Friday Fodder (34/24)

Lots to cover in the Australian econosphere this week, starting with the June quarter GDP figures that confirmed Australia’s per capita recession has rolled into its sixth consecutive quarter and is officially our worst and longest such recession since 1990-91.

This is not sustainable

Wednesday’s national accounts were about as bad as expected. But that didn’t stop Treasurer Jim Chalmers claiming that it would have been even worse had his government not spent so much:

“It frankly torpedoes a lot of the free advice that we got at budget time to cut harder and harsher. That would have been a recipe for a much weaker economy. We know that from the data we have before you now.”

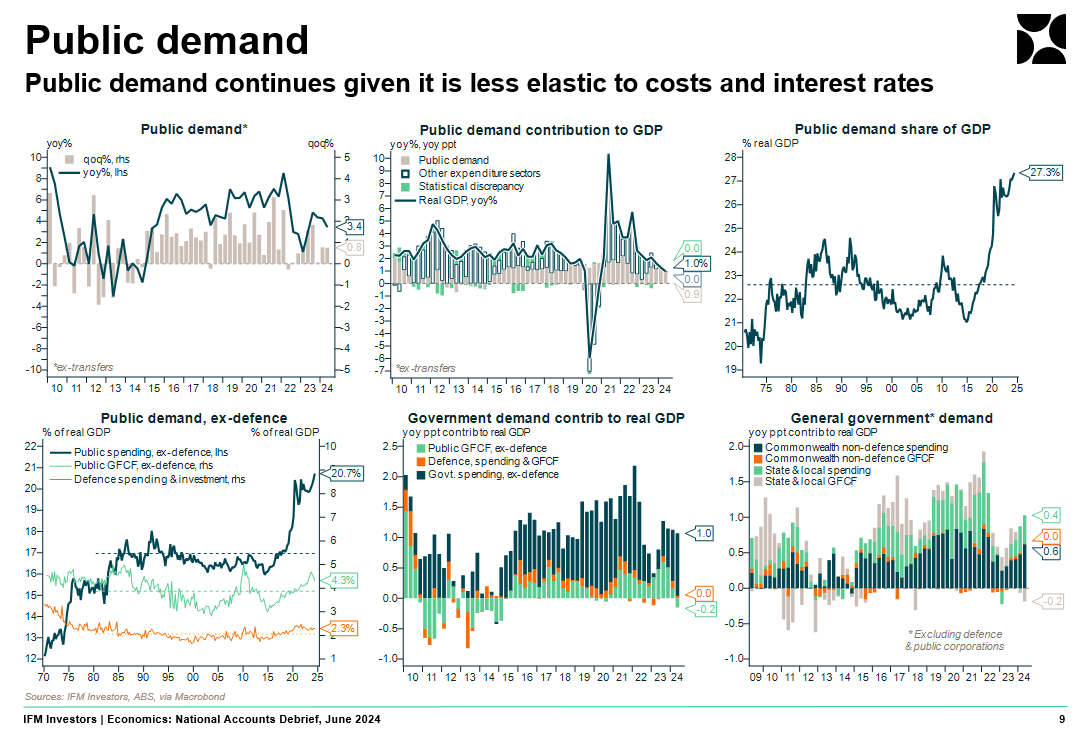

He’s technically correct. GDP would have shrunk without a huge boost from public demand:

But GDP is something governments can grow by destroying wealth, at least in the short-run. If the government built a bunch of ships and then blew them up, GDP would increase, as it only measures final production. But the resources used to build those ships are now gone and they could have been used to do something productive that not only would have raised GDP, but raised future GDP too.

That’s called crowding out. And with public demand’s share of GDP now at a record-high, there’s probably a fair bit of crowding out going on.

