Friday Fodder (15/24)

1. Amateur hours

You may have seen Greens Senator Nick McKim questioning the outgoing CEO of Woolworths, Brad Banducci, at a hearing into supermarket prices this week. If you haven’t, I would give it a miss. Even if you know nothing about finance, it’s pure cringe; a blatant attempt at a gotcha moment being orchestrated by someone who either doesn’t know what he’s talking about, or does but gives no shits because… well, politics.

That’s not to say that Banducci came out looking any better. To summarise, for over two hours McKim asked Banducci thirty-nine times to cite Woolworth’s latest return on equity figure. Banducci said he didn’t know, so didn’t answer, eventually taking the question on notice.

McKim made this out to be a huge deal – threatening Banducci with jail and of “bullshitting your way through the committee”. And yes, Banducci absolutely should have had all of his financials handy; this wasn’t his first poor performance under questioning, after all, and is one reason why he won’t be CEO for much longer.

Yet Woolworths is a listed company and everything is available online. McKim clearly had the figure in front of him but chose to engage in political grandstanding instead of, I dunno, not wasting everyone’s time and money.

But perhaps the most embarrassing part of the whole exchange is that return on equity isn’t even a great measure for comparing profitability, mostly because it can be distorted in various ways (such as with debt). As well-briefed Coles CEO Leah Weckert said after Banducci’s grilling:

“I would highlight that equity is a historical number, so it is actually quite difficult to compare return on equities across business.

[For example] if you bought a house 30 years ago, the equity on that would be much lower than if you bought a house ten years ago.”

Weckert also explained to McKim, who was seemingly obsessed with return on equity because “he had become aware that Woolies’ return on equity was two and a half times larger than that of the Australian banks” (and every good Greens Senator knows the banks are pure evil, right?), that there are crucial differences between the two industries, including that banks “are required to hold higher levels of equity, and thus have lower return on that equity”.

International comparisons of return on equity are also tricky. For example, Weckert informed McKim that because the UK’s Tesco owns a lot of land, its return on equity is lower than Coles’, even though its profitability may not be:

“They would hold equity against those buildings and those pieces of land on the balance sheet. As we don’t own those assets, we don’t hold equity on the balance sheet… therefore the denominator we’re dividing by here is lower and so you end up with a higher [return on equity].”

The fact is Coles and Woolworths (‘Colesworth’), while dominating the domestic market with around a 60% share (a figure that excludes growing competitors such as Amazon), are not very profitable businesses. Their net profit margins have been constant at around 2.6% over the past few years, which is hardly indicative of price gouging or ‘greedflation’. Australia’s supermarkets actually have a lower return on investment than their overseas peers, in part because:

“Australia is a big country, sparsely populated, relatively small by global standards, requires plenty of ongoing investment to keep shelves full and customers happy, and is therefore a more expensive place for a supermarket to do business”.

There are nearly a dozen active inquiries into our supermarkets. No doubt some will call for Colesworth to be broken up, which may or may not be desirable in a country where economies of scale for a couple of companies can be more efficient, and better for consumers, than having additional competitors.

Whatever the outcomes of those inquiries, we should be very careful that we don’t simply replace what works with what sounds good, especially when some of them are being chaired by people like Nick McKim, who appears to be more interested in creating gotcha headlines than producing anything that might actually improve outcomes.

Could our supermarkets be more competitive? Probably. But if we forcibly break up Colesworth without considering the full consequences, just because we don’t like big, bad companies, then we may end up paying even more for our groceries.

2. Lies, damned lies, and statistics

There’s an ongoing replication crisis in social sciences that has shown no signs of abating. Whether it be dodgy statistical techniques, poor data management, or outright fraud, a lot of papers from economics to sociology simply can’t be replicated. A new paper out of Canada looked at 110 papers in leading economic and political science journals and found:

- coding errors in 25% of them, even after “excluding minor issues”; and

- upon re-analysis, 52% of the effects found in the papers were smaller than the original published estimates.

That’s not great, but it could be worse. It turns out that behavioural economist and Harvard professor Francesca Gino, currently on unpaid administrative leave while she defends serious charges of data misconduct, has now also been accused of multiple counts of plagiarism:

“The investigation found that the chapter, titled ‘Dishonesty Explained: What Leads Moral People to Act Immorally,’ borrowed extensively from 10 other works, including academic papers and student theses.”

You couldn’t make that up if you tried.

