Friday Fodder (13/24)

1. Why we hate inflation

Robert Shiller, who won the Nobel prize in Economics back in 2013, penned a famous essay in 1997 called Why Do People Dislike Inflation ? Shiller’s conclusion was that inflation affects people beyond its economic costs, including because it undermines their living standards, fosters a distrust of government – “a feeling that opportunities for profit through deception are being willingly created” – and undermines the “national prestige” that comes with high inflation and weak exchange rates.

Last week, Harvard’s Stefanie Stantcheva published a draft paper that takes a “fresh perspective on the enduring question of why people dislike inflation, incorporating significant advancements in survey methodology that have occurred since the 1990s”. Stantcheva found that today people dislike inflation because of:

- the “erosion of purchasing power”, particularly among lower-income individuals who find themselves altering their spending habits;

- “a widespread perception of inequality exacerbated by inflation, as respondents believe that high-income earners’ wages increase more rapidly in inflationary periods”; and

- “stress and emotional reactions, reflecting another potential personal and societal toll of rising prices”

Interestingly, most people had no real idea as to the actual causes of inflation, with “political affiliations influencing whether individuals blame the government, businesses, or broader systemic factors”.

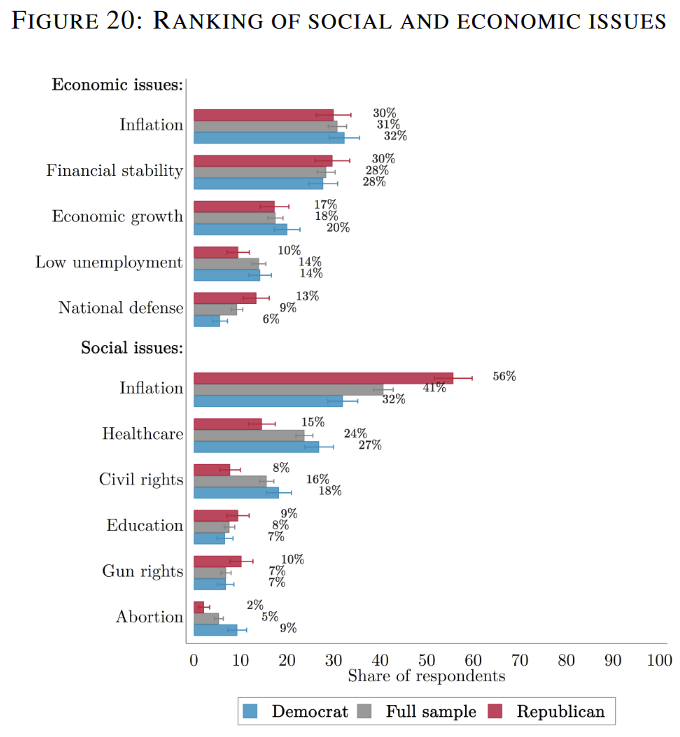

Very few people recognised potential trade-offs of inflation such as lower unemployment or economic growth, with a “a consensus on the lack of positive outcomes from inflation… making it a high priority for policy action”. In fact, inflation is the most hated of all social and economic issues:

There you go: twenty-seven years later and the public’s opposition to inflation remains, for good reason. If the Albanese government wants to be re-elected in 2025, it should stop its deficit financed fiscal stimulus which is only making our inflationary problem worse.

2. Bayesian reasoning and the Wuhan lab leak

A guy called Saar Wilf, an ex-Israeli entrepreneur, came up with a way to try and weigh up the balance of probabilities and make predictions about various global events. Whether Putin has cancer, an Israeli murder mystery, whether Vitamin D helps against COVID-19; these are all topics investigated by Saar. It’s all fascinating, given how valuable Bayesian reasoning is in the real world but also how hard it is to pull off. So writes Scott Alexander:

“Nobody - not the statisticians, not Nate Silver, certainly not me - tries to do full Bayesian reasoning on fuzzy real-world problems. They’d be too hard to model. You’d make some philosophical mistake converting the situation into numbers, then end up much worse off than if you’d tried normal human intuition.”

But Saar thinks his model is great. So great that he offers a $100,000 bet for anyone who takes the opposite side. Enter Peter Miller:

“At the time, I had no idea who Peter was. I kind of still don’t. He’s not Internet famous. He describes himself as a “physics student, programmer, and mountaineer” who “obsessively researches random topics”. After a family member got into lab leak a few years ago, he started investigating. Although he started somewhere between neutral and positive towards the hypothesis, he ended up “90%+” convinced it was false. He also ended up annoyed: contrarian bloggers were raking in Substack cash by promoting lab leak, but there seemed to be no incentive to defend zoonosis.”

