Friday Fodder (14/24)

1. Feeling the pinch

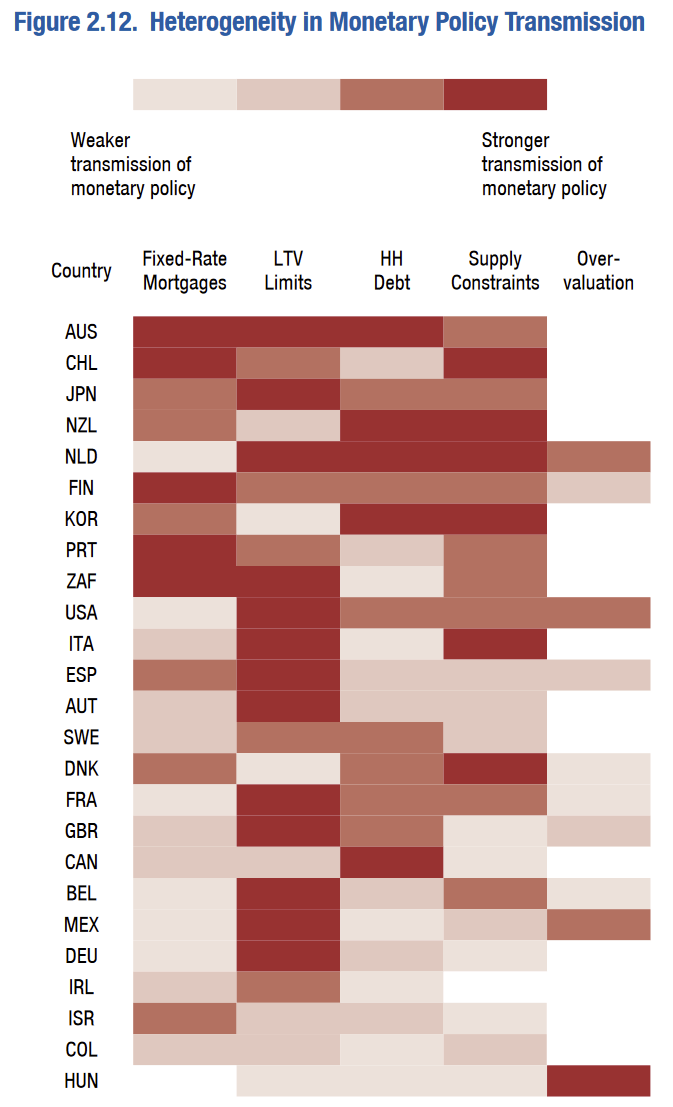

The International Monetary Fund’s (IMF) latest World Economic Outlook (to be released next week) has an interesting chapter on how tighter monetary policy has affected housing markets around the world. It found that:

“Monetary policy has greater effects where (1) fixed-rate mortgages are not common, (2) home buyers are more leveraged, (3) household debt is high, (4) housing supply is restricted, and (5) house prices are overvalued.”

Sounds a lot like Australia, and sure enough, we colour most of the IMF’s boxes bright red:

The bad news is that because we’re so levered into variable rate mortgages in a supply constrained market, we’re more at risk of a “financial crunch” if things go really pear shaped. Tighter financial conditions for indebted households also makes it more difficult to increase our already-insufficient amount of supply, so housing is less likely to become more affordable.

The good news is that rates could come down faster than if we weren’t so fixated on housing: the RBA is well aware that monetary policy transmission in Australia is done principally through mortgage holders, so may err on the side of under tightening rather than over tightening, which may now be the greater risk given these dynamics.

2. More firms doesn’t always equal more competition

The Albanese government released its draft merger reform proposal on Wednesday, which if it goes ahead (there’s a lot of consultation still to be done) will result in more powers for the ACCC:

“The Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) will be empowered and resourced to administer a mandatory and suspensory administrative system from 1 January 2026.”

There’s some good here. For example, mandatory notification and removing duplicative processes. My main concern with the changes is that they seem to conflate competition with industry concentration. For example, under the new “competition test”, it’s simply whether the merger “strengthens or entrenches a position of substantial market power in any market”.

