Closing the gap by making it larger

I’m not sure why, but Prime Minister Albanese seems to have saved some of his worst policy ideas for the tail end of his first—and perhaps last, if polling and prediction markets are to be believed—term in government.

The latest example was revealed on Monday as part of the Prime Minister’s annual Closing the Gap statement to Parliament, during which Albo unveiled… price controls for remote communities:

“We are also tackling issues of access to affordable food in remote communities.

Consumer advocacy organisation Choice found on average groceries cost more than double what they do in capital cities.

And supplies can be erratic. The resulting food insecurity can have serious health impacts, including cardiovascular and kidney disease.

Today I am pleased to announce we will ensure the costs of 30 essential products in more than 76 remote stores are the same as what you’d pay in the city as well as boosting warehouse capacity to shorten freight distances and to make supply chains to remote communities less vulnerable.”

These communities are not easy to access. For example, the Choice report cited by Albo said that just getting to the Tiwi Islands, home to just 1,400 residents, was problematic:

“There are usually two ways to get to the Tiwi Islands: a short flight from Darwin on a small plane or a longer SeaLink ferry ride. When CHOICE visited the community in September the ferry was out of service and had been for weeks. A barge arrives in town twice a week bringing in food supplies and other heavy goods.”

It’s completely reasonable for prices of goods – which, while not specified by Choice, appears to include fresh produce – to be higher in such remote, sparsely-populated locations.

But having correctly identified a problem, Albo’s solution is at best half baked. While his idea to improve warehouse capacity to shorten freight distances will help somewhat, the price caps on “essential products” will almost certainly make the lives of people who live in these remote communities much worse.

Price controls are never the answer

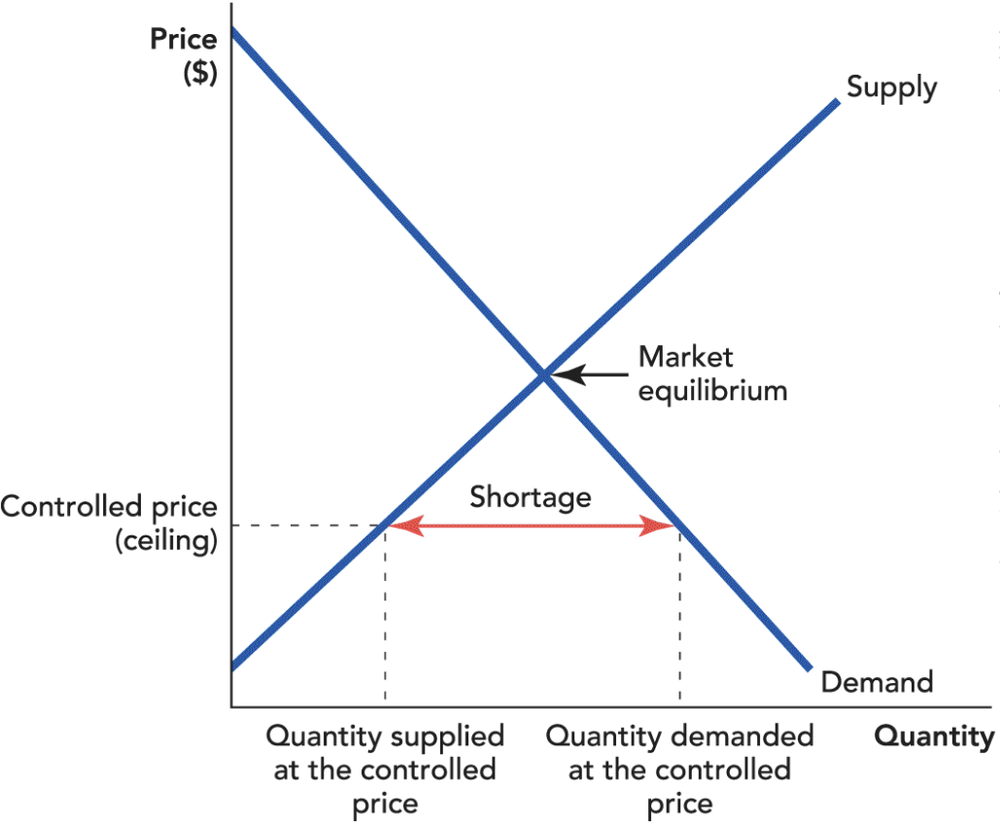

I’m not making a controversial point here; hundreds of years of rigorous research and real world case studies have shown that price controls don’t work in theory or practice. Indeed, just about every introductory economics textbook will have a chart that looks something like the following that shows the effect of a price cap:

Now it’s true that a shortage, as depicted in the chart, doesn’t always emerge. That’s just the most likely outcome; it really depends on how businesses and consumers respond given their specific constraints. Some of the other possible costs, which are not mutually exclusive, include:

- Reductions in quality to compensate for the lower prices. No more brand names or three-ply toilet paper!

- Queuing and other search costs. A shortage of some items may force people to drive elsewhere to find a product, or order it in.

- A general loss of gains from trade ( deadweight loss).

- Resource misallocation, because goods will not be made available where they’re most needed. For example, consumers in remote regions with the highest willingness to pay will now have no way to signal that to suppliers, nor do those suppliers have an incentive to supply them given the price caps.

