Can Xi Jinping rescue China's economy?

The question in the title of this essay starts with “can”, but it could just as easily be “will”. That’s because while it is of course possible that Xi Jinping could rescue China’s economy, everything he has said and written in his lifetime makes me think he’s not capable of actually doing it. Sure, he might be able to tweak a policy here or there, improving the economy from its current trajectory. But the decisions needed to properly right this ship are simply beyond him: Xi made his bed a long time ago, choosing to move China back towards the policies of Mao Zedong instead of Deng Xiaoping; he’s not going to change.

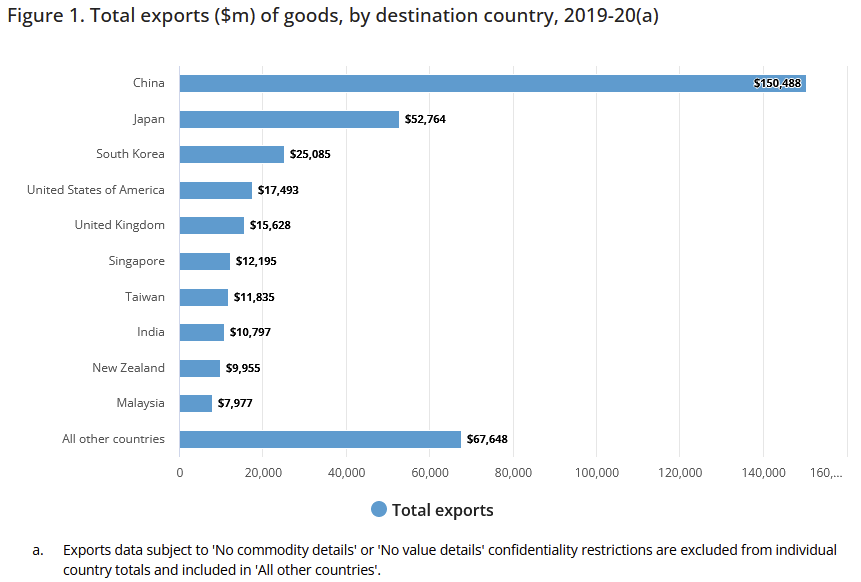

Now, obviously a slowing China has big implications for Australia. It is by far our largest trading partner, responsible for nearly 30% of our exports and over 20% of our imports. Most of our exports to China are commodities, especially iron ore, which in 2019-20 accounted for 56% of our goods exports to China. It really does swamp all other countries in terms of its importance to Australia.

If China’s economy slows, it affects us. A lot. But perhaps just as important as China’s growth itself is the composition of that growth. For example, if Xi Jinping looks to transition away from the long relied upon ‘growth’ plan of real estate bubbles and infrastructure projects of dubious merit, then China many not need as many of our commodities during the next cycle.