Peter and Saar agreed on two judges, then proceeded to debate their respective cases, which you can watch (or read) in full on Scott’s website. All fascinating stuff, and I won’t reveal any more other than to say that there were a few heroic assumptions, a bit of pseudoscience, some dodgy maths, expert debate, a “totally new kind of human suffering, worthy of Shakespeare”, and in the end, a “decisive victory”. Yes, there was even a prediction market on who would win.

3. The urgent need for economic reform

Michael Read, the AFR’s Economics correspondent, reported on a stark finding from investment bank Jarden earlier this week: that “almost one in three jobs created over the past year was in an industry servicing the ballooning National Disability Insurance Scheme”:

“The growth in publicly funded employment has masked the slowdown in the private sector jobs market, Jarden economists Carlos Cacho and Anthony Malouf said.

The findings, which use data from the monthly labour force survey, mean that NDIS-related work accounted for 30 per cent of annual employment growth, despite representing just 6 per cent of jobs.

While workers in these jobs could also be employed elsewhere in the care economy, Mr Cacho said the main driver of the growth was the “blowout” in funding for the NDIS.”

World-leading inflation (amongst advanced economies). A per capita recession. Rising debt. Increasingly unaffordable housing. Now throw in a strong labour market that looks to be the result of government-induced demand, not private sector dynamism, and suddenly we could be in a bit of trouble. If you missed it, this was my take when I saw these data last month:

“Households are getting by, whether it’s by changing employers, working more hours, or even picking up a second or third job.

[But] don’t get me wrong; that’s not a sign of a healthy economy. Quite the contrary, in fact – we’re having to work more hours to offset declining productivity and living standards. Additionally, many of the jobs created in our historically strong labour market were in government and related sectors, such as health care, social assistance, education and training, which accounted for two-thirds of jobs growth in 2023. Those are of course important jobs, but they’re not all that productive or market-orientated, suggesting that the private sector is struggling.

Which brings me to my final point on wages: the risk for Australia is now stagflation (low growth and high inflation). NGDP growth at around 4.5%, combined with the lagged effect of nominal wage increases locked-in over multiple years (e.g., the NSW construction union is pushing for an unprecedented 26% increase over three years), could see measured inflation become ‘sticky’ at the same time as economic growth slows.

In such an environment, the RBA will struggle to justify rate cuts for fear of entrenching inflationary expectations even further, potentially condemning us to years of insipid growth in the absence of impactful economic reform.”

The Albanese government’s planned NDIS reforms can’t come soon enough.

4. How to reduce debt, Jamaica style

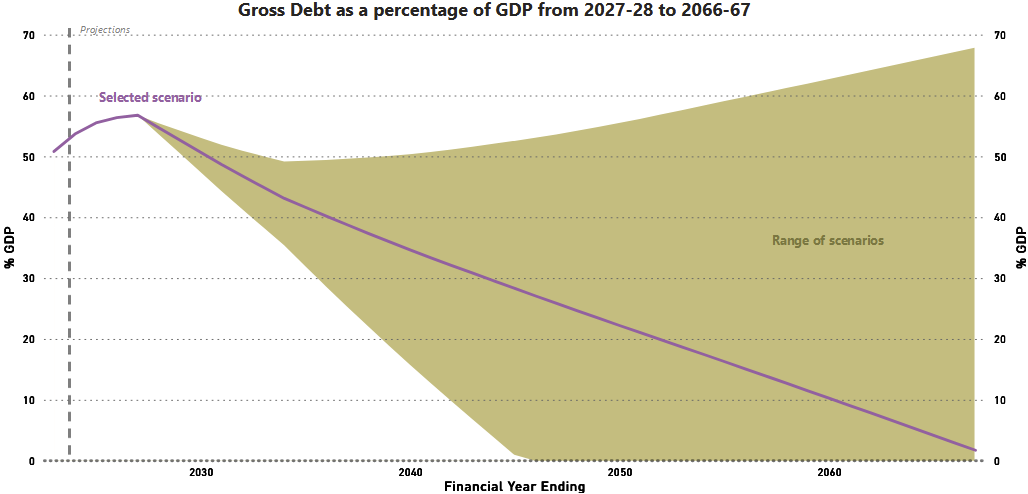

According to the Parliamentary Budget Office, Australia’s gross national government debt is projected to increase to nearly 60% of GDP by 2026-27, then start to decline, assuming our governments engage in “prudent fiscal management”. The range of scenarios is huge, reflecting uncertainty about rates of growth, interest rates, and budget balances.

