Friday Fodder (30/24)

Lots to cover this week starting with a misjudged attempt by NSW Premier Chris Minns to revoke working from home privileges for many of the state’s public sector employees. Also in today’s Fodder:

- QLD’s Premier Steven Miles is throwing cash around like it’s confetti

- Google probably isn’t a monopolist

- How Adam Smith helps nations escape poverty

- Contra industrial policy, we should welcome cheap goods

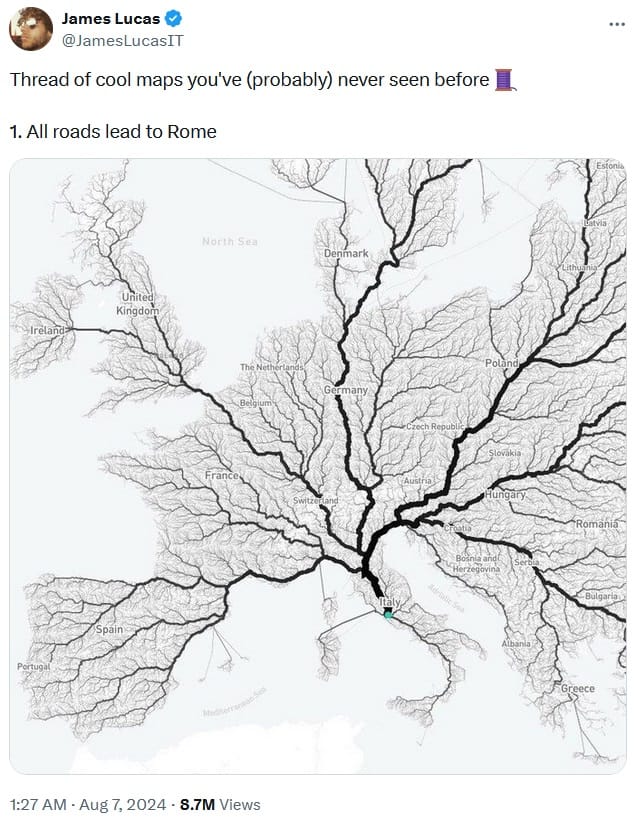

- The Romans built a lot of roads

(Not) working from home

This week the NSW Premier Chris Minns declared that full-time work from home was over for the state’s public sector employees, effective from next week:

“While the circular did not specify minimum attendance requirements, Mr Minns said full-time employees would be expected to work at least three days in the office.

He said overseas studies showed people were less productive when working from home.

‘There is a drop in mentorship. There is less of a sense of joint mission,’ Mr Minns said.

‘This is about building up a culture in the public service’.”

I’m not sure what evidence Minns is citing; he has a habit of playing fast and loose with the facts, and from what I understand the general consensus is that while fully remote workers may be slightly less productive, that can be offset if management lifts its game:

“The numbers paint a picture of small, positive productivity gains for hybrid work. The savings in commuting time more than offset the losses in connectivity from fewer office days. In contrast, the impact of fully remote working on productivity is typically mildly negative. Fully remote workers can struggle with mentoring, innovation and culture building. However, it appears this can be reversed with good management. Running remote teams is hard but done well can deliver strong performance.”

And therein lies the real issue, right? Banning full-time work from home is easier than implementing organisational change, lifting management up so that even fully-remote workers can be more productive than if they came to the office. By taking the lazy option, Minns is potentially saddling taxpayers with extra costs, because having remote workers:

- reduces office and wage costs;

- improves recruitment and lowers retention costs, and staff attendance (fewer sick days);

- cuts congestion and pollution through less commuting; and

- supports those with care and disability challenges.

Of course, there are other factors: internal knowledge transfer is reduced without in-person contact, and from the state’s point of view spending in the inner city will be lower than otherwise (although this is offset by higher spending elsewhere). So for most workers and their employers, being in the office for at least a couple of days a week is probably closer to optimal than fully remote.

