Friday Fodder (17/24)

1. A quantum winner, or loser?

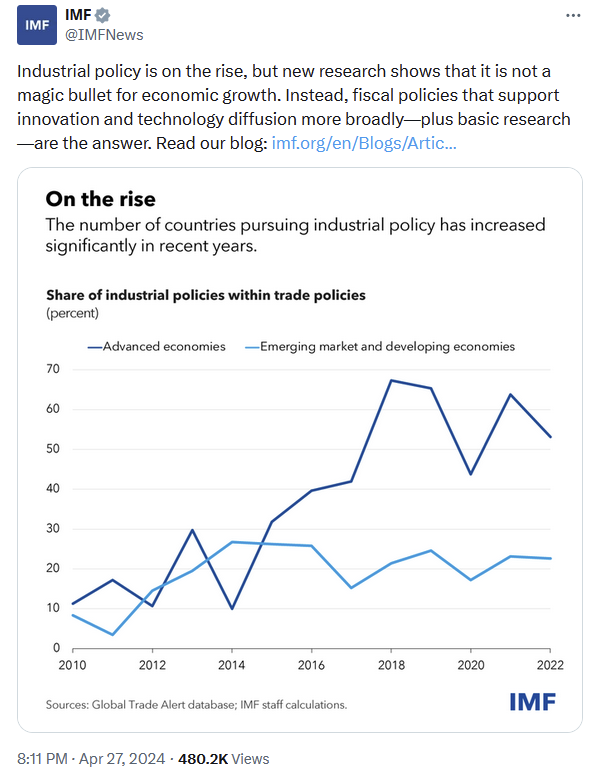

The Albanese government’s “new approach” to industrial policy looks a lot like the “old approach”, in that it seems to be an exercise in picking winners (some of which will inevitably end up being losers). The latest investment under the banner of a Future Made in Australia is a new quantum computing facility in Queensland:

“The Albanese and Miles Governments are harnessing the power and potential of quantum technologies to help deliver a Future Made in Australia and make Brisbane a tech manufacturing powerhouse.

The Australian and Queensland Governments will invest almost $1 billion into frontier technology company PsiQuantum to build the world’s first fault tolerant quantum computer in Brisbane.”

To be clear, there is a chance that this investment works and produces net benefits; there always is. But this particular one smells a lot more like rent seeking than winner picking:

“We do know that the Queensland government has been talking to PsiQuantum and federal government representatives since at least August 2022, according to Queensland ministerial meeting diaries — the kind of basic transparency Labor and the Coalition refuse to accept at the federal level — while Queensland premier Steven Miles met with the companies’ representatives in August last year.

The US company is represented in Canberra by some heavy hitters. Last year Brookline Advisory, made up of veteran Labor staffer and former chief of staff to Richard Marles, Lidija Ivanovski — who was a senior staffer in the Bligh government in Queensland — and former Bill Shorten and NT Labor adviser Gerard Richardson, listed PsiQuantum as clients. Earlier this month, the famous, conservative-aligned C|T Group listed them as well. Local quantum computing firms, take note of what is needed to get access to serious funding in the world of Labor’s ‘Future Made In Australia’.”

As for the prospects of PsiQuantum actually succeeding in building a photonic quantum computer, back in 2021 the FT reported that the venture capital-backed firm claimed they would have it built “by the middle of this decade”.

That has now been pushed back to 2029. I’m no expert, but quantum computing looks to be an extremely speculative technology that may well end up as vaporware, with many in the industry failing to scale their technology from the lab to the real world. But even more of a threat to the outlook is that people are struggling to find a way to make money from it (even hypothetically), because quantum computers can’t “outperform a classical one [computer] on problems big enough to be useful”, limiting their real world utility. Google even has an open $5 million prize available for anyone “that can demonstrate real-world applications for quantum computing”.

As far as speculative investments go, this one is right up there; in fact, that billion dollars to build solar panels in Queensland might even produce greater returns – at least we’ll own the facility, some of which might be salvageable, unlike this quantum computer that will remain in possession of the US-owned PsiQuantum (the government only bought the right to use it).

I really hope we didn’t just buy a billion-dollar paperweight!

2. Tipping, the “scourge of democracy”

The US Fed recently published an interesting research paper on one of my least favourite customs: mandatory tipping. They got stuck into the history and found out that in the US, “tipping went from rare and reviled to an almost uniquely American custom”:

“Whatever the origins of the word, by the late 18th century, it had become increasingly customary in England and other parts of Europe to give tips to servants in domestic and commercial settings. In the early history of the United States, however, tipping remained uncommon and was subject to intense criticism. The practice of giving vails in England was wrapped up in long-standing European class distinctions between the tipper (wealthy aristocrats) and the recipients (servants). Many Americans viewed this practice as antithetical to the country’s founding egalitarian principles.”

Alas, that gradually changed. Just as “tipping began to subside in Europe”, it “took off in America”, for a few possible reasons:

- Freed slaves working service jobs were often paid low wages, making them reliant on tips.

- Cities grew and so did hotels, with many serving food family-style “and some guests would occasionally try to tip for a better cut of meat or more food”.

