Friday Fodder (43/24)

I’m travelling back to Australia this weekend so may not have time to send something out on Monday. If I don’t, rest assured that normal service will resume on Tuesday.

In the meantime, it would mean a lot if you would please fill out this short, anonymous reader survey about Aussienomics. It’s just six questions, half of which are multiple choice so should take less than a minute of your time.

With that out of the way, on to this week’s Fodder!

The best case

I’ve written a fair bit about what a Donald Trump 2.0 Presidency might mean for Australia. What we don’t know is just how strong are his convictions on the various policies announced during the campaign. Trump is officially the oldest President ever to be elected, and having served a term already, doesn’t have to worry about re-election. The Republican party also has a majority in the House and Senate, as the Joe Biden-led Democrats did for the first two years of their term.

So, the US will be getting something close to pure Trump, whatever that entails, for at least two years.

The good news is Trump has already announced that warmongers Nikki Haley and Mike Pompeo will not be a part of his next administration – although that could be bad news for the AUKUS agreement, given Pompeo’s vocal support.

Trump also revealed that Elon Musk and Vivek Ramaswamy will lead a new “Department of Government Efficiency” (DOGE, like the meme cryptocurrency), which he called “The Manhatten Project of our time”.

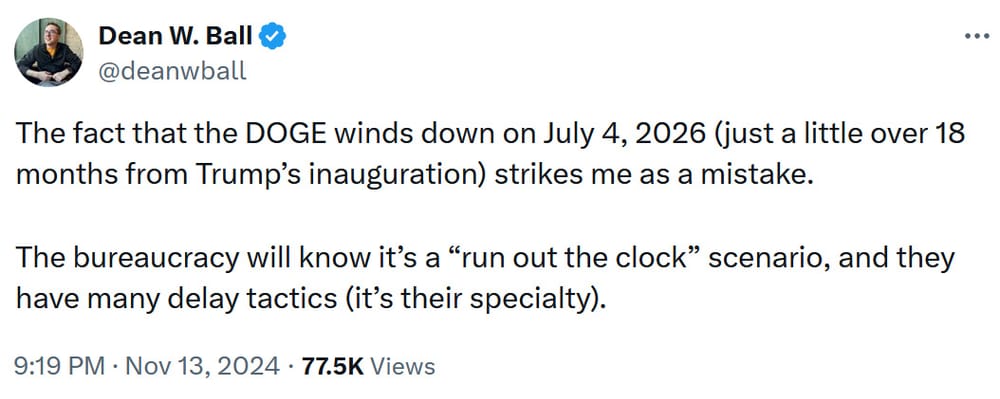

Economic reform is of course critically important, but I think Trump might be overselling this one: navigating the vast federal and government bureaucracy, not to mention the thick web of regulations and interconnected interest groups, is no easy task.

I think Musk will find the task much more difficult than he has experienced in the private sector; it would be like having to transform NASA instead of creating SpaceX from scratch, and all in just two years:

Best of luck to him. That’s also the end of the good news, with mass-deportation advocate Tom Homan to serve as Trump’s “border czar”. If he even comes close to fulfilling that goal, it will come with potentially large human and economic costs.

As for trade, that’s still anyone’s guess. But given that it’s one of the few policies Trump truly believes in, some kind of global trade war kicking off next year seems like an inevitability. The only question is how extreme it is, with economist Alex Tabarrok noting that there’s still time for Trump to soften his stance, with the “best case” being:

“Moderate tariff increases on China. No Chinese electric cars for us. But drop the ’tariffs on everything’ language. He can always say his rhetoric was a threat to get other countries to lower their tariffs. Let’s instead talk tough against our enemies but shift toward ‘friend-shoring’, maintaining or even lowering tariffs with allied nations, such as Canada, Europe, and possibly India, as part of a broader strategy to contain China’s influence.”

Tabarrok’s co-blogger Tyler Cowen was less confident, taking Trump at his word:

“Trump has promised to impose stiff tariffs of up to 60% on China, as well as lower tariffs on other trading partners, and some members of the conservative intelligentsia are cheering him on. They make several arguments, but at least one is increasingly tenuous: that 19th century tariffs, which reached 35% in the 1890s, helped build the US into an industrial power.

A new paper from the National Bureau of Economic Research shows that tariffs probably did more harm than good. Using meticulously collected industry-level and state-level data, the paper traces the impact of specific tariff rates more clearly than before. The results are not pretty.”

Trump is a notorious non-reader, so an academic study is unlikely to persuade him. Really it’s all going to come down to how much of what he announced was purely a negotiation tactic versus a legitimate policy goal, along with who he appoints to the remaining key positions in his administration. Specifically, whether economic quacks like Peter Navarro make a return or are sent packing with Haley and Pompeo.

