Friday Fodder (25/24)

The talk this week has been dominated by the US and that debate; you know, the one between a corpse and a raving madman, otherwise known as the two candidates running to be President of the world’s largest economy and strongest military, Joe Biden (81) and Donald Trump (78).

The US November election has obvious implications for Australia given our close trading and security relationship, so let’s jump right in and take a look at what unfolded.

1. Should a corpse be President?

Ignoring Trump for a moment, the debate put to rest the rumours that Biden’s mental faculties have faded. They clearly have; insiders close to him report that he’s lucid only between 10am and 4pm. The first debate began at 9pm, a time of night when he “is more likely to have verbal miscues and become fatigued”. You don’t get sharper with age, so it’s conceivable that in a year or two Biden’s ‘window’ will be even smaller, or completely non-existent.

That’s a problem for the person holding the nuclear codes!

But even if Biden is mentally compromised, is he still better than the alternative? Some, such as Snowden Todd, think even if Biden’s brain was completely zombified, the answer is a resounding yes:

“The case for electing a living corpse is simple: most of America’s biggest risks right now are international. Domestically, the country is quite stable. The economy is strong, and while debt is ballooning at an unsustainable rate, the issue will not come to a head for some time. Even if a fiscal crisis were imminent, Trump and Biden are both essentially Peronists, so neither changes the fiscal equation enough to matter anyway.

…

But internationally, geopolitical tensions have peaked. And who is in the White House will affect how other countries navigate the next four years. Trump presents distinct risks because he has the quality of being difficult to read and is seemingly out for blood after a feckless first term. No one—not China, North Korea, Iran, or Russia—knows what a second Trump term would look like in terms of foreign policy, only that he would go beyond his first term in his efforts to reinvent America’s position in the world. No more John Bolton.”

There are two sides to the “madman” theory. The side Todd is alluding to is that Trump is so crazy that he’ll do something really stupid, if given the opportunity.

It’s certainly plausible that a second Trump term would trigger fresh geopolitical conflicts. For example, Trump has already expressed a desire to replace income taxes with tariffs, despite it being a mathematical impossibility. How might China respond to losing a large part of a half trillion-dollar export market? Invade Taiwan? What would Trump do then?

The other side of the “madman” theory is that Trump is so crazy that no other leader would dare provoke him:

“Madman theory assumes that making seemingly unbelievable threats – such as embarking on nuclear war – are more credible if they are coming from someone who is unpredictable and possibly unstable. This idea flies in the face of traditional neo-realist theories of international relations that assume that people are rational and consider the consequences of their decisions. This explains the logic of nuclear deterrence, when there is mutually assured destruction – meaning that logical decision makers would never go as far as using their nuclear arsenal.

Instead, madmen supposedly don’t consider the consequences of their actions – which should, in theory, instil fear in their enemies.”

If you take that view, then another Trump Presidency would be better for international affairs. And there’s some credibility to that idea: after all, the Middle East and Ukraine blew up on Biden’s watch, although history shows that “madmen” haven’t fared all that well in the long-run.

So, Trump or Biden? On balance, having a madman in charge may be the riskier option – especially given that the Supreme Court just ruled that “the president is now a king above the law” – than a man with limited mental faculties outside of a 6-hour window, who can be ‘managed’ by his aides ( or wife).

As for their economics, Todd is right that they’re both essentially Peronists who think they can spend their way to prosperity and will ratchet up failed policies such as protectionism and import substitution (dressed up as ‘strategic’ industrial policy or national defence). While Trump is obsessed with “winning” trade by balancing an accounting artefact and has “various stupid and destructive economic policies”, Biden has proposed “completely insane tax regimes that would cripple our economic dynamism and growth if enacted”.

None of that will be good for a small, open and relatively free trading country like Australia. But a corpse might still be marginally better than a madman.

2. Please stop lying to people

The Biden/Trump debate again brought the issue of lying to the forefront. Economist Arnold Kling recently lamented the “crisis” of lying in American politics. For example:

“How many Republicans in Congress really think that Mr. Trump is capable of handling the Presidency? I would bet that at least some of them would tell you in private that he makes them worried and uncomfortable.”

As for the Democrats:

“Mr. Biden is unfit for office today. Yet no leading Democrat is calling on him to resign. And if he insists on staying on the ticket, it is likely that the Democrats will rally around him. And they will rally around his Vice President as well, even though in their hearts they cannot believe that she is the right choice for the country.”

