False prophets, forward guidance, and failed lessons

Last week, the Reserve Bank of Australia’s (RBA) deputy governor and governor made what I can only describe as deliberately bold and somewhat contradictory statements about accountability, uncertainty and what it all means for monetary policy. I’m not sure how they missed the contradiction, and it worries me that they may have learned very little from the experience of the past few years.

Anyway, first up was deputy governor Andrew Hauser, who used his second speech in eight months on the job to rip into the media with a provocatively titled piece called Beware False Prophets:

“Of course, eye-catching language sells newspapers, secures clients and draws crowds to the soapbox. But when the stakes are so high, claiming supreme confidence or certainty over what is an intrinsically uncertain and ambiguous outlook is a dangerous game. At best, it needlessly weaponises an important but difficult process of discovery. At worst, it risks driving poor analysis and decision-making that could harm the welfare of all Australians. It is right to want to be confident that the central bank will bring inflation back to target and maintain full employment: that is the RBA’s mandate, and we should be held to account for it. But the policy strategy required to deliver that outcome, and the economic judgements that inform it, simply cannot be stated with anything like the same degree of certainty. Those pretending otherwise are false prophets.”

I generally agree with that sentiment, although it’s a bit hypocritical; the Review of the RBA found that its staff demonstrated “insularity, arrogance, and over-confidence”, and the RBA has on many occasions engaged in precisely the behaviour that Hauser accused others of doing. Recall that former governor Philip Lowe claimed, at least three times over the course of 2021, that he was going to hold firm on rates until 2024 – only to start hiking in May 2022.

A little introspection would have been nice.

But back to the speech, which brings into question a lot of what the RBA itself says and does publicly. For example, it publishes regular forecasts, the most recent of which goes out to the end of 2026. But why bother? Governor Michelle Bullock basically says they’re rubbish, with “substantial uncertainty around them, more so the further out the forecasts are”.

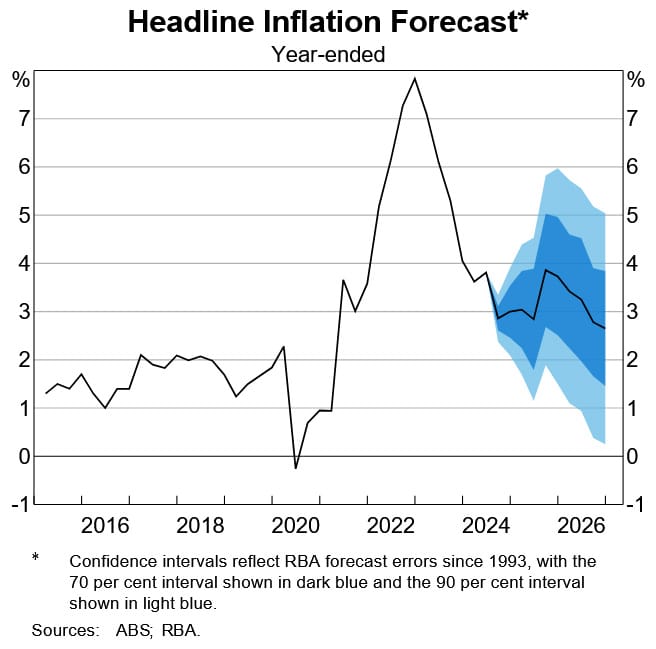

Unlike elected governments, the RBA doesn’t need to cost election commitments over the forward estimates. And central banks struggle to foresee three months into the future, let alone nearly three years. It’s why charts like this from its recent outlook have such huge errors bands in both directions:

The RBA also talks too much in its attempt to manage expectations – what it calls “forward guidance”, or the attempt to influence financial conditions in the present by speculating about the future. Philip Lowe learned the hard way why that’s such as bad idea, but it didn’t get a mention in Hauser’s speech.

A warning across the ditch

If the RBA needed another example of how forward guidance can be dangerous, the Reserve Bank of New Zealand (RBNZ) was just burned hard by that strategy, and has suffered a serious hit to its credibility as a result:

“Infometrics chief executive Brad Olsen previously said ‘heads should roll’ if a cut happened this week, given the economy had progressed much as the Reserve Bank was expecting it to when it forecast no cut until 2025 [in May].

In its statement, the bank’s only acknowledgement of its changed view was a reference to ‘high-frequency indicators’ pointing to material weakening in activity.

‘The bank seems to have just ignored what it did in May and hope the rest of us forget – we won’t,’ Olsen said.”

Should the RBNZ have cut? Absolutely; New Zealand is in its third recession in as many years, and inflation has come down significantly. The error wasn’t in last week’s decision to cut but in May’s forecast, which “badly misread how the economy was unfolding”.