3. Why productivity (and growth) matters

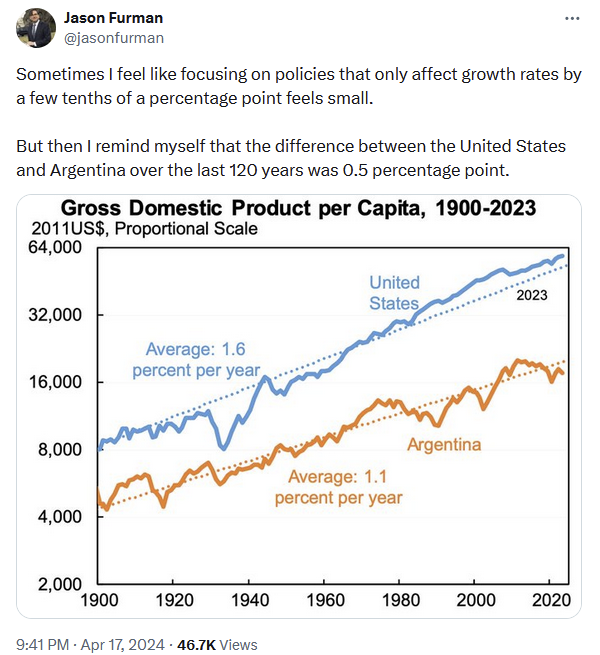

It’s difficult to achieve sustained economic growth without improving productivity, which is also what drives real wages in the long run. Over time, small differences compound:

Robert Lucas ( 1988) said that once you start thinking about economic growth, it’s hard to think about anything else. Policies that add (subtract) from growth may not be noticeable in the short run but over time can add up to significant differences in growth between countries. Productivity boosts growth and real wages, but that’s not all:

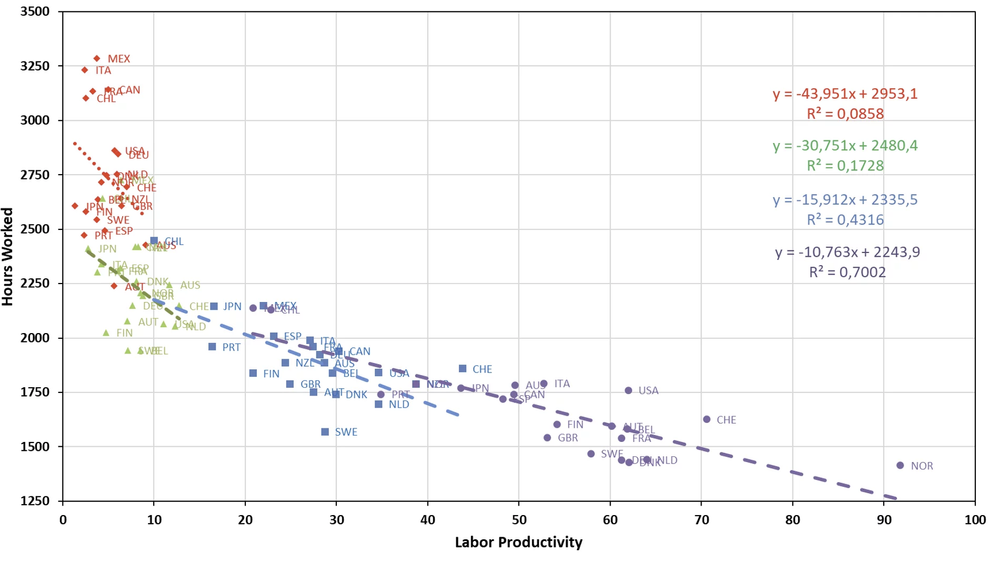

As labour productivity improves, we not only get paid more but also tend to work fewer hours. That’s why in the long run, productivity is almost everything.

4. Manufacturing can’t create enough good jobs

Harvard economics professor Dani Rodrik penned an interesting essay this week on the Biden administration’s Inflation Reduction Act, which despite its name is basically a trillion-dollar play in industrial policy; a much larger version of Albanese’s Future Made in Australia. A key problem, writes Rodrik, is its conflicting goals:

“Then there is the goal of creating good jobs. ‘Sparking a manufacturing, construction, and clean energy renaissance’ is at the very top of the administration’s agenda for building a good-jobs economy. On the face of it, this goal makes a lot of sense. Historically, unionised manufacturing jobs have been the foundation of the middle class. The disappearance of well-paid manufacturing jobs in America’s rust belt and elsewhere – owing to globalisation and technological change – is at least partly responsible for the rise of authoritarian populism.

