Getting serious about housing, ending the Future Fund, the latest bird flu, just tell the truth, and lessons from the NBN

I trust everyone’s nice and refreshed from the summer break! Lots of interesting things to discuss today, starting with some positive-sounding housing policy news from NSW.

Potentially good news on housing

The NSW government and the opposition are getting serious about housing:

“NSW Opposition Leader Mark Speakman wants the state Labor government to hold a bipartisan roundtable to fix the ‘broken planning system’, which he says has not undergone wholesale change for 45 years.

NSW Premier Chris Minns has responded by saying he agrees that the Environment Planning and Assessment Act [EPA], the unruly 327-page tract that governs planning law in NSW, is ’nowhere near fit for purpose’.”

The 1979 EPA, a version of which exists in all Australian jurisdictions, is one of the most unfortunate institutional imports from Britain. While well-intentioned and full of terms like “sustainable development” and “community participation”, in practice it created a complex regulatory landscape and empowers NIMBYism, preventing the ability of supply to respond to changes in demand.

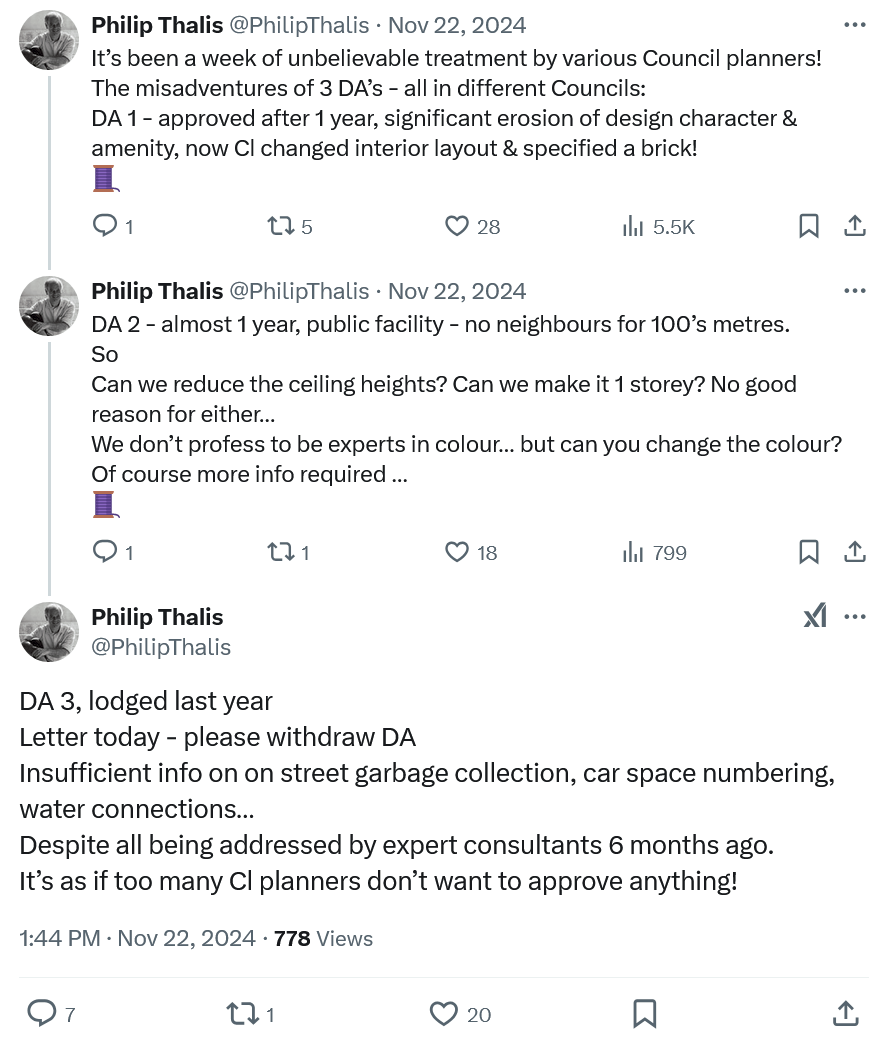

Examples like this, which are enabled by the EPA, are all too common:

Unfortunately, fixing the EPA will be easier said than done:

“The problem is getting everyone to agree on what the new laws should look like.

