Friday Fodder (16/24)

1. We should end state overseas offices

As the saying goes, give someone an inch and they’ll take a mile. The latest example of that was Western Australia’s Agent-General for London, John Langoulant, who charged taxpayers “more than $40,000 for the return business class flights… [for] two American getaways with his wife”.

Langoulant’s most recent “official” trips were travel to Germany to farewell the Australian Ambassador and a welcome dinner for the new national representative for the Netherlands. He’s paid more than $840,000 in salary and benefits each year, not including the cost of flights covered by taxpayers for work and personal travel.

Value for money? Hardly. Trade-offs have to be made, and if cutting the state’s foreign offices frees up a bit of cash to pay its teachers without leading to “a situation of other States where they basically bankrupted their States”, then it’s probably one worth making.

There’s no good reason for state trade offices to exist today. For a bit of history, Langoulant’s role was established way back in 1891 (not a typo), shortly after the state was granted responsible government in 1890. These were very early days in the federation, and an agent-general had a few very important tasks. One was to convince the British that the state was a safe place to invest. For example, J. W. Taverner, Agent-General of Victoria, told a London audience that:

“Surely a country where 97 percent are British, your flesh and blood, your language, and under one flag, is a safe spot to invest British capital.”

Another was that, despite achieving independence and passing a constitution in 1901, “affairs conducted in London remained crucial to the administration of Canada and Australia up until the introduction of the Statute of Westminster in 1931, which granted both countries autonomy from the acts promulgated in the British parliament”:

“In sum, the function of agent-general takes its roots in the complexity of colonial governments of the eighteenth century; agents-general was acting as liaison officers, centralising information and coordinating decision-making for the colonies from their London offices. In many cases, the existence of an agent-general was also seen as a status symbol for the colony in question—a position that inferred a measure of influence and clout in the metropolis.

The persistence, not to say survival, of the agent-general function following the development of both the Canadian and Australian federations remains puzzling.”

Today, the role of state foreign offices is officially about “facilitating investment into the State and assisting local industry to access new export markets”. But businesses, including education providers, are more than capable of performing those functions themselves; there’s no reason in an age of fast, affordable travel, not to mention high quality video conferencing, why the taxpayer should be subsidising them.

Really, it’s about status and privilege. The reason these overseas offices persist is because state politicians and their senior bureaucrats – Langoulant was a former Under Treasurer – want an excuse to travel on the taxpayer’s dime, and they want to keep alive the option of a cushy, post-political overseas posting (remember John Barilaro?).

And if the states aren’t willing to end the rort, the Commonwealth could at any time. Section 51 of the Constitution grants the Commonwealth power over:

(i.) Trade and commerce with other countries, and among the States.

(xxix.) External affairs.

State foreign offices are nothing but wasteful relics from another era. The Commonwealth should put its foot down and bring the states into line, as it did when Victoria’s former Premier Dan Andrews pushed the boundaries a bit too far by signing on to China’s Belt and Road initiative.

2. The Zuck on artificial intelligence

Meta (Facebook) CEO Mark Zuckerberg sat down with Dwarkesh Patel last weekend for a very interesting conversation, in which he described why Meta’s approach to AI is different to everyone else’s.

For one, Meta’s latest model, Llama 3, is on-par with market-leading Claude 3 Opus. But unlike Claude and ChatGPT, Llama is open source. Meta is literally spending tens of billions of dollars and then… giving it away. Why, you ask? According to Zuck, because a lot of diverse minds working on a problem can make marginal improvements to the code that swamp the upfront costs:

“We take a lot of the low-level infrastructure and we make that open source. Probably the biggest one in our history was our Open Compute Project where we took the designs for all of our servers, network switches, and data centres, and made it open source and it ended up being super helpful. Although a lot of people can design servers the industry now standardised on our design, which meant that the supply chains basically all got built out around our design. So volumes went up, it got cheaper for everyone, and it saved us billions of dollars which was awesome.