As for the impact on Australia, Treasurer Chalmers revealed “that we should expect a small reduction in our output and additional price pressures, particularly in the short term”:

“But specific features of our economy – like a flexible exchange rate and independent central bank, would help mitigate against some of this.”

To be clear, tariffs aren’t inflationary. What they tend to do is cause a one-time increase in the price level because the amount of goods and services that can be bought for a given stock of money falls. But the rate of inflation is unlikely to be affected by tariffs alone, and the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) is likely to simply ’look through’ the temporary effect, just as it looks through one-off changes due to policy decisions, e.g. the GST or ‘cost of living’ subsidies.

The end of polling?

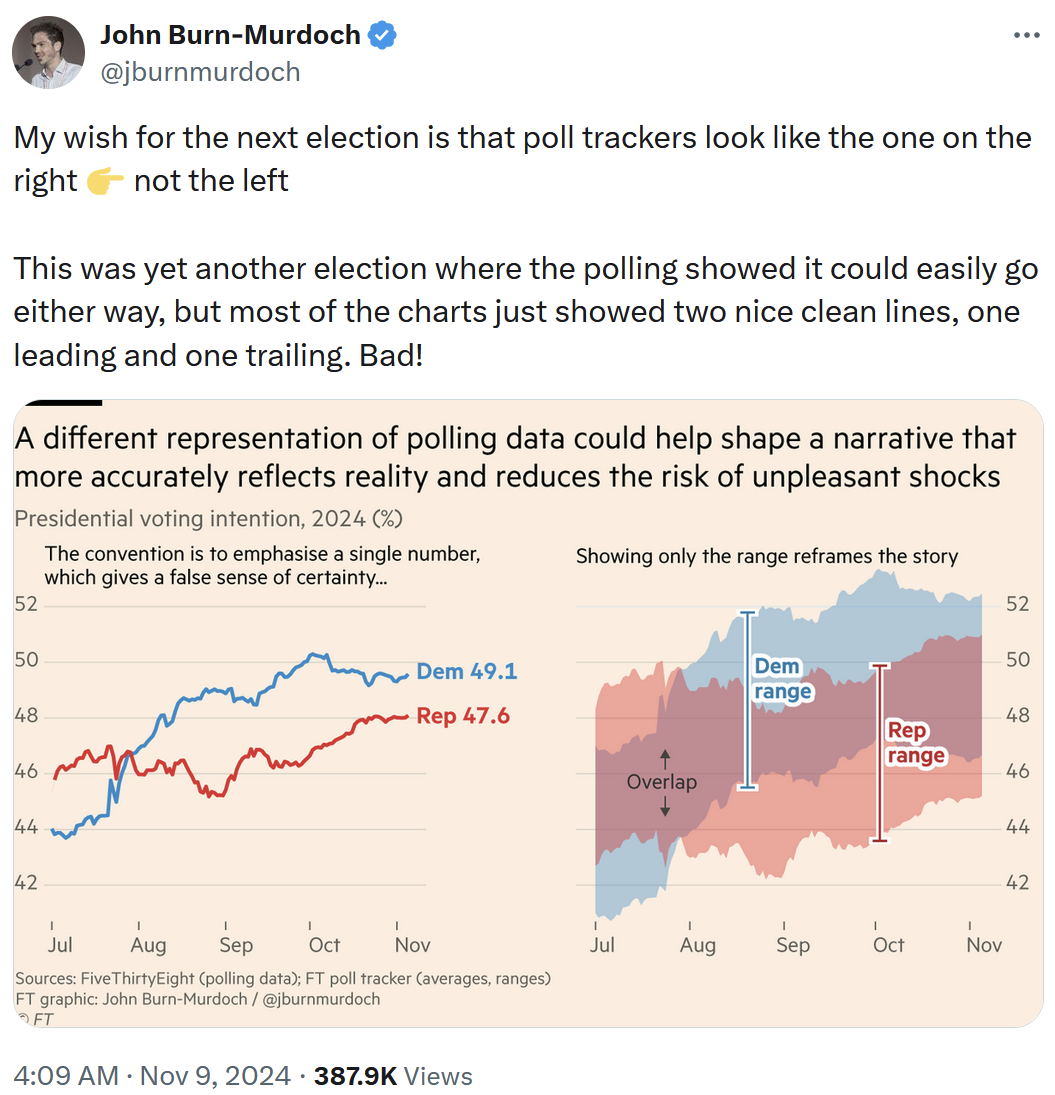

Polls performed poorly at the US election last week. Indeed, if you traded on Nate Silver’s “Silver Bulletin” model’s predictions, you would have lost money regardless of who won the election.

