Cyclone Alfred's insurance fallout

Cyclone Alfred has now well and truly dissipated, but the damage it caused will linger for some time—and not just its physical toll. An early estimate from ratings agency S&P put the insured damage at up to $2 billion—which would “match, or exceed, some of Australia’s largest natural catastrophes in the past ten years”—while the economic damage from the loss of activity could be much greater.

But there could also be a policy cost. Not one to waste a crisis, Prime Minister Anthony Albanese (Albo) said that “we will certainly hold the insurance companies to account”:

“This is a time where they need to do a bit of repair of their relationships with the Australian public, by doing the right thing and making payments immediately for people who are eligible… That’s what people expect.”

Well, yes, we should want these companies to fulfil their contractual obligations—that’s a feature of Australia’s rules-based society. I just hope that’s where it ends, and that by saying he wants the government to “hold [them] to account”, Albo isn’t hinting at future intervention in the insurance market, as opposition leader Peter Dutton did.

After all, Albo did say that “Kochie’s right” in response to a statement from pundit David Koch that could be interpreted as calling for government intervention:

“I reckon they [insurance companies] have been ripping Australians off for the last two years and just in the last quarter, September to December, remember the inflation rate is 2 to 3 per cent. Insurance premiums went up 4 per cent.

Now, all of the excuses were, we had to cope with natural disasters. Yeah, this is the first one for a while. We haven’t had a really damaging storm or cyclone for a long time. Surprise, surprise, because they are all listed companies, their annual profits were through the roof.

…

They have got plenty of money to cover it at the moment I think and they have been storing it up and they have been one of the biggest drivers of inflation over the last two years I think unnecessarily.”

That’s so much misinformation in just a few paragraphs that I’m going to need to break my response up into a few parts: are insurers ripping us off; possible unintended consequences of any intervention; and have insurers really “driven” inflation?

Are insurers ripping us off

Insurance companies frequently find themselves as the whipping boys of Australian discourse. That makes sense; a lot of the population is economically illiterate, politicians love to prey on that and/or are economically illiterate themselves, and insurance—as a dreaded ‘middle man’—is as close to a sitting duck as you can get.

It’s also a sector dominated by a few big players, the two largest of which are QBE and IAG. In their most recent financial reports, QBE and IAG both recorded handsome profits, with insurance margins of 12.0% (from 9.6%) and 15.6% (from 9.7%), respectively. They put that down to a “reduction in natural perils costs [IAG]” and “reduced exposure to perils in North America and Australia [QBE]”.

So, good luck, reflecting the volatile nature of their business.

In the insurance market, margins vary by the type of insurance. For example, margins for life and health insurance are typically much lower (~3-5%), while figures above 15% are not unusual for property and casualty (P&C) insurers such as QBE and IAG. The difference reflects the shorter duration of P&C, the more tangible risks (e.g. car, home), constant risk repricing, and the ability to use reinsurance to manage exposure to catastrophic events (“perils”).

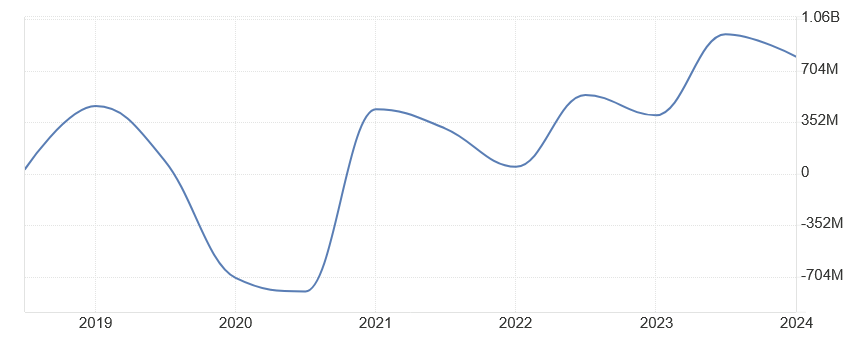

Of course, perils aren’t always avoidable or predictable, and while the big P&C insurers have been quite profitable in recent years, that hasn’t always been the case and may not be in the future—their margins reflect the higher volatility and uncertainty of their risks compared to alternative investments. A quick look at QBE’s net income history shows that it varies considerably by year:

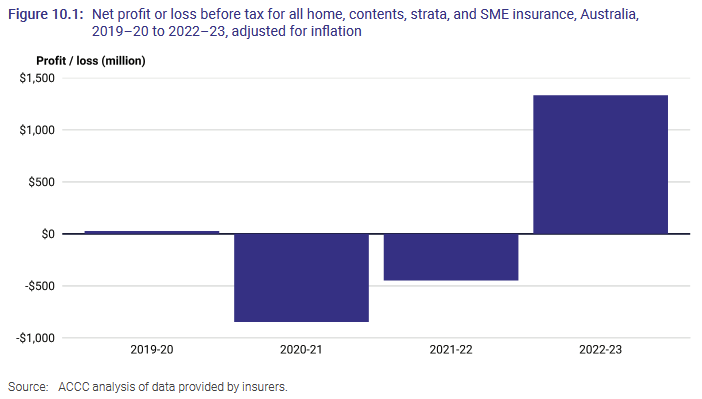

According to ACCC data, “the amount of profit is very volatile”, and the industry can go years in the red because of “the cyclical nature of insurance”:

So no, insurance companies aren’t ripping us off. They’re just making hay while the sun shines, because for all they know another Cyclone Alfred or Black Saturday could be on the horizon.