So there’s multiple ways where open source could be helpful for us. One is if people figure out how to run the models more cheaply. We’re going to be spending tens, or a hundred billion dollars or more over time on all this stuff. So if we can do that 10% more efficiently, we’re saving billions or tens of billions of dollars. That’s probably worth a lot by itself. Especially if there are other competitive models out there, it’s not like our thing is giving away some kind of crazy advantage.”

Having been burned by Apple and Google in the smartphone market, Zuck doesn’t want the same to happen in AI:

“Here’s one analogy on this. One thing that I think generally sucks about the mobile ecosystem is that you have these two gatekeeper companies, Apple and Google, that can tell you what you’re allowed to build. There’s the economic version of that which is like when we build something and they just take a bunch of your money. But then there’s the qualitative version, which is actually what upsets me more. There’s a bunch of times when we’ve launched or wanted to launch features and Apple’s just like ’nope, you’re not launching that’. That sucks, right? So the question is, are we set up for a world like that with AI? You’re going to get a handful of companies that run these closed models that are going to be in control of the APIs and therefore able to tell you what you can build?”

Zuck has all the human-facing work already done – Facebook, Instagram, WhatsApp – and Llama will be plugged into those (it already is via Meta AI), which is probably how he intends to monetise it. It will also plug into the ‘metaverse’ he’s building, along with new devices such as Ray-Ban glasses that can now describe what you’re seeing, translate in real time, plus do a bunch of other things your phone currently does – but all hands-free.

Will it work out? I don’t know; investors were certainly unhappy at the additional CapEx and lack of detail on how Meta’s AI investment will generate a return. The competition in the AI space is also fierce, with Apple finally entering the field with device-specific AI (i.e. cloud-free). The only certainty is that this space will continue to rapidly evolve as these firms compete to best satisfy consumers.

3. We can’t build any more

Like it or loathe it, our governments are going full steam ahead with a renewables transmission. But our own laws keep getting in the way:

“The Korean-owned developer [Ark Energy] had planned to clear more than 500 hectares of native vegetation next to the Wet Tropics of Queensland World Heritage Area, home to animals including the koala and magnificent brood frog.

It had been so fiercely contested that the developer was forced to change the name of the project, from Chalumbin to Wooroora, late last year and drastically scale back the number of [wind] turbines from 200 to just 42.

In its email on Friday, Ark Energy said it had received information that the project — which had been in the federal environmental assessment process for almost three years – was unlikely to be given the green light.”

Renewable energy projects have large footprints. Quite often, that means tough decisions have to be made between cutting down some trees or killing a few birds and “clean, green energy”. Or, as in this case, just don’t make a decision at all and eventually the proponent will simply give up.

But what it all means is that we have no chance of meeting our renewables targets:

“According to government figures, it’s taking around 80 weeks, or 20 months, to reach a final decision under the EPBC Act. For the failed Wooroora Station Wind Farm, a final decision was delayed five times.

This often comes on top of the state approvals process that varies greatly.”

Not meeting our renewables target, with no backup plan other than prolonging the life of our aging and increasingly breakdown-prone coal mines (owners are not likely to invest additional capital into plants that have been ordered to shutter), will mean power prices will rise. As Alinta Energy chief executive and managing director Jeff Dimery warned that:

“Australians will have to pay more for energy in the future. We will spend more as a percentage of GDP on energy, energy services and energy infrastructure. Whether we pay through the tax base or pay the large upfront cost of an EV, or batteries and solar, or we are paying more for electricity from the grid – we will all pay more in aggregate. We need to be honest about that, and I don’t think the average Australian is prepared for that reality.”

