Friday Fodder (32/24)

Plenty of interesting things to cover this week, starting with a follow-up of sorts to Monday’s post on price gouging.

Price gouging is virtuous

Before you bite my head off, hear me out. I think the anti-price gouging crusade gets a lot of support because the English dictionary does the economic case for it a big disservice. For example, here’s what Google gives me:

Gouge: overcharge or swindle (someone); or obtain money by swindling or extortion.

That does sounds awful, doesn’t it? But the way “price gouging” is used by politicians and the media usually describes something different – simple supply and demand. Without price gouging, crises and the associated shortages and rationing would persist for far longer:

“Price gouging is wonderful for all the reasons that letting supply equals demand is wonderful. When there is a limited supply, then a sharply higher price directs that supply to those who really need it. It’s day 2 after the hurricane. Who really needs gas? An ambulance, police, or fire truck? A handicapped person, needing to get to a doctor across town? Or someone who could bike, take public transit, or walk with just a little effort to go see a friend?”

That’s from economist John Cochrane, who believes “we should praise price-gouging”, because it:

“[D]irects scarce supply to the people who really need it, encourages new supply to come in, encourages holding stockpiles for a rainy day, encourages efficient use of stockpiles we have sitting around, and encourages people to substitute for less scarce goods when they can”.

Now, is it fair that some people may legitimately not be able to afford these goods, even if they badly need them, during a time of crisis? Absolutely not. But banning price gouging doesn’t solve that moral quandary. As Cochrane notes, “don’t distort prices in order to transfer income”.

If you must, hand out cash and let people spend it on whatever they want so that everyone doesn’t immediately go and simply bid up the price of the scarce product. Willingness to pay, rather than ability to pay, then determines how supply is allocated. But messing with prices by banning “price gouging” just makes everything worse:

“Hoarding goes with price controls, anticipated empty shelves. Why did people buy tons of toilet paper in the pandemic? They were worried about not being able to get it in the future. If the stores had not been worried about price-gouging, they would have raised the prices a lot more, and people with that idea would have gotten the message, don’t bother to stock up now — and if you really need it, there will always be some in the store later.

Laws limiting price gouging also reduce supply. If gas goes to $10 per gallon, there is a huge incentive for anyone to has a gas truck to fire it up, buy some gas out in the sticks, bring it in and sell it to local gas stations. If you can’t sell it for a good price, and the gas station can’t recoup that price, it doesn’t happen.”

Given that the US has a Presidential candidate who is appears to be blissfully ignorant of economics, and another who knows barely enough to be confidently dangerous, I’m not terribly confident that price controls died with Nixon.

The right kind of protectionism?

Ok, there’s no right kind of protectionism because trade is mutually beneficial so any policy that lessens it is welfare-reducing. But if the political winds have shifted and the median voter is demanding you do something, then I guess the European Union’s approach is probably as good as you’ll get:

“The European Commission on Tuesday cut its proposed tariff on imports of Tesla cars built in China, as it broadly maintained other planned punitive duties it set in July on Chinese-made electric vehicles.

…

An executive from the EU said on Tuesday it still believed Chinese EV production had benefited from extensive subsidies and proposed final duties of up to 36.3%.”

It’s hard to say how much the Chinese government (taxpayer) has subsidised EV production, so I imagine there’s quite a bit of guesswork being done here. But at least there’s some attempt to quantify the “advantage” China’s government has given its auto makers.

However, where it falls apart is that it shouldn’t matter; any Chinese renminbi forcibly reallocated into an EV that’s going to be exported is a loss for China and a win for Europe. These tariffs effectively tax away that gift, so that European residents will pay ~19-46% more for Chinese EVs.

If it doesn’t kill off the trade entirely, then it’s basically a tax hike. But at least the damage is contained.

…Or is it? The problem I see is that the European Union isn’t exactly some innocent party here. It also heavily subsidises its EV sector, offering “an array of benefits for EV producers and consumers, including tax breaks for manufacturers, thousands of euros of subsidies per car for buyers and tax credits for households and businesses that install EV chargers”.

So, China will probably retaliate by whacking tariffs on something else, like European internal combustion vehicles or dairy products. More new taxes, fewer gains from trade, lost efficiency – the usual anti-growth rules apply. Everyone is worse off when governments engage in tit-for-tat trade disputes.

But it could have been a lot worse. The European Union could have raised import taxes so high as to effectively embargo all Chinese EV imports, as the US did, or used punitive import quotas instead – at least tariffs can be measured and the damage limited by some objective ‘assessment’ of Chinese subsidies.

So, not the worst case of protectionism out there. The European Union will get a bit of revenue from the new import taxes, and unlike US citizens its residents will still have the option to buy Chinese EVs, albeit at higher prices.