In a similar vein, blogger Scott Alexander noted that a lot of harm can be caused by “a few white lies”, such as a hypothetical Biden aide thinking they can hide their leader’s diminished mental capacity by telling people he’s always lucid, rather than mostly lucid:

“I support the Principle of Charity. Nobody ever thinks in their own head ‘Haha, I am an evil person who is deceiving my friends and the world’. They think ‘I’m telling little white lies that don’t matter, for the greater good’. But the flip side of that is that every horrible giant deception was perpetrated by people saying ‘I’m telling little white lies that don’t matter, for the greater good’. And so if you are ever tempted to tell what seem like little white lies that don’t matter for the greater good, you should consider the possibility that actually, you’re being about as mendacious as anybody ever gets, and you have a decent chance of causing a disaster. And if you do cause a disaster, the fact that you didn’t go into it smirking ‘muahaha, now I shall be an evil person and cause a disaster’ won’t be exculpatory.”

I like to think that in Australia, as uniquely flawed as our political system may be, our respective parties would have turfed both candidates long ago. Our voters tend to force political retirements well before anyone becomes an octogenarian; our oldest elected Prime Minister was John McEwen at 67 years of age, and we’ve only had one septuagenarian ever elected to the House: Edward Braddon, aged 71, way back in 1901.

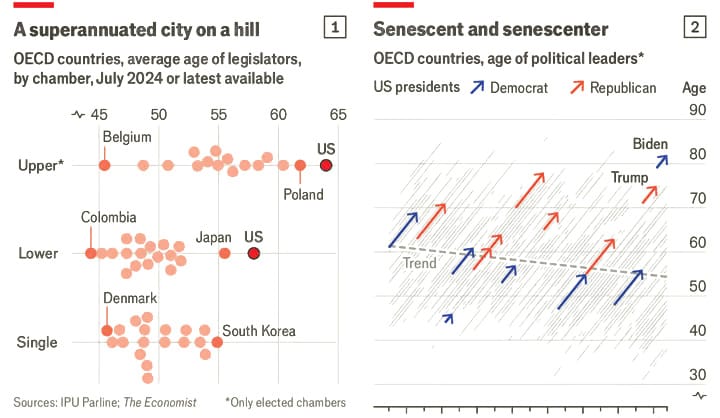

But the US has dozens of them in Congress, with their legislators uniquely old by global standards and getting older, despite the OECD trend towards youth.

Both parties unite around their respective candidates seemingly no matter what, even if they have to lie to do so (seriously, it takes a lot for a party to turn on one of their own). Kling warns that such lies have consequences:

“What worries Dreher and me is not just that the elites have become accustomed to lying, but that the public is becoming accustomed to being lied to. Right there is the case for making the analogy with the late Soviet regime.

I believe that this country desperately needs an end to the mass lying. For politicians and journalists, there has to be much higher correlation between what they say in public and what they believe to be true. As long as we are being fed lies so assiduously, I will be inclined to say that we are in a crisis.”

For a take from the left, Matt Yglesias recently made similar points from the perspective of economic reform, specifically how lies about fossil fuel subsidies undermine the proponents’ policy goals:

“You can dupe people into a one-off, like the invasion of Iraq, but to have a sustained program of policy reform, you need to do things that work. And the political system is too large — hundreds of legislators, thousands of staffers, innumerable bureaucrats and interest groups, along with media, influencers, and other stakeholders — to operate on a conspiratorial basis.

…

The climate version of this is, if anything, worse. Convincing people that there are trillions in fossil fuel subsidies makes the case for regulatory action, new investments in green energy, or really any kind of climate action look weaker, not stronger. By characterising ‘failure to enact a carbon tax’ as a form of subsidy, you’re confusing loosely attentive people who care about climate change, making politicians look more gutless than they are and existing policy look dumber than it is, and suggesting that there’s an easy solution at hand when there isn’t.”

We’re certainly not immune from such lies in Australia. Regular readers might recall a certain former rugby player and independent Senator who loves to tell us all about Australia’s fossil fuel subsidies, with assertions like “we spend more money on fossil fuel subsidies than we do on public schools”.

But as I wrote earlier this year, “the large fossil fuel subsidies he hates are mostly due to estimates of untaxed externalities – pollution, environmental damage, climate change – and even household electricity bill relief (for which Pocock voted)”.

Pocock is telling white lies. And by doing so, writes Yglesias, he’s “about a million times more likely to confuse people who are friendly to your cause than to actually persuade anyone worth persuading”.

To remove Pocock’s “subsidies” requires a carbon tax. Sure, that would be better than probing in the dark with industrial policies such as a Future Made in Australia. But it doesn’t matter because we’ll never get one if politicians like Pocock are going around trying to trick people into thinking we can just end fossil fuel subsidies that don’t exist, rather than telling the truth and making the case for what is a politically challenging tax.

