Don't bet against betting markets

As everyone should now be aware, on Sunday Joe Biden stepped down as the Democratic candidate in November’s US election – on National Ice Cream Day of all days! Crazy as it sounds, 2024 will be the first Presidential election since 1976 to not have a Biden, Bush, or Clinton on the ticket.

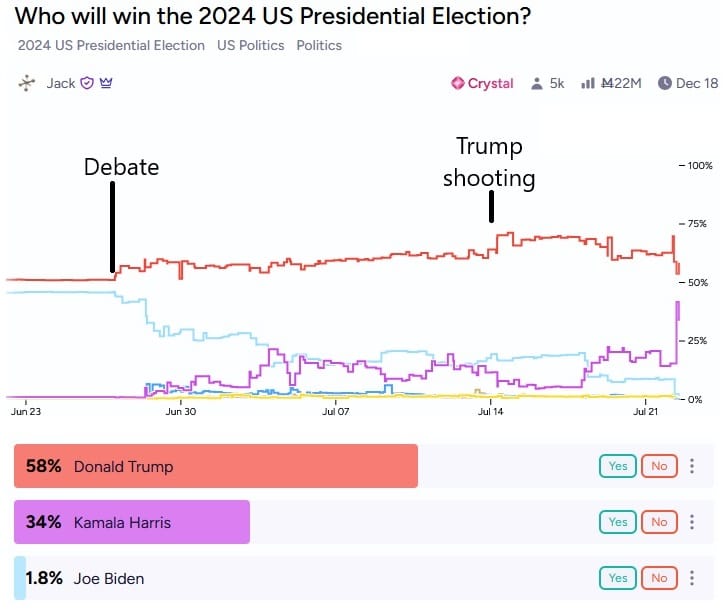

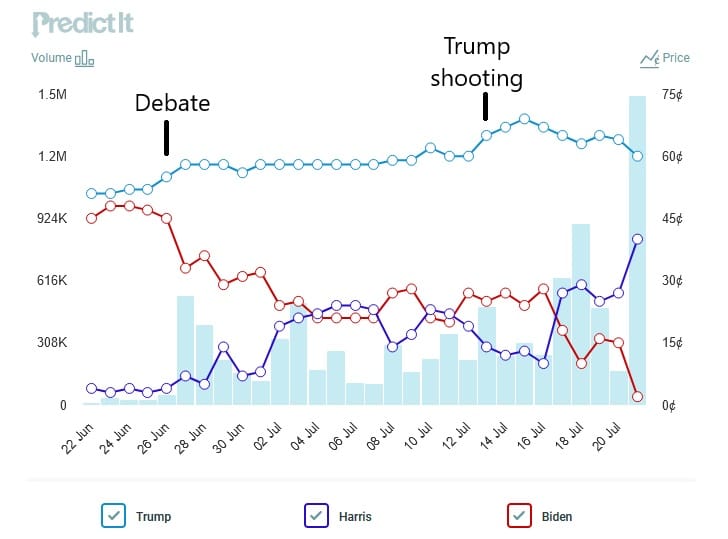

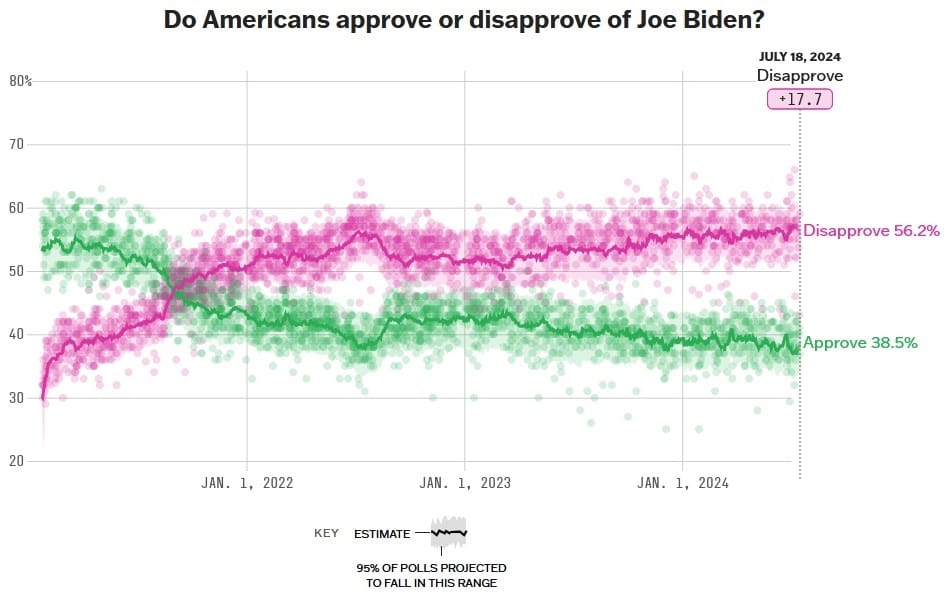

Biden’s demise has been coming for weeks, but it really accelerated following that debate performance in late June. While the assassination attempt on Trump certainly gave the Republican nominee momentum, it didn’t do anything to Biden’s odds – betting markets already had him at just a 25% chance to win by the start of July.

No, Biden’s demise was all about his declining cognitive ability and the fact that most Democrats, let alone all-important swing voters, considered him unfit to serve a second term.

With Biden gone, the focus now moves to the Democrats’ heir apparent: Kamala Harris. Harris was endorsed by Biden in his resignation letter and many of the Democratic apparatchik, including Nancy Pelosi and would-be challengers such as Gavin Newsom, have fallen in line. Curiously, Harris has yet to receive the blessing of the all-important former President Barack Obama and some top donors, so we won’t know for sure until the Democratic National Convention on 19 August.

Still, Harris has in-principle agreement from a majority of delegates and prediction markets have her at ~95% odds to secure the Democratic nomination, which is 10 percentage points above where Biden was prior to his calamitous debate performance. Barring a legitimate challenger putting their hand up between now and late August (and there are almost none left who had yet to endorse Harris), it’s looking like it will be Harris vs Trump in November.

