Friday Fodder (2/24)

Here are a few short takes for you to chew over on the weekend, from the week’s happenings that probably didn’t need a full post.

1. Protecting us from ourselves

I was scrolling through the AFR last Sunday, as one does, and noticed the following headline: Labor to overhaul ‘sophisticated investor’ test. Great, I thought – they’re finally going to make it possible for retail investors to buy higher-risk, higher-return products! How wrong I was:

“Labor will make it harder for retail investors to qualify as “sophisticated investors”, as regulators warn access to riskier products such as private equity and unlisted property should be limited to those with more than $4.5 million.

Assistant Treasurer Stephen Jones announced a surprise inquiry into managed investment schemes in October 2022 amid concerns about retirees losing their life savings to strategies they never fully understood.

AFR Weekend understands the government plans to lift the thresholds required to qualify as a “sophisticated investor” from about $2.5 million in net assets, a level that now admits 16 per cent of Australians, though no final decision has been made on the exact level.”

According to the federal government, your net assets alone are what determines your sophistication as an investor. So Paris Hilton can invest in private equity, but a young person with a high tolerance for risk, holding an MBA in financial systems analysis but still saddled with debt from her expensive education, is barred from investing.

Yeah, it’s silly. It’s also how the rich get richer. If the government has a problem with certain products, then it should refuse to certify those products, not set some arbitrary wealth threshold at which point a person, potentially with zero financial literacy, suddenly goes from ‘unsophisticated’ to ‘sophisticated’.

No doubt, certain investment products are risky. But so is parachuting, sunbathing, overeating, drinking, smoking, gambling; yet we allow people to do all of those, regardless of their net worth. At least with investing there’s potential upside!

Personally, I would much prefer Bloomberg’s Matt Levine’s amusing approach to regulating risky products:

- Anyone can invest all they want in a diversified portfolio of approved investments (non-penny-stock public companies, mutual funds and exchange-traded funds with modest fees, insured bank accounts, etc.).

- Anyone can also invest in any other dumb investment; you just have to go to the local office of the SEC and get a Certificate of Dumb Investment. (Anyone who sells dumb non-approved investments without requiring this certificate from buyers goes to prison.)

- To get that certificate, you sign a form. The form is one page with a lot of white space. It says in very large letters: “I want to buy a dumb investment. I understand that the person selling it will almost certainly steal all my money, and that I would almost certainly be better off just buying index funds, but I want to do this dumb thing anyway. I agree that I will never, under any circumstances, complain to anyone when this investment inevitably goes wrong. I understand that violating this agreement is a felony.”

- Then you take the form to an SEC employee, who slaps you hard across the face and says “really???” And if you reply “yes really” then she gives you the certificate.

- Then you bring the certificate to the seller and you can buy whatever dumb thing he is selling.

- If an article ever appears in the Wall Street Journal in which you (or your lawyer) are quoted saying that you were just a simple dentist, didn’t understand what you were buying and were swindled by the seller’s flashy sales pitch, then you go to prison.

2. The return of supersonic travel?

Not since the Concorde (1976-2003), a noisy, expensive aircraft with a questionable safety record, have we had commercial supersonic travel. That might be about to change, if NASA’s latest prototype is anything to go by:

“Nasa revealed the X-59, an experimental aircraft that is expected to fly at 1.4 times the speed of sound – or 925mph (1,488 km/h).

The aircraft, which stands at 99.7ft (30.4 metres) long and 29.5ft wide, has a thin, tapered nose that comprises nearly a third of the aircraft’s full length – a feature designed to disperse shock waves that would typically surround supersonic aircraft and result in sonic booms.

In attempts to further enhance the aircraft’s supersonic capabilities, engineers positioned the cockpit almost halfway down the length and removed the forward-facing windows typically found in other aircraft.”