…

But the fact is that hugely capital-intensive semiconductor plants generate few jobs, relative to the physical investment they require. TSMC’s three fab investments in Arizona are expected to employ a mere 6,000 workers – which works out to more than $10 million per job. Even if the projected tens of thousands of additional jobs in supplier industries materialise, that is a paltry return for employment.”

Jobs also form a key – if not the key – pillar of Albanese’s Future Made in Australia. On Wednesday, after announcing the latest batch of ‘winners’, the Albanese government used the following text in the first paragraph of its media release:

“The Albanese Government will support a further two major critical minerals projects in Queensland and South Australia, helping deliver the building blocks for a future made in Australia while creating hundreds of jobs and opportunities.”

As for the “quote attributable to Prime Minister, Anthony Albanese”, it was more of the same:

“We are building a future made in Australia with secure jobs in our regions. Today we are demonstrating what that means here in Gladstone and in South Australia.

The global race for new jobs and new opportunities is on. Our Government wants Australia to be in it to win it.

These two critical minerals projects will help secure good and secure jobs in manufacturing, and clean, reliable energy.”

Jobs, jobs and more jobs. But as Rodrik makes clear, policies such as the ones being announced by the Albanese government are extremely costly ways of achieving that goal. If you want to create jobs:

“Whether we like it or not, services such as retail, care work, and other personal services will remain the primary engine of job creation. That means we need different types of good-jobs policies, with a greater focus on fostering productivity and labour-friendly innovation for services… rebuilding the middle class, generating enough good jobs, and reinvigorating declining regions call for an entirely different set of policies.”

Spot on. The question now becomes how much money will the Albanese government waste on these projects before it, or a future government, pulls the pin? Removing support for low-productivity, state-dependent businesses can be very difficult to do once they, and their political operatives, are established (just look at our former car industry).

5. If you missed it, from Aussienomics

How can we afford not to? – Australia should resist Albo’s “Future Made in Australia”, which will make all but a few well-connected businesses and workers worse off. Instead, we should focus on boosting industry productivity through reforms such as eliminating trade barriers and zoning restrictions.

AI as a force multiplier – Today’s AI, with its many flaws, is more of a force multiplier than revolutionary tech. Australia should avoid rushing to compete with global leaders in the name of AI sovereignty and instead focus on building guardrails, without being so prescriptive as to kill innovative attempts at AI diffusion.

6. Bonus for paid subscribers: The remembrance of crises past

Shocks, whether it’s war, a pandemic, inflation, or a deep recession, can have long lasting effects on people and their financial decision-making.

That’s according to research by the University of California’s Ulrike Malmendier, who was recently interviewed by David Price of the US Richmond Fed. According to Malmendier:

“After such an experience, you have new data about what can happen. That’s the traditional economic view. But I’d argue that there’s an element beyond the intellectual. When it’s your own life, you tend to put a lot of weight on what has happened to you. You’re pushed toward overweighing outcomes that have happened to you.”

Stock market crashes cause people to avoid stocks for several years. Likewise, inflation causes people to hedge against it in the future, even if the risks of another bout of it have declined:

“If I’m asked to forecast inflation on the margin, I may overweigh what I saw happening; I may overweigh the probability that prices can spiral out of control… I would want to protect myself against inflation. So how can I protect myself? I put my money into protected assets. In addition to gold and the stock market and so on, one way is to invest in real estate. And so one prediction is that people who are worried about their money being worth much less in the future might want, on the margin, to buy a home rather than rent.”

We have just had an entire generation that hadn’t, until 2021, experienced inflation. While the recent slowdown in the rate of inflation means “we might avoid the complete scarring effects”, at the margin it’s still likely to influence their financial decision-making. That has implications for long-run investment and policy, given that Malmendier’s work has shown that these “biases do apply, even to the most successful CEOs”.

And as for the pandemic? Malmendier found that working from home is here to stay, because of “a lasting change in how we view the value of social interaction, the value of working from home versus working at your workplace”:

“[P]ersonally experiencing what remote work and cutting out your commute means for your personal life makes an enormous difference. You have to experience it first, not because of lack of information, not because you cannot add and subtract hours spent in the car versus not, but because it just enters your decision-making differently if you have physically experienced it.”

Comments

Comments have been disabled and we're not sure if we'll ever turn them back on. If you have something you would like to contribute, please send Justin an email or hit up social media!