Does Australia need a DOGE?

It’s no secret that Australia has been in a productivity slump over the past two decades, due at least in part to “creeping inefficiency”. That’s a big deal because, in the long run, productivity is almost everything.

So what can the government do about it? One possibility, as strongly alluded to by opposition leader Peter Dutton—who has already appointed Jacinta Price as “spokeswoman for government efficiency”—is to create our own version of US President Trump’s DOGE.

Much aDOGE about nothing

If you haven’t heard of DOGE by now, it stands for the ‘Department of Government Efficiency’ that Trump set up to be run informally by Elon Musk. Armed with a crackpot team of kids, Musk has been scouring government tax and payment data looking for waste to cut, from US Aid to… cancer treatment trials.

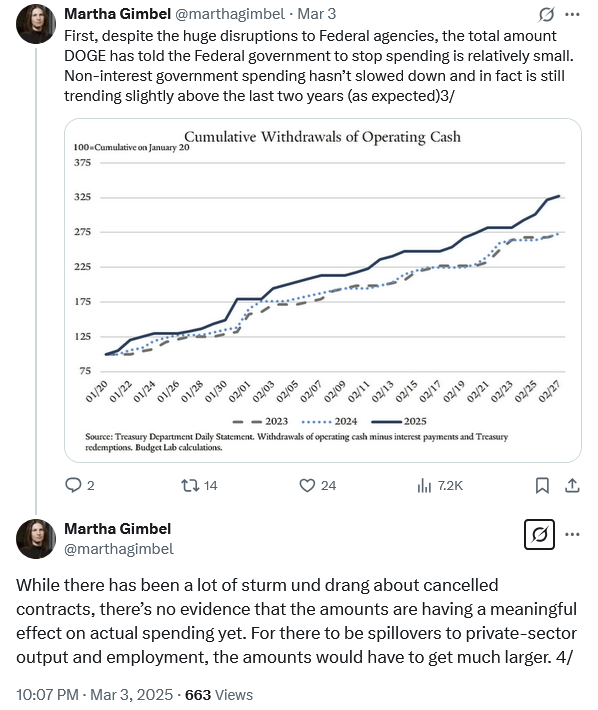

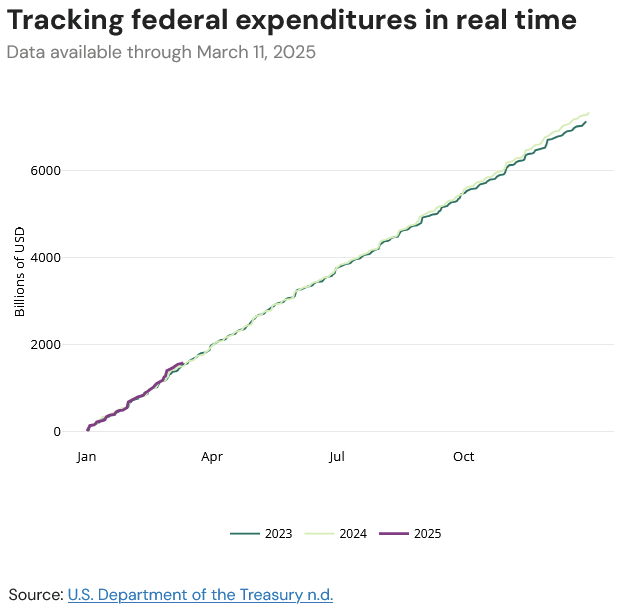

Needless to say, it has been controversial. And while it’s still early days, the signs aren’t all that promising, with the savings so far looking more like a rounding error than anything transformational.

Here’s how it looks compared to entire years, rather than year-to-date.