Still, this strikes me as a poor decision by Minns. If the more talented bureaucrats in the state aren’t compensated for their loss, whether financially or with other benefits, then I’m sure some will start eyeing up the exits. He also didn’t communicate it all that well, with senior bureaucrats – including his uncle – seemingly rebelling against the decision just a day after it was announced.

What I don’t understand is why Minns didn’t just quietly pass the rule for new hires (including people moving within the public sector)? Over time, that would essentially achieve the same outcome. Is the NSW coffee shop and commercial real estate lobby really that strong that it had to be done abruptly and unilaterally?

Throwing cash around like confetti

Oh boy. Right as the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) was warning the government that “recent public spending announcements by federal and state and territory governments” were making its job more difficult, Queensland Premier Steven Miles announced that, if re-elected, his government “will establish 12 publicly owned fuel stations”, at an initial cost of around $100 million with no cost recovery.

According to Miles, these stations “will charge a fair price for fuel, increase competition, and ensure Queenslanders have more choice when it comes to filling up”. Presumably Miles knows what a “fair price” for fuel is. If it’s well below the market price, people will have to queue for it, essentially paying with their time rather than dollars. Taxpayers will have to make up for any operational losses.

But Miles wasn’t done there. He also wants to trial price controls by banning private petrol stations from raising prices by more than 5 cents a litre a day. Given the weekly price cycles, that’s likely to raise average prices, effectively punishing those who fill up on the cheap days. If there were large upward movements in wholesale prices – e.g. if Russia invaded someone again – servos might just stop selling petrol altogether. Oil is not the same as a banana: it can be stored for a long time.

It also wasn’t clear if the limit would be indexed to inflation; if not, over time the cap would shrink until petrol stations were effectively unable to meaningfully raise prices at all, gradually reducing competition as stations failed and potentially even creating shortages. Of course, if Miles was still in charge, presumably he would then just nationalisation the entire sector – problem solved!

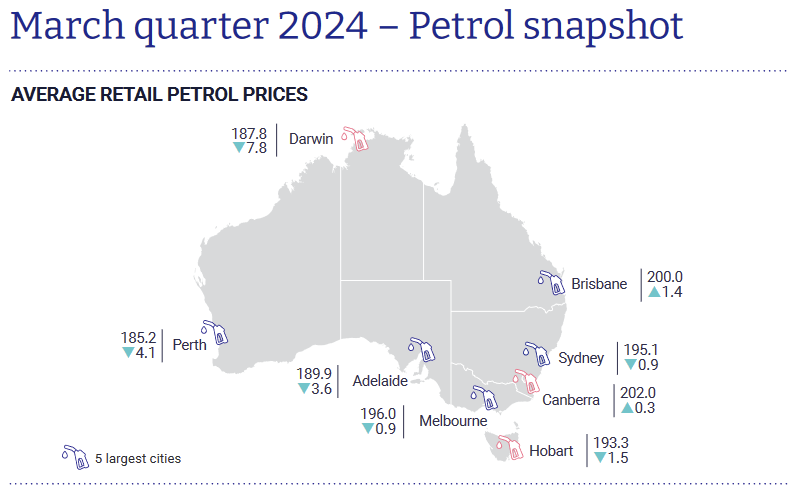

Look, it’s true that the petrol situation in Brisbane is less than ideal. Prices are higher than in just about every other capital city:

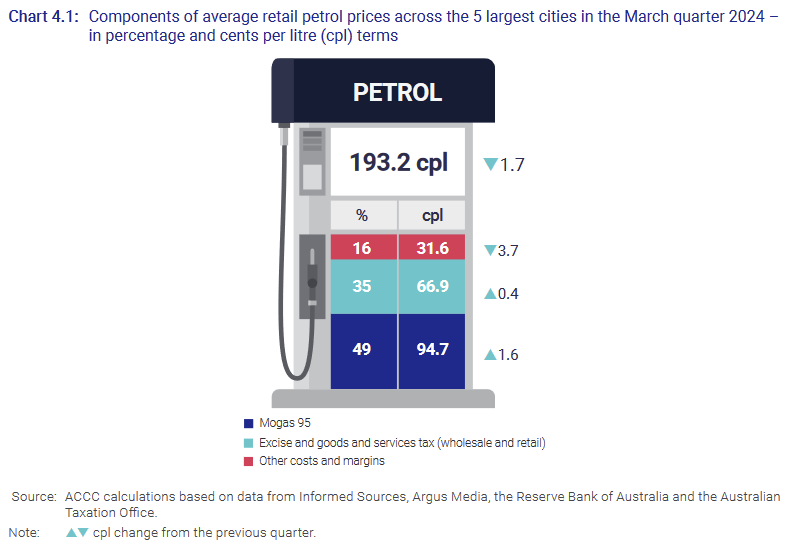

The reason prices are higher in Brisbane is because there’s less competition: there aren’t as many stations per capita and there are fewer independent stations than in other cities. As a result, service station margins are higher in Brisbane than in other cities, although context is important – margins are still the smallest component of retail fuel costs:

The ACCC gave the Queensland government some suggestions on how to fix it back in 2017, such as increasing price transparency and competition. For example, the government could provide “commentary and analysis about retail petrol prices by location and by brand/retailer over time”.

The ACCC also noted that the number of service stations in Brisbane had not increased in a decade, despite population growth, suggesting that there might be other reasons why the market isn’t functioning properly. After all, the profit motive is strong – why aren’t new entrants showing up and bidding down margins? Is something stopping them? Zoning laws? I don’t know, but it’s worth looking into before doing something truly insane like setting up public service stations!

Is Google a monopolist?

According to a judge in the US District of Columbia, yes:

“After having carefully considered and weighed the witness testimony and evidence, the court reaches the following conclusion: Google is a monopolist, and it has acted as one to maintain its monopoly.”

This is an area where lawyers and economists often disagree. Well, most economists. Former ACCC chair Rod Sims had this to say:

“It’s a terrific outcome. Google is effectively a monopoly in search including in Australia. Monopolists get complacent, and consumers therefore lose out. There are all sorts of innovations we may not be getting. The other point to make is Google was paying Apple at least $US12 billion per annum to be the default search engine. If you’re so sure of your product, and you think you’re going to win out anyway, why would you pay $US12 billion? It’s just extraordinary.”

It’s a shame that there are still economists out there who don’t understand competition, especially when they end up in competition bureaus. Competition is a process, not an outcome. These economists can do a lot of damage when they wield the fist of government, depriving us consumers of things we like – or perhaps worse, imposing costs like the stupid “do you accept cookies” boxes on every European website.

For an actual economist’s take on this decision, here’s International Center for Law & Economics’s chief economist Brian Albrecht back in 2020 when this case was first levied on Google:

“There’s fair reason to believe that these exclusive contracts intensify competition, as Ben Klein and Kevin Murphy argue here. Again, it is important to see this as part of a more general system of competitive contracting, not just pricing. Apple could also sign contracts with Microsoft to default to Bing.

…

Now I do not mean to imply that no actions can ever be anti-competitive. Price fixing does occur. As I argued before, the real problem is that the monopoly/innovators like Google and Apple aren’t able to extract enough of the surplus they generate through a simple price.

But paying money to other firms and restraining each other’s behaviour are completely natural parts of a competitive process. Google is simply offering better terms to Apple and customers than Microsoft can. That’s how competition works!”

Albrecht also covered the decision itself – it’s a few hundred pages long – in some detail on X, which appears full of contradictions and misunderstandings, such as assuming that Google’s scale is a barrier to entry (it’s not), stating that there’s no search innovation then citing Microsoft’s recent innovations, and claiming that the “general search market has remained static for at least the last 15 years”.

Really?! No change since 2009? Perhaps these judges need to get out and actually use a search engine once in a while, rather than having their underpaid and overworked associates do all the legwork for them.