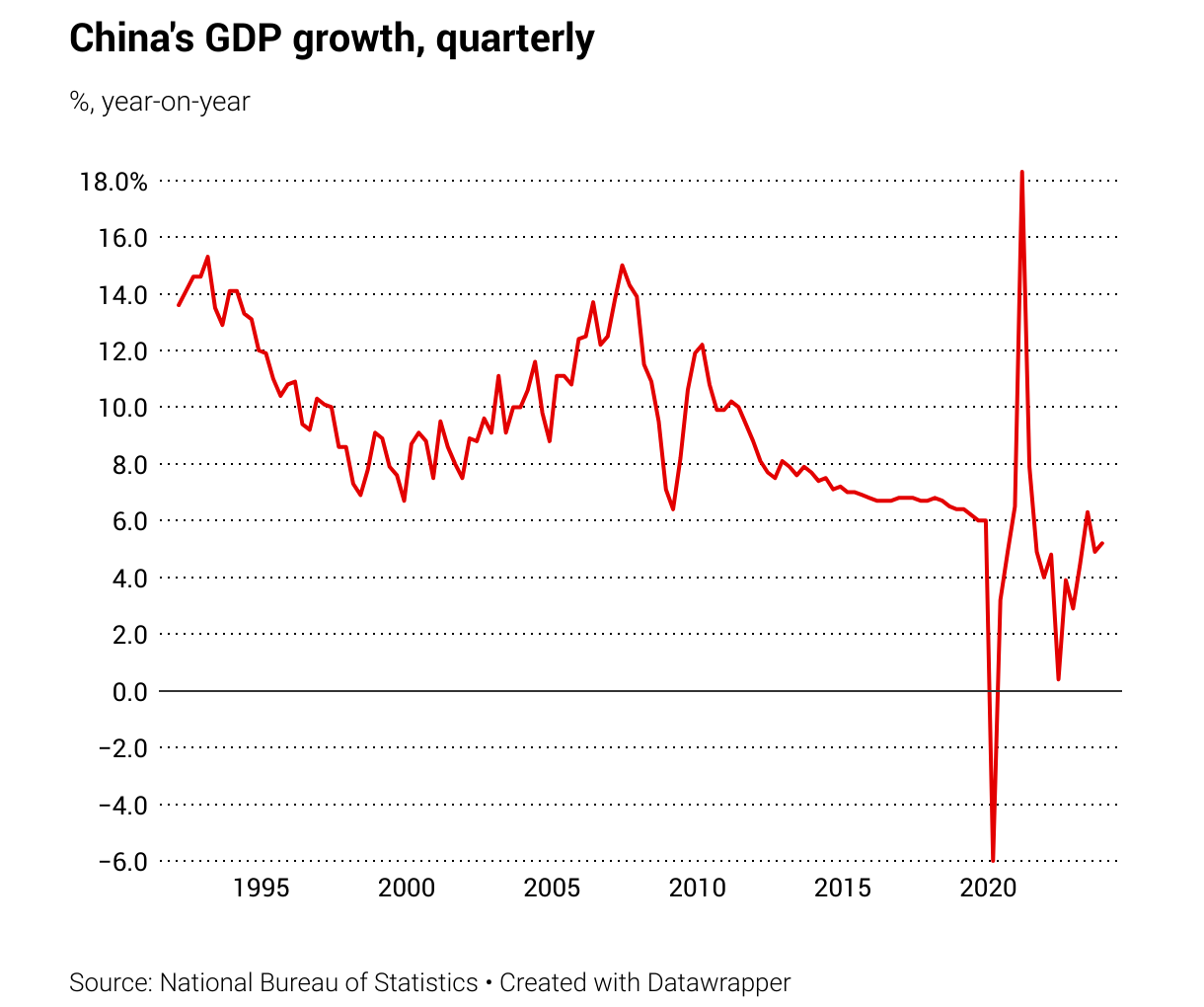

Just a quick look at the broadest indicator of economic growth, gross domestic product (GDP), and it’s clear that China has been slowing for years. It’s now at serious risk of falling into something resembling the middle income trap, i.e. never truly getting rich before it gets old. It might be the world’s second largest economy but its GDP per capita is still below half that of Japan’s, and not much more than a third of Australia’s.

Sure, Xi might claim he’s not overly concerned about China’s slowing growth – his mantra of " common prosperity", which has mostly served as justification to cut down successful businesses in tech, property, and tutoring, suggests as much – but that doesn’t mean he can sit idly by as China falls into stagnation. Economic growth is still as, or more important, in China than it is in Western economies; they still publish annual growth targets, after all.