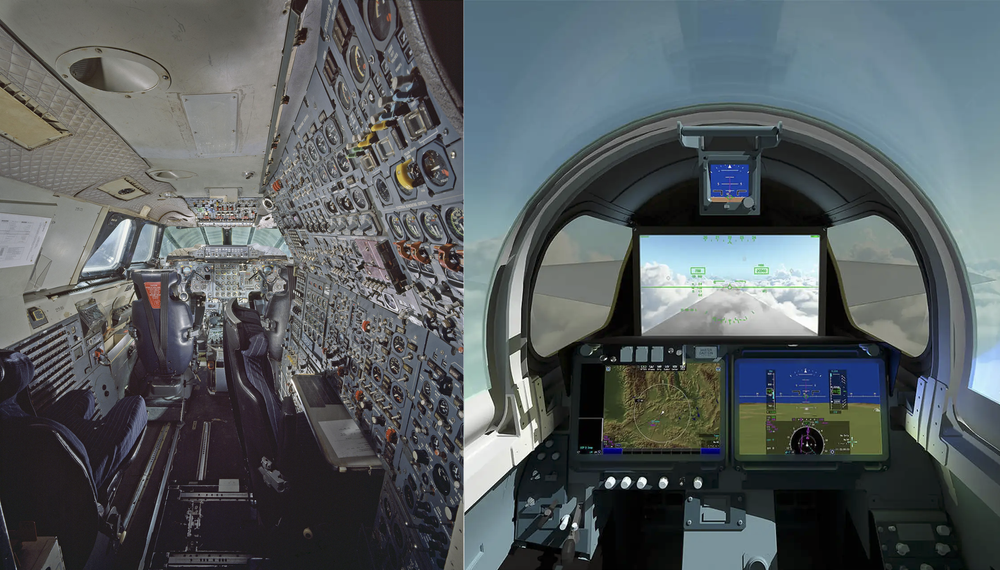

The X-59 is supposed to create a “soft thump instead of a sonic boom” when it reaches supersonic speeds, potentially making it viable for travel over land and one day re-opening the door for supersonic commercial travel. To see how much progress has been made since 2003, here’s a side-by-side look at the cockpits of the Concorde and the X-59:

Despite the X-59’s appearance, it has no windows at all.

Despite the X-59’s appearance, it has no windows at all.

Air travel has been stagnant for decades, with little to no improvement – in fact, travel times have increased over the past 25 years. Could that be about to change? Here’s hoping 🤞

3. Why is there so much fraud in academia?

You may have heard that Harvard’s President, Claudine Gay, resigned earlier this year “after fierce criticism of the University’s response to the Hamas attack on Israel and backlash from her disastrous congressional testimony spiralled into allegations of plagiarism and doubts about her personal academic integrity”.

Gay’s resignation comes hot on the heels of Stanford’s President Marc Tessier-Lavigne, who was ‘outed’ in the middle of last year for having “authored 12 reports that contained falsified information, including lab panels that had been stitched together, panel backgrounds that were digitally altered and blot results taken from other research papers”.

There’s also the ongoing replication crisis in the social sciences, presenting a challenge to the credibility of supposedly empirical, peer-reviewed results in everything from medicine to sociology. More recently, a new paper found that economists have probably been doing the dodgy too, tweaking their regressions to achieve statistical significance:

“A large majority of empirical evidence reported in leading economics journals is potentially misleading. Results reported to be statistically significant are about as likely to be misleading as not (falsely positive) and statistically nonsignificant results are much more likely to be misleading (falsely negative).”

Both Gay and Tessier-Lavigne had long, successful – and lucrative – careers before they were exposed. The same is true for so-called behavioural economists Dan Ariely and Francesca Gino, who are at the centre of an ongoing data fabrication saga. Ariely’s work is so popular that there’s now even a mainstream crime drama called The Irrational based on it.

So I was happy to see the folks over at Freakonomics release a podcast on academic fraud, which is interesting throughout:

VAZIRE: I think one thing we can say for sure is that humans are quite good at self-deception. There’s a lot of reasons why researchers want to believe that they have found the answers to these problems, right? One is a pro-social reason. They want to help solve these problems. They want to help people. Another one is more self-interested, that they want a seat at the policy table. They want attention for themselves. They want to promote their theory and their brand. And it’s also a kind of a survival thing. To stay in academia, to be able to continue to do the research, you need to have successes, and those successes often mean selling your work, and sometimes overselling your work. We want to be taken seriously as scientists and be scientific, and that means being calibrated, and careful, and not exaggerating. But at the same time, the people who do exaggerate are probably going to get more of those successes that get them attention, get them a seat at the table, get them the next grant, the next job, and so on.