So with the candidates finally settled, what are their respective policies, and what might it all mean for Australia?

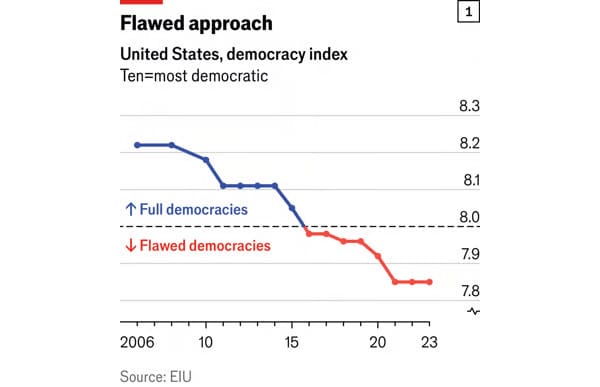

Democracy is safe

I’m going to start with what they have in common. First and foremost, I think the ’threats to Democracy’ of a Trump 2.0 government are vastly overstated. The US might be a flawed democracy, but it still scores strongly on “political participation” and “free and fair elections”.

Where the US falls down is on trust: people mistrust their elected officials, perceive them to be prone to corruption (there’s a Nancy Pelosi stock tracker for goodness sake!), and think that most political figures “don’t care” about “what people like me think”.

A President isn’t going to change those things in four years – many elected officials in the US are basically appointed for life – and even if they could, it’s not clear that Trump 2.0 would do any worse at improving those than a Harris government. Institutions can of course decay, but four years isn’t long enough to undo an established democracy like the US. Indeed, the last three and a half years of Biden/Harris has done nothing to address those problems, either.

To be clear, Trump 2.0 is more than capable of causing considerable economic and political damage, and the risk to democracy is certainly higher than it would be with Harris (not to detract from her ability to also leave the country in a considerably worse state!). But I don’t think that we’re going to be looking at a Xi Jinping-type situation of Trump seeking a third term four years from now; US institutions are strong enough to withstand any such attempts at dictatorship.

Where things get really interesting is in their policies.