Crushing entrepreneurship won’t help

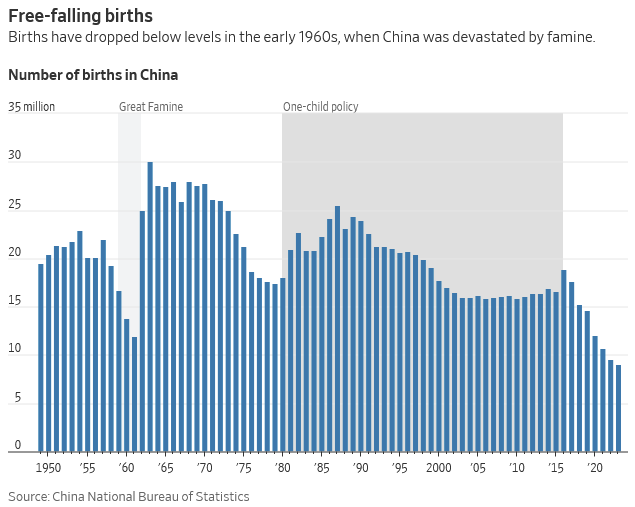

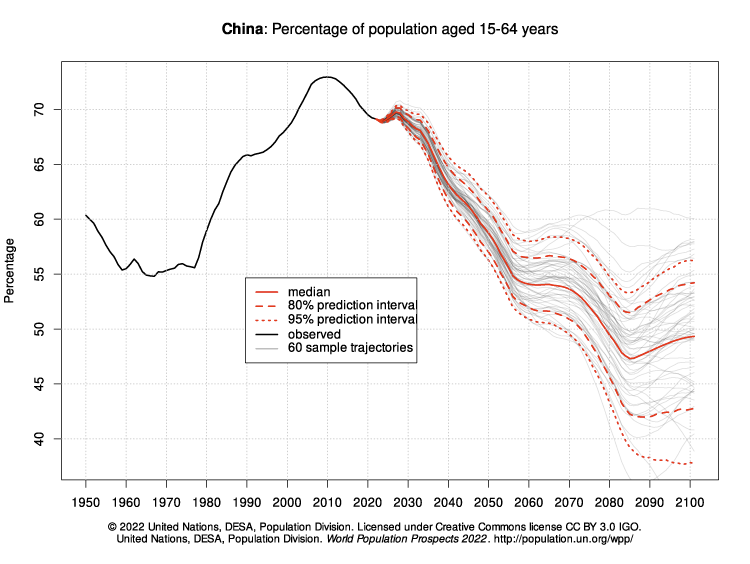

There are a few forces working against Xi. For one, China’s positive demographic dividend has ended due to rapidly declining birthrates.

That will contribute to its demographic situation only worsening from here, with its working aged population ratio reaching something resembling today’s Japan by around 2050.

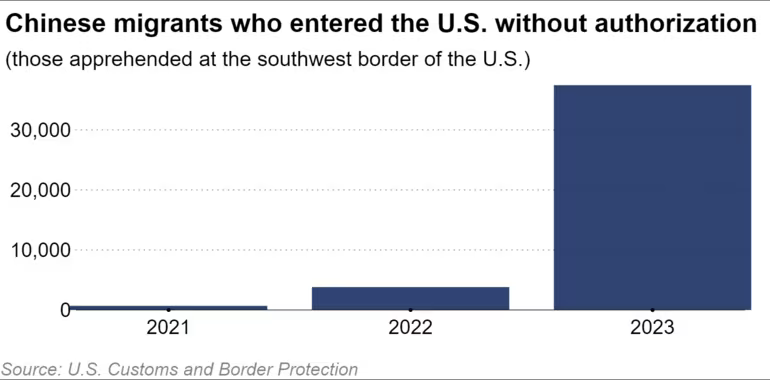

Unlike countries such as Australia, Canada and the US that also have low birth rates, China also has a lack of inward migration: not only do people not want to move to Xi’s China, but tens of thousands of Chinese are now paying considerable sums to be smuggled into the US via the Mexican border, despite being located across the Pacific Ocean.

You may have seen this now-infamous tweet, which suggests that it’s not the poorest Chinese attempting such a move but the relatively well-to-do.

I’m sure many of the poorest Chinese would try to do the same, if they had the means. In a colourful interview between US ambassador to Japan, Rahm Emanuel, and ChinaTalk’s Jordan Schneider, Emanuel summed up the exodus of talent from Xi’s China as follows:

“[T]he biggest thing that he [Xi] does isn’t crushing the private sector or favouring the state control, etc. China has quite an entrepreneurial culture, and he crushed their entrepreneurship — and in crushing their entrepreneurship and the tactics he adopted, he crushed the confidence of the world in China.

As you and I are sitting here talking, he’s holding a conference with business leaders — mainly US, but others from around the world — hoping to encourage them to come back. It’s very hard to have people come back and invest when you’re arresting them. In 2010, years ago, you used to get people in companies to raise their hand and say, “Okay, I want to move to Beijing or Shanghai or wherever, and move with their offices.” But now, you can’t get anybody in Japan, Europe, or the United States to raise their hand and say, “I’d like to move my family to a city where I could get arrested any given day and be in lockdown.” So they have now lost the confidence of the world.”

