Deregulation is an urban myth

Victoria University of Wellington’s Policy Quarterly had an interesting article in its May 2025 issue looking at the size of the state in New Zealand from 1900 to 2028. I was particularly amused by the opening quote that inspired the research, written by… ChatGPT:

“The neoliberal reforms in New Zealand resulted in a shrinking of the state, marked by privatization, deregulation, cuts to public services, and a reorientation of the government’s role in the economy. – ChatGPT, 18 December 2024, in response to the prompt, ‘how did the neoliberal reforms in New Zealand affect the size of the state?’”

ChatGPT’s response is certainly the most commonly-held view. Given how quickly AI is moving, I decided to ask the identical prompt, and received a similar response:

“The reforms shrank the state in both a fiscal sense (lower spending, smaller government workforce) and a functional sense (less direct involvement in production, reduced welfare role). The guiding ethos was to make the state leaner, more efficient, and more focused on enabling markets rather than intervening in them.”

But as the authors discovered, it’s just not true. While government spending on certain items like defence and market-based production fell (the latter thanks to large-scale privatisations), those were the exceptions. The state didn’t just go away—it kept growing while changing the composition of its spending:

“Public spending has been increasingly dominated by social spending, including health, while spending on some other government services, such as defence, has declined relative to GDP. So, while there has not been a consistent erosion or shrinking of the state overall, there is considerable evidence of compositional shifts in the state’s role over time.”

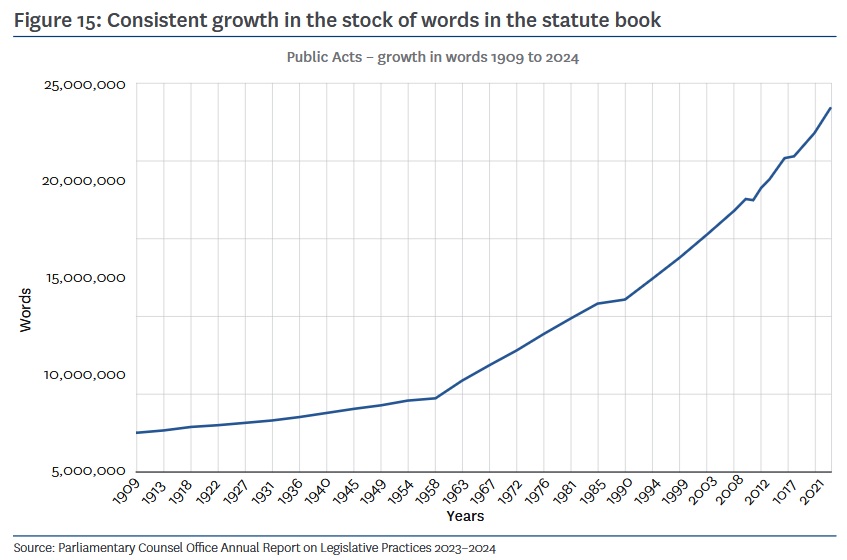

That compositional change was certainly a positive, as government spending on goods and services that can be readily purchased from the private sector is absolutely a productivity killer. But for me, the most jarring insight wasn’t the constant increase in public spending but the ever-growing regulatory burden, as shown in the following chart:

I suspect the data would look similar for Australia. Indeed, according to the authors:

“Regulatory inflation and policy accumulation are general trends not unique to New Zealand. Recent scholarship suggests that globalisation and liberalisation are often accompanied by the expansion of regulatory rules and agents (Vogel, 1996). Interpreting the growth in the size of the statute book is complicated. More words in government regulations may imply more complexity, but does not automatically mean there is increased regulatory intensity or burden of compliance. But the Figure 15 does not lend any support to the notion that any deregulation associated with the regulatory reforms of the mid-1980s and 1990s has led to a reduction in the regulatory state; indeed, the opposite appears to be the case.”

Deregulation is an urban myth!

Comments

Comments have been disabled and we're not sure if we'll ever turn them back on. If you have something you would like to contribute, please send Justin an email or hit up social media!