Culture beats policy

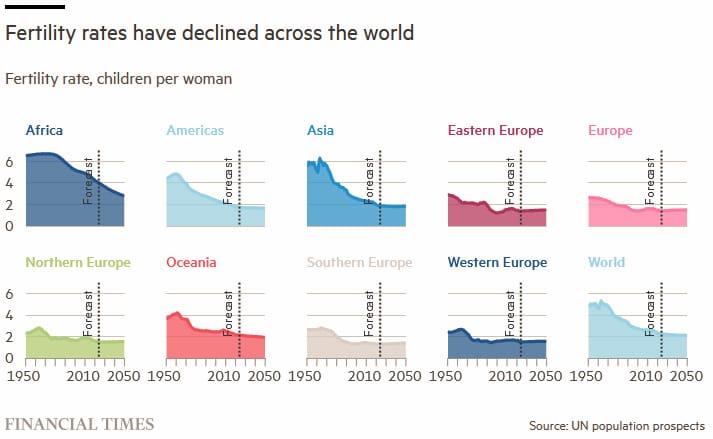

Last year was a big one: it marked the first time in history that humans didn’t produce enough babies to sustain the population:

“This doesn’t mean the global population is already falling. ‘Demographic momentum’ means that women born in the 1990s and 2000s are currently having children, while their parents’ generations haven’t yet died. Longevity, meanwhile, is increasing. So although global births are falling, they still exceed deaths. At present rates the human population will peak in around 30 years. Then start plummeting.

Economists have long predicted fertility rates would decline as countries become wealthier. But the fall over the past decade has happened in rich, middle-income and poor countries. It has also been faster than anyone predicted.”

There are consequences of population decline but not necessarily where you might think. For example, many ‘de-growthers’ like to say that fewer people will be better for the planet. But that’s not necessarily true, as economist Jesús Fernández-Villaverde points out:

“This is misguided. A gently falling population could be good for sustainability, but we’re facing population collapse and economic turmoil. Environmental concern is a ’luxury good’: we do it more when prosperous. Voters in 2050 in a country with acute budgetary problems caused by an ageing population will care a lot less about global warming.”

I would add that fewer people – especially young people – also means fewer innovators to solve our various problems, including environmental issues.

Unfortunately, it’s really hard for policymakers to reverse course. As a recent Financial Times (FT) article discovered, it’s not for lack of trying:

“Hungary’s family subsidies under the rightwing populist government of Viktor Orbán, who opposes immigration and supports the ’traditional’ family, are among the world’s most generous.

They include tax breaks that increase with the number of children — mothers of four or more pay no personal income tax — and other allowances. Total family subsidy spending exceeds 5 per cent of GDP, or more than double what Hungary spends on defence.”

It hasn’t worked: after kicking off a temporary rise in fertility, Hungary’s fertility hit a decade-year low this year, with the European nation “discovering that it is far easier to persuade one cohort of women to bear their children earlier than it is to generate a lasting rebound in births”.

There are lots of factors that contribute to falling births but the biggest is perhaps cultural norms, which can change very slowly; there’s only so much policy can do if norms have shifted towards smaller families.

But policymakers aren’t completely powerless: as Fernández-Villaverde concludes, making housing more affordable in metropolitan areas would help, as would helping to change societal structures that have “become deeply unwelcoming to large families”. He used the example of car seat mandates that make it safer for kids but also “harder to fit more than two children in a car… an instance of government policies having unintended consequences”.

Basically, it’s complicated, but I’m going to end of a somewhat positive note. While we could be in for some less-innovative and fiscally challenging times over the coming decades, fertility should be at least partially self-correcting: with fewer people, housing will become more affordable, the streets will be relatively safer, and religious groups that have disproportionately larger families will increase as a share of the population, all of which should shift norms back towards higher fertility rates. But that’s a very slow process, and in the meantime…

Time for fiscal responsibility

Population decline is global, and immigration is only a temporary fix: migrants will eventually get old and draw on fiscal resources, just like today’s elderly. So, it’s important to have the fiscal house in order or we’ll find ourselves unable to pay for a lot of things we take for granted. Vox’s Dylan Matthews recently described the problem of too much debt, from a US perspective:

“There’s no magic number at which the debt load becomes a full-on crisis. But it steadily becomes a bigger and bigger problem, and the trajectory we’re on is worrisome. It’s especially worth taking debt more seriously when other problems that deficit spending can help solve, like mass unemployment, have been fixed. Moreover, without tackling the debt problem, tackling other problems, from child poverty to housing costs to climate change, will become harder as the government has less space to spend and invest.”

In Australia, the federal government’s “spending in real terms rose 4.5 per cent last financial year, even discounting for the high inflation rate. Federal spending as a share of GDP next financial year is forecast by Treasury to be the highest since the 1980s, excluding the pandemic”.

Our states aren’t much better – in fact, many are deficit spending even greater amounts as a share of their economic output – but while debt to GDP/GSP is still low by global standards, it’s a worrying trend because the higher the ratio gets, the greater the costs:

“A heavy debt burden can impose at least two different kinds of costs. One, it can slowly erode economic growth. Two, it can in extreme cases lead to interest rates spiralling ever-upward because lenders no longer trust that they will be paid back, putting the borrowing nation in a crisis that can end in runaway inflation, default, recession, or all of the above. The risk of either is why considering deficit reduction now is probably a good idea.”