There really was no excuse; as former RBNZ economist Michael Reddell noted, the central bank was so confident in its position that it ignored the evidence and pigheadedly stuck with what it thought its models were telling it (sound familiar?):

“There has been no nasty external shock in that time (global financial crisis, pandemic, collapse in commodity prices etc) but we’ve gone from a ‘hawkish hold’ (best guess, no easing until this time next year, and possibly some tightening late this year) to not only an OCR cut now, but a really large (at peak 130 basis points) change in the projected forward track for the OCR. I can’t recall another change that large that quickly, in the absence of a major external shock, in the 27 years since the Bank started publishing these forward tracks.”

Central banks need to ditch the forward guidance and other attempts at managing expectations. Maintain credibility by setting monetary policy appropriately, and the expectations will take care of themselves.

The RBA should admit its mistakes

A good way to restore credibility and convince people that your culture has moved on from one of “insularity, arrogance, and over-confidence” is to express humility and fess up to your mistakes. Hauser’s speech stopped short of doing that, probably because one of them cost taxpayers $50 billion and has yet to receive any media attention. But at least he said they’re learning:

“By learning continuously – from our own forecast errors, from diverse quantitative models, from corporate liaison and other qualitative intelligence-gathering, from experience in other countries, and from internal and external challenge, including scenarios and ‘what-ifs’. By communicating clearly and openly about what we don’t know, as well as what we do. And by adopting policy strategies that reflect risks to the outlook, as well as the central case.”

The thing is, it’s one thing to say you’ve changed, but the proof is in what you do. So has the RBA really changed? Lowe’s replacement as governor, Michelle Bullock, started well when back in March she did exactly what Hauser professed, telling journalists that “I won’t be giving forward guidance… we’re not ruling anything in and we’re not ruling anything out”.

Great: everything should be on the table, at every meeting! You just look foolish if you rule out a rate change months from now because your models tell you it’s impossible for inflation to be that high/low. The fact is macro models just aren’t very good: in 2020, they told the RBA that inflation would be below-target until December 2024. Then in 2021, they told the RBA not to worry because even though there’s inflation, it’s all supply-induced so it will be transitory. Only in 2022 when the alarm bells started to flash – at a time when most other central banks were already well into their tightening cycles – did Lowe perform his now infamous u-turn.

Hauser’s speech acknowledged these shortfalls:

“The starting point is to avoid placing too much reliance on point forecasts in the first place, and instead frame our policy decisions in terms of contingent hypotheses or judgements. Some judgements may be strongly held, and hence given a high weight in the decision; others may be very tentative and given only a low weight. Both the hypotheses, and the weights attached to them, are continuously updated through a process of learning.”

The RBA doesn’t have the information it needs to make a clear prediction about six weeks in the future, let alone six months. Hauser is absolutely correct when he concludes that the answer the RBA should give when asked about the future cash rate is “that we simply do not know”.

Unfortunately, recent events have shown that’s not how the RBA works in practice.

Round and round we go

Just five months after saying “I won’t be giving forward guidance”, governor Bullock couldn’t help herself, telling eager journalists keen for a headline that rates would be going nowhere until at least “the end of the year”:

“I think the board’s feeling is that [in] the near term — by the end of the year, in the next six months — that [a rate cut] doesn’t align given what the board knows at the moment and given what the forecasts are.”

Bullock then repeated that to the House of Representatives Standing Committee on Economics last week, saying that it’s “premature to be thinking about rate cuts”.

But… why? Did Bullock even read Hauser’s speech? She seems to have, because she acknowledged it in her own opening statement to the House:

“The key point [in Hauser’s speech] was that we know the future is uncertain and that we therefore need to be humble in our forecasts, be willing to learn from our errors, and use a diverse range of models and qualitative intelligence, as well as internal and external challenge.”

How is it being “humble” to speculate six months into the future? Did the lessons of your former boss, Philip Lowe, teach you nothing? Just don’t do it! Don’t be ashamed to tell the media that that the cash rate will be on hold until 24 September (the next meeting) and after than it depends on where the economy goes between now and then.

Former Bank of England governor Mervyn King, who correctly foresaw the post-pandemic inflationary surge and group-think going on at global central banks, wisely said that:

“The only forward guidance markets and economic agents need is an unswerving commitment to price stability”.

One reason why the RBA has been able to maintain its independence from the government of the day is because it could credibly commit to price stability. Philip Lowe’s RBA damaged that credibility to the point where it’s at serious risk of becoming politicised. If Michelle Bullock continues to provide forward guidance in times of considerable uncertainty, she risks destroying whatever credibility it has left.

Too late and too much

To be clear, I think that it’s perfectly fine for the RBA to believe that rates will be on hold for the next six months. In fact, those sort of views are advisable; as Princeton economist and former vice chair of the US Fed Alan Blinder observed, too many central bankers reject the “dynamic programming way of thinking because they think it both foolish and dangerous to make a multi-period plan when you do not know what lies ahead”.

