Friday Fodder (24/24)

Just a reminder that there will be no emails next week as I’m going to be in a remote part of Canada with no internet access. I’ll be back on 1 July – Canada Day – with an economic update on… Canada!

With that out of the way, on to this week’s interesting stories.

1. Productivity is everything – so where is it?

Accounting firm Xero recently started publishing some really cool data on how small businesses in Australia, New Zealand and the UK are doing in terms of labour productivity. Unlike the national accounts, Xero’s data are relatively high frequency and provide interesting breakdowns by region and industry, and of course between countries.

Alas, for those hoping for a rebound in real wages, it wasn’t good reading:

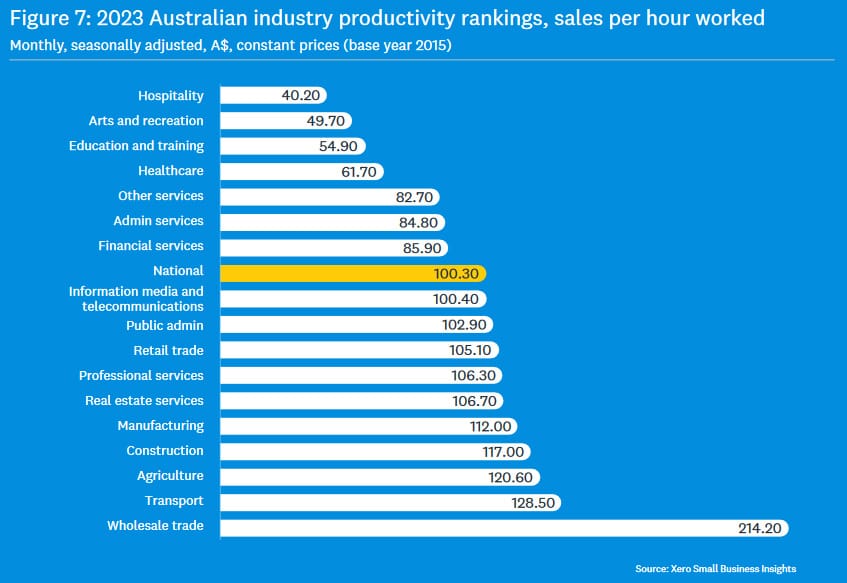

“The most productive industry (wholesale trade) was five times as productive as the least (hospitality) in 2023. Ten industries tracked by the program had productivity per hour worked above the national average. The remaining seven industries, which are below the national average, tended to be service-based industries.”

Services employ nearly 80% of Australian workers. Here’s the chart showing productivity levels by sector:

Xero also provides a breakdown by states, with mining-heavy Western Australia 15% more productive than the country’s laggard, Tasmania. But the higher you are, the further you can fall:

“[A]ll Australian regions tracked also experienced a decline in productivity, compared to 2022. The largest decline was in the most productive region, Western Australia (-4.0%).”

In a services-heavy economy such as Australia, consistent productivity growth is actually quite hard to achieve: we lean heavily on a few very productive industries to lift up the rest of us (noting that the most productive businesses tend to be large and so aren’t covered in Xero’s survey). This is of course a choice; as consumers, we clearly prefer services. But if policy-makers want to see sustainable real wages growth so that we may consume even more services, they need to be careful not to suffocate the golden geese that pay for it.

2. Rates on hold this year

The RBA met earlier this week and left rates on hold again. In its deliberation, the board didn’t even contemplate cutting rates – “the case for a cut was not considered” – but it did discuss a hike:

“Yes, the board did discuss the case for increasing interest rates at this meeting. In the end, it decided that its current strategy of staying the course and trying to bring inflation back down by bringing supply back to demand was the right way to go.”

The RBA was also worried about the recent federal and state budgets, while pledging to look past the temporary impacts they’ll have on measured inflation:

“Recent budget outcomes may also have an impact on demand, although federal and state energy rebates will temporarily reduce headline inflation.”

The NSW government released its Budget on the same day as the RBA’s decision. While more ‘responsible’ than some of the others, the state’s finances were in a much worse position to begin. It also did a very poor job at predicting the GST distribution, which it blamed for turning the $475 million 2024-25 surplus that it forecast in December into a $3.6 billion deficit.

