Friday Fodder (26/24)

I’m currently riddled with some variant of the latest coronavirus strain, FLiRT, so apologies if there are any glaring mistakes in the below. But the world doesn’t stop spinning just because I’m sick, so here are some interesting developments from the week just gone:

1. A future made in Australia the trough

I’ve been quite critical of the government’s $22.7 billion Future Made in Australia scheme, which I think will end up wasting a good portion of its initial capital. I believe that for two main reasons:

- The knowledge problem. Politicians and their experts don’t know which projects will pay off; they don’t have the knowledge needed to make accurate assessments of winners and losers.

- The incentive problem. Even if they did have that knowledge, “good” industrial policy is likely impossible in a democracy because political goals, such as ensuring jobs are located in key electorates and subsidies are directed towards donors, will see many funds allocated to “losers”.

Today’s politicians will pay no personal price for any Future Made in Australia failures – to the contrary, they’re more likely to be rewarded with ribbon-cutting ceremonies, donations, and votes – so don’t have much of an interest in ensuring these investments maximise social welfare. One reason for that is because the benefits are concentrated on local residents and producers, while the costs are diffused across the entire country. That results in waste: projects with high costs but low benefits can “pass”, because it makes sense for producers to lobby for subsidies even if the total cost to society is considerably greater than their personal gain.

Mancur Olson’s The Rise and Decline of Nations warned that the cumulative and accelerating nature of such lobbying – if not countered – will, over time, result in slower economic growth and declining well-being. Ten million here, a billion there, throw in some protectionism and before you know it you have a sclerotic, low-growth economy.

According to a recent investigation by the SMH, a Future Made in Australia has already turbocharged that process:

“Lobbyists including former Gillard government official Eamonn Fitzpatrick, former Rudd government adviser Claire March and former Queensland state Labor adviser Evan Moorhead are among those working with companies involved in the Australian-made policy, particularly in mining and manufacturing.

With Labor vowing to spend billions of dollars on the Future Made in Australia industry plan, lobbying firms have helped clients secure $840 million for a lithium refinery, $35 million for a cobalt and nickel mine and $50 million for a cement manufacturer.

The deals add to questions about the Labor-aligned lobbying firm that helped Silicon Valley company PsiQuantum gain $940 million from the federal and Queensland governments for a quantum computer facility.”

A Future Made in Australia will be a boon for lobbyists and well-connected producers in favoured sectors. But the future of Australia will be worse off because of it.

2. Social media age limits are based on junk science

Albo and Dutton both want to impose age limits on social media. I’m not sure what their specific motives are – Dutton has probably never met a problem he thinks he can’t solve by banning it, while Albo thinks it’s having “a negative impact on young people”. They also have the support of News Corp, which has been running a campaign all year called Let Them Be Kids, which appears to be full of emotional anecdotes but lacking any real critical analysis.

I’ve looked into the science behind these claims a couple of times, which flows from a book by Jonathan Haidt full of serious methodological errors and “is not supported by science”. The actual science basically shows that the causal effect of social media on kids’ mental health is statistically no different than zero. But that hasn’t stopped our leaders trying to go all authoritarian on us, presumably because it’s popular with voters; as John Stuart Mill observed back in 1828:

“I think I have observed that not the man who hopes when others despair, but the man who despairs when others hope is admired by a large clan of persons as a sage.”

Fear sells. But just in case you wanted even more evidence that social media isn’t the poison its critics claim it is, Peter Gray recently penned an excellent essay lamenting the lack of critical analysis from the likes of Albo and Dutton:

“Too many people are taking this book as an authoritative summary of the research regarding effects of smartphones and social media and concluding that we must take these tools away from children and even early teens. As a society we have almost a knee-jerk reaction to believe that the solution to any problem experienced by kids is to deprive them of yet one more freedom, and this book is helping to jerk some of those knees even further.”

Gray worries that by banning social media for young people, we will “deprive kids of opportunities”, when what we should be doing is working to develop norms around social media and smartphone use, teaching kids how to use them responsibly. Scapegoating social media also distracts us from addressing the actual causes of deteriorating mental health amongst teens.

