Friday Fodder (33/24)

Let’s jump right in this week with the July monthly inflation figures, which are getting even more difficult to interpret because of all the temporary, pre-election meddling with prices dressed up as cost-of-living support.

Prices are signals

Wednesday’s monthly consumer price index (CPI) figures came in at 3.5% in July, down from 3.8% in June. The slowdown was actually less than people were expecting and the Aussie dollar shot up nearly half a cent after the release, suggesting that, if anything, this was bad news for anyone hoping for rate cuts.

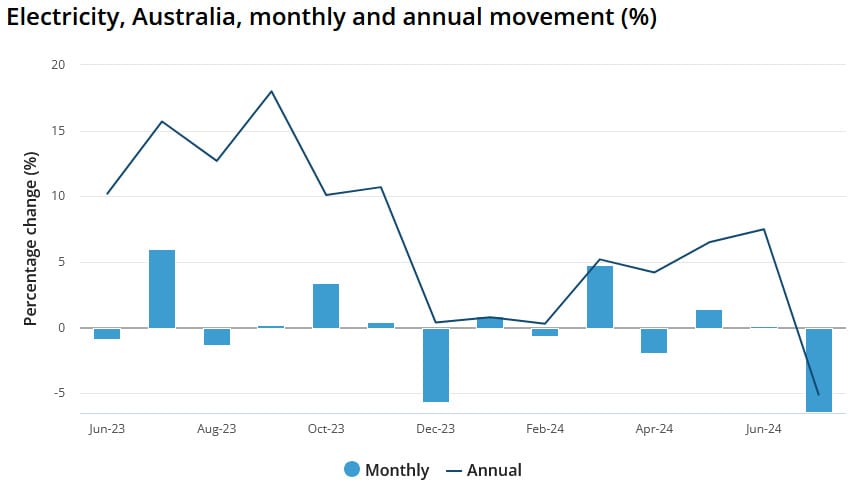

I say if anything because the monthly CPI should never be trusted as an indicator of inflation, given that it’s not measuring much. Moreover, July was an especially bad month for those seeking to gauge the Reserve Bank of Australia’s (RBA) efforts to bring inflation back down to within its 2-3% target because a bunch of big government subsidies kicked in, doing things like this to measured electricity prices:

Let’s just say electricity isn’t getting cheaper because we’ve fixed our supply problems. And because people now have more money to spend on other things, the subsidies are likely to be adding to actual inflation, not detracting from it, especially as the spending is deficit-financed (so expectations come into it – i.e., the extent to which people don’t think it will be paid off with taxes but inflated away instead).

Are we a developing country again?

One of my first posts on Aussienomics was about our inability to build. It was in the context of renewable energy, but the impetus was similar to something that happened this week: environment Minister Tanya Plibersek stepping in to prevent something from being built. Then it was a renewable energy port, now it’s a gold mine:

“Regis Resources was planning to extract up to 60 million tonnes of ore and produce 2 million ounces of gold from the McPhillamys Gold Project near Blayney.

On Friday, Environment Minister Tanya Plibersek accepted an application by a coalition of Wiradjuri elders to protect the headwaters and a section of the Belubula River from any mining desecration.

The mine’s waste storage, known as a tailings dam, was to be constructed on the river’s headwaters which is no longer possible after the minister’s decision.

In a statement, Regis said the decision impacts a critical area of the project development site and means the project is no longer financially feasible.”

Plibersek used Section 10 of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Heritage Protection Act, which gives the minister the discretion to protect an area on cultural grounds, provided an Indigenous person has an application. In this case it looks as though there was only one such application, led by Wiradjuri elder Aunty Nyree Reynolds.

But there were also several Indigenous groups in support of the project, including the Orange Local Aboriginal Land Council, “which has legal cultural authority over the area”, and “Roy Ah-See, a respected Wiradjuri leader and former chair of the NSW Aboriginal Land Council”, who said he has never heard of Reynolds and the decision “makes a mockery of my people”.

I don’t know whether the decision to block the tailings dam should have been made. But I do know that a cost benefit analysis should have been undertaken: trade-offs have to be considered, even if they’re uncomfortable, and even if it means sacrificing part of the headwaters of a river that a few people consider important.

At what point would Plibersek not have blocked the tailings dam? We know that it would have operated for 11 years and led to “$1 billion investment to build the mine, 580 construction jobs, 290 operational jobs, and $200 million of royalties to the state”.

What if the soil was worth a trillion dollars? What if it could save 50,000 lives? How large would the benefits have to be to dismiss the cultural claims and approve the project?

The fact we don’t know the answers to those questions – and that Plibersek has since doubled-down, dismissing the company’s complaints by saying “they just need to find a new location for the tailings dump” – suggests we never will.

