Don't mistake a majority for a mandate

The Anthony Albanese-led Labor party won convincingly at the recent federal election, picking up a whopping 94 seats, 17 more than in 2022. That gives it a massive majority: there are only 150 seats in the House, and Labor now holds nearly two-thirds of them.

Understandably, certain individuals—including the Prime Minister himself—have said that means Labor has a clear “mandate”; that it has the electorate’s permission to push forward with the policies it took to the election:

“I do want to thank the Australian people for the very clear mandate that they’ve given my government. Today, we continue the work of continuing to build Australia’s future.”

It’s not a view held only within the Labor party. Here is Liberal member for Goldstein, Tim Wilson, discussing a “mandate” for a specific policy:

“Labor has a mandate for its tax on unrealised capital gains, so its passage is now intertwined with the survival of this government itself.”

Contra Albanese and Wilson, in a democracy like Australia it’s rare that a ruling party has a clear mandate, whether for all of its policies or even a single one.

Yes, Labor won a big parliamentary majority. But the primary vote swing in its favour was just 6% (1.98% percentage points), leaving Labor with 34.56% of the vote—so, favoured by a touch over a third of Australian voters.

What that tells me is a full two-thirds of Australians didn’t like Labor’s policies enough to give them their first preference. The Liberal–National Coalition, which ran an awful campaign and was obliterated at the election, still picked up 31.82% of primary votes—only around 440,000 (2.4% of registered voters) fewer than Labor. But no one would dare claim that they have a mandate!

The will of the people is hard to define

I reject the entire concept of a political “mandate” in modern Australia, for two main reasons.

One, people aren’t voting for single issues but packages of policies. Some they like, some they don’t. If your party’s package has just a single policy a voter likes and 99 policies they dislike, but your main opponent has 100 bad policies, you’ll still win—but don’t go pretending you have some kind of “mandate”!

In the context of the 2025 election, there’s no question Labor was helped by Donald Trump and a Peter Dutton-led Coalition that couldn’t produce a coherent policy agenda. In fact, Labor was trailing in the polls and on prediction markets for several months in the lead-up to the election: does that sound like an electorate brimming with confidence in your policy platform? Hardly.

Two, the idea of a popular mandate assumes there’s a clear way to aggregate voters’ preferences—but that’s not how democracy works in practice. Arrow’s impossibility theorem demonstrated that when voters rank three or more options, no ordinal voting system (linear ordering of candidates) can fairly reflect the “will of the people” without pitfalls.

Australia’s preferential voting system—where the candidate with the fewest votes is eliminated round-by-round, with their votes redistributed based on the next preferences listed—does a good job at covering most bases. But it can still violate the independence of irrelevant alternatives, and the risk of doing so grows along with the share of votes going to independents and minor parties.