But economists have known for a long time that you can have competitive markets with as few as two firms, provided buyers and sellers don’t face price controls. It’s not clear that having a large number of firms competing in a market is even sufficient for competition, so relying heavily on concentration as a proxy for competition is risky business. Moreover, what I see very little of in the review is whether the outcome of a merger will be efficient. Oliver Williamson showed that depending on the elasticity of demand, even an increase in concentration with higher prices could be beneficial in aggregate because the reduction in costs (allocative efficiencies) created by the merger more than offsets the losses to consumers directly related to the merger.

These laws, if passed as-is, could end up preventing many firms from even attempting mergers at all, because they know they’ll fail the ACCC’s competition test and have to expend considerable resources – at a minimum, $50-100k to pay for the ACCC’s 90-day “investigation” – to finalise any merger. As Williamson warned, “a literal reading of the law which prohibits mergers ‘where in any line of commerce or any section of the country, the effect of such acquisition may be substantially to lessen competition’… run[s] the risk of serious economic loss”.

If these reforms are set up to ignore the realities of competition, which they may well be, then they could end up doing more harm than good.

3. Modi’s policy uncertainty

India has an election starting next Friday, a gruelling six-week process with seven phases, where nearly 1 billion people will be eligible to cast their vote. Up for re-election is 73-year-old Narendra Modi, leader of the conservative Bharatiya Janata Party, and who has been Prime Minister for two terms (i.e. since May 2014).

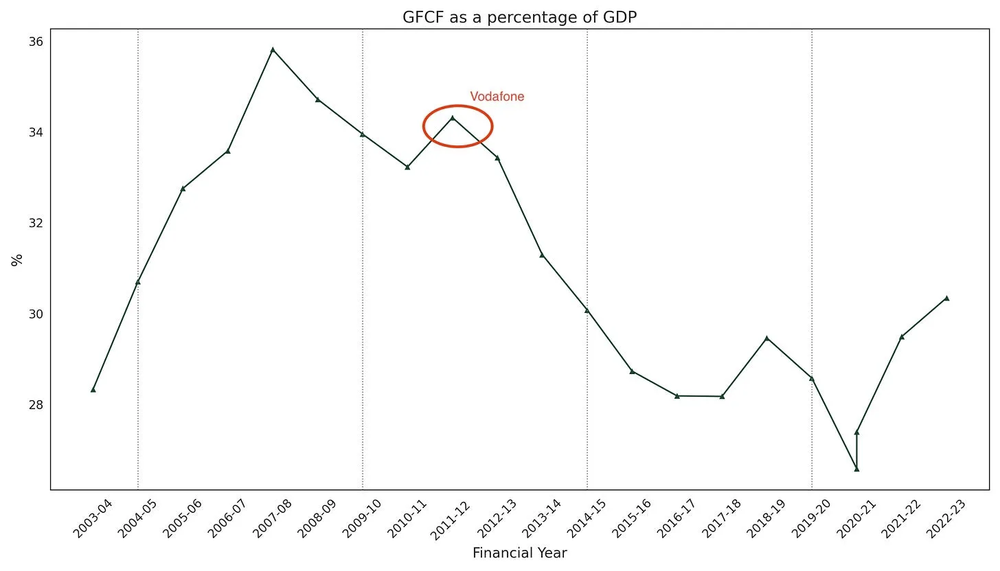

Modi likes to talk up economic development, wanting “to formalise the economy, improve the ease of doing business and boost manufacturing”. But in terms of boosting manufacturing – or encouraging investment – his results have not been stellar:

“While there is no shortage of industrialists praising the Modi government and its economic policies, as a community, they don’t seem to be putting their money where their mouth is. Their reluctance to invest in longer-term plans paints a different picture, one of caution rather than celebration.”

That’s from an essay by Shruti Rajagopalan, who does note that it’s not all Modi’s fault. Just prior to losing power, the ruling party of Indira Gandhi’s “managed to give one last parting gift” to Modi:

“In 2007, Vodafone acquired a stake in Hutchison Essar via an offshore deal. The Indian tax authorities, never ones to miss a party, slapped a hefty tax bill on Vodafone. After zigzagging through courts and appeals, in 2012, the Supreme Court of India held in favour of Vodafone that no taxes were owed in this offshore deal between foreign entities.