The only valid economic argument for price controls is where there’s a monopoly, although even that isn’t without consequences – by capping the prices a monopolist can charge, you reduce its profits, eroding some of the incentive it had to increase quality by innovating or cutting costs.

Moreover, a better way to deal with a monopoly supermarket, if one were to exist, would be to remove any restrictions that limited competition and led to the formation of the monopoly in the first place (such as costly infrastructure, which Albo at least acknowledged).

Albo’s economic ignorance will cause real pain

Prices are essential for economies to function; they guide economic activity, and if you stop them from working, you remove a critical signal that can leave the economy direction-less and inefficient. As FA Hayek wrote in what was perhaps his best essay, prices coordinate activity and conserve scarce resources without anyone even knowing why or how:

“All that the users of tin need to know is that some of the tin they used to consume is now more profitably employed elsewhere and that, in consequence, they must economise tin. There is no need for the great majority of them even to know where the more urgent need has arisen, or in favour of what other needs they ought to husband the supply. If only some of them know directly of the new demand, and switch resources over to it, and if the people who are aware of the new gap thus created in turn fill it from still other sources, the effect will rapidly spread throughout the whole economic system and influence not only all the uses of tin but also those of its substitutes and the substitutes of these substitutes, the supply of all the things made of tin, and their substitutes, and so on; and all this without the great majority of those instrumental in bringing about these substitutions knowing anything at all about the original cause of these changes.”

Without the higher prices, there’s less incentive for suppliers to bear the high cost and logistical challenges of trucking goods from their urban warehouses to an unreliable and infrequent ferry, or expensive flight. Goods will instead be sent to their next most profitable locations, leaving residents of remote communities like the Tiwi Islands with even more erratic food supplies.

To the extent that products are still delivered to places like the Tiwi Islands at all, they will be of lower quality—and probably less healthy—such that the goods on offer more accurately reflect the artificially suppressed price. And if Albo thought current prices were bad, just wait until a black market emerges. Want fresh oranges? Well do I have a deal for you – at 10x the metropolitan price!

So, given all these potential but likely negative consequences, why would the Albanese government pursue such a policy? Enter the timeless wisdom of Yes, Prime Minister.

The politician’s syllogism

From Wikipedia:

“The politician’s syllogism, also known as the politician’s logic or the politician’s fallacy, is a logical fallacy of the form:

- We must do something.

- This is something.

- Therefore, we must do this.

The politician’s fallacy was identified in a 1988 episode of the BBC television political sitcom Yes, Prime Minister titled ‘Power to the People’, and has taken added life on the Internet. The syllogism, invented by fictional British civil servants, has been quoted in the real British Parliament.”

Honestly, the politician’s fallacy is the only justification I can think of for this policy. There’s just no way it survived Treasury’s input, which means it was probably dreamt up by a staffer in Albo’s office who was tasked with coming up with some “impactful” policy ideas ahead of his big Closing the Gap speech, read the Choice report, and had an “aha” moment.

We must do something [expensive regional goods], this is something that we can do [price caps], therefore, we must do this.

Check, check, and check!

I only hope that the more sensible heads in the Albanese administration manage to prevent it from ever going live, water it down so much that it’s ineffectual, or Albo loses the election and never gets to implement it.

Honestly, the worst thing about this whole saga is that food insecurity in remote communities is a legitimate issue, and Albo could have addressed it without the unintended consequences his policy will cause.

Here are just a few ideas:

One, provide residents of these communities with vouchers or just straight up cash (which, unlike vouchers, avoids distortions by allowing consumers to decide how to allocate it). Unlike Albo’s price controls, such a subsidy would increase the supply of essential items because they would raise demand, increasing the profitability of supplying them with goods.

Two, incentivise the use of online shopping, perhaps by upgrading the community’s infrastructure (Starlink satellites?). To the extent locals’ knowledge is lacking, invest in classes to teach them how to use a smart phone. This is so obvious that even the Choice report caught it:

“Gerald Kaggwa, who has been living on the island for two years explains how he tries to encourage local residents to buy their groceries online from Woolworths or Coles in Darwin and get it delivered via the barge.

‘We help people to open online accounts and then they do online shopping. They can access shops in Darwin which have cheaper-priced products,” he explains. “If you spend $150 at the shop, you will have roughly a $30 charge for freight on the barge, but then the same goods may cost $400 in the shop here, so it will save a lot of money.’

Despite offering to set up online accounts for his clients, he says there hasn’t been much uptake, something he puts down to the fact that many people don’t have money to plan ahead for next week’s shop. Low levels of internet connectivity and online literacy are other issues.”

Three, target supply itself. Do the infrastructure improvements as planned, but also offer incentives to suppliers – supermarkets, Amazon – to create delivery hubs or pick-up points in remote areas. This could be done through the tax system and would help to offset the higher costs of servicing these regions.

Four, remove any barriers that might be preventing competition such as zoning or licensing requirements. The government could even designate these regions as some kind of ‘special economic zone’, do away with many taxes and red tape, and stand back as entrepreneurs experiment with solutions.

The government could have done one or all of those. My point is there are so many things the Albanese government could have done without messing with prices. In fact, of all the possible solutions out there, the chosen option might be the worst of the lot.

Comments

Comments have been disabled and we're not sure if we'll ever turn them back on. If you have something you would like to contribute, please send Justin an email or hit up social media!