China's deflationary spiral

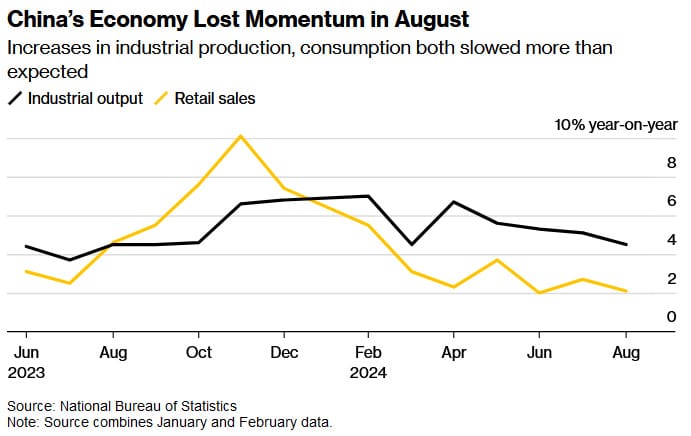

The economic situation in China just keeps getting worse. To the extent that they can be trusted, a series of recent data releases confirmed that the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) 5% growth target is going to be very hard to achieve this year:

“Data published Saturday showed industrial output marking its longest slowing streak since 2021 last month, while consumption and investment weakened more than expected.”

Here’s the accompanying chart:

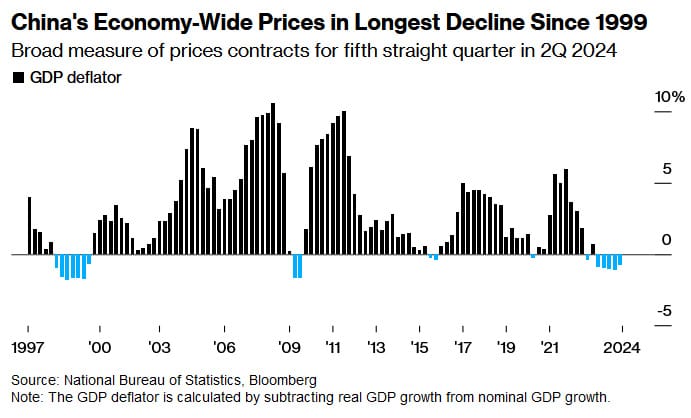

Those rates of growth wouldn’t be bad at all in an advanced economy. But China still hopes to grow at developing economy rates, which is hard to do when sectors like manufacturing are slowing and outright deflation has taken over in many other areas: China’s GDP deflator, which measures all prices in the economy (the consumer price index is a selective basket of goods), has shown declines for six out of the last seven quarters:

President Xi Jinping’s response so far has been to order analysts not to discuss it:

“Economists, brokerage analysts, and researchers all told the publication that regulators, their employers, or local media had warned them not to talk about deflation, slumping foreign investment, and faltering growth.”

That, and to tell his officials “to strive to achieve the country’s annual economic and social development goals”.

I’m sure it will work and China will hit, or come very close to hitting, its 5% growth target this year. Not because Xi’s good-vibes-only intervention will revive the ailing Chinese economy, but because the statistical agency is at his behest – and it’s not like China doesn’t have a long history of fudging its numbers for political ends.

But beneath the aggregates there’s a lot going on. And to be fair to Xi, there’s only so much that he can do without losing face or further riling up major trading partners such as the US.

The long shadow

Pundits have been calling for a “bazooka stimulus” to fix China’s economic woes.

The problem with that is most of China’s problems today come from too much past stimulus. Namely, its massive response to the Great Recession in 2009/10 and more recent foray into industrial policy.

At the time, many Western institutions – and the Australian Prime Minister – praised China for its massive rescue package, which lifted global GDP and lit a fire under commodity prices (especially iron ore!). But the means used to achieve it were always problematic:

“In 2009 and 2010, China undertook a 4 trillion Yuan fiscal stimulus, roughly equivalent to 12 percent of annual GDP. The ‘fiscal’ stimulus was largely financed by off-balance sheet companies (local financing vehicles) that borrowed and spent on behalf of local governments… [W]e provide suggestive evidence that local governments used their new access to financial resources to facilitate access to capital to favoured private firms, which potentially worsens the overall efficiency of capital allocation. The long run effect of off-balance sheet spending by local governments may be a permanent decline in the growth rate of aggregate productivity and GDP.”