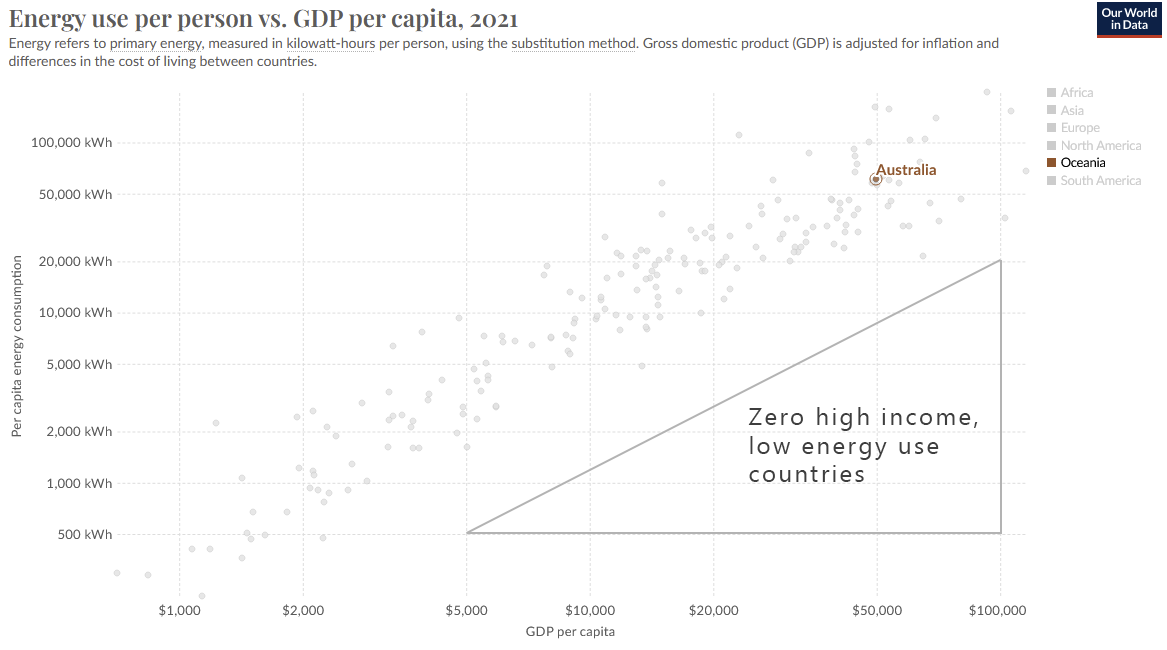

Dimery issued that warning without considering the delays in transitioning; the fact is renewables will cost households more than coal, and we will have to adjust accordingly. On that depressing note, here’s your friendly reminder that no economy has ever become or stayed rich while using less energy.

In other words, we could be in for a rough ride.

4. Economists debate artificial intelligence

How productive will AI make us, really? Leading economist Daron Acemoglu of MIT, a possible future Nobel Prize winner, doesn’t think it will do all that much to rescue us from our productivity slump:

“Using existing estimates on exposure to AI and productivity improvements at the task level, these macroeconomic effects appear nontrivial but modest—no more than a 0.71% increase in total factor productivity over 10 years. The paper then argues that even these estimates could be exaggerated, because early evidence is from easy-to-learn tasks, whereas some of the future effects will come from hard-to-learn tasks, where there are many context-dependent factors affecting decision-making and no objective outcome measures from which to learn successful performance. Consequently, predicted TFP gains over the next 10 years are even more modest and are predicted to be less than 0.55%.”

Contra Acemoglu, GMU’s Tyler Cowen thinks his entire approach “is wrong, and I think it is wrong for reasons of economics”:

“As with international trade, a lot of the benefits of AI will come from getting rid of the least productive firms from within the distribution. This factor is never considered.

And as with international trade, a lot of the benefits of AI will come from ’new goods’. Since the prices of those new goods previously were infinity (do note the degree of substability matters), those gains can be much higher than what we get from incremental productivity improvements.

By the way, the core model of this paper postulates only a single good for the economy.”

And later:

“[W]hat he can’t bring himself to say is that the gains from such new tasks will in fact be small. Because they won’t be. But whether or not you agree, what is going on in the paper is that the gains from AI measure as small because it is assumed AI will not be doing new things. I just don’t see why it is worth doing such an exercise.”

I don’t know how much AI will affect productivity. The estimates out there vary from not much (e.g. Acemoglu) to wildly optimistic. What I do know is that it won’t happen quickly, the gains will be incremental, and it could be many years before we see the effects of AI in the productivity data – if ever.