While Harris has only been on the campaign trail for a few days, she did run for President in 2020. Harris was also Biden’s VP, so is likely to continue – or even expand – many of his policies into another term.

Two peas in a pod

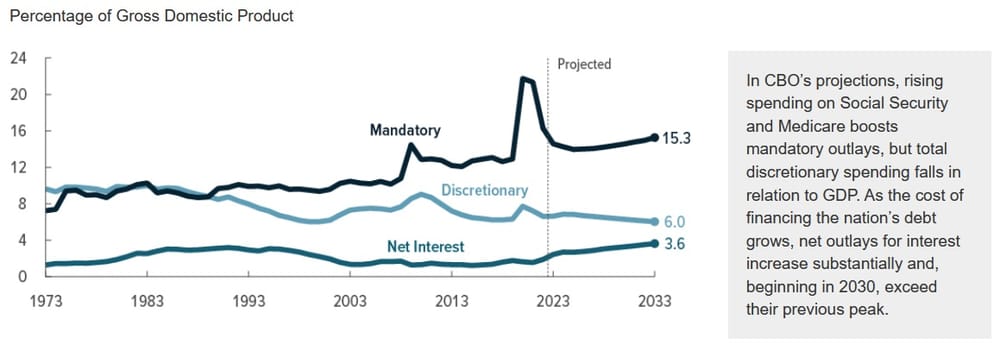

But while they have many differences, it’s also uncanny how similar they are on many issues. For example, neither of them will be able to meaningfully cut migration, as neither candidate plans to do anything about so-called unfunded liabilities such as Medicare and pensions, which are the key drivers of projected US spending and structural deficits.

Immigrants are what are needed to delay that day of reckoning – even illegals – because they’re the ones who, during their time in America, “pay Social Security payroll taxes without ever claiming benefits”:

“The 2024 Social Security trustees’ report contains a sensitivity analysis showing that if future immigration were 35% higher than is now projected, Social Security’s financing shortfall would be reduced by 11%. Immigration can’t eliminate Social Security’s financing shortfall, but it helps.”

Harris will likely continue Biden’s relatively illegal-friendly border policy, while Trump has pledged to deport them all and offset that by issuing green cards to any non-citizen college graduates, of which there are around 1 million every year. Whether Trump is able to achieve either of those promises is of course doubtful, given the immense logistical challenges involved in the former and potential resistance from his advisors and party on the latter.

They are also quite similar on fiscal policy. Both Trump and Harris would likely rack up large deficits while in office, with Trump worsening the situation through tax cuts not offset by reductions in spending, while Harris would continue Biden’s debt-financed, green industrial policy agenda, plus expand social spending even further – in 2020 Harris supported a “Medicare for all” plan, and was one of the original co-sponsors of the ill-conceived Green New Deal.

Perhaps that’s why the Washington Post called this election a battle of progressivism vs progressivism-lite:

“Today, beneath the frothy partisanship, Republican progressivism echoes the Democrats’. Both parties favour significant expansions of government’s control of economic activity and the distribution of wealth. Both promise to leave unchanged the transfer-payment programs (Social Security, Medicare) that are plunging toward insolvency, and driving unsustainable national indebtedness.

And both parties favour tax increases: the Democrats on corporations, consumers and the 3 percent of individuals earning more than $400,000 annually; Republicans on consumers [via tariffs].”

Trump will do things like end the country’s EV mandate and wind back Biden’s emissions standards. He might even restore an executive order from his first term that required removing two existing regulations for every new one, which would certainly help lubricate the gears of economic activity – that, along with expected tax cuts, are one reason why stock markets will almost certainly react more positively to Trump than Harris.

But don’t expect Trump to end Biden’s wasteful industrial policies, such as the Inflation Reduction Act; he’s no opponent of government-directed investment, so will probably simply re-brand and reallocate those subsidies away from things like solar panels and into his favoured sectors, including fossil fuels.

Brace for another trade war

Where Trump and Harris meaningfully differ is in foreign policy. Trump has said he will end the war in Ukraine, which if you speak Trumpism could just as easily mean ending US involvement in the war, rather than the war itself. Or perhaps it will mean forcing European nations to pick up more of the tab, which is basically his Taiwan policy – under Trump, the US is “no different than an insurance company”, and allies should have to pay for that insurance.