3. The diminishing returns to AI

Or should I say, the diminishing returns to scaling up large language models (LLMs). Bill Gates recently gave an interesting, and – in my opinion – accurate reply to the question of how much further LLMs can scale:

“The big frontier is not so much scaling. We have probably two more turns on the crank of scaling… the most interesting dimension is what I call metacognition where understanding how to think about a problem in a broad sense and step back and say OK, how important is this answer, how could I check my answer, what external tools would help me with this. The overall cognitive strategy is so trivial today that it’s just generating through constant computation each sequence, and it’s mindblowing that works at all. It does not step back like a human and think OK I’m going to write this paper and here’s what I want to cover… and so you see this limitation.”

The “big frontier” is getting from LLMs to human-like reasoning. But doing so will require a “general breakthrough on metacognition”, which could be years away – if it ever arrives.

In the meantime, we can expect to enjoy a bit more scaling (GPT-5?) and fine-tuning as AI providers scrape the world’s remaining audio, video and image data. But don’t expect A( G)I any time soon, or for LLMs to revolutionise the world, given their limitations. Not without another technological breakthrough, anyway.

And if there’s no breakthrough, then according to Sequoia Capital, revenue-generating capability becomes more urgent for AI companies:

“Consider how much value you get from Netflix for $15.49/month or Spotify for $11.99. Long term, AI companies will need to deliver significant value for consumers to continue opening their wallets.”

Can today’s LLMs offer that kind of persistent value to consumers? For most AI firms, the answer is probably no. They’ll keep working, to be sure, but without a tech breakthrough then just a couple more “turns on the crank of scaling” may not be enough to really crack the consumer market. If so, then “it will cause harm primarily to investors” (because today’s valuations will prove to be unrealistically optimistic).

4. Unintended consequences #537,890

Australia recently passed a bill that “introduced world-leading minimum standards for gig workers”, so that “gig workers would ultimately take home more pay”.

At the time, Employment Minister Tony Burke said:

“If there’s a tiny bit extra you pay when your pizza arrives and they’re more likely to be safe on the roads, then I reckon it’s a pretty small price to pay.”

Perhaps. But what if the changes mean the pizza is never ordered, and the gig worker pays with their job? Evidence from New York City and Seattle, where in 2023 the likes of Uber were ordered to pay gig workers more, suggests that’s likely to be a consequence of such legislation:

“Because its costs were up, Uber implemented two supply side changes. It said that it could save money by grouping drivers into delivery slots. Gig workers, appreciating their flexibility, expressed dismay with the new rules. Then also, Uber cut 25% of its delivery work force.

…

Meanwhile, on the demand side, consumers complained about an app fee that Uber added. Already paying an app service fee and a tip, diners said the extra charge was excessive.

…

Uber Eats said that orders shrunk by 45% in Seattle after adding its $4.99 fee.

So, although workers were paid more, fewer orders meant they took home less.”

The laws and supply and demand can be rough. Higher wages for gig workers will attract more drivers. But higher prices for their services will reduce their chances of finding a rider or a delivery to make. Gig workers will spend less time driving and more time idling (or driving around with an empty vehicle), pushing their take-home wage back down towards the market wage.

Perhaps that’s a better outcome for gig workers; I don’t know. But it’s certainly worse for consumers, and is definitely more inefficient (goodbye, productivity). And if it means more hours spent on the road, then it could actually worsen road safety outcomes for gig workers, even if it lowers the per hour odds of an accident.

5. Fahrenheit 451 down under

If you weren’t aware, Australia has a social media censorship tsar, and the Albanese government looks set – with full support of the Coalition – to impose age limits and other restrictions on it in the name of “safety”, despite the dubious evidence.

We don’t have free speech in this country but that doesn’t mean it’s not still dangerous when both sides of politics are actively trying to suppress it even further. As Sanford’s Jay Bhattacharya warned, it’s as though “they read Fahrenheit 451 and somehow think the firemen were the good guys?”

Your friendly reminder that it’s not possible to age-verify minors without also checking adults. And unlike in-person checks, digital verification involves uploading your documents to the social media provider, a third-party verifier, or the government itself.

I’m sure the Russians can’t wait to get their hands on it!

6. And if you missed it, from Aussienomics

What’s up with Canada? – Despite its proximity to the US and abundant natural resources, Canada’s economy is hampered by inter-provincial trade barriers, powerful domestic cartels, and declining productivity, leaving it vulnerable to global trade tensions.

Why the RBA should hold steady – It’s probably too late in the cycle to hike rates any further when what’s desperately needed is tax, spending and regulatory reform.

Comments

Comments have been disabled and we're not sure if we'll ever turn them back on. If you have something you would like to contribute, please send Justin an email or hit up social media!