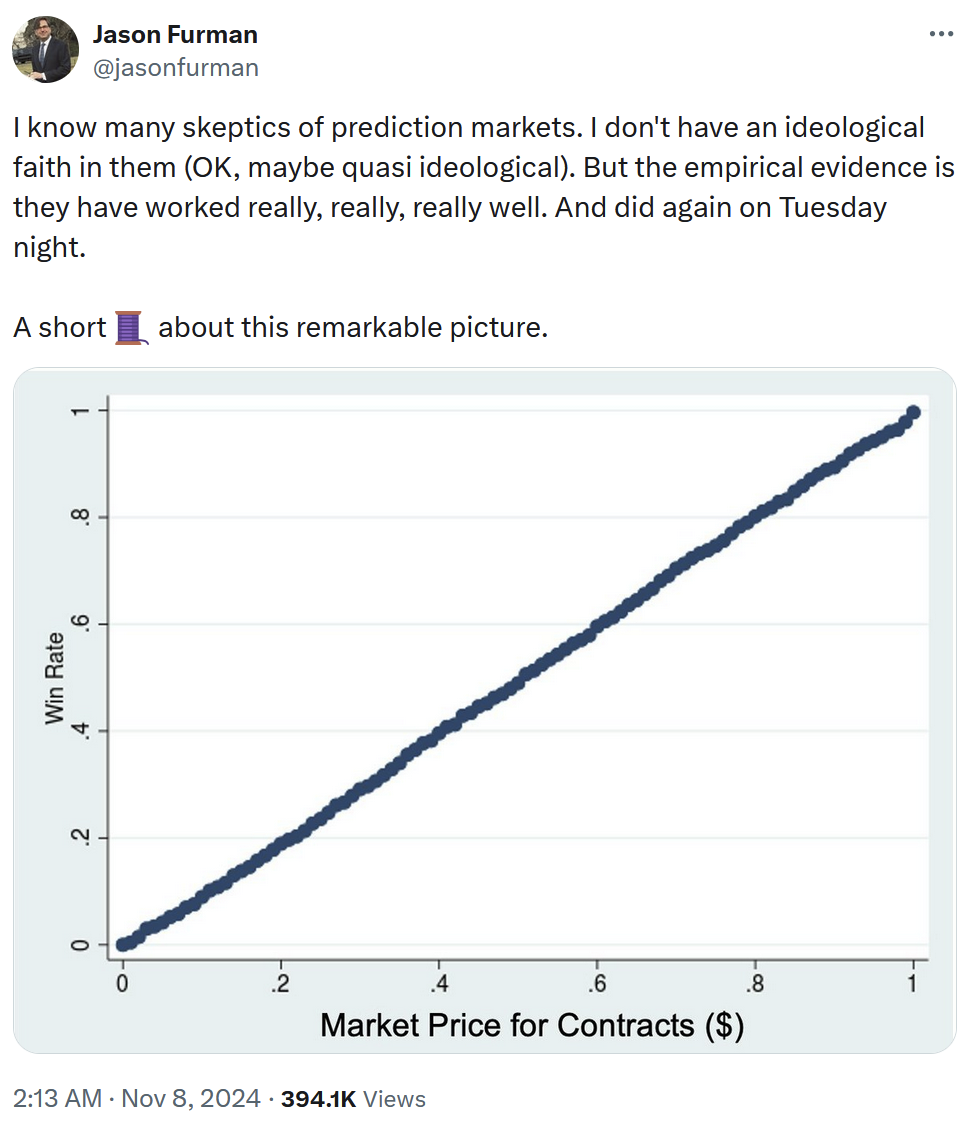

Meanwhile, prediction markets performed admirably and had Trump leading the entire time. They were also quick to ‘call’ the election, moving heavily in favour of Trump hours before the major media outlets were even willing to consider calling various states.

That shouldn’t have come as a surprise. Prediction markets are really good at… predicting stuff:

But all is not lost for polling. The anonymous French trader who correctly made huge bets on Trump was doing so armed with… polling data! The difference between the Frenchman known as Theo and Nate Silver is that rather than running ‘80,000 simulations’ with junk data, Theo went out and commissioned his own ’neighbour polls’:

“Theo used a polling approach he called the ’neighbour effect’. Instead of asking pollsters whom they intended to vote for, he asked them whom they believed their neighbour would vote for.