Enter Pranab Mukherjee, stage left. In a move that would make his fellow Comrades proud, he amended the Income Tax Act to ensure these transactions were taxable, not just in the future, but with retroactive effect all the way back to 1962, sidestepping the Supreme Court’s verdict. This wasn’t just moving the goalposts; it was declaring a new game had started decades ago, where only the red team won.

And Vodafone was not the only victim, there were others, like UK’s Cairn Energy. Suddenly, investors found themselves navigating a landscape where today’s rules might not apply tomorrow, and deals completed under a past set of rules were fair game for taxation, a scenario no one could have, or indeed did, foresee. The result? Investors, whether parked domestically or eyeing India from abroad, dropped India like a hot potato when it came to big, difficult to undo, long-term bets.”

Investment collapsed:

Mukherjee is gone, but Modi’s government has not done enough to fix India’s institutions to reassure investors that it won’t happen again. In fact, according to Shruti “the last ten years have been mired in a lot of policy uncertainty, usually by the Modi government’s own doing” (remember in 2016 when he tried to wipe out cash almost overnight? Yeh…).

Modi’s next term – his party is expected to secure a majority – will need to improve India’s institutional environment if India is to be the world’s “new ray of hope”, as Modi claims it is.

4. None of the above

Tasmania’s recent election delivered it yet another strongly divided Parliament, with voters shunning the major parties in favour of independents and minors such as the Jacqui Lambie Party (JLP) and the Greens:

“The Liberal party faces having to negotiate with an expanded crossbench to hang on to power in Tasmania after winning the biggest share of the vote in the state election, but falling short of a majority of seats in parliament.

…

The Labor opposition, led by Rebecca White, failed to benefit from the slump in support for the government, rising only marginally to 29.2%. Instead, voters swung to minor parties and independents, which shared nearly 34% of the vote.”

Together, the independents, JLP and Greens have more seats (11) than the opposition Labor party (10), creating a powerful crossbench.

But what does it all mean? The Liberals can of course govern: they just have to compromise with those crossbenchers, honouring the result of the election. So writes Tim Dunlop, who recently looked at the unique political situation in Tassie and the lack of interest in the two major parties:

“What the people are saying is that they want political parties—the broad political class—to lean into that tradition of innovation and reform our institutions to make minority government work— or at least [be] viable—rather than dig their heels in and pretend nothing has changed.

The fact that the major parties are taking the latter course tells you everything you need to know about why their support is deliquescing.”

Tim thinks parliamentary reform is the answer to the voters’ preference, at least in Tassie, to break up the Liberal/Labor oligopoly on power:

“I would contend that there is a huge electoral bonus waiting for whoever is first of Labor or the LNP to accept the new three-party dispensation rather than pretend it isn’t happening. If one of these dinosaurs actually read the writing on the wall, got over themselves, stopped being so contemptuous of the voters who are consistently delivering expanded crossbenches, that party is likely to endow themselves with a long reign as the hub of an ongoing coalition.”

But is that likely to happen? Tim reckons the opposite is more likely:

“I suspect, though, that instead of risking—as they would see it—a diminishment of their own power within the current system that would come from leaning into a multi-party system logic, they will instead try and rig the system against independents and smaller parties.”

I agree; Dan Andrews did it in Victoria with such success that the state now has no independent members. If the crossbench gains power in other states, or federally, it’s hard to fathom the Liberals or Labor doing anything but trying to preserve the status quo. It’s just too good of a deal for them than an alternative coalition model under which they would have to try a bit harder to be accountable to voters.

5. If you missed it, from Aussienomics

Why Australia should stop digging into industrial policy – The Albanese government’s “new approach” to industrial policy is simply mid-20th century interventionism with a lick of green paint. It is wasting money on uncompetitive industries and creating a reliance on subsidies that are politically difficult to remove, burdening consumers and taxpayers.

Can Xi Jinping rescue China’s economy? – China’s economy faces structural issues that Xi’s policies can’t fix. His “new quality productive forces” strategy will distort the economy and fail to make China rich. To stay ahead, Australia should embrace China’s subsidised exports to benefit consumers while ensuring economic flexibility.

Comments

Comments have been disabled and we're not sure if we'll ever turn them back on. If you have something you would like to contribute, please send Justin an email or hit up social media!