Don’t blame immigrants for the housing mess

Whether immigrants fuel inflation is a complicated question, in part because there’s no single, uniform “immigrant”. Immigrants can be students, skilled workers, entire families, refugees, retirees, or backpackers. Their ages also vary, as do their consumption, savings, and working patterns.

Each of those features, and how they all come together in aggregate, will affect the role immigration plays on supply, demand and ultimately, prices. At one extreme, an immigrant could be what economists call a low or zero marginal product worker, consuming far more than they produce (e.g., many public services). If the government borrows to finance that consumption, it will be inflationary unless adequately offset elsewhere.

Similarly, an immigrant could be highly skilled, producing far more than they consume. They might even send the surplus overseas as remittances, all of which would be deflationary without an offset.

The degree to which those effects are offset is ultimately determined by the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA), because it controls the money supply, and inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon. For example, when immigrants arrive, many will want to exchange their foreign currency for Australian dollars, and it’s up to the RBA whether it sterilises those exchanges or not. The RBA can either fulfil those exchanges by creating new dollars, or swap them for dollars that already exist. The former may be inflationary, while the latter should be neutral, assuming no changes to the velocity of money.

Given that inflation is a rise in all prices (a decline in the value of money relative to goods and services), the inflationary impact of immigration is a policy decision.

But what about houses?

How immigrants affect relative prices, most notably house and rental prices, is also a complicated question. I’ve written about why before, but it deserves additional treatment now that former Treasurer Peter Costello has weighed in:

“Australia has always been a migrant country, and I’ve always supported immigration, but the levels of immigration now are extremely high. In my day we were at 120,000. That is an enormous adjustment for an economy to bring in 500,000-600,000 people. If they’re in family groups… we’re talking about another 200,000 homes. No wonder we’ve got rental shortages in Australia.

What is holding up GDP in Australia is this enormous immigration. But it’s bringing its own structural problems, pressure on infrastructure and pressure on inflation. What’s going to be driving inflation in the near term? Rents, that’ll be a big driver of inflation. So [immigration is] good, but it’s got to be managed in a careful and considerate way.”

Costello is broadly correct but left out some important context.