As far as Australia is concerned, we shouldn’t have a problem with the AUKUS deal given that we’re literally paying billions to expand shipbuilding capacity in the US (and UK), and the first subs we’re due to get in the early 2030s – so, after a potential second Trump term expires – will probably be second-hand. It’s hard to see Trump considering that a “bad deal”, though he is a madman so you never really know.

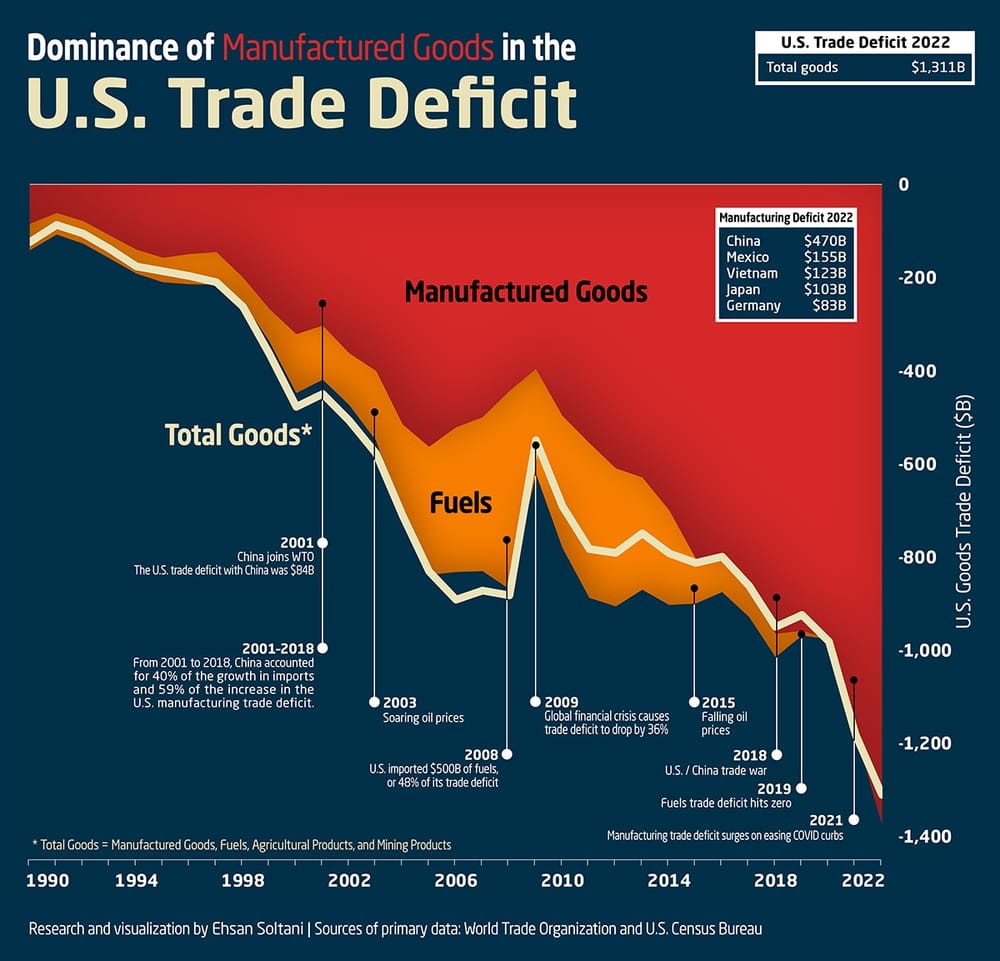

But overshadowing all of that is Trump’s obsession with trade, specifically the accounting identity known as the balance of trade. While Harris will probably maintain the Trump 1.0 and Biden tariffs – she has given zero indication that she’s a closeted free trader and even voted against the US-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) in 2020 – Trump has a deeply-ingrained desire for the US to ‘win’ its trade with other countries, despite economists going back to David Ricardo (1817) dismissing such concepts as nonsensical.