Development economists would call that regime uncertainty:

“Even when government changes the rules in a way that seemingly strengthens private-property rights overall, the action’s specific form may jeopardise particular types of investment, and apprehension about such a threat may paralyse investors in these areas. Moreover, it may also give pause to investors in other areas, who fear that what the government has done to harm others today, it may do to them tomorrow. In sum, heightened uncertainty in general — a perceived increase in the potential variance of all sorts of relevant government action — may deter investment even if expectations shift toward more secure private-property rights.”

Jim Beyer, the chief executive of Regis Resources, told investors the decision “shatters any confidence that development proponents Australia-wide, both private and public, can have in project approval timelines and outcomes”:

“The implications of this decision are not limited to the resources industry but also to developers of infrastructure, renewable energy, property, as well as tourism operators, farmers and owners of freehold land more generally.”

And I note that there are a number of similar comments being made within the industry over the weekend and today."

Look, cultural protections are important; no one wants another Juukan Gorge situation. But the mine in question spent years clearing various state and federal approvals processes, costing tens of millions of dollars, only to be arbitrarily shut down at the last minute. If that’s not regime uncertainty, I don’t know what is.

There is no next China, Europe edition

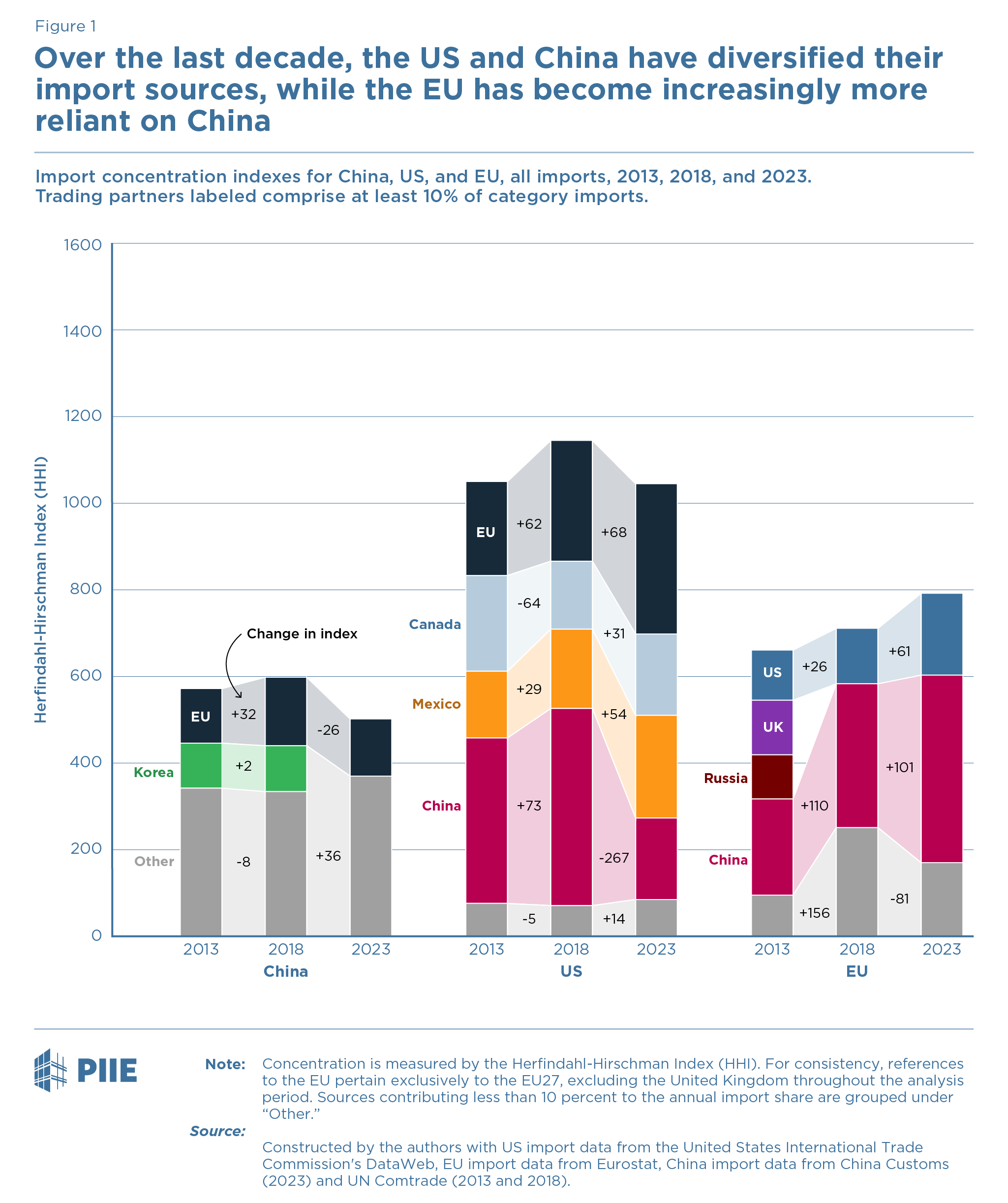

This week the Peterson Institute for International Economics released a report on China, looking specifically at the US, EU and China’s trade concentrations using the Herfindahl-Hirschman index. It found that while trade between the US and China has become less concentrated, the opposite is true for the EU and China:

“China’s import sourcing is the most diverse of the three big regions; its concentration index is substantially lower than those of the other two, figure 1 shows. Only the European Union provides more than 10 percent of the total value of China’s imports. The European Union also relies on a diverse set of suppliers; just two sources—the United States and China—provide 10 percent or more of the European Union’s import value in 2023.”

And here is figure 1:

The US is diversifying to the EU, Mexico, and other countries, but China never stopped producing the manufactured goods it used to sell to the US directly, and those still have to go somewhere. That somewhere looks to be the bargain-hunting EU. As the authors conclude, these changing trade dynamics will have implications for US foreign policy:

“Despite efforts by the Biden administration to convince the European Union to wean itself off Chinese imports, the opposite is happening. Europe has grown more dependent on China in recent years as the United States has become less so. This increasing divergence in US and European economic interests may make it harder for them to agree in the future on national security and technology policies involving Chinese imports.”

There may not be a next China, but the US looks like it may have found its China plus many. Whether it was worth the considerable cost (more expensive consumer goods e.g. from tariffs) given that it hasn’t really hurt China’s manufacturing prowess, but merely redirected it, remains to be seen.

Careful disclosures

A while back I wrote about a study that found of the three types of pay transparency – vertical (you know your manager’s salary), cross-firm (industry-wide) and horizontal (everyone in the firm knows each other’s pay) – only the first two were beneficial for workers.

It turns out that knowing everyone’s salary in your company changed the bargaining dynamic. Firms had to start paying everyone at the same level equally, regardless of their productivity, otherwise those being paid less “felt disgruntled and exerted less effort”. As a result, wage equality was achieved but through lower average pay overall.

Now there’s another paper on these unintended consequences, which found a similar effect but especially in markets that were highly concentrated:

“Whereas wage disclosure is generally expected to mitigate pay inequities and empower labour market participants through enhanced information access, this study shows that the opposite can happen… the empirical findings of this study show that wage disclosure, in conjunction with labour market concentration, can exacerbate wage suppression. This suppression is particularly pronounced in sectors with high market concentration, where firms can coordinate through periodic wage disclosure, thereby maintaining low wages.”

So, be careful with economy-wide wage disclosure laws. You might be helping retail workers, but with the same stroke of the pen could be condemning mining, utilities and aviation workers to lower wages (unless they have a high enough rate of union membership).

Climate policies don’t work

Politicians love to regulate polluters while providing transfers – subsidies – to green industries, all in the name of reducing carbon emissions. From their perspective, it’s a win-win: they get to don their hard hats every few weeks at some new green ribbon cutting event, while also observing more people driving EVs and riding bicycles.

But it turns out, most of these policies actually fail at their stated goal of reducing emissions:

“An evaluation of more than 1,500 climate policies in 41 countries found that only 63 actually worked to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

…

The study, published today in the journal Science, used an AI algorithm to sift through a database of environmental prescriptions compiled by the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, a Paris-based economic agency, between 1998 and 2020. These policies ranged from energy-efficient standards for household appliances to a carbon tax on fossil fuels like oil and gas.

The fraction of policies that worked combined financial incentives, regulations and taxes, according to the study.”

I’ve said it before and I’ll say it again.

“Economists love carbon taxes. Not because they eliminate all carbon emissions, but because they solve a market failure by correctly pricing them, sending a signal about the true cost of different products and services.”

It’s very difficult to change people’s actions with only regulations and subsidies: the former take a long time to pass and can create large, counter-productive unintended consequences (seriously: emissions regulations are what birthed the dreaded Yank Tank), while the latter can be prohibitively expensive and may end up picking many ’losers’, wasting resources in the process of achieving negligible carbon reductions.

So, if carbon reduction is the policy goal, then use prices and let people decide for themselves how to reduce their emissions in the least costly way.

Not-so fun fact

This week’s fact comes from the site formerly known as Twitter:

You might read stories about Russia’s booming economy but it won’t last.

Comments

Comments have been disabled and we're not sure if we'll ever turn them back on. If you have something you would like to contribute, please send Justin an email or hit up social media!