China’s stimulus crowded out the private sector because it was predominately allocated to favoured firms (e.g. real estate developers) and low-productivity, state-controlled companies. In the short-run that boosted economic activity, but because it was almost certainly a less productive use of those scarce resources than the next best options, it came at the cost of future growth.

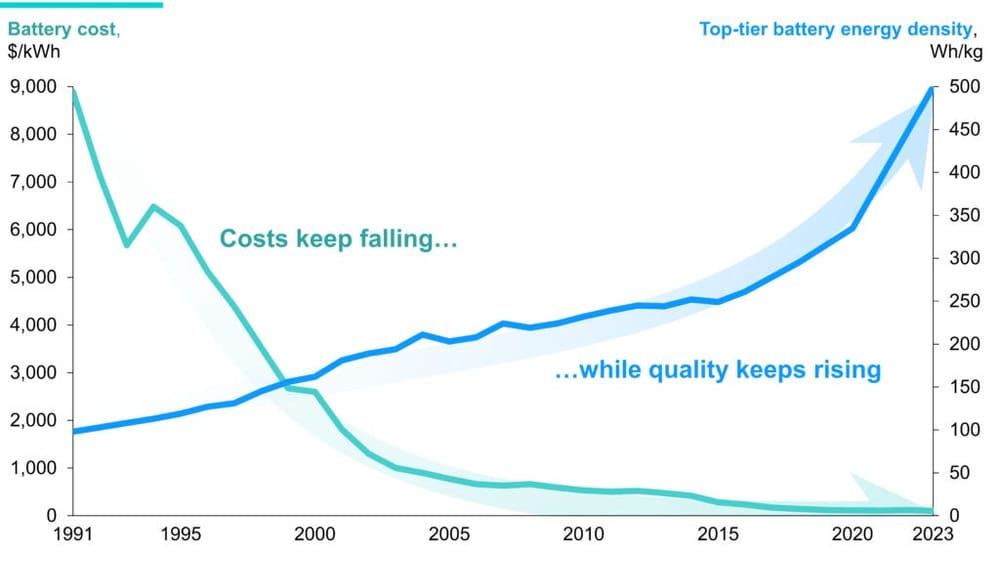

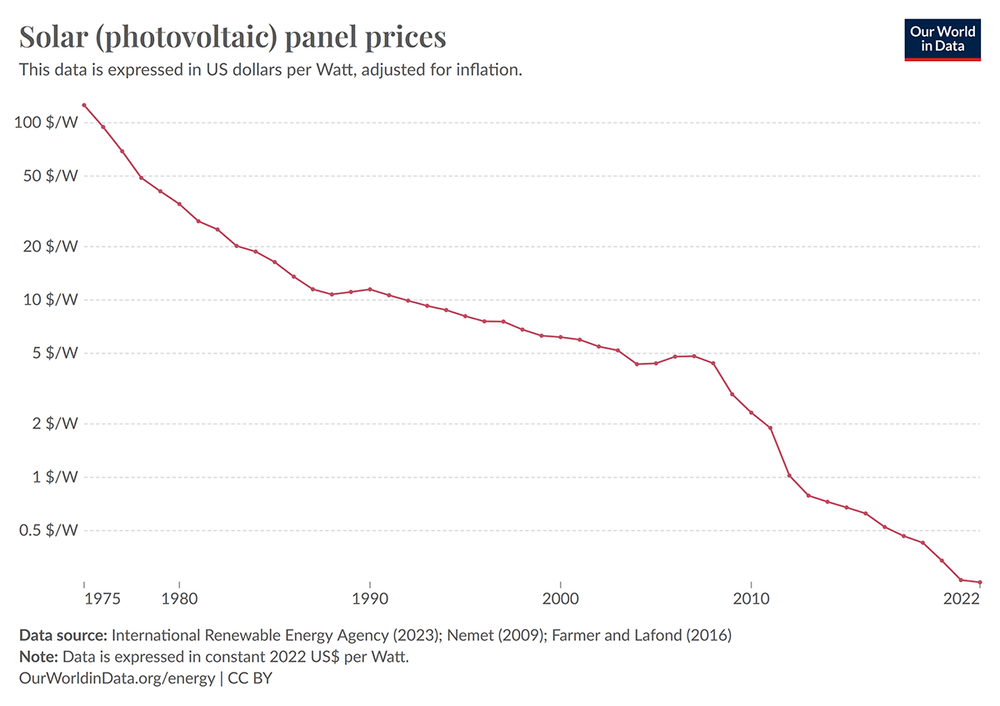

Xi Jinping then came to power in 2013 and not only further concentrated economic activity in less productive state-controlled firms, but also forcibly redirected private capital to sectors he believes are “new productive forces” with industrial policy (e.g. subsidies, rebates, credit allocation), such as solar panels, electric vehicles and batteries.

China is now a world-leader in all those sectors, but there appears to be significant over-investment. Chinese consumers can only afford a fraction of what’s being produced, and even the global economy is struggling to absorb it all, with prices plunging in all three sectors.

China’s manufacturers – many of which were encouraged to invest in these areas because of generous subsidies – are struggling for profitability, and many “will not survive the fiercely-competitive environment”.

So, it’s no wonder then that Europe and the US, amongst others, are pushing back on what they call Chinese " dumping": for political reasons (concentrated benefits, dispersed costs), they would rather produce these goods locally and effectively tax their consumers and other parts of their economy instead of accepting China’s taxpayer-subsidised gifts.

Doing the impossible

But all of that puts Chinese policy-makers in a bit of a bind. In macroeconomics there’s something called the trilemma, which describes the impossibility to have a fixed exchange rate, an open capital account, and an independent monetary policy all at the same time:

“The point is that you can’t have it all: A country must pick two out of three. It can fix its exchange rate without emasculating its central bank, but only by maintaining controls on capital flows (like China today); it can leave capital movement free but retain monetary autonomy, but only by letting the exchange rate fluctuate (like Britain – or Canada); or it can choose to leave capital free and stabilise the currency, but only by abandoning any ability to adjust interest rates to fight inflation or recession (like Argentina today [pre-2002], or for that matter most of Europe).”

Here in Australia, we chose monetary autonomy, a floating exchange rate and an open capital account, while China chose to “manage” capital flows, the exchange rate and monetary policy. It’s basically trying to have its cake and eat it too; to do the impossible.

That’s perhaps why China’s monetary policy is excessively tight at the moment, with nominal GDP growing at just 4% (it’s always a warning sign when nominal GDP grows by less than real GDP!). Broad money (M2) growth peaked in February 2023 and has been slowing ever since, while narrow money (M1) actually started contracting in April. Given where retail sales are at, it’s likely that money velocity has fallen, too.

Basically, China desperately needs to ease monetary policy. But doing so would cause one of two things: a depreciation in the exchange rate, which would probably force a retaliation from the US and other countries with potentially even larger impacts on the domestic economy than the monetary easing itself; or capital flight, which would raise the risk that the current malaise becomes a full-blown financial crisis.

Neither of those are likely to be particularly appealing to Xi Jinping, which is why he has so far taken the vibe approach – he can’t actually ease monetary policy as much as he needs to without breaking something else. But given that he also hasn’t changed any of his destructive economic policies, the longer this goes on, the worse the eventual bust will be.