While some developers complain about different zoning regulations across individual councils, for example, MPs and the local government sector are unlikely to support changes curtailing local planning instruments.”

If the EPA can’t be fixed because the political opposition is too strong, then tinkering on the margin is likely the best approach. For example, the state government could pass legislation that eliminates minimum parking requirements, eases height and lot size limits, or stops councils from weaponising heritage protections, all of which can have immediate, positive impacts on the amount of housing construction.

It’s time to end the Future Fund

At the risk of sounding like a broken record, the Future Fund is no longer fit for purpose:

“Department of Finance documents prepared between July and November last year highlight that Dr Chalmers and Finance Minister Katy Gallagher not only want the Future Fund to consider national priorities in its investment decisions but also in the ongoing management of its investments, including ‘influence through voting rights’.”

Since its inception in 2006, the Future Fund has underperformed the ASX200 net total returns index despite having a swath of special privileges unavailable to normal investors. Now it’s not only going to “invest” in the government’s priority areas – which are by definition not aligned with maximising returns, or it would have already invested in them – but it’s also going to meddle in the affairs of private companies through its voting powers.

Instead of creating the Future Fund, then-Treasurer Peter Costello should have simply returned the funds to taxpayers as a dividend, boosting long-run growth by expanding the size of the productive part of the economy (the government had no debt). Even a slightly faster rate of growth would have made future pension liabilities more manageable because of the power of compounding:

- For example, between March 2006 and March 2020 the economy grew by 43.7%, or 2.8% per year. If that rate was instead 3.0% per year, the economy would have been 3.2% larger in 2020 than it actually was, making it easier for future taxpayers – who are much wealthier than 2006 taxpayers – to absorb the cost of the unfunded pensions. The longer we go, the bigger the effect.

But hindsight is 20/20. Now that the Albanese government has undermined whatever neutrality existed within the Future Fund – its quarter of a trillion dollars under management will be used to politicise the profit and loss system, allocating capital to favoured uses that will reduce long-run efficiency, employment and wealth (the reverse of the dot point above) – the need to dissolve it is greater than ever.

Wind it down, free up its 278 well-paid and highly skilled employees to work on more productive endeavours, and use the proceeds to eliminate a quarter of the federal government’s gross debt, on which we’re paying considerable interest each and every year.

How big of a deal is H5N1?

The latest strain of bird flu, H5N1, is causing chaos in the American cattle industry:

“Nearly 700 herds in the state [of California] — or 71 percent of all herds — have caught H5N1 since late August, forcing Governor Gavin Newsom to declare a state of emergency and the government to announce new testing.

While California, the nation’s top milk-producing state, has the most infections in dairy herds, more infections were reported in Michigan, and the number of confirmed human cases has inched closer to 70, according to health officials.”

Australia recorded its first human case of H5N1 late last year in a traveller from India, but has otherwise been unaffected. But if that were to change, how bad could it get? Enter Scott Alexander, who after a bit of history and examination of various prediction markets wrote:

“I conclude that the most plausible estimate for the chance of an H5N1 pandemic in the next year is 5%.

Interestingly, 5% is about the base rate for pandemic flus per year: five in the past century = one per twenty years = 5% chance per year. Isn’t it surprising that we’re still at the base rate when we can see a dangerous-looking flu virus spreading through the types of animals that have caused pandemic flus in the past?

Part of the answer is that we’re not - in addition to the 5% chance of H5N1, we have to add the chance of some other pandemic flu. This probably isn’t 5% on its own; scientists monitor flu strains closely, and they haven’t found any others which are giving off as many red flags as H5N1. Still, something could always come out of left field. Maybe we should add a 2.5% chance of some other strain, for a total of 7.5% chance of a flu pandemic (ie beyond normal seasonal flu) next year.”