3. We’re number 20!

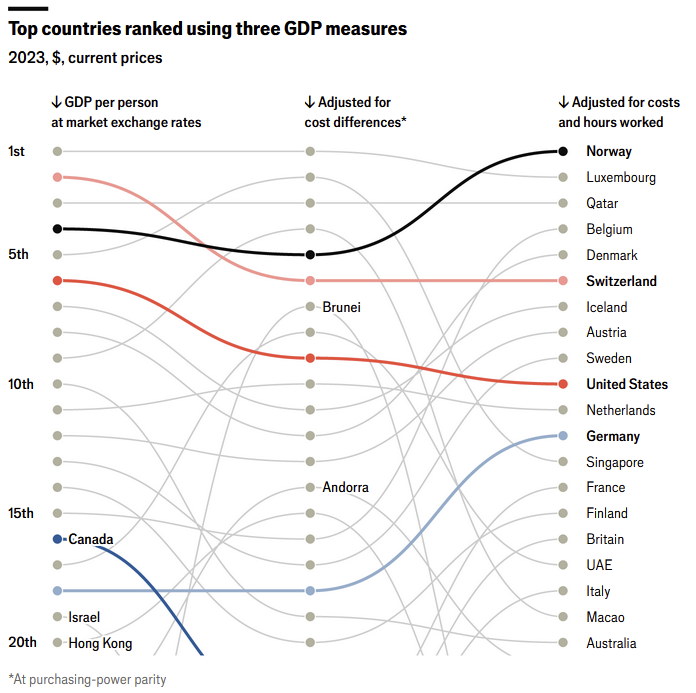

The Economist has a neat graphic showing wealth by country after adjusting for exchange rates, local cost differences and hours worked. Perhaps reflecting our mining-heavy economy and that we work relatively more hours than other countries, after these adjustments we go from the 10th wealthiest to 20th:

Not great but at least we’re ahead of Canada, which is ranked 24th just barely above Türkiye (I recently wrote about their woes here). If you want to check out the data in all its glory, The Economist was kind enough to open source it.

4. (In)Efficiency in Japan

Japan has a dynamic economy that houses several tech powerhouses and is a world leader in certain technological frontiers, such as robotics. But it’s also extremely static, with over-staffed firms obsessed with procedure and paper forms, and until 28 June, required to use floppy disks:

“Although Kono only announced plans to eradicate floppy disks from the government two years ago, it has been 20 years since floppy disks were in their prime and 53 years since they debuted. It was only in January 2024 that the Japanese government stopped requiring physical media, like floppy disks and CD-ROMs, for 1,900 types of submissions to the government, such as business filings and submission forms for citizens.”

Beware passing legislation without a sunset clause! The cumulative effect of regulations left unchecked for decades, each innocuous by themselves, will drain the dynamism out of any sector.

5. Zoning reform isn’t enough

According to a new working paper from Yale researchers, the rise of land-use zoning correlates with more expensive housing:

“There is almost no relationship between real housing price growth and the restrictiveness of zoning in the 1890-1929 period (coefficient of -.02). Zoning was adopted by almost every city in our sample during the 1920s. We see a slightly steeper gradient over the next two periods (coefficients of .48 and .29, respectively). In these periods it is possible both that the existing zoning regimes were causing higher price growth and that home price appreciation was incentivising cities to adopt even more restrictive measures, particularly by the 1970s. The gradient in the final period (1980-2006) is even steeper, however (coefficient of .67), suggesting a closer relationship between zoning and home price appreciation towards the end of the 20th century.”

But zoning isn’t everything! Regulations on top of regulations create unintended consequences, such as excessively large elevators in the US (and Canada!) that raise the cost of installing one by as much as three times compared to high-income peer countries in Europe and Asia:

“New elevators outside the U.S. are typically sized to accommodate a person in a large wheelchair plus somebody standing behind it. American elevators have ballooned to about twice that size, driven by a drip-drip-drip of regulations, each motivated by a slightly different concern — first accessibility, then accommodation for ambulance stretchers, then even bigger stretchers.

The United States and Canada have also marooned themselves on a regulatory island for elevator parts and designs.”

I went and read the paper on which the NYT article is based and it had information on Australia. It turns out that in terms of adding to costs we’re worse than Europe but not quite as bad the North Americans, at least for buildings below a certain height:

“Australia’s building code takes a hybrid approach to elevator cabin sizes,

with European-style requirements up to about five stories, and then a

more American approach above that height.”

One can imagine the myriad other seemingly small and innocuous regulations that, put together, work to raise construction costs, especially for the most affordable homes: apartments. No wonder we’re no chance of meeting the government’s housing targets.