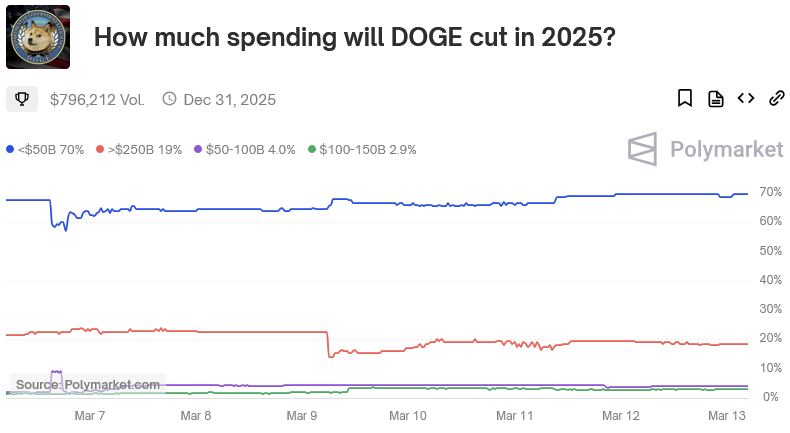

Prediction markets aren’t optimistic of any meaningful cuts, either.

But perhaps that was always the intention. Left of centre pundits have started to suggest that DOGE was set up to enforce “an ideological purge of wokeness”, rather than cut spending. Economist Betsy Stevenson, a former member of President Obama’s Council of Economic Advisers, said DOGE was “performance art… [designed] to dazzle us and have us look away from trillions of dollar in tax cuts to the uber-wealthy”.

From the non-MAGA right of centre, George Mason University’s Veronique de Rugy agreed, while also warning about the disconcerting possibility of longer-term consequences:

“First, for all the talk about cutting government waste and fraud, the DOGE-Trump team seems mostly animated by rooting out leftist culture politics and its practitioners in Washington. It feels that it is less about smaller government than it is about political transformation. While the two intersect, this strategy could fall short.

That’s in part—and this is my second point—because for those of us who care about permanently downsizing government and keeping it bound by constitutional rules to prevent the exercise of arbitrary power, DOGE is mixed. While there is a small probability the approach will succeed in reining in spending or the administrative state, it will be at the heavy cost of reinforcing the power of the executive branch and opening the door to the same abuse when the left is in power.”

Damned if you do, damned if you don’t. Unfortunately—and this also applies to Australia—there’s not all that much a DOGE can do to improve government efficiency, at least not in a way that will show up in the productivity statistics.

Cutting spending is one thing, but improving efficiency requires opening a whole other can of worms.

Most of what the government does, using the framework of Baumol’s Cost Disease, is low-productivity service work like health, education, and law enforcement: a nurse can’t change a bandage any more quickly than she could 30 years ago. While certain parts of those jobs can be made more efficient—say, automating some of the nurse’s data entry tasks with AI—in general, non-routine labour-intensive jobs aren’t likely to experience much in terms of efficiency improvements over time.

But as other parts of the economy such as agriculture, manufacturing, and resources improve their efficiency and productivity, real wages increase and people increasingly want to use their greater wealth to consume even more services—including those provided by the government. Prices and wages in those sectors are then bid up, but because they’ve experienced very little productivity growth themselves, more people are needed to be employed in those sectors and the service sector’s share of the economy grows.

Beware of unintended consequences

There are two ways that a DOGE could tackle that “disease”. The first—which is the option Trump’s DOGE has taken (so far)—is to focus entirely on the supply side, e.g. by slashing jobs at various agencies. That also appears to be Peter Dutton’s focus in Australia, given he has said that he wants to fire 36,000 federal bureaucrats.

However, there’s a reasonable risk that reducing the government’s ability to meet demand for its services will make efficiency worse, not better. For example, there’s evidence that a reason for government inefficiency is the lack of capacity in government departments themselves, along with a lack of competition in the market for government contracts.

Firing a bunch of your best bureaucrats—which is generally what happens with voluntary redundancies or sacking those on probation (e.g. talented individuals who have recently changed roles)—reduces capacity, thereby lowering government efficiency!

Basically, if you don’t first do the hard work of eliminating the reasons for needing so many government workers in the first place (e.g. regulation), the morass only worsens.

Which brings me to the second way to tackle the problem: from the demand side. The only way for a DOGE to meaningfully improve government efficiency would be to address the question of why does the government need so many workers in the first place?