How nations escaped poverty

German historian and sociologist Rainer Zitelmann recently published a book about how nations escaped poverty (that’s the title) and hit the podcast circuit. I haven’t read it yet but it looks to be a good one based on his interview with Human Progress’ Chelsea Follett. For example, on foreign aid:

“There’s a lot of people in Europe and the United States, they think redistribution is the way. So it means that the rich countries, America, United States, Europe, should give a lot of money, development aid to poor countries, Africa, for example. But you know, they tried it for 50, 60 years, and it didn’t work. I quote a lot of scientific studies in my book, that the effect was in the best way zero. But in a lot of cases, it made things worse. It only helped corrupt elites, the money went in their pockets and not to the poor people who really need it. And so development aid did not work. I think we have to admit it. And there are so many scientific studies that prove it.”

On China:

“I have a friend at Beijing University, Weiying Zhang, and he always repeats, our success in China was not because of the state, but in spite of the state. It was because of Deng Xiaoping’s economic reforms.”

The most recent success stories are Poland and Vietnam, and the way they escaped poverty is with some good ol’ Adam Smith:

“Economic freedom is the most important thing for the fight against poverty. And maybe to add this, some people think, Adam Smith is like, or someone like Gordon Gekko that we know from the movie Wall Street, like greed is good and someone who’s in favour of rich people. But this is not true. It’s very hard to find positive sentences about rich people in Adam Smith’s both books. It’s even easier to find it in the writings of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels than with Adam Smith. But you find a lot of remarks that his main concern was poverty. His topic was how can we fight against poverty.”

You can listen to the full interview here.

We should welcome cheap goods

JD Vance, Donald Trump’s running mate in November’s US election, copped a lot of flack recently for claiming that “a million cheap, knockoff toasters aren’t worth the price of a single American manufacturing job”.

But as the ANU’s East Asia Forum (EAF) editor’s pointed out, if a cheap toaster costs $10, that’s $10 million per job. I think you’d be hard pressed to find anyone – even the most rusted-on supporter of industrial policy – to agree with that claim.

But what it has done is bring to the fore one of the most important concepts in economics: opportunity costs. Trade-offs are everywhere, and in this simple case spending $10 million on a manufacturing job is clearly not worth the opportunity cost of a million toasters (or working on other more valuable things in America). Unfortunately, today’s industrial policy advocates appear to be forgetting that lesson:

“Trump’s vision might perhaps be called an Annie Oakley industrial policy: anything you can manufacture, I can manufacture better. There seems to be little underlying logic that guides the selection of individual policy measures.”

But the Biden government’s industrial policy isn’t much better. Instead of welcoming the environmental and consumer welfare benefits of affordable, imported goods, it has pumped its own industry full of subsidies with the goal of dominating “low-emissions goods and technology”, a costly strategy also used by China.

But to stop China just doing it bigger and better, it has drawn “on the mantra of ‘overcapacity’” – a term with “no meaning in international trade law” – to try and “jawbone Beijing into acting to stop Chinese clean energy manufacturers ‘flooding the market with cheap goods’, echoing J.D. Vance’s pining for made-in-the-USA toasters”.

As retaliation ramps up, Australia stands to benefit by importing “cheap Chinese solar panels that otherwise might have been sold to Europe or the United States”. That is, assuming a Future Made in Australia doesn’t get in the way:

“Some commentators have been comforted by Treasury publishing a national interest framework to guide the Future Made in Australia policy and avoid costly mistakes.

But the reality is the framework has already been broken by the government multiple times.

Treasury debunked Albanese’s push to create solar panel and battery manufacturing industries in Australia, strongly indicating the billions of dollars of subsidies would not make Australia globally competitive in these areas because many countries were well ahead in the race.

Yet, the government has committed $1 billion to boost local solar manufacturing through a ‘solar sunshot’ program and more than $500 million for battery manufacturing.”

It starts with industrial policy: making toasters, or in this case solar panels and batteries, in Australia. But when that inevitably fails, or the ongoing subsidies become prohibitively expensive for taxpayers, it ends in protectionism. The losers are you, me, and the environment.

Fun fact

The Roman Empire built something like 400,000km of roads, 120,000km of which were paved. That’s enough paved road to lap Australia around eight times.

Comments

Comments have been disabled and we're not sure if we'll ever turn them back on. If you have something you would like to contribute, please send Justin an email or hit up social media!