- Prohibition in the US, which cut off alcohol as a key source of revenue for hotel owners, who started “allowing patrons to leave some extra money for servers… because it reduced pressure on them to increase wages”.

Interestingly, it was not without resistance and some states even banned the practice (albeit briefly):

“Unions in the early 20th century frequently opposed the practice because they felt it stood in the way of workers being paid fair wages and left them too dependent on the whims of customers. Business owners, particularly hotel managers, also feared that the proliferation of tipping requests would annoy and drive away guests.”

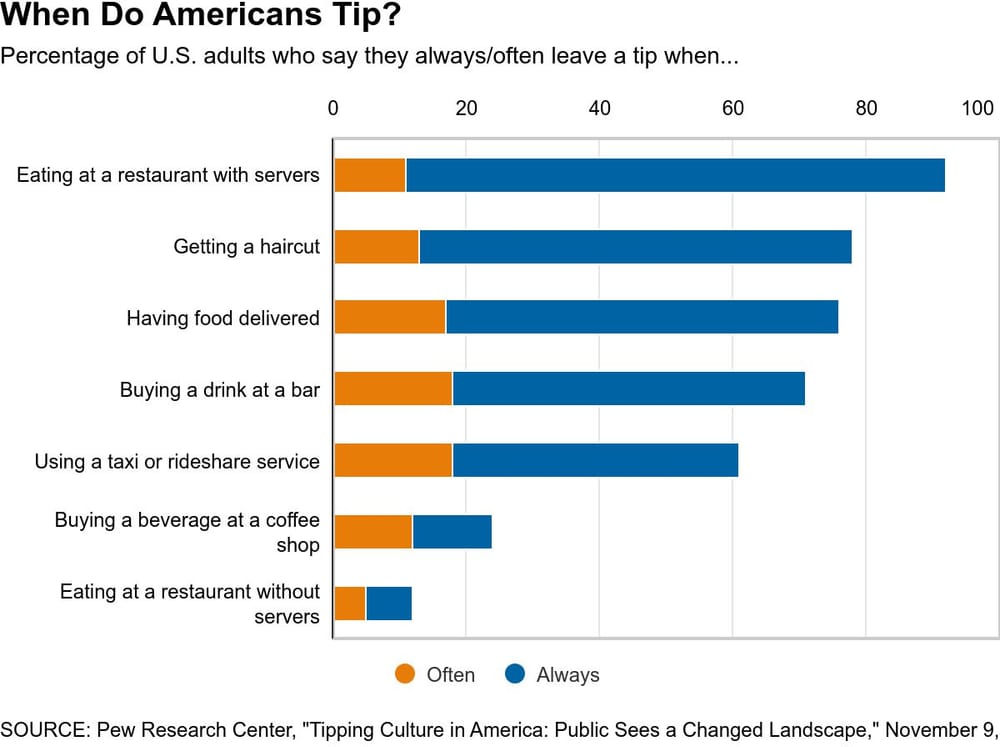

Eventually, tipping won out and now Americans tip for a lot more than just restaurant meals:

But why do the yanks tip? Most say it’s for better service, but the literature finds that “in practice, service quality has little bearing on tipping generosity”.

Unfortunately, the custom is now “so deeply entrenched” that it may be impossible to break, especially because people tend to “focus on menu prices when determining how expensive a restaurant is”, so even if competitors emerged offering a tip-free experience, most people would still “think the restaurant without tipping is more expensive”, driving it out of business.

So for any Aussies planning a future trip to North America, be prepared to tip the standard 20%, which has ballooned from the customary 10% in “the first half of the 20th century” and may not stop there.

3. Should we get rid of non-competes?

Given that we have no new policy ideas in this country, for a change why don’t we copy an idea that might, on balance, actually be a good one? One such idea was just acted on in the US, with the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) banning non-compete clauses. It caused a fair bit of controversy, not so much for the decision but because it’s not clear that the FTC has the authority to make these sort of rulings; in the US, Congress makes the laws.

But non-compete clauses, which exist in Australia, may very well be worth tossing out. According to Treasury citing data from the ABS and 61 Institute, up to 1 in 5 employees have signed a non-compete clause. They provide a few dot points that cover all the potential costs of these clauses, and just a single benefit (can you spot it?):

- Can prevent workers moving to better paid jobs and create staff shortages.

- Can stifle startups and prevent businesses growing and thriving.

- Can support business investment in attracting talent and developing staff.

- May hurt economic growth, if workers stay in less productive roles.

- May limit innovation and the spread of good ideas, making Australian firms less competitive.

- Enforcing these clauses is costly, creating uncertainty for businesses and workers.

Plenty to be fixed there. But before throwing out non-competes and “and other restraints” (Treasury lists five), it’s up to Treasury to do the dirty work of a cost benefit analysis. In this case, they need to weigh up the potential benefits of a ban, such as improvements to allocative efficiency (workers freely moving to more productive firms), against costs such as a reduction in the willingness for firms to train their workers (resolving a version of the hold-up problem).