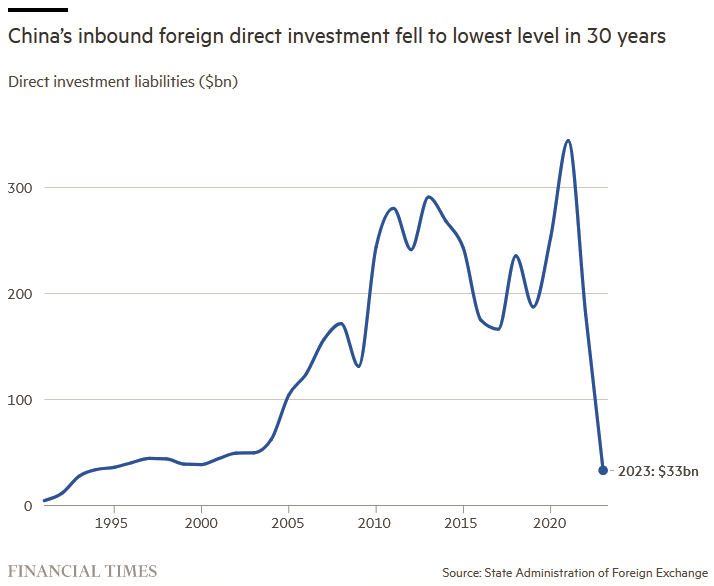

Xi Jinping now has his not-so wolfish mouthpieces travelling the world, trying to drum up new foreign investment. But Xi’s China is no longer a place for entrepreneurs, and foreigners – scorned by executive arrests, the government’s overbearing Covid response, or even what happened to investments in China-ally Russia after it invaded Ukraine – aren’t taking the bait.

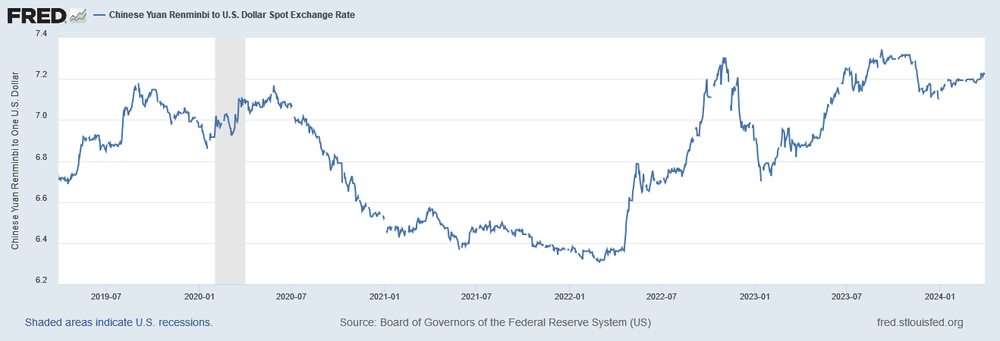

Ever wonder why so many Australian capital city auctions, especially in the upper end of the market, have so many Chinese bidders? Capital is always trying to flee China, and the yuan is close to as weak as it has been since it was allowed to adjust slightly to market forces after the Great Recession.

China is not at risk of a currency crisis – it still has ample foreign currency reserves which it continues to accumulate as part of its huge export operations – but if it wants to transition away from relying on exports by increasing domestic demand and self-reliance without opening its capital account, then it could have a problem in the future.

And that’s exactly what Xi Jinping claims he wants to do through his own version of industrial policy, which is all about finding so-called “new quality productive forces”.

“New quality productive forces”

The FT recently published a good discussion of Xi’s industrial policy, the slogan of which is “rooted in 19th-century Marxist thinking”.

“In recounting Xi Jinping’s foresight as an economic planner, the Xinhua essay pointed as far back as Mao’s cultural revolution. In the 1970s, a teenage Xi led the development of biogas-generating facilities in a rural village, replacing burning wood for lighting and cooking — an early example, it said, of leveraging “new quality productive forces”. Among such forces today, according to Premier Li, are the “new trio” of electric vehicles, lithium-ion batteries and solar photovoltaic cells. Exports of these items rose 30 per cent to $147bn last year, according to official customs data.

…

While experts are mindful of the opacity surrounding Beijing’s plans — no national-level targets have been set for future-orientated industries — there is little doubt that an important change is under way. They also point out that it aligns with Xi’s overarching aims of technological self-reliance and resource independence for China.”