For the US, a large trade (current account) deficit means it also has a large capital account surplus. Basically, domestic demand and the investment opportunities in the US are so strong relative to other countries that it attracts lots of foreign goods and investment, to the benefitof people in the US.

But Trump clearly didn’t pay much attention during his Wharton economics classes. For example, here is Wharton’s Dean Geoffrey Garrett explaining that the trade deficit is no big deal:

“People believe that the trade deficit is like a win-loss record of a soccer team. Exports are good, imports are bad, so if you have more imports than exports, you’re losing. But in the global economy — with global supply chains, global distribution network — that makes, in essence, no sense.”

As international trade Nobel Prize winner Paul Krugman described, exports are actually better viewed as a cost:

“Even more fundamentally, we should be able to teach students that imports, not exports, are the purpose of trade. That is, what a country gains from trade is the ability to import things it wants. Exports are not an objective in and of themselves: the need to export is a burden that a country must bear because its import suppliers are crass enough to demand payment.”

Alas, Trump’s thinking on trade can be traced back to mercantilst times. It’s why charts like this seemingly keep him up at night:

So, expect a Trump 2.0 government to go hard on trade, especially if he reappoints his currently-imprisoned former trade advisor, Peter Navarro, to a senior role in his administration.

That’s perhaps the area where Australia stands to suffer the most, given that we’re one of the most free-trading nations in the world. If Trump kicks off another global trade dispute, as seems likely, it would raise prices and reduce output and employment in both China (almost certainly the main target) and the US.

According to a handful of RBA memos written in 2017-18 and recently released via the Freedom of Information Act, if Trump were to whack China with more tariffs it could “weigh on commodity demand”, reducing exports, consumption and investment in Australia, and therefore GDP and employment.

There’s no reason to think that another trade war wouldn’t hit us in the same way.

Silicon Valley shifts to the right

Another major difference between the two candidates appears to be on tech and big business. While Trump 1.0 was notoriously hostile to Silicon Valley and the big end of town, he has since changed tack: he’s now a fan of TikTok, spoke favourably of Jamie Dimon and even suggested him as a candidate for Treasury Secretary, and is seemingly best buds with Elon Musk, whose ‘X’ platform annoyed him so much the last time around that he created his own Truth Social. His VP choice is JD Vance, a former venture capitalist who looks to be anti-Big Tech but is supportive of a lighter touch for startups, AI and crypto.

So, it’s no surprise that some big hitters in Silicon Valley, such as venture capitalists Marc Andreessen and Ben Horowitz, have publicly backed Trump because of this new-found support for crypto and “emerging industries” such as AI. The Biden/Harris administration has taken a more hands-on approach that Andreessen called an “assault”, and will probably continue to do so under a Harris government.

But the most hated venture capitalist policy is Biden’s proposed tax on unrealised capital gains, which Andreessen called a “destructive tax policy for startups”.

Now, there’s a legitimate argument against the current US tax regime that allows the wealthy to borrow against their stocks until they die, so that they never actually pay any tax – known in tax circles as “buy, borrow, die”. But Andreessen is right that the Biden/Harris tax on unrealised capital gains is perhaps one of the worst ways of doing that.

What would it take for Silicon Valley to come back to the Democrat camp? Matt Stoller speculates that their support for Trump is tactical; an attempt to pull the Democrats back towards the centre, something that’s unlikely to happen with Harris as the nominee given she has historically been to the left of Biden on most issues:

“Andreessen and Horowitz are New Democrats, which is to say they really liked Bill Clinton and Barack Obama. ‘The Obama years proved you could have a pro-business Democratic administration’, said Horowitz, noting the ‘great tech boom of Obama’ and praising the dot com era under Clinton.

…

Biden is threatening this very foundation in two ways. First, he is attacking the basis of technological innovation. Andreessen and Horowitz criticised the Biden administration’s industrial policy for trying to pick which innovations will be important and which won’t, which is wildly inappropriate. No one has ever been able to do that, history is littered with examples of failed arguments about what will matter and what won’t. This need for control, they argue, leads to Biden trying to strangle the blockchain, or crypto, in its crib, with lawless attempts by the SEC to apply securities law to tokens.