The purple line assumes 4.5% NGDP growth, 4.7% interest rates, and a 1.2% budget balance.

The purple line assumes 4.5% NGDP growth, 4.7% interest rates, and a 1.2% budget balance.

Currently, only two jurisdictions – WA and the NT – are forecasting a decline in net debt by 2026-27, and only on an underlying basis (i.e. excluding their off balance sheet “investments” that may or may not pay off). Let’s just say that continues and our national debt doesn’t just rise, but starts to increase above the PBO’s upper bound. So what should a policymaker who wants to credible reduce Australia’s debt burden do?

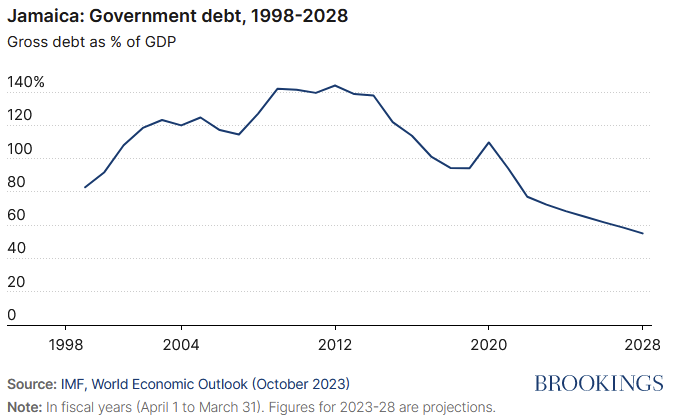

Thankfully a new paper released last week looked at the case of Jamaica (along with Ireland, Barbados, and Iceland), which was – and compared to Australia, still is – an economic basket case. Gross debt to GDP peaked at nearly 145% in 2012, so double the PBO’s worst case for Australia. But Jamaica managed to pull itself out of that quagmire:

How? By adopting fiscal rules, and creating a partnership agreement between opposing political factions “which fostered a common belief that the burden of debt reduction would be widely and fairly shared”:

“The authors conclude that partnership agreements such as in Jamaica are most likely to be achieved in smaller countries where it easier to bring relevant stakeholders to the negotiation table. And they are most prevalent in small, open economies dependent on a few economic sectors and thus vulnerable to shocks, making cooperation on fiscal adjustment urgent.”

“Small, open economies dependent on a few economic sectors”. Sound familiar? Should the bottom ever drop out of iron ore, we may well need a similar playbook in Australia – and a leader capable of negotiating and deploying the fiscal rules needed to stem the bleeding, because we all know politicians find it very hard to do so without binding constraints.

5. If you missed it, from Aussienomics

A sticky, stagflationary mess – Australia risks “sticky” inflation if real wages start to outpace productivity, requiring higher rates longer and job losses as businesses start to adjust on the employment rather than not wage margin. Continued fiscal deficits also fan future inflation risks.

Brisbane should sprint from the Olympics – Brisbane should withdraw from hosting the 2032 Olympics. The cancellation costs will pale into comparison to the billions that will be wasted in cost overruns and the creation of underutilised facilities, funds which would be much better spent on other priorities.

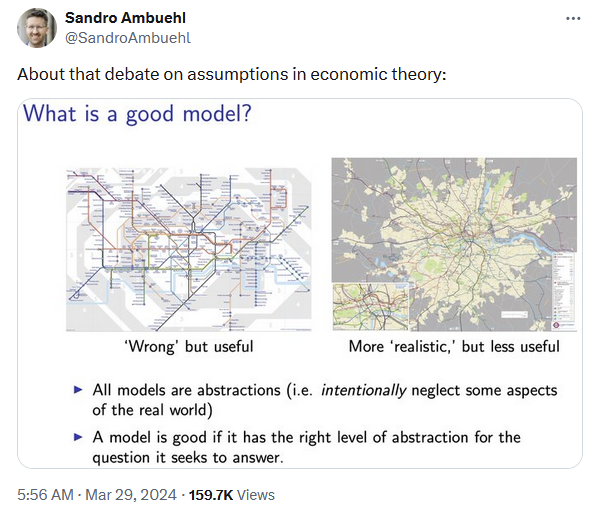

6. BONUS: Even when wrong, models can be useful

Comments

Comments have been disabled and we're not sure if we'll ever turn them back on. If you have something you would like to contribute, please send Justin an email or hit up social media!