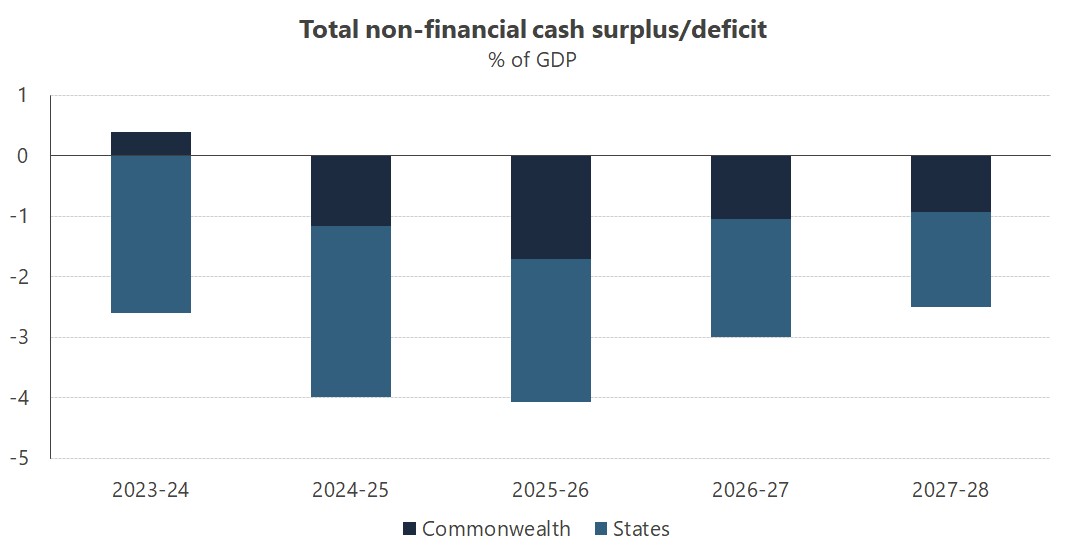

When added to all the other Budgets, it’s clear why the RBA is worried about the impact they’ll have on demand and inflation:

Barring a shock that causes economic activity to fall, for inflation and interest rates to come down, fiscal and monetary policy need to work together,rather than against each other. Clearly our governments haven’t got the memo.

3. India H-1B vs Pakistan

The USA managed to qualify for the T20 World Cup’s knock-out phase, the Super Eight, ahead of former champions Pakistan. Their only loss came against tournament favourites India, and they certainly weren’t embarrassed.

Now, the USA isn’t exactly a proud cricketing nation. Prior to hosting this tournament it had never qualified for a cricket World Cup in any format, and the governing body, USA Cricket, has only existed for five years (the previous iteration was expelled from the International Cricket Council in 2017).

So how did they do it? Immigrants:

“The US cricket team has six players hailing from all around India. One was born in Alabama while his father was going to college here, which makes him a birthright citizen; the others are here on visas. The rest of the team consists of immigrants from former British colonies like Australia and South Africa, and the children of immigrants from the Caribbean.”

I think there are lessons here. The right type of immigration is invaluable; the USA didn’t produce cricket players but it was able to import them on skilled visas, which in the USA are known as H-1B permits. Team USA’s best bowler, Saurabh Netravalkar, is actually a software engineer at Oracle – cricket is his side gig.

Australia has historically done very well out of migration because we’ve targeted people who were likely to succeed in Australia. But the same rate of migration could quite easily have produced much worse effects. I think that distinction’s important whenever discussing migration policy: asking to whom are the visas going is likely more important than how many visas are being issued.

4. Woke AI is boring

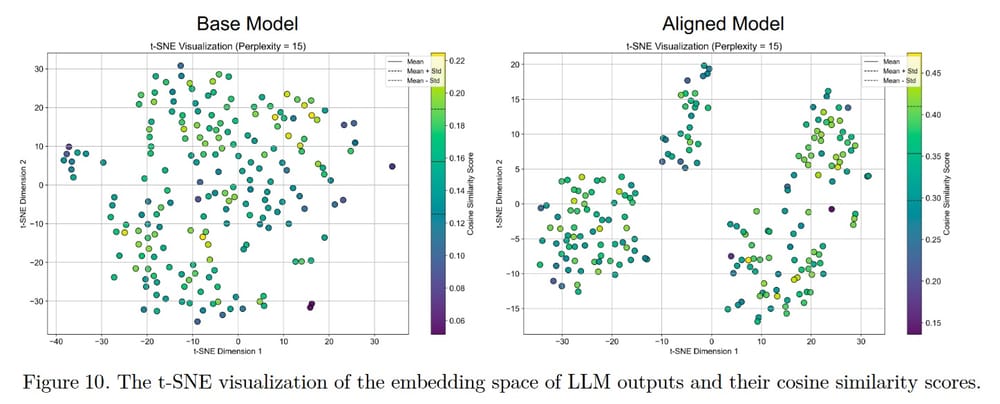

A new working paper on large language models (LLMs) found that “alignment techniques like Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback (RLHF)”, which the creators of AI use to minimise “biases” and “toxic content”, may actually neuter the LLM:

“Our work suggests that this alignment process [RLHF] may inadvertently lead to a reduction in the models’ creativity and output diversity.

…

The potential trade-off between safety and creativity is particularly relevant in the context of marketing, where generating diverse and engaging content is crucial for various applications, such as customer persona generation, ad creation, writing product description, and customer support.”

By ‘aligning’ a LLM, the humans eliminate possible token trajectories even if they’re unrelated to generating toxic or biased content. The LLM then becomes more deterministic instead of generative. When compared to a raw LLM, an ‘aligned’ version forms clusters with empty spaces, “suggesting that the aligned model tends to stick to certain embeddings or generations and expresses the information in a limited number of ways”.

Food for thought when choosing a LLM. If you want creativity (i.e., more hallucinations), choose a NSFW or ‘base’ version. If you want more boring or corporate-esc responses, go with a mainstream model that has had substantial RLHF training.

5. The new consensus

There’s a lot of talk, mostly in the US, about the so-called “new consensus”, aka neopopulism. The current Biden administration has followed it to a tee, led by his “Queen Bee” of economic policy, Jennifer Harris, who “had a hand in everything from making the case for industrial policy to designing a new framework for trade”.

Donald “Tariff Man” Trump is clearly no fan of neloberalism either, meaning it’s effectively dead in the US for at least another four and a bit years:

“This election has no candidates blindly promoting the free market. The last one didn’t either. In the battle of ideas, she [Harris] has already won.”

But was neoliberalism so bad? If you dig past the hyperbole and straw-manning, neoliberalism is just another word for good economics:

“What do I mean by neoliberalism? It means many things to many people—it has become synonymous with die-hard devotion to markets—but it is really just accepting that policies introduce trade-offs, prices convey important information, governments aren’t great at picking winners, and free trade is the closest thing we’ve got to a free lunch. And this has largely been proven true. That does not mean everything is perfect. Opening trade to a country as large as China that has so much cheap labour has caused displacement, and policymakers should have done more for the affected communities. And we learned during the pandemic that we are maybe too dependent on China, though we should not be dependent on any one country, including ourselves. But still, the benefits by far outweigh the costs—we can now appreciate how great things like 40 years of low inflation were.”

That’s from economist Allison Schrager, who cautions that “we have become a victim of our own success and will have to relearn the lessons of the past”.

But it might be even worse than that. The FT’s Janan Ganesh recently took a look at the rise of right-wing populism and whether neoliberalism was responsible. The short answer is a resounding no; many of the least economically liberal countries, such as France, have seen the largest ascendancies of right-wing populism.

In the US, the Biden administration believed – deep in its “gut” – that neoliberalism led to the rise of Trump. By “Building Back Better”, it looked to remove those conditions, which would also “remove over time much of the hard-right threat to the republic”.

But Trump’s rise had nothing to do with neoliberalism:

“‘Gut’, I say, because this notion wouldn’t last a minute in the head. Trump emerged after Obamacare and the bank bailouts: two of the largest federal interventions in private economic life since Lyndon Johnson. His precursor was the Tea Party, whose grievance was too much government, not too little. Framing the market for populism made a sort of superficial sense in 2016. In 2024, it invites ruin.”

Indeed. I will only add that if you don’t like neoliberalism, just wait until you see what replaces it.

5. If you missed it, from Aussienomics

iPhones and AI: What’s next? – Apple has joined the AI race by adding ChatGPT to every iPhone, bringing privacy and security concerns to the forefront; how should governments regulate this rapidly evolving technology without stifling innovation?

Husic is right about the corporate tax – Ed Husic’s call for genuine corporate tax reform could boost investment, raise wages, and drive economic growth. But do we have the political willpower to get it done?

Comments

Comments have been disabled and we're not sure if we'll ever turn them back on. If you have something you would like to contribute, please send Justin an email or hit up social media!