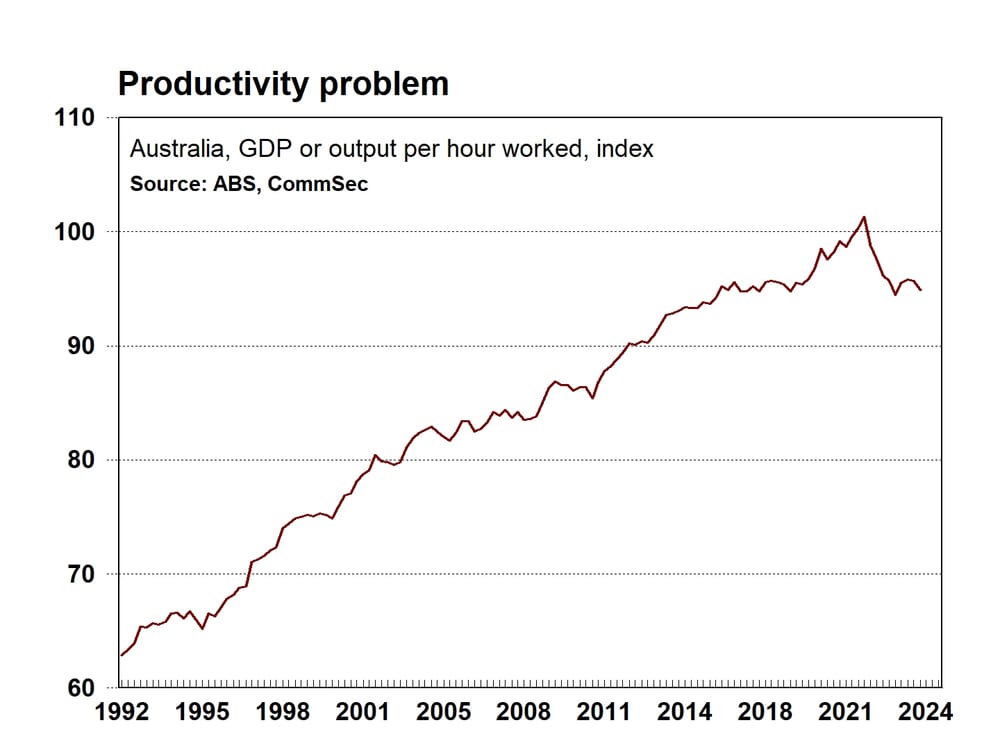

Basically just because Chalmers’ spending is causing GDP to grow, that tells us nothing about the impact of the that expenditure on the economy. For example, it may be doing more harm than good – e.g. driving inflation – if it’s coming at the expense of more productive private consumption and investment. And productivity growth is something desperately lacking in Australia:

All levels of government have squandered the recent terms of trade boom, adding to net debt and doing nothing to make Australia more competitive and productive. If we stumble into a sustained economic downturn at the same time as the terms of trade falls, we’re extremely vulnerable.

Confidently wrong

How likely are we to get good, productivity-enhancing policy reform when the Treasury Secretary, Steven Kennedy, needs to brush up on his economics? During a speech this week, Kennedy discussed how great it was to have so much more data for policy-making. Then he said:

“We need to be humble about what we know and what we don’t know, acknowledge the limitations of our evidence, and acknowledge that evidence evolves and we learn more as we go.”

Good; we definitely need more of that. But then he went and gave an example:

“It is worth remembering that it was conventional wisdom that a higher minimum wage resulted in fewer jobs — then in 1994, economists David Card and Alan Krueger used a natural experiment to show that, in the real world, this does not always happen.

Since their groundbreaking work, a significant body of literature has largely confirmed these findings.”

I know that study well. I also know that in 2000, the same journal that published it also published a reply that found “severe measurement errors” in the original study’s data, raising “serious doubts about the conclusions”.

Since then, the “significant body of literature” is still unsettled. If you look around, you can find minimum wage studies showing no effect on employment. But you can also find plenty that find big effects. Meta analysis has generally confirmed that minimum wages produce negative employment effects, but the results depend on what the studies are looking at: for example, what industry; is it national, or state; was the economy in a recession, or a boom; what was the magnitude of the increase?

There’s also a question of publication bias: perhaps it’s mostly exceptions to the theory on minimum wages that get published because no journals are interesting in publishing a study that says yes, water does flow downhill!

So, Kennedy ought to take his own advice and be humble about what he thinks he knows, especially when that knowledge runs counter to what economic theory predicts. That is, if you raise the minimum wage above the market wage you will cause disemployment effects, especially among the least productive workers, e.g. teenagers.

Destruction is not profitable

China’s leaders are getting desperate:

“Shanghai will grant a record CNY4 billion (USD562 million) in subsidies to support the trade-in of consumer goods, such as cars and home appliances.”

