Friday Fodder (31/24)

Another week, another round-up of things I thought were interesting, starting with some more on a Future Made in Australia.

An infant that never grows up

On Wednesday, Anthony Albanese stood up in Parliament and compared his vision for a Future Made in Australia to the politicians who helped established a car industry in Australia:

“If you look back to the creation of the car manufacturing industry under John Curtin and Ben Chifley and their vision for national reconstruction after the second world war, there is an economic multiplier effect.

…

That’s making sure that you look forward and plan for it and invest in it. Because the truth is that there is an economic multiplier effect with all of this. It’s always more than the sum of the parts.”

Albo’s right that there are multipliers: for every dollar spent, a certain amount of economic activity is generated. But he’s being a pretty crappy economist by ignoring the other side of the ledger: that such “visions” have to be taxed in the first place, which isn’t costless, and that there are alternative uses of those scarce resources that may have much larger multiplier effects.

So, I really, really hope that creating the equivalent of another auto industry is not his measure of success for a Future Made in Australia. The legacy of Australia’s auto industry is, in the words of former Productivity Commission Chair Gary Banks, “an infant that just would not grow up”. It created benefits for firms and their employees, sure, but it cost consumers an awful lot more in terms of reduced choice, lower quality, higher prices, and greater taxes.

An oreful winter

According to Chinese steel-maker Baowu’s chairman Hu Wangming (Baowu produces ~7% of the world’s steel), the current conditions in China’s steel sector are like a “harsh winter… longer, colder and more difficult to endure than we expected”, likening it to the previous lulls in 2008 and 2015.