In the US, each dollar of federal deficit reduces private-sector investment by 33%, something economists call crowding out. It has very real impacts on growth, wages and all the things we want to consume in the future:

“Of course, the economic damage depends on how that dollar of deficit is spent. And conversely, how effective deficit reduction is at promoting growth depends on the details of how it’s done. University of Pennsylvania economist Kent Smetters and the team at the Penn Wharton Budget Model recently evaluated three massive deficit reduction packages, using a mix of tax hikes and spending cuts. Sizable deficit reduction, they concluded, boosts GDP by as much as 9.8 percent by 2054, and raises wages by as much as 7.5 percent compared to the status quo where debt keeps rising.”

Matthews offers five solutions, all of which sound quite reasonable so will probably have almost no chance at getting the all-important political buy-in:

- Use tax hikes or spending cuts to offset any new spending or tax cuts.

- Take growth seriously.

- Actively raise revenue and pay off debt.

- Reform entitlements, which will only get more problematic as people age.

- Ensure that per-person health spending stays roughly constant.

In Australia, we need some of those more than others. The latter two points hit especially hard, given all the troubles we’ve been having with the NDIS.

The reality of industrial policy

When you start doing industrial policy, you create powerful incentives. Instead of spending resources competing in the private sector and creating consumer surplus, firms start to spend resources to compete in the political arena – commonly known as rent-seeking. Unlike private competition, this is a zero-sum game: the subsidy is the “rent”, and firms will pay up to the amount that’s being given away to get it.

So, it should come as no surprise that the queue for the pot of gold that a Future Made in Australia has made available is already a long one:

“Caravan manufacturers, chocolate makers, software developers, gas companies and native titleholders are among the slew of interest groups putting their hands out for billions in taxpayer support as part of the Albanese government’s Future Made in Australia plan.

Economists say the requests underscore Productivity Commission boss Danielle Wood’s warning that the Albanese government’s efforts to subsidise local manufacturing could damage the economy by creating a class of low-productivity rent seekers.”

Every dollar spent lobbying – seeking these “rents” – is a wasted dollar from the perspective of society. The more firms bidding, the greater the waste – potentially more than the total value of the fund, depending on how many bidders there are and what each of them spends on their respective bids.

From their perspective, politicians aren’t spending their own money, so they don’t have much of an incentive to do what’s in society’s interest. Without adequate safeguards in place, the firms they pick to get the subsidies will not be the ones that maximise consumer surplus but whichever ones can help them get re-elected, or ensure cushy post-political boardroom jobs and consulting gigs.

Now, it’s a bit early in a Future Made in Australia’s life for any real-world examples to exist; it’s not even law yet. But in the US – the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) was passed in August 2022 – there are plenty.

Take Intel, a firm that has been badly mismanaged for decades and was the largest recipient of the Biden administration’s CHIPS grants, pocketing billions in subsidies and tax incentives. Months later, it cut 15% of its workforce – more jobs than it promised to create with the subsidies – and the market is pricing the company at “less than the value of its facilities and other assets on its balance sheet”.

Then there’s First Solar, whose “stock price has doubled and its profits have soared thanks to new federal subsidies that could be worth as much as $10 billion over a decade”. The catch? It spent nearly as much lobbying for them:

“Executives, officials and major investors in First Solar, the largest domestic maker of solar panels, donated at least $2 million to Democrats in 2020, including $1.5 million to Biden’s successful bid for the White House. After he won, the company spent $2.8 million more lobbying his administration and Congress, records show — an effort that included high-level meetings with top administration officials.”

Per watt, First Solar’s panels cost around twice as much as those from south-east Asia, and triple China. So what does an uncompetitive but expert rent-seeking firm do in such a situation? Why lobby for more protection, of course:

“In April, First Solar filed a petition with several other manufacturers to the US Department of Commerce and International Trade Commission, accusing Chinese companies of dumping solar cells in south-east Asia, where the US sources the bulk of its supply. New tariffs could reach 270 per cent depending on the company and country.

The case has divided the US solar sector, with companies accusing America’s flagship manufacturer of ‘cornering the market’ by pushing for protections that hurt its competitors and make decarbonisation more expensive.

‘First Solar’s strength really is its lawyers,’ said Jenny Chase, an analyst at BloombergNEF. ‘It’s purely about the trade wars.”

When a Future Made in Australia gets rolling, it won’t be all Intel and First Solar; there will be actual winners that emerge, not just rent-seeking legal firms masquerading as manufactures. But any analysis should keep the post hoc ergo propter hoc fallacy in mind: just because some industry received subsidies and succeeded, doesn’t mean it wouldn’t have succeeded anyway.

Fun fact

China just approved 11 new nuclear power plants at a cost of 220 billion yuan ($A46 billion), with construction to take about five years.

Assuming each reactor generates around 1,000MW, which is in-line with its existing facilities, that’s $A4.2 billion per reactor – less than half what the CSIRO estimated it would cost to build the equivalent nuclear power plant in Australia, in a third of the time.

Comments

Comments have been disabled and we're not sure if we'll ever turn them back on. If you have something you would like to contribute, please send Justin an email or hit up social media!