To be clear, Xi’s plan is not new; it’s also known as import substitution. It is not the road to prosperity, but it is a way to reduce one’s dependence on foreign countries, which understandably appeals to Xi given his ongoing tensions with the US and the prospect of another Trump term in 2025.

But it can come at great cost. Argentina, once one of the wealthiest nations in the world, fell into that trap after Juan Perón assumed power in 1946, a man who " saw industrialisation as a mean of achieving the goals of his nationalistic and populist policy of increasing the real consumption, employment and economic security of the masses of workers":

“Import substitution gave the Peronist state control over resource allocation in the economy. By deciding which industries to protect and where to channel national credit, the Peronist government was able to discipline industrialists and determine the destination of investment.

…

The triumph of the industrialisation model under a closed economy, over time, and even after the demise of Perón, led to the adoption of a scheme of industrial integration which consisted of completing every step of the production process, from capital goods and inputs to final goods, inside the country’s borders, in evident contradiction with the post-war tendency of developed countries.”

As a result, Argentina became a “developing” economy within a couple of generations.

Same old, same old

To be fair to Xi, he doesn’t appear to be going that deep into import substitution. He actually looks to be trying to replicate the old China model of coal, steel and other dirty manufacturing in newer ‘green’ alternatives, such as solar, wind and electric vehicles. If so, China will still be dependent on the rest of the world for exports and the commodities it needs as inputs into those industries. Here’s the FT again:

“Cheung at Soas argues that Beijing’s plans need to be viewed in the context of Xi’s focus on supporting industries that first help national security and second can be harnessed “to make China great”. She says the plan makes sense in terms of Xi’s ideology and his aims for regime stability and national security. But failure would risk making China a less consequential global economy.”

China won’t get developed economy rich, or become “great”, using the same model of being the world’s lowest-cost producer of green products, just as it didn’t get rich by being the lowest-cost producer of almost everything else. Instead, it risks perpetuating the same structural weaknesses that have hindered its economic transition, such as an over reliance on exports, excess capacity and a lack of domestic demand, and sluggish market-driven innovation.

But becoming rich is not Xi’s goal; his overriding purpose is to maintain power and avoid an economic crisis, where the people rise up against him. Xi, remember, doesn’t have the best track record as a policy innovator. In fact, it’s not clear that he’s good at anything other than rising through the political apparatus in China and having his competition ‘disappeared’. You can cause a lot of economic harm and still avoid an uprising (look at the Kim’s in North Korea).

In fact, just look at Xi himself: since coming to power, just about every economic policy he has initiated has failed. First it was the Belt and Road Initiative, which has seen around $1 trillion in funding provided for transportation, energy and infrastructure projects in more than 70 countries. According to Wharton management professor Minyuan Zhao:

“China is hoping that by coordinating all these projects – by connecting all the railways, connecting the waterways with the railways — every single project will generate more return in the aggregate.”

Over ten years later, and the Initiative has not produced the fruit that Xi had hoped. Rather than economic returns, he has run into delays, cancellations, debt-servicing and corruption concerns:

“A dozen poor countries are facing economic instability and even collapse under the weight of hundreds of billions of dollars in foreign loans, much of them from the world’s biggest and most unforgiving government lender, China.”

China will almost certainly have to write off billions of dollars’ worth of losses on these projects, and its reputation in some of these counties has been irreparably damaged.

Then there was Xi’s pandemic response, which saw the entire country locked down for years, with Xi pledging to live Covid-zero forever… at least until that plan started killing people in other ways, such as by trapping them in burning buildings, leading to widespread protests that forced a rapid pivot.

Another of Xi’s ‘captain’s calls’ was Made in China 2025. Announced in 2015, it was Xi’s first venture into industrial policy but was quietly abandoned in 2018 as the US trade dispute really took off. This is the one Xi policy that ‘went away’ but really didn’t: it now forms the basis of his “new quality productive forces”.

Alas, just like all of Xi’s other plans it will also fail, at least in terms of achieving its stated aims of creating “productive” growth. That’s because Xi is the one deciding what the “productive forces” are, yet bears very little personal costs if capital is misallocated. As Sowell eloquently put it in Knowledge and Decisions, “the most fundamental question is not what decision to make but who is to make it—through what processes and under what incentives and constraints, and with what feedback mechanisms to correct the decision if it proves to be wrong”.