5. If you missed it, from Aussienomics

We’re number two! – In 2023, the IMF ranked Australia #2 in the G20 for budget management, mostly due to good luck and fortuitous timing. The government’s “responsible approach” claim is overstated and our fiscal position remains vulnerable to economic shocks.

The Kiwi in the coal mine – New Zealand’s economy is in trouble, with a double-dip recession and shrinking per capita growth. The decline stems from a lack of productivity reforms and an excessive focus on equity over efficiency. But Australia isn’t much better, and we could easily join them if policymakers get complacent.

6. BONUS for Paid subscribers – Will China invade Taiwan?

This is perhaps the most important question for Australia right now, given our physical location and that China is our largest trading partner.

So when I saw a new, provocatively-named essay by Richard Hanania titled China Doesn’t Have the Balls to Invade Taiwan, I had to give it a read.

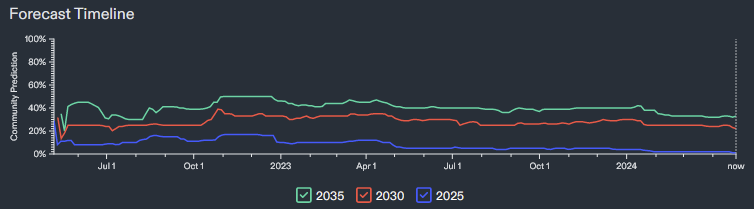

Hanania starts off well, noting that betting markets – which tend to outperform many other forecasts, especially pundits, given bettors have skin in the game – put the odds of “a full-scale invasion of Taiwan” at roughly 33% by 2035.

Xi Jinping will be 81 years old by then, so it’s basically asking if he will invade Taiwan in his lifetime (holding power in China could be tricky, even for artful manipulators such as Xi). Hanania thinks the odds are even lower:

“I would put the number closer to around 10-15% by 2035. The argument goes like this: invading, or even subduing, Taiwan would be extremely risky and hard. China may be a bit of a bully, but it is a risk averse one. There’s no way that they can’t know that trying to conquer Taiwan would pose all kinds of challenges and risks, so they likely won’t do it.”

Xi, of course, believes himself to be the modern incarnation of Mao Zedong. Hanania points out that Mao already tried – and failed – to take Taiwan in 1949:

“The plan started with an invasion of the offshore island of Kinmen, also known as Quemoy, as a steppingstone to reaching Taiwan. The People’s Liberation Army was able to take the town of Guningtou, but their forces were soon surrounded and defeated, with nearly all of the 9,000 Chinese communists [sic] forces who landed on the island eventually being captured or killed. The mainland Chinese would shell Quemoy and the other offshore islands of Matsu during the two Taiwan Strait Crises of 1954-55 and 1958, but never attempt to take either them or Taiwan itself again, realising this was beyond their capabilities.”

Thanks to economic liberalisation, today’s China is much more powerful than it was under Mao. But it would still be a very tricky war, given the treacherous Taiwan Strait, few places where Chinese troops could land, Taipei being surrounded by mountains making it easier to defend, and the fact that Taiwan is armed to the teeth. Add in that the Chinese government has generally shown itself to be risk averse – at least in terms of committing troops to foreign conflicts – and perhaps a still-disastrous blockade, forcing Taiwan into agreeing to “a ‘one country, two systems’ kind of arrangement”, is more likely than an actual invasion.

Invading Taiwan would be hard, but there’s always the possibility – one recently acted on by Putin when he invaded Ukraine – that “China may try to invade Taiwan in the immediate future because doing so will only become harder as time goes on”.

Hanania thinks that Xi’s “rule has been characterised by fear”, which makes him less likely to invade Taiwan than “Putin or Hamas, [who were] thinking in terms of history”.

But with dictators, it’s always hard to tell.

Comments

Comments have been disabled and we're not sure if we'll ever turn them back on. If you have something you would like to contribute, please send Justin an email or hit up social media!