6. The most distorted result in history

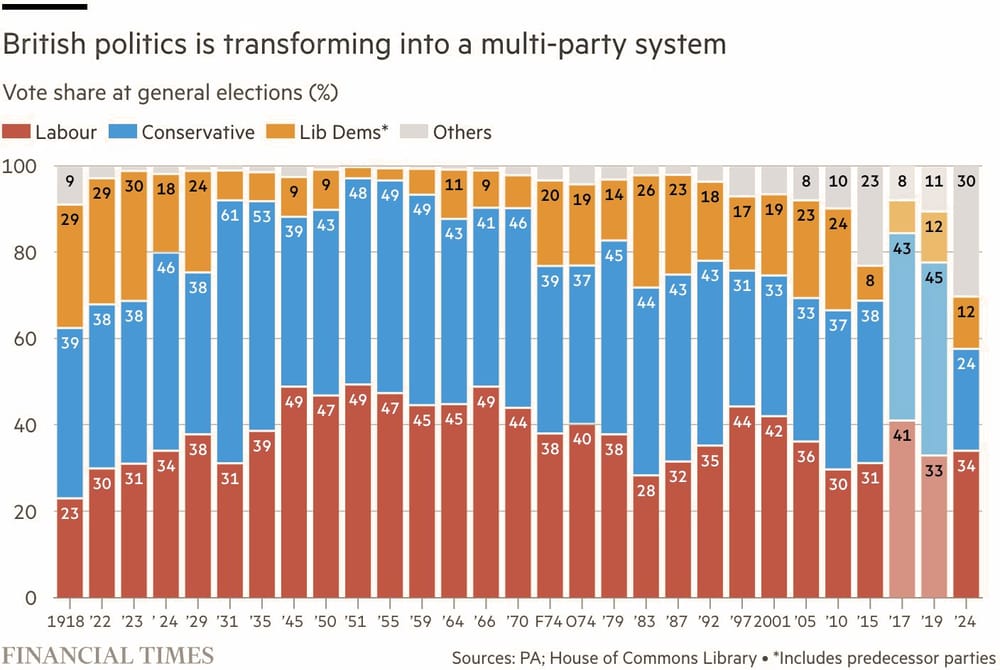

Ok, I’ve somehow managed not to talk about it until now but the UK election really was something to behold. Described as “the most distorted result in history”, the Labour party actually won 64% of the nation’s seats with just 34% of the vote, a mere 1 percentage point more than they received at the 2019 election (and only because of Scotland):

How was the possible? The UK has a ‘first past the post’ electoral system with multiple parties garnishing over 10% of the overall vote. Under such a system, you can win a majority with a relatively low share of votes.

The FT’s John Ben-Murdoch worries that such a system “can’t cope” with a multi-party system, while historian Anton Howes argues that it’s the system working at “its best, allowing the electorate to mete out proper punishment and let another team have a proper go of it without having to bend to fringe parties that hardly anybody at all wants” (John later agreed with that assessment).

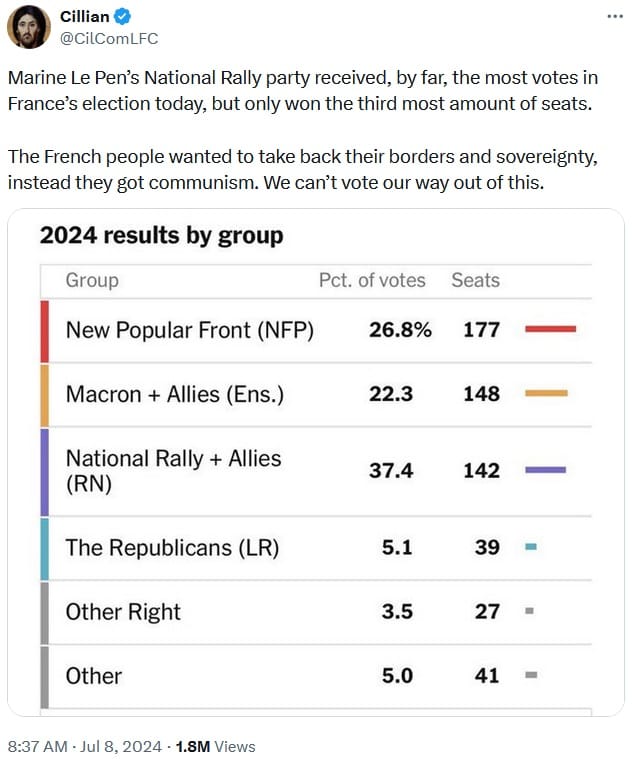

Meanwhile, in France:

Fascinating.

7. If you missed it, from Aussienomics

Vienna’s secret housing sauce – While Vienna’s social housing model is often praised as a solution to housing affordability issues, its applicability to Australia is questionable due to differences in our institutions, as well as potential drawbacks in the Viennese system itself.

Should we be more like Denmark? – There’s a lot to like about Denmark’s approach to mortgages, but transplanting it to Australia may not be optimal given our existing regulatory framework and housing policies.

Comments

Comments have been disabled and we're not sure if we'll ever turn them back on. If you have something you would like to contribute, please send Justin an email or hit up social media!