The reason for this approach was that most people may feel reluctant to reveal their own political leanings but are more open to guessing the political preferences of those around them. This approach also relieved respondents from the pressure of sharing their own views and could be seen as a light-hearted exercise.

Theo’s approach stemmed from what he perceived as bias within the traditional polling system. He believed that mainstream polls underestimated Trump’s popularity, particularly in swing states. His commissioned surveys further revealed that Trump’s support was stronger than traditional polls suggested, reinforcing his confidence in his unconventional bet.”

Perhaps we’ll see pollsters update their methodology after Theo’s big win last week. That, and acknowledge that there are huge ranges obscured by the simple line charts used in the media:

AI’s first major victim

It turns out that AI – large language models (LLMs) – are so good at helping students that “homework help” provider Chegg is going broke:

“Suddenly students had a free alternative to the answers Chegg spent years developing with thousands of contractors in India. Instead of ‘Chegging’ the solution, they began cancelling their subscriptions and plugging questions into chatbots.

Since ChatGPT’s launch, Chegg has lost more than half a million subscribers who pay up to $19.95 a month for prewritten answers to textbook questions and on-demand help from experts. Its stock is down 99% from early 2021, erasing some $14.5 billion of market value. Bond traders have doubts the company will continue bringing in enough cash to pay its debts.”

But it’s not all sunshine and lollipops for LLMs, which are having trouble scaling:

“OpenAI’s next flagship model might not represent as big a leap forward as its predecessors, according to a new report in The Information.

Employees who tested the new model, code-named Orion, reportedly found that even though its performance exceeds OpenAI’s existing models, there was less improvement than they’d seen in the jump from GPT-3 to GPT-4.

In other words, the rate of improvement seems to be slowing down. In fact, Orion might not be reliably better than previous models in some areas, such as coding.”

The response to this limitation from those in the AI-hype industry was to simply declare that artificial general intelligence (AGI) is already here. Which is exactly what the incentives would suggest they do, given a declaration of AGI would allow OpenAI “to get out of the Microsoft contract and have leverage to renegotiate compute prices”.

Look, I think LLMs are going to be economically impactful, and Chegg won’t be the only company completely uprooted by the innovation. But diminishing returns are here; LLMs can’t continue scaling exponentially with the same exponent. For most, that means a more gradual adoption, slowly working out how to incorporate the underlying technology into their existing workflows while also trying to discover new productivity-enhancing applications for it. Diffusing the technology will take much longer than inventing it did.

Breaking the science cartel

“Contrarian scientist” Emil Kirkegaard recently wrote about the… interesting process that is academic publishing:

“Scientists submit papers to journals for publication. This means they start the peer review process. The first step is whether the handling editor rejects it immediately, which is called a desk rejection. If not, the editor then picks some ostensible experts to review it, meaning that they read the manuscript and give their opinion about what to do with it… This process takes about 6 months, depending on the journals. All of this labour is unpaid, except the editors usually get a small salary.”

Meanwhile, the journals charge the same scientists “extremely expensive” subscription fees, paid by their universities (via taxpayers), “because it’s a natural oligopoly with a few publishers owning most of the market”.

Those fees have grown several times faster than overall prices because scientists don’t have much of a choice, or an incentive to give themselves a choice:

“To get hired and promoted in academia depends on publishing in so-called high-ranked journals (high ‘impact factor’). Those are the older, generalist journals that get a lot of attention (readership), and most importantly, citations (references from one scientific paper to another). As such, the journals that happened to get into an elite position tend to stay that way since the scientific want to keep publishing in them for selfish career reasons. The publishers know this, so they can keep arbitrarily increasing the price, which they do.”

That would perhaps be OK if the articles published in those journals were of a higher quality, but the evidence suggests they’re not.

So, what can be done about it when “it’s in everybody’s self-interest to keep publishing in these highly ranked journals”? Kirkegaard suggests the government could step in. For research that uses government-contributed funds:

- The research must be open access (from day 1). Many universities and research agencies across the world already have such mandates.

- The publication fee must not exceed X USD, where X is e.g. 100. Importantly, the rest cannot be paid by 3rd parties. Otherwise, the universities would just pay this as a cost of doing business (they also want to publish in ’top’ journals because university rankings depend in part on these).

- The research materials must be public as well, including the data, questionnaires, computer code and whatever else is needed to evaluate the work. This is to make sure the public gets the most science for the money. Other scientists can reuse materials for other research. It also helps discover and prevent fraud because fraud is often proven when the data are analysed by third parties.

Sounds reasonable to me.

Fun fact

Comments

Comments have been disabled and we're not sure if we'll ever turn them back on. If you have something you would like to contribute, please send Justin an email or hit up social media!