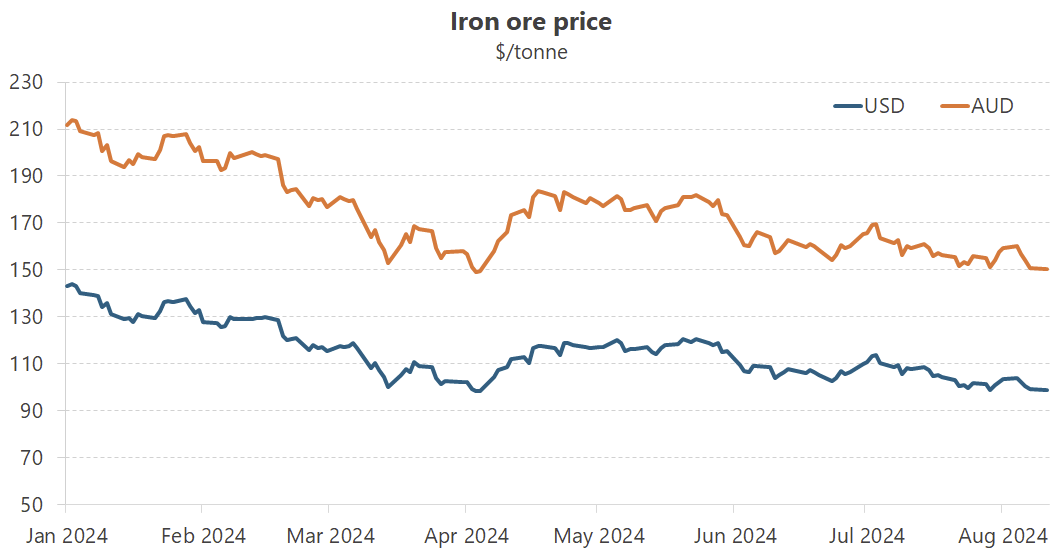

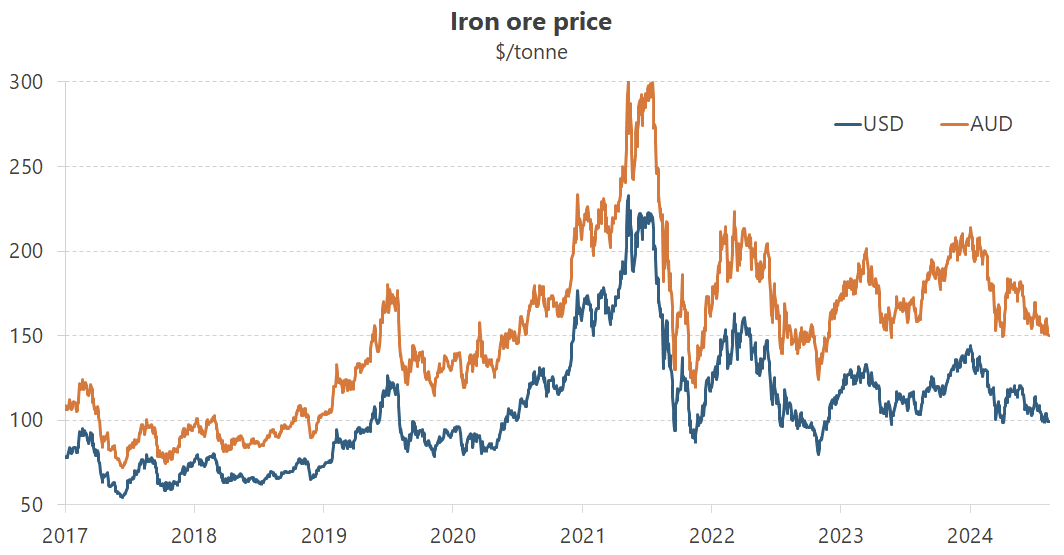

He has a point; steel prices and output are down and the benchmark price of iron ore, the key steel-making ingredient, is down 30% this calendar year.

That’s from a great height, though: iron ore’s previous lows in the “winter” of 2015 were just below $US40 – or around $US50 in today’s dollars. The exchange rate was similar (~70c versus 66c today), so prices can certainly fall quite a bit further before seriously pressuring the major Aussie miners. Conditions were worse than this in 2015, 2016, 2017, 2018, 2019, and 2020.

The 90th percentile of iron ore producers operate at a cash cost of US$86/tonne and are likely to drop out first if prices go much lower. But that’s not too far above some Aussie players, either – Mineral Resources has a mine with costs at $67–77/tonne – and because it’s lower quality ore you need to add ~20% to that, putting them under pressure if prices fall much further.

Testing times, for sure, although not quite an iron ore winter just yet – it can get colder! But even an iron ore autumn isn’t great news for the mining companies and their stock prices, as when iron ore prices fall they’re essentially losing pure margin. And it’s certainly bad for the federal and Western Australian governments, who might see the windfall revenue ‘surprises’ they’ve grown so accustomed to over the past few years very quickly become revenue shortfalls.

So, it’s a bloody good thing that they used their recent Budgets to cut spending and pay off debt, taking the heat out of inflation and giving us the fiscal capacity to continue paying our bills if iron ore revenues dry up. Oh wait, that never happened – they both increased spending (the Feds by 4.5% in real terms!), raised net debt projections, and left us much more vulnerable to a future iron ore winter. Great…

The Raygun of inflation?

The Kiwis became the latest advanced economy to cut interest rates:

“New Zealand’s annual consumer price inflation is returning to within the Monetary Policy Committee’s 1 to 3 percent target band. Surveyed inflation expectations, firms’ pricing behaviour, headline inflation, and a variety of core inflation measures are moving consistent with low and stable inflation.

The Committee agreed to ease the level of monetary policy restraint by reducing the OCR to 5.25 percent. The pace of further easing will depend on the Committee’s confidence that pricing behaviour remains consistent with a low inflation environment, and that inflation expectations are anchored around the 2 percent target.”

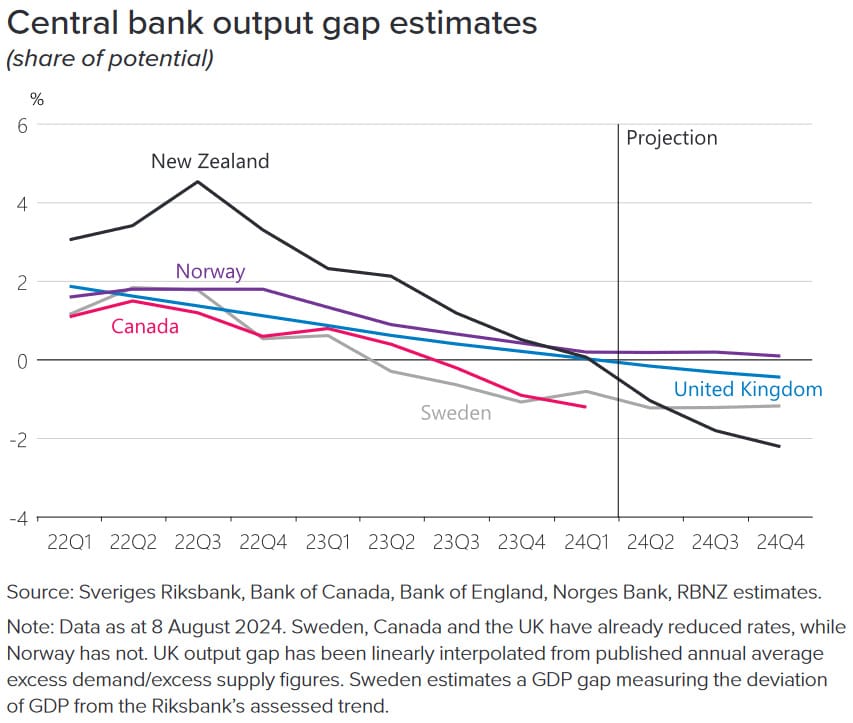

Inflation seems to be back to within target just about everywhere, except Australia. And the Kiwis managed it despite overcooking their economy badly during the pandemic; their central bank provided this chart showing just how juiced it was. Inflation was inevitable:

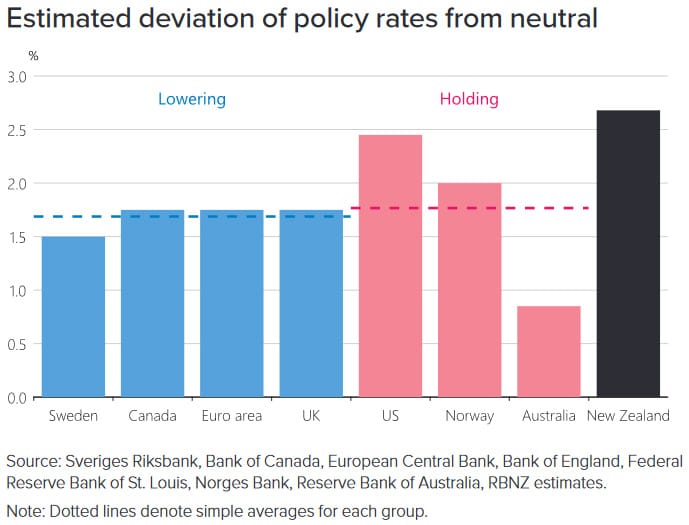

The Kiwis started raising rates in October 2021. Clearly too late, but not as late as Philip “no rate hike until 2024” Lowe and the RBA were; they didn’t start tightening until May 2022! And it looks like the Kiwis think we’ve still got it wrong, holding rates barely above the estimate of neutrality (i.e. the point where supply and demand are equal and therefore non-inflationary) and well below the peer-group average.

Yikes. With the US Fed set to start cutting next month after a better than expected inflation reading on Wednesday night, is Australia now the… Raygun of inflation?

Australia’s employment recession

The July labour force report came out yesterday and showed that Australia added a whopping 58,200 jobs in the month – since this time last year, 455,400 more people are gainfully employed.

However, 23,900 additional people were also unemployed in July compared to June because the participation rate increased to a record high. Prime-aged population growth, cost-of-living pressures, structural change – whatever the reason, more people were looking for work. As a result, the unemployment rate ticked up to 4.2%.

More new people employed than unemployed; great. But it’s when you get into the weeds that the foundations of our labour market start to look shaky. The detailed data aren’t out yet, but just looking at the June quarter’s breakdown by market and non-market and it’s not pretty:

- In the past year, total hours worked are unchanged.

- Market hours worked, excluding agriculture, forestry and fishing, have fallen for three consecutive quarters and are down 1.0% from a year ago.

- Non-market hours worked are up 1.7% over the past year.

Looking from prior to the pandemic (December 2019), market hours worked are up 7.0% – pretty much in-line with cumulative population growth over that period – while the non-market sector has increased its hours worked by 18.7%.

Basically, the strength in Australia’s labour market is coming entirely from government spending, with the market-based parts of our economy flashing recession alarms. I’m sure it’ll be fine.

Could you be an Olympian?

The Paris Olympics is over and people are inevitably looking to 2028 to see if they can get a taxpayer-funded ticket to Los Angeles. Just how hard could it be, anyway? It depends on the sport:

“[The Ringer has] put together a misery index of Summer Olympic sports for the everyperson. There are three tiers in this ranking: Actually, Like, Really Fun (Can We Try This at Home?), Your-Ego-Will-Never-Recover Levels of Shame, and You Could Literally … Die? And in the interest of your sanity and ours, we’re looking at each category of sports in the Olympics (e.g., swimming or track and field) and not each individual event (e.g., the 200-meter freestyle or sprint).”

Their best and worst sports are both ones in which Aussies excelled in Paris – surfing (“would definitely kill a regular person”) and slalom canoeing (“really fun”).

Personally, with breaking not in Los Angeles it has to be shooting: Turkey sent a 51-year-old with no lenses, eye cover or ear protection and he walked away with a silver medal. How hard could it be?

The consequences of China’s economic crisis

There’s a saying that you should never back a wild animal into a corner. I think there’s an under-appreciated risk of industrial policy such as a Future Made in Australia that it will do exactly that to China – back it into a corner.

How? Well, when our politicians eventually realise that, actually, making shit in Australia is really hard because we have to bid labour and capital away from more productive sectors to do so, our politicians might resort to outright protection on top of subsidies. They did it with car manufacturers for several decades – why not solar, hydrogen and lithium hydroxide, too?