DUBNER: When you describe the incentives like that, it sounds to me as if those incentives conspire against the scientific method, do they not?

VAZIRE: Yeah, so if you were just a rational agent acting in the most self-interested way possible, as a researcher in academia, I think you would cheat. I think that is absolutely the way the incentives are set up. I don’t think most people do, but not because of the incentives.

You can listen to the whole episode here.

4. ‘Ai’ming in the right direction

The federal government released a interim report on AI safety in Australia on Wednesday, setting the scene for a light-handed regulatory regime. In my view, that’s the correct approach: consumers are already protected by Australia’s various privacy, copyright and competition laws, all of which capture today’s large language models in some way. Interestingly, the word “risk” was mentioned 133 times in the 25-page report, which is clearly where the focus of any future regulatory regime will be:

“In considering the right regulatory approach, the government’s underlying aim will be to ensure the development and deployment of AI systems in Australia in legitimate, but high-risk settings, is safe and can be relied upon, while ensuring the use of AI in low-risk settings can continue to flourish largely unimpeded. With this in mind, the government’s immediate focus will be on considering whether mandatory safeguards are appropriate. If they are it will consider how to best implement them. This may be through existing laws or new approaches.”

Importantly, the new regulations appear as though they will be less concerned with AI itself – e.g., whether it will one day kill us all, as AI doomers predict – and more with how AI might be misapplied, for example using experimental programs in self-driving vehicles. This is good news, because today’s AI (large language models) are pattern matchers, and there’s no clear path to move from pattern matching to what we might considered sentience.

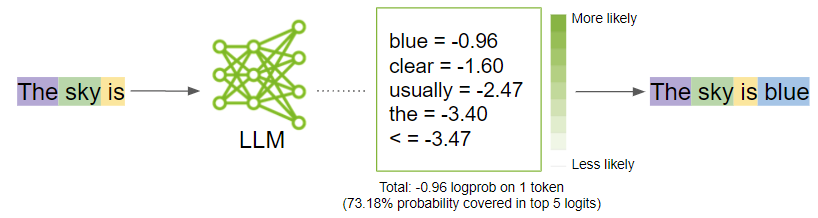

A helpful image showing how basic LLMs work, courtesy of NVIDIA.

A helpful image showing how basic LLMs work, courtesy of NVIDIA.

Large language models have a lot of potential: despite not being ‘intelligent’, there are many applications where having a quick, effective and cheap pattern matcher can save a lot of time. One day they might even be able to drive our cars for us. But there is also a legitimate role for government in ensuring that the appropriate “guardrails” are in place, and that companies have demonstrated “proactive steps to make their products safe to use”, without going so far as to ’lock-in’ the incumbents with overly zealous restrictions on what AI supposedly is and can be.

You can read the full report here.

5. And if you missed it, from Aussienomics

It’s time to break a few eggs: I had a good look at federal Environment Minister Tanya Plibersek’s decision to block Victoria’s proposed Renewable Energy Terminal on the grounds that it might damage the adjacent wetlands and the wading birds that visit there. While it’s true that some damage to the ecosystem would have been inevitable, the affected area was just 0.15% of the total and the birds wouldn’t have been too bothered – they have plenty of alternatives, and their biggest risk is actually the treacherous trip they make over the Yellow Sea twice a year. I concluded that if our governments are serious about transitioning to net zero and building up our renewable energy capabilities, then they really need to start considering trade-offs.

Javier Milei’s shock therapy: I had fun with this one – what can Australia possibly learn from Argentina’s new libertarian economist President, Javier Milei? As it turns out, quite a bit! Milei has tabled a long list of reforms to Argentina’s Congress, many of which would be just as applicable in Australia, especially the need for more competition in the aviation sector (looking at you, Qantas!).

Comments

Comments have been disabled and we're not sure if we'll ever turn them back on. If you have something you would like to contribute, please send Justin an email or hit up social media!