That won’t be easy, and given that non-competes are so widespread (i.e. plenty of firms and people think they’re worthwhile), the best approach might be to first limit the scope of non-competes (e.g. time limits). Another option would be for the government to phase in a ban for specific cohorts, such as low-wage workers, which was how US states Oregon, Massachusetts, and Washington approached the issue. Or they could exempt certain professions from non-competes, such as those at the frontier of technology, where the benefits of a more mobile workforce are more likely to offset the costs of reduced in-house training.

Whatever the case, I’m glad that Treasury is looking into this. It’s certainly an area that’s ripe for reform.

4. Attempting to buy votes, example #9284

Labour’s Queensland Premier, Steven Miles, is in a bit of a slump. His economic policies are pretty bad, his net approval rating is the lowest-ever for a Queensland Premier, and markets have the Coalition as hot 1.17 favourites to kick him out of office at the election on 26 October.

So, what does one do when confronted such obstacles? A normal person might be tempted to fix their bad policies, take the high ground and argue that the future will be better under their government. But Miles is no normal person; he’s a politician. And as any good politician knows, the best way to win votes is to buy them:

I write a lot about how Australia’s federal government is being fiscally reckless, racking up net debt during an inflationary crisis, making the Reserve Bank of Australia’s (RBA) job more difficult and worsening the cost-of-living crisis. But our state governments might be even worse, and Miles takes the cake for economic mismanagement with this one.

And before you write me, yes, these credits will reduce measured inflation. But as they are debt financed, actual inflation will get worse, unless the RBA completely offsets the impact with tighter monetary policy (unlikely). Whatever Queensland households save on energy they can now spend on something else, which will change the composition of inflation but not its overall rate.

5. If you missed it, from Aussienomics

Inflation’s bumpy landing – Australia’s March quarter inflation figures came in above expectations. Especially worrying was the sticky services and non-tradables inflation, making rate cuts very unlikely this year. To fix inflation we desperately need fiscal policy to start working with monetary policy, rather than against it.

eSafety and the market for ideas – Australia’s eSafety commissioner has been given the impossible task of censoring “harmful” online content - globally. Instead of a censorship tzar of debatable value, a better approach might be to focus resources on promoting critical thinking and demand-side interventions to reduce harmful content.

6. For paid subscribers: the China globalisation paradox

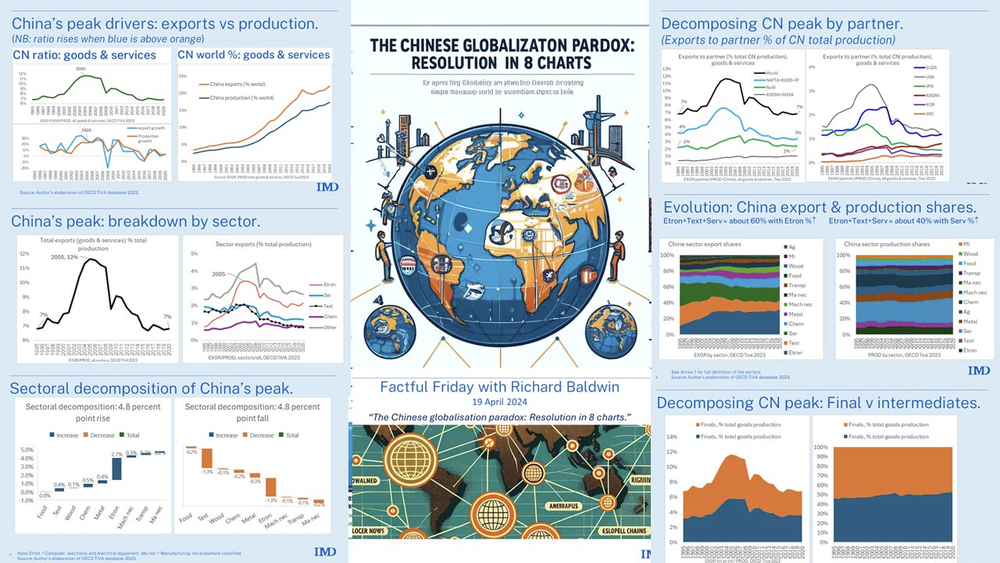

Richard Baldwin, a professor of international economics, shared an interesting series of charts on the “China Globalisation Paradox”, describing the fact that China is deglobalising (“China’s globalisation ratio rose from 7% in 1995 to 12% in 2005 and then fell back to 7% [by 2020]”) at the same time as it’s “shredding through export markets all around the world”:

Baldwin hints at the answer by stating that “since 2005 China has sold an ever-decreasing share of its output to export markets”.

Basically, the supposed paradox is the result of China expanding its productive capacity faster than its trading partners did while also getting wealthier, ensuring more of that production is consumed domestically.

But an aging population and Xi Jinping’s foray into industrial policy, which may slow productivity and therefore real wages growth, could see the paradox reverse (a slowing Chinese economy cannot absorb as much productive capacity). And who knows how well the developed world will be able to absorb China’s exports going forward, given its own turn towards industrial policy and protectionism.

Comments

Comments have been disabled and we're not sure if we'll ever turn them back on. If you have something you would like to contribute, please send Justin an email or hit up social media!