But doing so moves many of the world’s largest economies – including China – towards something more closely resembling the Russian model. After being burned by sanctions and the oil price collapse in 2008, Russia shifted its economic model towards import substitution. As a result, it’s now poorer but extremely self-sufficient, allowing it to “take more risks without fear of reprisal”.

China is in the middle of an economic crisis of its own making. And the West is making it easier for Xi Jinping to push towards the Russian model:

“US policymakers also need to recognise that China’s overcapacity problem is exacerbated by Beijing’s pursuit of self-sufficiency. This effort, which has been given major emphasis in recent years, reflects Xi’s insecurity and his desire to reduce China’s strategic vulnerabilities amid growing economic and geopolitical tensions with the United States and the West. In fact, Xi’s attempts to mobilise his country’s people and resources to build a technological and financial wall around China carry significant consequences of their own. A China that is increasingly cut off from Western markets will have less to lose in a potential confrontation with the West—and, therefore, less motivation to de-escalate. As long as China is tightly bound to the United States and Europe through the trade of high-value goods that are not easily substitutable, the West will be far more effective in deterring the country from taking destabilising actions. China and the United States are strategic competitors, not enemies; nonetheless, when it comes to US-Chinese trade relations, there is wisdom in the old saying ‘Keep your friends close and your enemies closer’.”

Do we really want to take part in the process of making China more self-sufficient and potentially reckless on the global stage, while at the same time becoming an easy target for its propaganda machine? I wouldn’t think so. Yet that’s exactly where a Future made in Australia nudges us.

Fun Fact

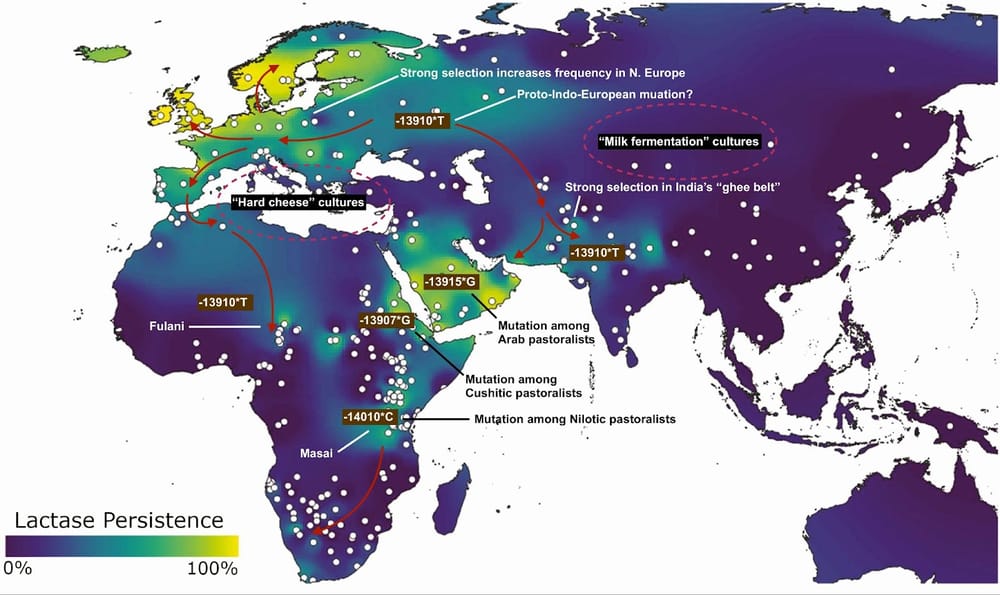

Only 30% of adults can digest milk, and almost all of them descent from Europe – over 90% of those with Northern European ancestry can process it. Here’s a cool map, courtesy of Razib Khan:

According to Khan, being able to drink milk into adulthood is “unique” to humans:

“Because continued functioning of the enzyme lactase allows the ability to process milk sugar to persist into adulthood, in the scientific literature lactose tolerance is today referred to as lactase persistence. Most humans stop producing lactase after the age of five. Normally indigestible, lactase breaks lactose into galactose and glucose, both of which the body can readily absorb. This same is true of all mammals; the stage when offspring can no longer digest milk sugar correlates strongly with the age of weaning, freeing the mother up to reproduce again.”

How did it happen? Near the end of the Bronze Age, a bunch of people – likely Celtic – migrated to southern Britain (England and Wales). They happened to have a gene conferring lactase persistence, i.e. the ability to digest milk without uncomfortable side effects. With the prevalence of farming in the region it gave them a ’natural genetic advantage’, and by the time of the Iron Age around half of all Britons had the gene, compared to just 7% of mainland Europeans.

Comments

Comments have been disabled and we're not sure if we'll ever turn them back on. If you have something you would like to contribute, please send Justin an email or hit up social media!