You might recall the Gillard government also did this in 2010. But the economics behind such “stimulus” measures is overwhelmingly negative. They cause large deadweight losses because the money raised to pay for them comes from future taxes, which distorts activity – a ballpark estimate is around 30% of the amount raised. They also add to debt to destroy perfectly good cars and appliances – Bastiat’s broken window fallacy.

Sure, maybe all of those costs are justified if your economy is that lacking in aggregate demand. But then even if that were true, these programs don’t actually stimulate:

“A key rationale for fiscal stimulus is to boost consumption when aggregate demand is perceived to be inefficiently low. We examine the ability of the government to increase consumption by evaluating the impact of the 2009 ‘Cash for Clunkers’ program on short and medium run auto purchases… The effect of the program on auto purchases was significantly more short-lived than previously suggested. We also find no evidence of an effect on employment, house prices, or household default rates in cities with higher exposure to the program.”

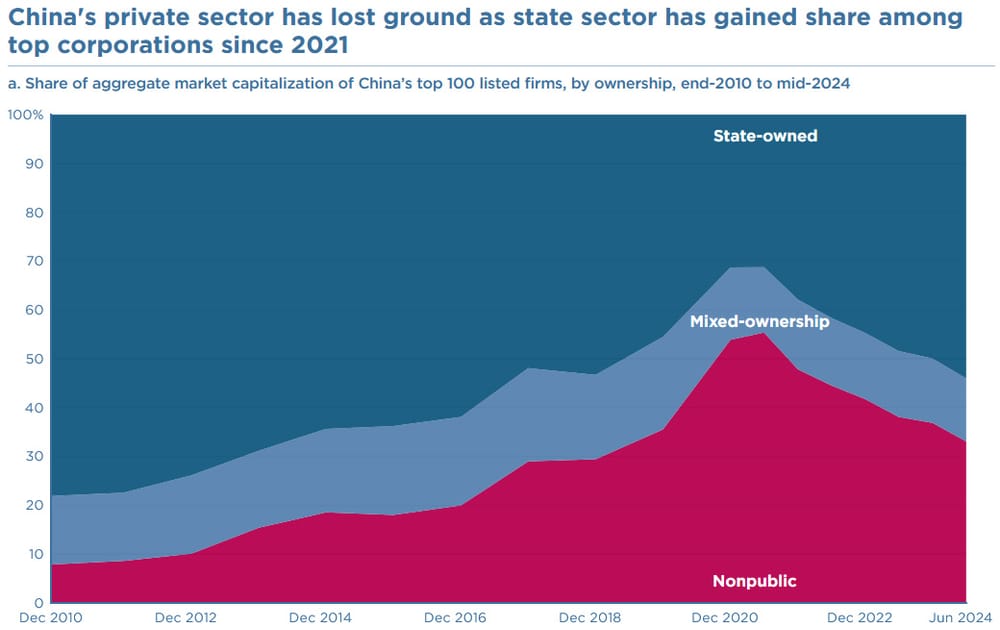

If the Chinese government wants to know why its economy is so weak, it only needs to look in the mirror:

“Privately-owned firms’ share of market capitalisation among China’s 100 largest listed companies shrank from a peak of about 55 percent in mid-2021 to just 33 percent at the end of June this year, a decline of more than 40 percent in only three years (see panel a). At the same time, the share of state-owned enterprises, namely those majority owned by the Chinese party-state, rose steadily from less than one-third to about 54 percent.”

Xi Jinpingonomics at work.

Beware the consequences

The Australian government wants to tax unrealised gains on superannuation balances above $3 million. Apparently, Joe Biden and Kamala Harris want to do something similar but only for the very wealthy – those with assets worth at least $US100 million.

Australia’s is much worse because it will, over time, affect all households (the threshold is not indexed). But both policies are basically drawing from the same bad ideas and come with large possible unintended consequences, such as taxing entrepreneurship too early, or adding to fiscal volatility because asset values change for lots of reasons unrelated to income, including interest rates.

Interestingly, Norway has had a tax on unrealised gains for a while:

“Many countries in Europe have taxed unrealised gains, but later removed it because all of its harmful side effects. Norway is one of the few countries that still has a wealth tax, and it has been a total disaster.

Since the left wing government increased the wealth tax to ~1,1% and dividend rates to 37,8% two years ago ~80 of the top 400 tax payers have left the country. Representing ~40% of the wealth of those top 400. And it’s *not* because of high marginal taxes in general, it’s basically only because of taxes on unrealised gains.