Enter the government

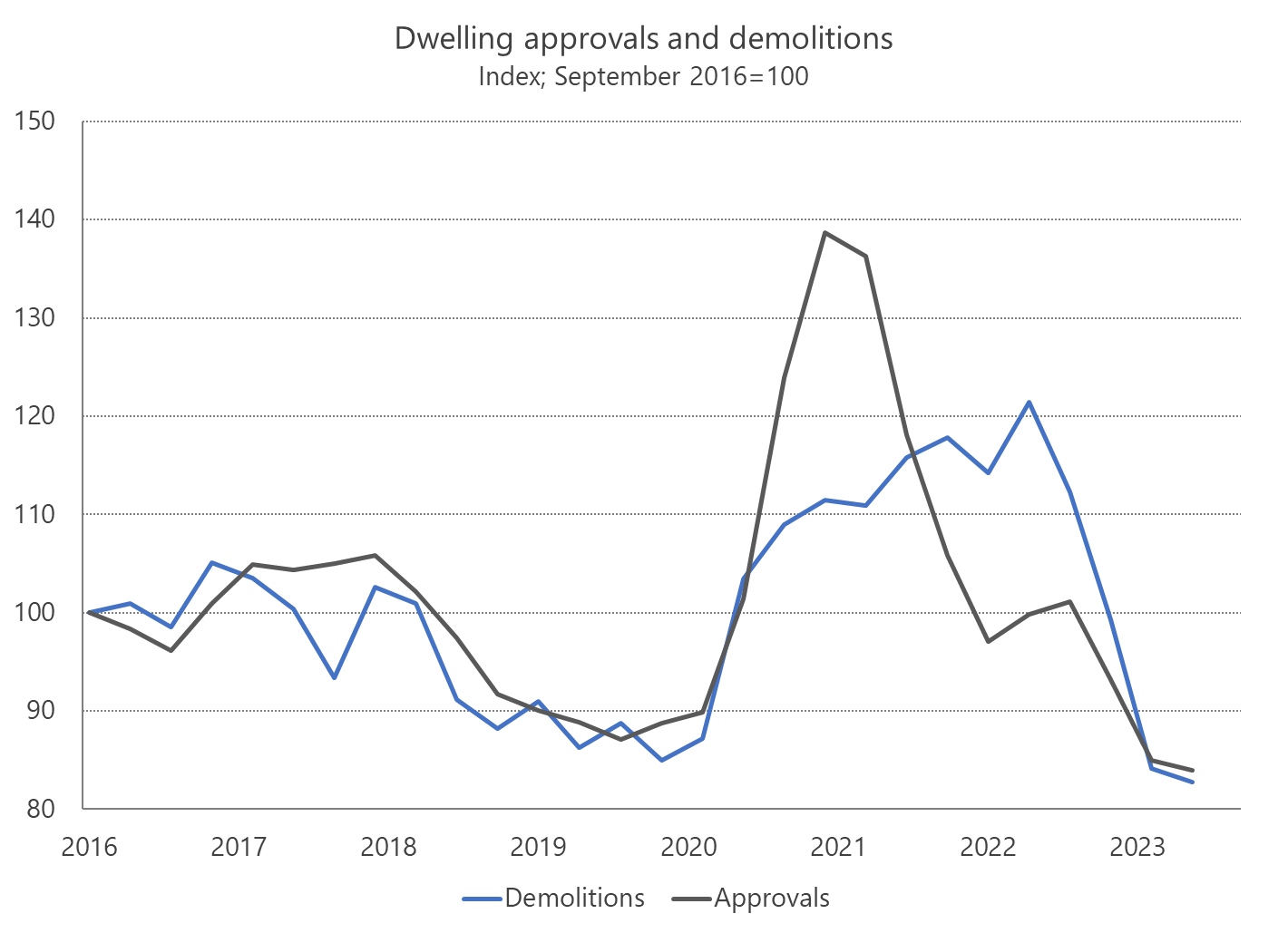

The reason why housing – and especially rentals – have been hit especially hard with price rises is largely because of the lagged effects of government policy. From June 2020 until April 2021, the federal government was offering large grants to owner-occupiers who enter into a contract to build or “substantially” renovate a home. This was matched by most States and Territories, creating a huge incentive for people to knock down their houses to rebuild.

The RBA further aggravated this demand shock by cutting rates to zero, giving banks $188 billion of cheap debt to funnel into mortgages, and engaging in quantitative easing (buying government bonds to reduce borrowing costs). To cap it all off, the Australian Prudential Regulatory Authority (APRA) had already removed its requirements for ‘stress tests’ on mortgage lending, allowing banks to issue people with larger loans than they could pre-pandemic.

People respond to incentives

So, what happened? People responded to these incentives, knocked down their houses, and then needed a rental to live in while it was being built. This effect, combined with the rise of short-term accommodation platforms such as Airbnb, and a desire for more space due to pandemic-related health restrictions and the ‘work from home revolution’, put enormous pressure on the rental market.

When you pay people to knock their houses down, don’t be surprised when they do it.

When you pay people to knock their houses down, don’t be surprised when they do it.

Rising housing costs caused by this government-induced shock are a relative price change; houses have gone up in value compared to most other goods and services in the economy. It has nothing to do with the persistent inflation we’re experiencing today, which is due to fiscal and monetary policy errors. Contra Costello, immigrants and house/rental prices are not “driving inflation”, as higher expenses in that area should mean people have less money to spend elsewhere, causing prices to stabilise or fall in the rest of the economy.

But that’s just not happening, with Australia the worst in the OECD for “inflation dispersion”, defined as “the share of consumer prices across the economy that are rising by more than 2% year on year”.