Xi has very few constraints, faces the wrong incentives (maintain power at all costs), and doesn’t have the feedback mechanisms – i.e. market discipline – needed to make the right decisions. While I have no doubt that he will create enough “winners” that China will continue to globally dominate various green industries, it will come with costs higher than the benefits, and the Chinese people will be worse off than if he had just left them to discover their own patterns of exchange.

This is Xi’s China

No amount of “new quality productive forces” can revive an economy that is struggling through decades of structural mismanagement, " including corruption, massive debt, local protectionism, and overcapacity".

In 2021, Rogoff and Yang estimated that China’s real estate sector made up around 25% of its entire economy, “and is now running into late Soviet era style decreasing returns problems in this sector”.

But China is still the world’s second largest economy, and not all of its entrepreneurs have been purged by Xi. It will – and already has – produced winners in “new” growth areas, such as electric vehicles (EVs).

Take BYD, which is now a very successful, internationally competitive car manufacturer. China heavily subsidised such companies for a number of years, so this is surely an example of modern industrial policy done well, right?

Not necessarily: China has over 300 domestic car manufacturers, many of which – including, believe it or not, the catastrophic failure of a real estate developer Evergrande – were incentivised to enter the market by large government subsidies. Many will surely fail, with costs perhaps greater than the value created by the winners. And it’s not even clear that BYD even needed government subsidies at all, given that it was initially backed by Warren Buffet, who invested a relatively large 10% equity stake way back in 2008 when it was a “an obscure Chinese battery, mobile phone, and electric car company”.

Buffet and co-investor Charlie Munger liked BYD because of its CEO, Wang Chuanfu, whom they said “is a combination of Thomas Edison and Jack Welch – something like Edison in solving technical problems, and something like Welch in getting done what he needs to do. I have never seen anything like it”.

That was a year before the Chinese government even started subsidising electric vehicles, several years before Xi’s Made in China 2025 or “new quality productive forces” listed it as a state-targeted sector. No doubt Wang Chuanfu was in the right place at the right time, but it’s hard envisioning a world where he didn’t succeed in creating China’s, and potentially the world’s, largest car manufacturer – with or without subsidies.

What Xi Jinping did create were a lot of losers that became dependent on subsidies. More worryingly for China, his attacks on entrepreneurs means the next Wang Chuanfu may have already left, or have been bid into an unproductive enterprise only to have his or her talents wasted. That is Xi’s China, and it won’t change until his time is up.

Don’t fight it

So far, Australia’s politicians have been relatively quiet about China’s “new quality productive forces”. In the US, for example, Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen recently accused China of “clean energy dumping”, or attempting to “flood the world with cheap clean energy exports”. That’s because the US government, through its Inflation Reduction Act, is spending a trillion dollars to produce the same goods China already does but at higher cost.

It may not be long before Australia’s politicians start to respond in the same way. One reason solar is significantly more expensive in the US than Australia today is because of Obama and Trump’s tariffs on cheaper Chinese solar panels to “buy time for the domestic solar manufacturing industry to mature”. Now that we’re also subsidising domestic solar manufacturing in Australia, you can be sure that future politicians will stand up for any “local jobs” that are threatened by Chinese imports, regardless of the cost it imposes on everyone – not to mention its own climate goals.

But the thing is, no one can stop Xi from forcing his taxpayers to subsidise domestic exporters for our benefit. If we want to succeed in world where China no longer wants as many of our commodities, we’re going to need a flexible economy that embraces these gifts from Chinese taxpayers, freeing up production, consumption and investment capacity in other sectors in the Australian economy.

Just as we eventually embraced cheap Japanese cars, we should welcome cheap Chinese cars, solar panels, windmills and whatever else their government is willing to pay us to take. By all means, we should voice any concerns to bodies such as the WTO, as industrial policy via subsidy can set in motion a dangerous political race to the bottom as countries seek to defend their own domestic industries. But for Australia, attempting to out-subsidy China would be futile. Instead, we should embrace the consumer surplus they’re offering, ensure our economy is flexible enough to adapt, and sell them goods and services in which we have a comparative advantage in exchange.

Comments

Comments have been disabled and we're not sure if we'll ever turn them back on. If you have something you would like to contribute, please send Justin an email or hit up social media!