Earlier stage entrepreneurs are now also pre-emptively moving or considering moving even *before* they start companies. I left Norway after we had raised a Series B and I was about to got a wealth tax bill many times my net salary, with no other options for dividend or liquidity on my start-up shares.

Outside of oil the Norwegian economy is now stagnating with no productivity growth.”

Australia already penalises entrepreneurship outside of ‘captive’ industries such as mining and finance because we tax productive activity (e.g. income) too heavily. Yet here we are in a productivity crisis, and this is the model our government wants to move us closer towards? If you want people – especially rich people – to pay more tax, there are far less destructive ways of going about it than taxing unrealised capital gains.

A deep, self-inflicted wound

Harvard’s Ed Glaeser penned an excellent essay in the NYT this week that is just as applicable to Australia as it is the US. Basically, our housing shortage is “a deep, self-inflicted wound” that “has its roots in regulations enacted by innumerable municipalities [councils]”:

“America wasn’t always like this. In the 1920s, New York City was affordable to its poorer residents because it permitted the construction of as many as 100,000 units a year. After World War II, builders like the Levitt brothers kept costs down by applying mass production techniques to new housing. But in those early days, builders had a distinct advantage: Existing residents didn’t control the permitting process, and zoning still accommodated growth. Fear of change, especially change to one’s neighbourhood, is constant, but the ability of residents to block projects has since exploded.”

Basically, the most desirable suburbs have seen the least housing growth because “residents have made it particularly difficult to build in the most productive parts”. It’s why suburbs like Mosman, just five kilometres from down town Sydney, are adding housing supply at just 0.2% per year. Meanwhile Sydney as a whole is growing at nearly 3% per year. Here’s Glaeser again:

“GDP is much lower than it would be if people could move to where the jobs pay the most. Areas with the most upward mobility limit building the most, which makes America more permanently unequal. We also make it easy to build in areas that have high carbon footprints because it is too hot or too cold, but we make it hard to build in areas where carbon emissions are naturally low because of mild climates.”

What should be done about it? Use incentives, of course:

“The goal should be to nudge state legislatures to reduce the ability of communities to zone out change.

For example, the legislation could establish minimum construction levels over three years for all counties with median housing values above $500,000. States with high-price, low-construction counties would have to figure out how to overrule local zoning codes themselves or lose federal transportation funding.”

Our states need to do more to bring local governments into line, and the federal government should consider using some stick along with the carrot of paying them to build “affordable” and “sustainable” houses, which can be counter-productive because they make market-rate housing construction less profitable. Housing supply does in fact trickle down; any new housing – even “luxury” – will free up a house on the next rung down, and so on. Basically, new housing construction of any kind helps the entire income distribution!

