Does Canada's election have implications for Australia?

The Canadian federal election was held this morning (Australian time). Initially I wasn’t planning to write a note about it, but given the parallels between the two countries and that fact that our very own election is just days away, I couldn’t resist.

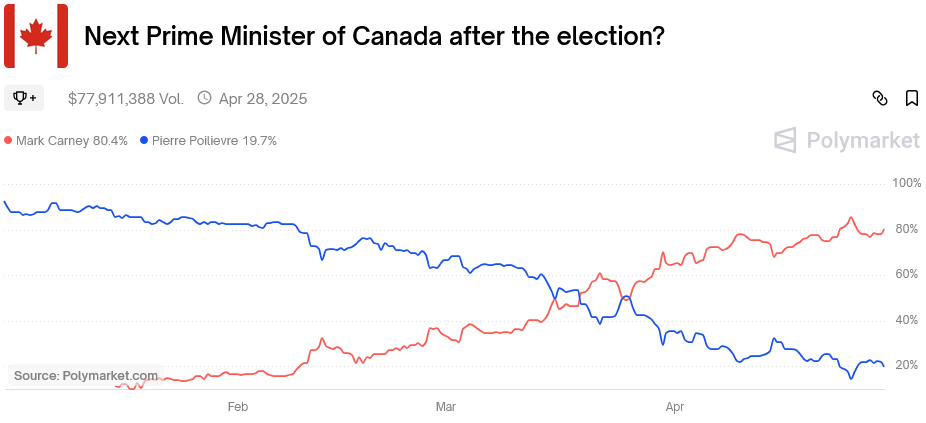

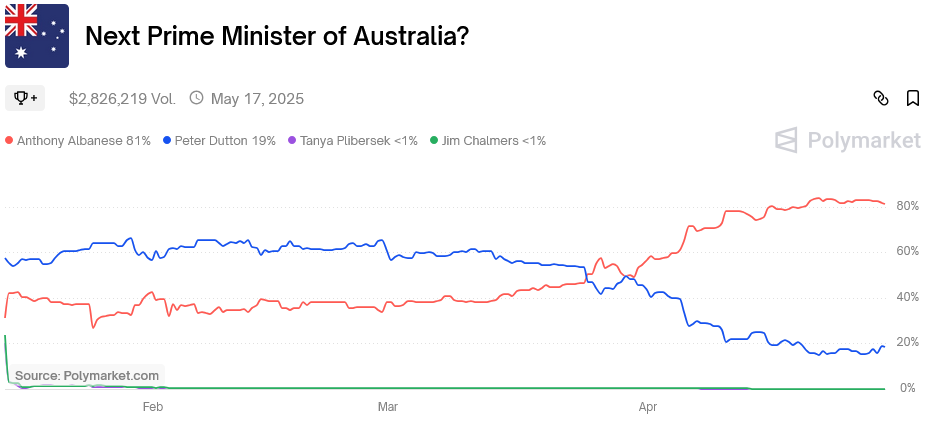

I mean, just take a look at these two charts (note that Mark Carney was much lower than Anthony Albanese early on because he wasn’t yet confirmed as party leader):

Let’s take a look at how it panned out.

The results are in

The incumbent (left of centre) Liberal Party has comfortably secured a fourth consecutive term, with the only remaining question being whether it will be as a majority or minority government.

So, prediction markets were “correct” in the sense that the odds they gave to Mark Carney, which implied that he would win 80 out of every 100 elections, held firm. This was not an election where so-called ‘silent Canadians’ came out in force for the underdog, but a typical election where the favourite won.

The biggest losers so far look to be minor parties like the far-left Greens and National Democratic Party (NDP), and nationalist Bloc Québécois, with a notable swing back to the majors combining with Canada’s first-past-the-post electoral system proving insurmountable.

But that result for the minors won’t necessarily be replicated at Australia’s election, as our preferential voting system is what helps propel people like the Teals into their seats despite their lower primary vote, and Canada’s Senate is appointed on the advice of the Prime Minister, so minor parties like Australia’s Greens have zero chance there.

Change without changing

The major issues in the lead-up to the Canadian election were similar to those in Australia: housing affordability, Donald Trump’s tariffs, bolstering the military, immigration, the addiction and mental health crises on Canada’s streets, and how to best use the country’s vast natural resources.

With the exception of the addiction crisis (phew!), those are broadly similar to the issues that have been debated here. Both party leaders differed in their specific policies, but as in Australia the discussion has mostly been at the margins, with bipartisan agreement on things like cutting immigration, removing roadblocks to development (housing and natural resources), and spending more on the military.

Also like Australia, neither leader was willing to put forward a meaningful plan for boosting the country’s ailing productivity, instead committing to the opposite with a range of big spending, deficit-financed election promises. It wasn’t even until Trump’s tariffs came along that both sides pivoted towards reducing provincial trade barriers; how successful Carney will be in achieving that, given the entrenched rent seekers that will fight it at every step, will be fascinating to watch.

Basically Canadians wanted change, but only of the superficial sort, and Mark Carney—who wasn’t even part of former Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s disastrous government and had never contested a public election until today—did enough by pivoting the incumbent Liberal party to the centre, scrapping things like the unpopular carbon price and vowing to unlock the country’s natural resources that Trudeau had tangled up in red and green tape.

Meanwhile, the Conservative opposition leader Pierre Poilievre had—like Peter Dutton in Australia—unfortunately tethered himself to many of Trump’s policy ideas that were popular… until he started attacking Canada and the rest of the world. Indeed, Trump even reiterated his desire for Canada to become the 51st US state on election day, plunging the proverbial dagger deeper into Poilievre’s heart.

In a sense, Australian voters have been presented with a similar choice—superficial change, with two leaders trying to distance themselves from Trump while actively avoiding any discussion of deeper, longer-run issues, ensuring that for all intents and purposes their policies are virtually indistinguishable from one another.

Given such a choice, the favourite is inevitably going to be the devil you know.

Labor’s last chance

Australia only has three-year terms, and we haven’t bounced a government after its first go since James Scullin in 1932—voters like to give governing parties a chance for their policies to be felt before deciding whether or not to kick them out.

So, is there any reason to think Australia’s election might go in a different direction to the Canadian one—that our election is one of the 20 in 100 in which the favourite loses?

I don’t want to rule anything out, but I’d say that’s highly unlikely at this late stage. That makes makes Canada’s election a bad omen for Peter Dutton and the Liberal Party, while Anthony Albanese and his Labor Party colleagues will no doubt be relishing the result—but they had better make the next three years count, because after two terms in power Australian voters tend to be much less forgiving to the incumbent government.

Comments

Comments have been disabled and we're not sure if we'll ever turn them back on. If you have something you would like to contribute, please send Justin an email or hit up social media!