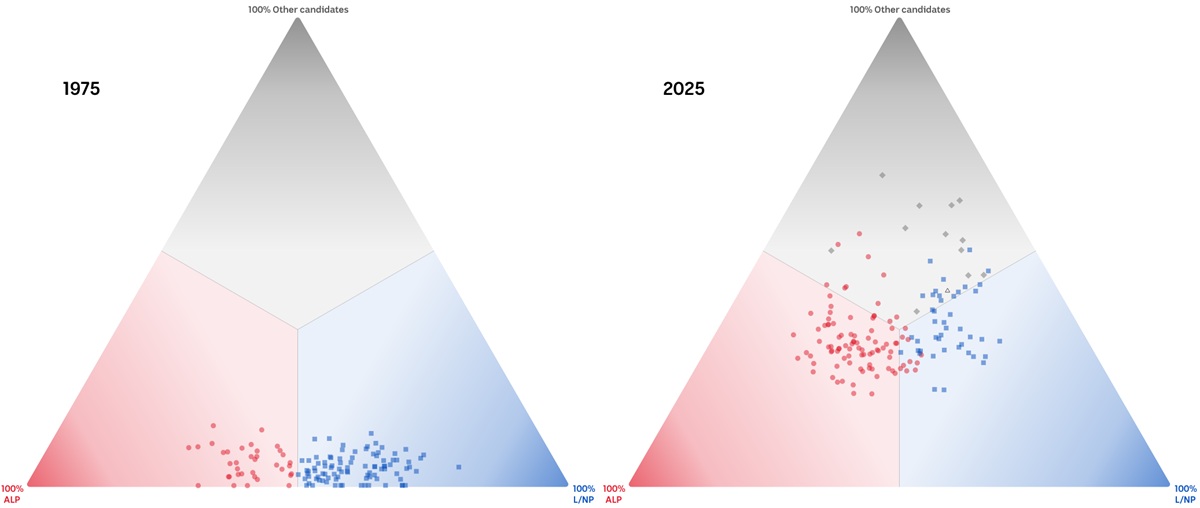

There’s a strong trend in Australia for voters to shun the two major parties in favour of independents. In the 2025 election, the “other” vote was around two percentage points higher than it was in 2022. But it was more than double the 2007 vote, and nearly eight times what it was in 1975:

As the number of candidates at the top of the triangle grows:

- The number of possible elimination paths increases.

- Small differences in primary votes can have outsized effects.

- The mere presence of another candidate—even if they have little support—can shift the final outcome.

In other words, as the two-party system breaks down and people increasingly vote for independents and minor parties, preference flows and elimination orders increasingly shape who wins, rather than clear majority support, undermining any claim to a “mandate”.

So while Labor might have a strong parliamentary majority, it’s not even close to having a popular majority, or the “will of the people”. Indeed, Australian voters now tend to deliver something that more closely resembles a least-bad outcome rather than a mandate. If politicians don’t recognise that, then they risk being bounced at the first opportunity.

The mandate trap

If Anthony Albanese thinks he has a “mandate”, then he’s at risk of falling into the same trap that befell former Labor leaders such as Gough Whitlam. Here’s the University of New England’s Graham Maddox on the demise of Whitlam, a Prime Minister who would frequently use the word mandate “to browbeat the opposition for undermining and obstructing” his agenda:

“The fact is that not only has the ‘mandate’ fallen into theoretical disrepair, but it has also been eschewed by both sides of politics as they adopt a so-called ‘small target’ approach to electioneering. After Whitlam’s electoral disasters in 1975 and 1977, the Labor Party sought to distance itself as far as possible from the dead weight of the Whitlam legacy. As Andrew Scott shows in his contribution to It’s Time Again, it became a scandalously cheap form of abuse within the Hawke government to brand anyone with an ambitious program for positive action and public spending as an ‘unreconstructed Whitlamite’. There is much controversy as to whether the post-Whitlam stance of the Labor Party marked a radical change of direction, but the abandonment of the grand, mandated program is indisputable.”

Of course, Whitlam had plenty of other flaws besides his bulldozer-like approach to policy-making under the guise of a mandate. But as former ANU professor John Uhr wrote, Australia’s bicameral dynamics, with an elected equivalent (the senate) performing the role the UK’s House of Lords used to play, means the mandate model doesn’t even apply here:

“The misleading model of ‘mandate’ is drawn from the British parliament at Westminster, where the mandate theory developed in the pre-First World War struggle between the House of Commons and the unelected House of Lords. The irony is that it was the Lords which foolishly taunted the Commons with the charge that a range of contentious government bills on social policy lacked a mandate. The Commons successfully curtailed the power of the unelected Lords to obstruct government bills, and adopted the strategy of claiming a mandate for every contentious bill… Mandate theories derive from the inter-cameral disputes of Westminster, and seem an inappropriate response to the realities of parliamentary power in Australia.”

There’s no question that Labor won the election and is therefore free to pursue whatever policies it wants. But achieving 34.56% of the popular vote doesn’t give you a “mandate” to cut yourself a policy blank cheque.

If Albanese leans too heavily on the notion of a mandate, he risks repeating Whitlam’s fatal overreach—governing as if he speaks for more voters than he actually does. The Australian electorate is much less forgiving to second-term governments, and they won’t appreciate being taken for granted under the guise of a non-existent “mandate”.

Comments

Comments have been disabled and we're not sure if we'll ever turn them back on. If you have something you would like to contribute, please send Justin an email or hit up social media!