The answer to that is red tape (unnecessary government regulations), green tape (excessive environmental laws), and white tape (compliance obligations that reduce competition). For every application that must be submitted to comply with a rule, a bureaucrat somewhere needs to review it. And a federal DOGE would only be able to do so much; in NSW alone, the environmental planning scheme involves:

- Multiple departments and agencies, each with their own rules and guidelines, including seven separate pieces of legislation totalling almost 1,000 pages.

- 50 related but separate guidelines consisting of over 2,000 pages.

- Over 30 separate government websites or portals from which to draw information on how to navigate and comply with all the different rules and processes.

- The rules are constantly changing—at least ten modifications to the key assessment rules have been made since 2022.

In Western Australia, it took six years to get government approval to run an LNG export plant out of Karratha, and the federal process is still ongoing—all part of a huge tangle that forces bureaucrats and businesses alike into a productivity-killing maze.

If you don’t first untangle the web, fewer bureaucrats simply means fewer reviewers, slowing everything down even more. If the bureaucracy is the O-ring (weak link) that prevents many other activities from being done efficiently, cutting it back without reducing the need for it will only make the situation worse.

A DOGE won’t deliver efficiency

Only after simplifying the rules can you then free up government workers for the private sector. Not only that, but you would also free up many of the private sector compliance officers, in-house lawyers, and lobbyists seeking to carve out exemptions to the rules—plenty of which could be better used doing productive work instead.

But it’s not clear that a DOGE can even scratch the surface of those obstructions. We already have a Productivity Commission that repeats what needs to be done ad nauseam, yet politician after politician simply dither—perhaps because, once in place, special interest groups that benefit will lobby to keep the rules in place.

Perhaps it can help to digitise government services. But even then, the track record isn’t great; because the government doesn’t have the in-house capability—or if it does, it’s swamped by layers of management that make achieving it impossible—it ends up getting outsourced to consultants like Accenture. The inevitable result is a process that can run eight times over budget and deliver very little in terms of efficiency gains:

“As soon as the royal commission got under way, you could see the buzzards start to circle, getting ready to pick off those poor people at DOHAC and extract as much money as possible,” one Canberra IT executive told The Saturday Paper. “What you have to understand about these companies is that their whole modus operandi is to back the biggest truck they can find up to whatever government department or agency engages them, and then fill it with cash as fast as they can.”

Really, what needs to happen is someone has to take a chainsaw to the planning and zoning laws that slow down infrastructure projects and prevent us from making housing affordable. The occupational licensing requirements that restrict labour mobility, raising costs. The all-or-nothing environmental regulations that don’t properly weigh the costs and benefits to society—that ignore the inconvenient truth that trade-offs have to be made. Or the complex tax code that increases compliance costs, and disincentivises work given its over-reliance on taxing income.

It won’t be easy. When the Rudd government commissioned a comprehensive tax review in 2008, it waited months to respond and then only accepted 3 of the 138 recommendations— which were “bastardised beyond recognition”.

The effect of that whole saga (which included the politically-disastrous Minerals Resource Rent Tax) was to scare off all subsequent governments from meaningful tax reform, with the tax system now acting as an even bigger anchor on efficiency and productivity:

“We cannot continue to put increasing reliance on the personal income tax system — not if we want to pursue a productivity-enhancing agenda and also an agenda which enhances workforce participation.”

Look, I’m supportive but not convinced that a federal DOGE in Australia would do anything to improve efficiency or productivity in this country. But it’s not a silver bullet; there’s just no way to give it the requisite authority to tackle the federal- and state-imposed handbrakes on activity. And even if there were, it’s not clear that would be desirable—once in place, such authority could just as easily be used to achieve the opposite ends, should a future government so desire.

So no, Australia doesn’t need a DOGE, because unless it was accompanied by deeper, systemic reforms that address both the supply and demand sides of how our governments operate, it won’t meaningfully improve efficiency.

Comments

Comments have been disabled and we're not sure if we'll ever turn them back on. If you have something you would like to contribute, please send Justin an email or hit up social media!