Entrepreneurs not welcome

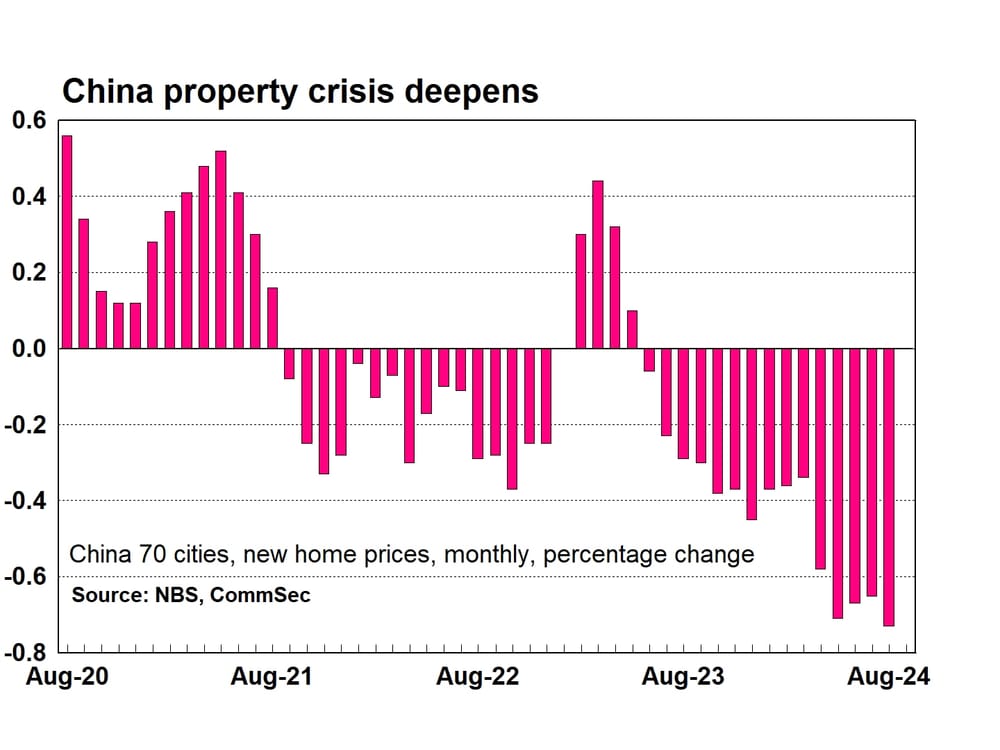

Perhaps the only positive thing Xi is doing is starving the real estate sector of credit, rather than re-inflating that bubble for the umpteenth time. In August, China’s new home prices fell for the fifteenth straight month at the fastest pace since 2014:

But he’s also suffocating the rest of the economy by keeping monetary policy too tight, ensuring that China’s savings are being misallocated with industrial policy, and discouraging the more productive private sector under the guise of “common prosperity”.

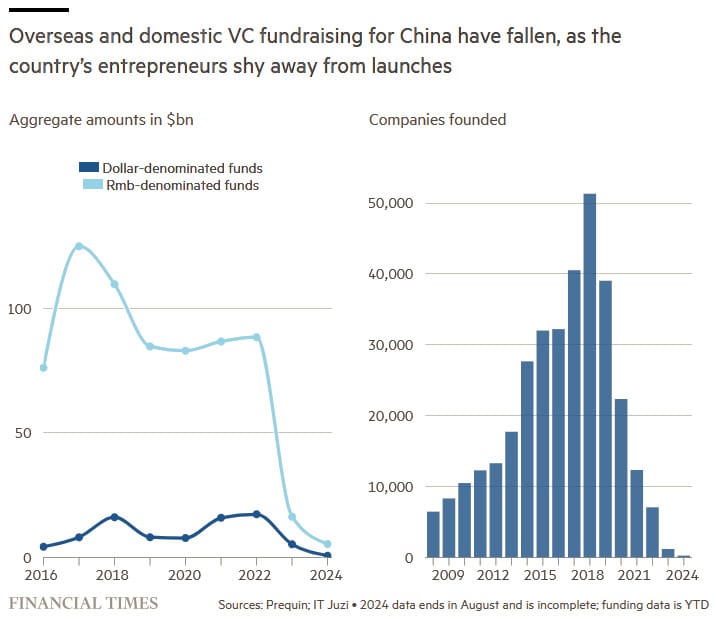

As a result, the venture capital scene – which is how most ultra-productive tech start-ups are initially funded – has evaporated due to slowing growth and the:

“…political decisions taken by President Xi Jinping that have dramatically changed the environment for private business in China — including a crackdown on technology companies regarded as monopolistic or not attuned to Communist party values, and an anti-corruption crusade that continues to ripple through the business community”.

The Chinese government under Xi is increasingly ‘managing’ economic activity out of Beijing, with the result being misallocated, unproductive uses of resources. We all know about China’s ghost cities and bridges to nowhere. But it’s also misallocating investment in things like data centres:

“In April 2022, Chen Gen, a guest lecturer at Peking University, argued that the government-led buildout of high-efficiency data centres ahead of demand would artificially decrease prices and lower profits, thereby hurting tech companies.

