make house prices more like those in Japan, a country where the central government has national control over zoning and building rules and prices have barely budged in real terms over the past 24 years.

Basically, housing policy should aim for house prices that grow more slowly than wages so that we, as a country, can afford to buy more housing as we get more productive and wealthier, not less!

Comments

Comments have been disabled and we're not sure if we'll ever turn them back on. If you have something you would like to contribute, please send Justin an email or hit up social media!