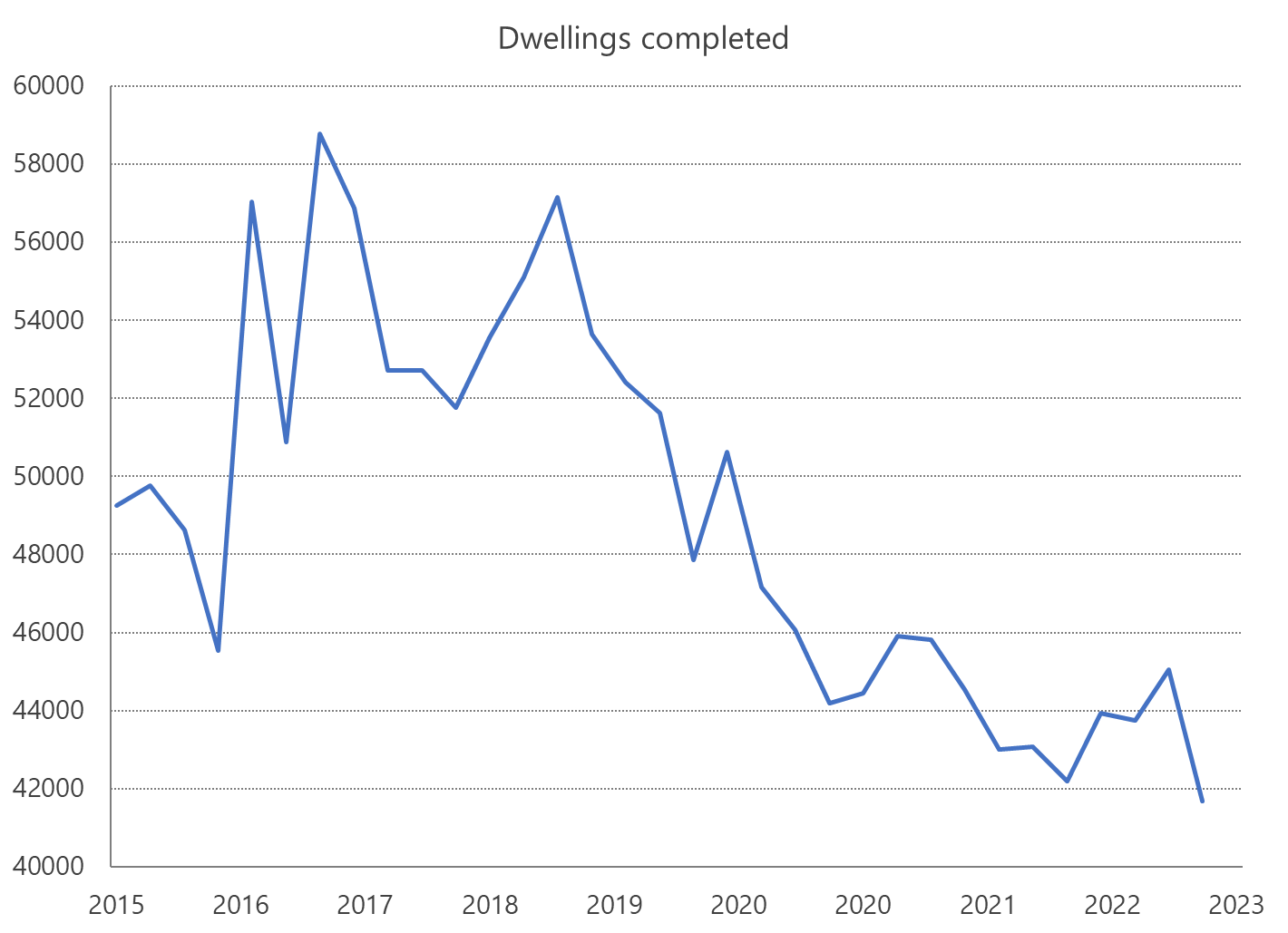

But inflation did make things worse for Australia’s construction sector, and it’s one of the reasons why supply hasn’t been able to quickly respond to the surge in demand. State regulations such as WA’s Home Building Contracts Act prohibit “rise and fall” clauses, which prevent builders from passing on their ever-rising labour and supply costs. These regulations work fine when inflation is low and predictable; but when it’s high and unexpected, the industry struggles to build adequate buffers into its’ contracts. The fixed-price nature of the industry is one reason why we see builders failing on a weekly basis, and also a reason why the stimulus-driven houses aren’t being completed – builders “prioritised these new, profitable jobs to effectively pay for these loss-making jobs”.

How immigration fits in

When you screw up a market as much as our local, state and federal governments did, and then you quickly add a large number of immigrants who need to live somewhere into the mix, it’s probably not going to make it any better. The housing market was badly distorted even before any immigrants arrived – remember that population growth went nowhere for a couple of years when our borders were closed. Given the state the housing market is in, even catch-up population growth is likely to exacerbate the situation.

Unfortunately, there are no easy answers that will fix the mess in the short run. Immigrants are needed – unemployment is close to record-lows, suggesting businesses are clamouring for workers who might help ease some of the supply constraints holding up construction – and while we desperately need to build more housing, zoning reform takes time (+political buy-in) and so too does physically erecting the things.

And we haven’t been very good at that in recent years.

Despite huge demand, we haven’t been able to complete much new housing.

Despite huge demand, we haven’t been able to complete much new housing.

The ongoing housing and rental crisis will take time to resolve. Immigrants might prove to be an easy scapegoat, but they’re not why our housing market is in the mess it’s in today, and they’re also not making inflation worse. The best thing local, state and federal governments can do from here to fix the crisis is clear the artificial barriers holding up construction and let us build.

Comments

Comments have been disabled and we're not sure if we'll ever turn them back on. If you have something you would like to contribute, please send Justin an email or hit up social media!