Fun fact

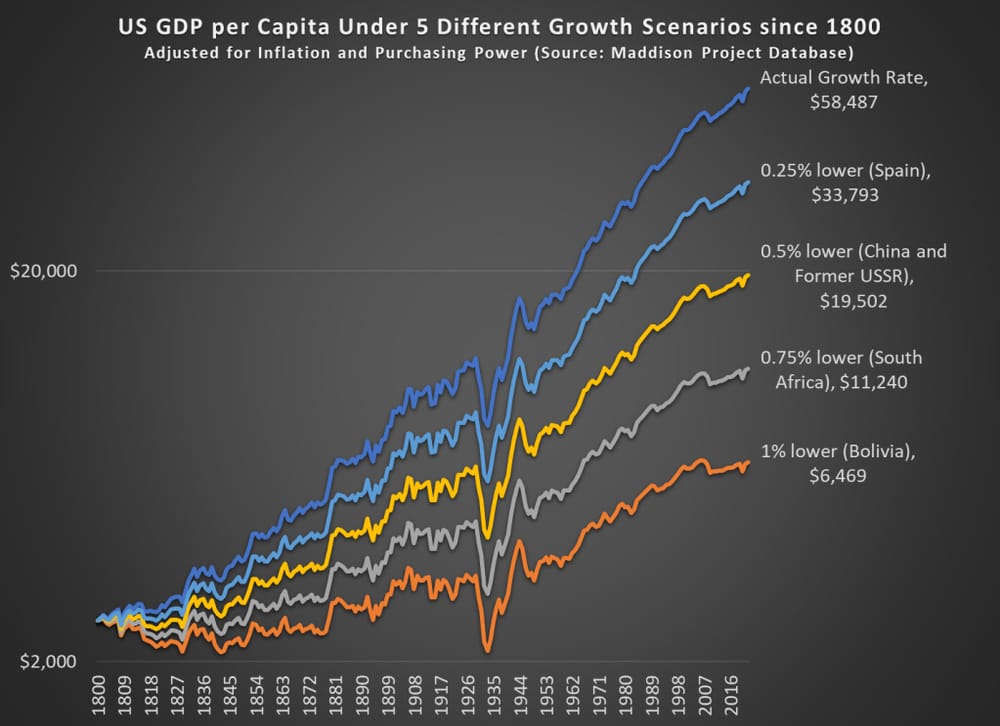

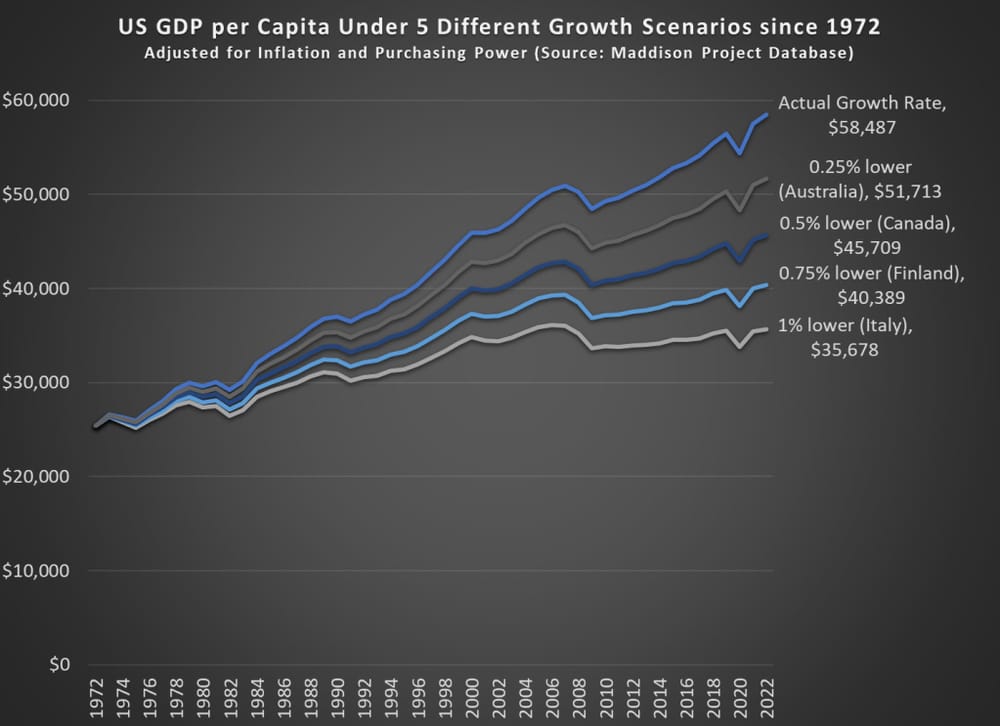

Growth matters. A lot:

“What is very interesting, I think, is that if our [US] growth rate had been just 0.25 percentage points lower per year since 1800, we would be about where Spain is. Now, Spain is certainly a fine, modern developed country (they rank 34th of the 169 MPD countries). But Spain’s growth has not been spectacular lately. Average income in Spain is almost half of the US today (purchasing power adjusted!), which is another way to say that just 0.25 percentage points lower over 222 years reduces your growth rate by half.

…

What if we perform the same analysis for a shorter time horizon? If we go back 50 years to 1972, the effects are not quite as dramatic, but still visible. Our cumulative annual growth rate since 1972 has been a bit higher than the long-run average, around 1.68%. Under these four alternative growth scenarios since 1972, the comparable countries don’t sound so bad. It probably wouldn’t be a huge deal if we were only at Australia’s level, losing just about a decade of economic growth. But it would be a huge failure if we were only at Italy’s current level of development. Under that 1 percentage point lower growth scenario, we would have had no net growth since about year 2000, which has roughly been the case for Italy.”

Comments

Comments have been disabled and we're not sure if we'll ever turn them back on. If you have something you would like to contribute, please send Justin an email or hit up social media!