Another Chinese researcher, Wang Yuanzhuo, argued in a March 2022 piece that the initiative should focus on demand-driven applications:

‘From past experience, the high social interest and economic benefits of national-level projects easily produces “bandwagoning” and “blind construction and investment,” as seen in new energy vehicles and chip manufacturing, resulting in unfinished projects and even harm to local economic development.’

These fears are not unfounded. When rolling out new computing initiatives in 2021, one of the government’s stated goals was to increase the utilisation of western data centres from 30 percent to more than 50 percent — which indicates a lack of commercial demand for the data centres already built in the west. Adding additional capacity without making those data centres more commercially desirable is unlikely to accomplish much.”

Build it and they will come, right? Add to that Xi Jinping’s credibility problem, and it’s no wonder private investment has been declining since 2018:

“China’s leaders have tried to regain the trust of entrepreneurs. Policymakers are drafting a private-sector promotion law. But if the party’s mood were to turn hostile again, new laws would offer little protection. China’s ruling party cannot convincingly restrain itself: it lacks the power to limit its own power.”

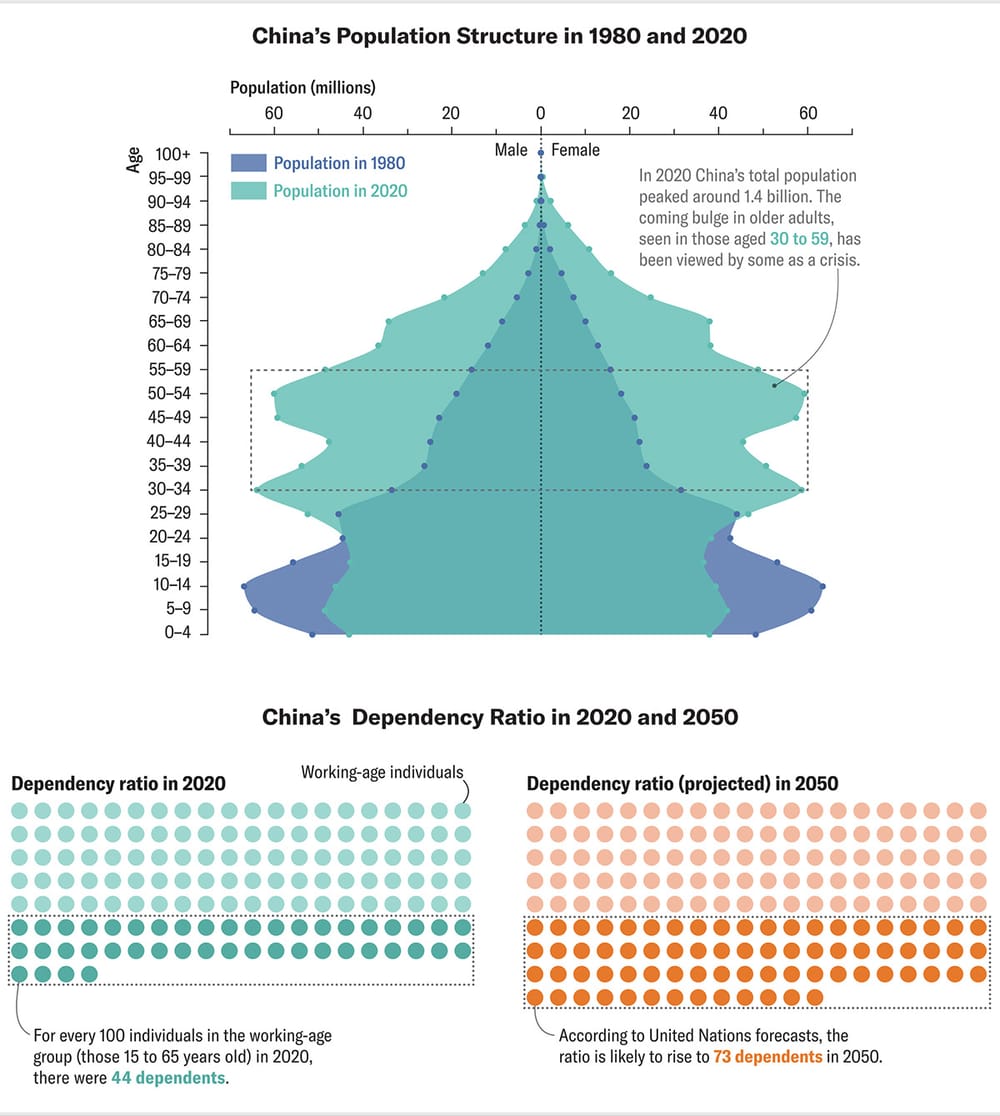

Old before it gets rich

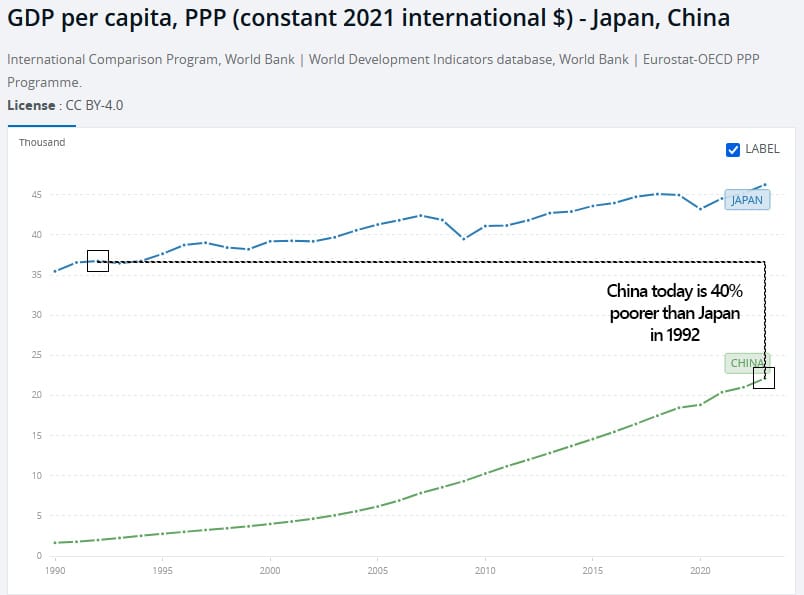

Xi Jinping is in a bit of a predicament. All of the warning signs – worsening demographics, a burst asset bubble, unnecessarily tight monetary policy and deflation – are pointing to a Japanification of its economy.

The problem with that is unlike Japan in 1992 (when its infamous asset bubble burst), China is not yet a rich country, even when adjusting for purchasing power parity (i.e. relative cost of living):

But while it’s still 40% poorer than 1992 Japan, its demographics are similar: 20% of China’s population is now aged over 60, and that’s projected to rise to forty percent by 2050. In 1992, around 18% of Japan’s population were aged over 60 (it’s now over 35%). 1992 was also about when Japan’s working aged (15-65) population peaked; China reached that point in around 2010.