But it should keep those views in-house. Monetary policy operates with considerable lags, and that’s hard for people – including even central bankers – to comprehend. Here’s Blinder again:

“Put plainly, human beings have a hard time doing what homo economicus does so easily: waiting patiently for the lagged effects of past actions to be felt. I have often illustrated this problem with the parable of the thermostat. The following has probably happened to each of you; it has certainly happened to me. You check in to a hotel where you are unfamiliar with the room thermostat. The room is much too hot, so you turn down the thermostat and take a shower. Emerging 15 minutes later, you find the room still too hot. So you turn the thermostat down another notch, remove the wool blanket, and go to sleep. At about 3 am, you awake shivering in a room that is freezing cold.

The corresponding error in monetary policy leads to a strategy that I call ’looking out the window’. At each decision point, the central bank takes the economy’s temperature and, if it is still too hot (or too cold), proceeds to tighten (or to ease) monetary policy another notch. With long lags, you can easily see how such myopic decision making can lead a central bank to overstay its policy stance, that is, to continue tightening or easing for too long.”

The great monetarist Milton Friedman, in a 1968 American Economic Review paper, wrote that the “general practice” of central banking up to that point been had been a case of “[t]oo late and too much”:

“For example, in early 1966, it was the right policy for the Federal Reserve to move in a less expansionary direction-though it should have done so at least a year earlier. But when it moved, it went too far, producing the sharpest change in the rate of monetary growth of the post-war era. Again, having gone too far, it was the right policy for the Fed to reverse course at the end of 1966. But again it went too far, not only restoring but exceeding the earlier excessive rate of monetary growth. And this episode is no exception. Time and again this has been the course followed – as in 1919 and 1920, in 1937 and 1938, in 1953 and 1954, in 1959 and 1960.”

Friedman put these mistakes down to a failure of central bankers to appreciate “the delay between their actions and the subsequent effects on the economy”, preferring to focus too much on “today’s conditions”.

The RBA can certainly be accused of making both mistakes. It did “too much” monetary easing in 2020, and then was far “too late” to unwind it, waiting until 2022 when inflation was already well and truly out of hand.

Today, the cash rate has been on hold for nine months and if Bullock is to be believed, it will stay there for at least another six. That’s a long time for monetary policy; as former US Fed chair Janet Yellen observed, central bankers should " be wary of moving too gradually… we want to be ahead of the curve and not behind it".

Fifteen months is more than enough time for the lagged effects of the RBA’s tightening to start showing up in the data. The problem with that is that by the time the RBA notices and starts cutting rates, it will probably be “too late” and end up doing “too much” in an attempt to offset its mistakes from several months earlier.

The RBA creates its own false prophets

The reason there are so many “false prophets” out there is because the RBA operates with pure discretion, and has repeatedly demonstrated that its word is worthless. Bullock can say rates will stay where they are until the cows come home, but it’s completely meaningless because everyone who lived through 2022 knows that the RBA can’t be trusted. It’s the perfect ecosystem for false prophets to thrive: people are looking for answers and they know the RBA isn’t going to give it to them.

So, what can be done? Sadly, nothing. The Review of the RBA basically recommended, in the grand scheme of things, relatively minor governance changes; the RBA will continue to operate with full discretion to achieving its dual full employment and stable inflation mandate. But that’s precisely how it got us into the current mess in the first place – the desire to tolerate above-target inflation for longer than it should to “preserve the employment gains of recent years in a sustainable manner”:

“We did not increase interest rates as much as some other central banks. And we have received some criticism for that. Indeed, some commentators continue to call for further tightening in monetary policy. But as I noted earlier, we have been trying to balance bringing inflation back down over a reasonable timeframe, without inflicting unnecessary damage on the labour market. And the Board’s judgement to date has been that policy is currently sufficiently restrictive to do that.”

The problem is that not everything can be fixed with monetary policy; like most economic problems, employment is a real variable that can only be manipulated in the short-run, and so is best left to policymakers. Inflation, however, is a nominal variable that can be targeted in the medium- to long-run.

My view is that so long as the RBA’s dual mandate remains in place – which the recent reforms mistakenly strengthened – it will continue making mistakes by trying to “balance” employment and inflation, instead of focusing solely on the only variable it can control: price stability. And the more mistakes it makes, the more false prophets it breeds and the greater the risk politicians – who will always interpret the mandate in a way that considers maximum employment as the primary goal – will also start to exert their influence on it.

Ultimately, the best way for the RBA to credibly commit to low inflation is to achieve it. It doesn’t expect to do that until 2026, which is perhaps why the governor and deputy governor have been so critical of “false prophets”, and have started issuing forward guidance again to try to anchor expectations. But they can talk as much as they want; actions speak louder than words, and until they convince people that they’re actually in control of inflation above all else, then inflation expectations will remain inadequately anchored, false prophets will flourish, and they’ll forever be missing targets and making mistakes.

Comments

Comments have been disabled and we're not sure if we'll ever turn them back on. If you have something you would like to contribute, please send Justin an email or hit up social media!