The unintended consequences of insurance intervention

I’m not suggesting Albo is going to intervene if he deems insurance companies to be misbehaving in the aftermath of Cyclone Alfred. But there are consequences to meddling with that which you do not fully understand.

For example, the recent California fires revealed that many people were uninsured because the state government had capped prices:

“The result is that insurance companies, unable to price their products properly, don’t renew existing policies and stop issuing new ones.”

With any luck, Albo will avoid meddling with prices as part of any attempt at ‘holding them to account’.

But the Albanese government has already meddled in other ways. Most notably, it recently created a cyclone insurance pool, with all insurers obligated to join by the end of 2024. The effect of the pool is to create a cross-subsidy, where people in zero- or low-risk areas pay slightly higher premiums, while those in medium- or high-risk zones pay a lower rate.

That’s all well and good if your sole goal is for more people in hazardous areas to have cover—insurance suffers from what’s known as adverse selection, where the people likely to buy the most insurance are those who are most likely to need it, so they bid up insurance prices until those with lower risks drop out, creating an inefficient and socially undesirable outcome.

In this case, those in high-risk zones want a lot of cyclone insurance, those in no-risk zones don’t want any, and so left alone the insurance companies will be forced to charge those who want coverage extremely high premiums—perhaps so high that no one buys cyclone insurance at all.

By ‘pooling’ all houses and risks together, those in high-risk zones will be more likely to be able to afford insurance, and the higher premiums for everyone else—the government chipped in $10 billion to help ensure this part of the plan holds—won’t rise by enough to deter low-risk people from buying it.

However, in alleviating some of the adverse selection problem, the Albanese government also worsened the existing moral hazard problem. Now that insurance in cyclone-prone areas is artificially cheaper, people are more likely to move there because they no longer have to bear the full cost of that decision—they’re effectively being subsidised to live in high-risk areas.

They’re also less likely to manage their natural disaster risks in the first place because of the insurance subsidy. According to the Productivity Commission (PC):

“High insurance premiums send a signal to the policyholder that they face significant risks and should consider mitigation measures or relocating to a less risky location. Policy measures that break the alignment between natural disaster risks and insurance premiums would obscure some of that information. This could lead to people under-investing in private measures to reduce disaster risks or undertaking building and renovation works that expose more of their property to disaster risks.”

Add that to the time inconsistency problem that governments face when they don’t credibly commit to a pre-determined disaster response, and you get a socially undesirable amount of people living in disaster zones, committing a socially undesirable amount of effort to mitigating their risks.

There’s no good answer here, only trade-offs, and so the government should choose the least bad among a set of imperfect alternatives. But if the government has got the balance wrong—which they appear to have done, at least according to the PC—then we should expect insurance premiums to continue to rise unless the government pours ever-more money into the pool, reflecting the additional risk created by having a larger share of insurance holders locating themselves in high-risk areas.

Have insurers “driven” inflation

Insurance companies are forced to raise premiums in response to inflation on the market value of the insured items, plus all of their other concerns—e.g. current and expected future claims costs and reinsurance expenses.

Basically, when the cost to repair or replace the things they insure—cars, houses, etc—go up in price, premiums must follow by at least an equal or greater amount. It’s why QBE’s annual report includes statements like this:

“Australia Pacific improved its combined operating ratio over the year, highlighting encouraging resilience in light of challenges associated with persistent inflation and exposure to the civil unrest in New Caledonia. The benefit from recent premium rate increases has driven some recovery from inflation challenges in the prior year.”

Notice the tense—this year’s premium increase drove a recovery from inflation in the prior year. Or if you’d prefer an independent source, here’s Fitch Ratings:

“Persistently high inflation and slowing economic growth raise the potential for an unfavourable shift in loss reserve adequacy, led by commercial auto and other liability product lines. The accuracy of insurers’ loss projections for claims severity tied to inflation and litigation risks in commercial auto and other liability business are key determinants of profitability, given the risk of underpricing long tail lines of business with adverse reserve development that drive increases to casualty reserves.”

The last situation a P&C insurer with long tails (i.e. rare but catastrophic events) wants to be in is one where they’ve underestimated inflation and under-priced the risks of rare events by keeping premiums too low, leaving them to wear potentially significant underwriting losses.

In an inflationary environment, replacement costs for insured assets and “social inflation” (legal costs and court awards) can rise quickly and in a non-uniform manner. Insurance companies also tend to hold a lot of their cash in fixed-income (e.g. government bonds), which fall in value when the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) raises rates to combat inflation.

It’s a bit of a double-blow, and forces P&C companies to raise premiums to account for the significant risk and uncertainty caused by inflation, on top of their usual risk-based price adjustments.

So no, contra Kochie, insurance companies haven’t been “one of the biggest drivers of inflation over the last two years”; even suggesting as much indicates a lack of knowledge of both the insurance sector and inflation, which is “an ongoing fall in the overall purchasing power of the monetary unit” (without a change in the value of money, if people were suddenly spending more on insurance, they would have less to spend elsewhere, and hence it would have no long-run impact on overall prices).

All up, it concerns me that those who appear to have a relatively limited understanding of basic economic concepts (Kochie is not alone here) wield such influence over our leading politicians, potentially jeopardising sound policy making in Australia.

Comments

Comments have been disabled and we're not sure if we'll ever turn them back on. If you have something you would like to contribute, please send Justin an email or hit up social media!