So, it probably won’t surprise you to learn that China’s ultra-long-term bond yields are now below those of Japan’s, the poster child of debt deflation:

China’s 10-year and 30-year bond yields have also hit fresh all-time lows, as the country’s growth slows and its demographic picture continues to deteriorate.

The thing about China is that the CCP won’t get the situation get too bad; the biggest risk to Xi Jinping is if enough people lose their jobs and start protesting. So, when the economy is suffocating the government can’t help but breathe a bit of life into it, even if it comes with even greater costs a few years down the road. It’s why whenever there’s a steel and iron ore winter, a temporary spring is never too far away.

There’s also a potential saving grace for Xi on the horizon: lower rates in the US and most of the West, which will ease China’s monetary policy through the exchange rate channel. But such relief will only be temporary; there are no easy fixes for China here. It can remain poor with command and control state-directed investment and industrial policy, or undergo painful structural reform and cede economic power to the private sector. Only one option seems likely with Xi Jinping at the helm.

From an Australian perspective, the growth phase is well and truly over; China muddling along and doing just enough to stave off a depression will mean no more iron ore and coal revenue windfalls. Our various governments are actually going to have to make tough spending, tax and reform decisions to pay for the debts they racked up during the China boom.

If this is the recession China had to have, then we’re probably going to be dragged down with it, too.

Comments

Comments have been disabled and we're not sure if we'll ever turn them back on. If you have something you would like to contribute, please send Justin an email or hit up social media!