…

Andreessen and Horowitz are not partisan Republicans, at all, their goal is as much to change the Democratic Party as get Trump elected. They see Biden as an anomaly, with people in his administration, namely those under the influence of Elizabeth Warren, who ‘flat out hate tech and hate capitalism’.”

But even without support from Silicon Valley’s New Democrats, Harris has had no problem raising funds during the first few days of her campaign. So, it all makes for an exciting, if unusual, final few months of political drama. I find that following US politics is like staring at a train wreck: you know you shouldn’t be doing it, but sometimes you just can’t look away.

So, who will win?

If you want my advice, don’t bet against betting markets or you could end up looking quite foolish, as “Basil” did just a few days ago.

Like Basil, many people thought Biden was a sure thing – why wouldn’t he be, given he had secured all the delegates needed to be the candidate, and had pledged to fight on? But markets weren’t so sure: there was still 21c worth of uncertainty priced in, and ultimately it paid off.

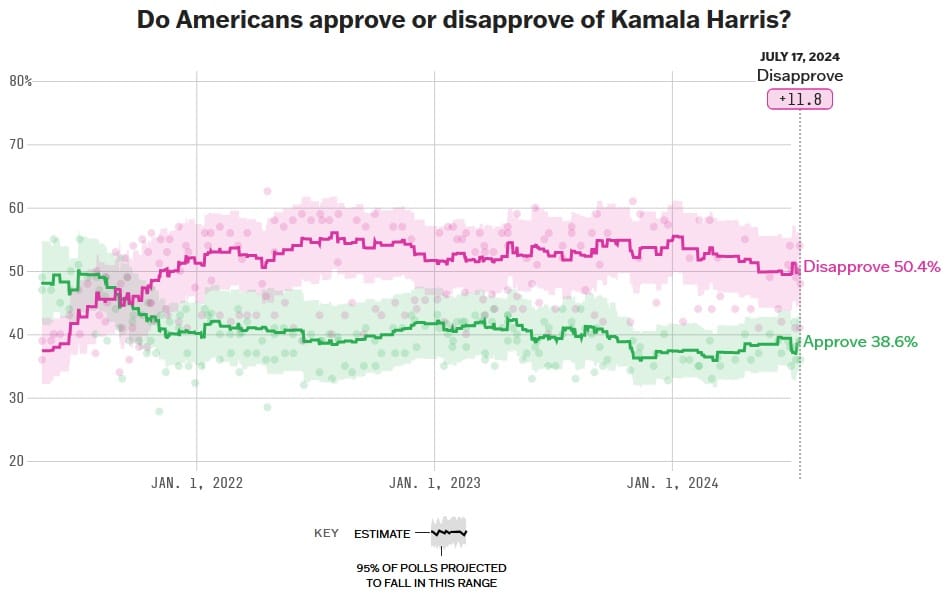

Harris certainly has her work cut out for her: her approval ratings were barely above Biden’s; she either knew that Biden was cognitively impaired and lied about it or – perhaps worse – legitimately didn’t know; she ran a disastrous 2020 Presidential campaign; and her record as VP has been underwhelming.

Betting markets have Harris at about a 45% chance to beat Trump, who sits at around 55%. That gap will narrow even further when Harris officially secures the Democrat nomination, and party power brokers such as Obama publicly endorse her. If Harris can demonstrate that she has moderated her ill-fated, well-left-of-the-median-voter views contributed to a failed 2020 attempt at the Presidency, then she’s a decent shot at winning.

As we saw with Biden, a lot can change in a month, let alone three. Trump is still the odds-on favourite but it’s not the one-horse race that many thought it might be. In 1988 when George HW Bush – also a former VP – won the nomination, he was “trailing Michael Dukakis by substantial margins”, yet managed to turn it into a “near-landslide win” in a very short amount of time.

So, a 55% to 45% advantage for Trump is nothing close to a sure thing. Don’t be like Basil and misunderstand what betting markets are telling us: they are most certainly not selling dollars for 55c, but are rather reflecting the considerable uncertainty that’s in store over the next 100 days.

Comments

Comments have been disabled and we're not sure if we'll ever turn them back on. If you have something you would like to contribute, please send Justin an email or hit up social media!