As for how severe it might be:

“After reading the arguments from each camp and talking them over with superforecasters, I think, regarding the infection fatality rate of a future H5N1 pandemic:

30% chance it’s about as bad as a normal seasonal flu

63% chance it’s between 2 - 10x as bad (eg the Hong Kong Flu of 1968)

6% chance it’s between 10 and 100x as bad (eg the Spanish Flu of 1918)

<1% chance it’s more than 100x as bad (unprecedented)

If you multiply the 5% chance of an H5N1 pandemic per year by the 7% chance of severity ≥ Spanish Flu, you get an 0.35% chance of a Spanish Flu level pandemic this year - one in three hundred.”

The good news is there’s already a H5N1 vaccine for chickens and humans, and could be one for cows soon enough. The bad news is that “a little-known virus called human metapneumovirus (HMPV)… is overwhelming some hospitals in China and prompting people to wear face masks again”.

Gulp.

The importance of telling the truth

On the subject of pandemics, there’s a lot to be learned from COVID. Specifically, the response of public health officials who, having declared themselves to be the sole arbiters of truth, repeatedly flip flopped on the ‘advice’ they provided to the public. Instead of being honest with people, they regularly bent the truth to protect us from ourselves.

Examples are aplenty, such as when they claimed that masking does nothing (when they were secretly worried about a shortage), only to then do a 180 and mandate masks. Or when they held firm on the theory that the virus was spread by contact, not aerosols, leading to the disaster that was the Victorian hotel quarantine breach and a world-leading lockdown. Or when they mandated outdoor mask usage and banned the beach, despite ample evidence pointing to indoor, not outdoor, transmission.

All of those decisions, which were supported by “the science”, undermined trust in the officials themselves. As a recent podcast between economists Russ Roberts and Emily Oster lamented, those attitudes did serious – and lasting – damage to trust in public institutions:

“This came up a lot in COVID when information was coming out at all times and public health officials were changing their advice quite frequently, but never really explaining: Why? Like: What new information did you learn that made you do this?

And that’s a way that people–changing your mind without explaining is really a way to lose people’s trust, because they’re, like, ‘You told me to do a thing before. That turned out to be wrong. Why is this thing right now?’ And, I think if we had said, ‘We’re not sure. Here’s how we’re going to learn about it more, and we’ll come back and tell you later what we’ve learned and maybe it will change,’ I think that would have been a way to pull more people along.”

What public officials who refuse to tell the truth never learn is that people do learn. And when the official advice is perceived to be worthless, they turn to other sources – Instagram, TikTok, X – where algorithmic bubble-think often leads them down conspiratorial rabbit holes where they get much worse – but honest – advice from people like Robert F. Kennedy Jr, Trump’s nominee for Secretary of Health and Human Services.

Oster recommends that public officials need to be better at acknowledging and explaining their uncertainty. There is no “the science”:

“One of the pieces of the advice–if anyone were ever to ask me, ‘What would you have public health invest in?’ I think one of the things I would have them invest in is this kind of, like, translation and explanation. How can you make it vivid to people? How can you explain uncertainty? How can you help them understand data? That it’s not magic: but it is hard. And it’s a different skill than producing the research. It’s explaining the research.

And, I don’t think it’s crazy to imagine that being something that public health authorities invested in learning more about and figuring out. What resonates with people? Do they like graphs? Hope so. Built my whole life out on that idea.”

All up it was an interesting conversation about everything from the pandemic and vaccines to the fluoridation of water and raw milk. Do give it a listen.

Lessons from the NBN

I’ve long been interested in Australia’s National Broadband Network (NBN), which I’ve described as “a costly mistake”. So I keenly read a new post by David Walker, who outlined his “12 lessons from the weird, unnoticed end of Australia’s bitter broadband war”.

Here’s a small sample:

- Almost none of the cited benefits of superfast broadband has come to pass, and many (education, health and power management) were overstated.

- Technology can shrink bandwidth needs as well as expand them. Even 4K video can now be compressed into 25 megabits per second or less.

- Governments should not try to provide, without good reason, an inflated level of infrastructure just because they vaguely feel that many people might use if they got it.

- Governments should think twice before demanding that service be uniform across the nation.

Reading Walker’s essay I couldn’t help but think about the Albanese government’s ongoing renewable energy transition, which makes many similar “straight-line projections of costly technologies”.

Fun fact

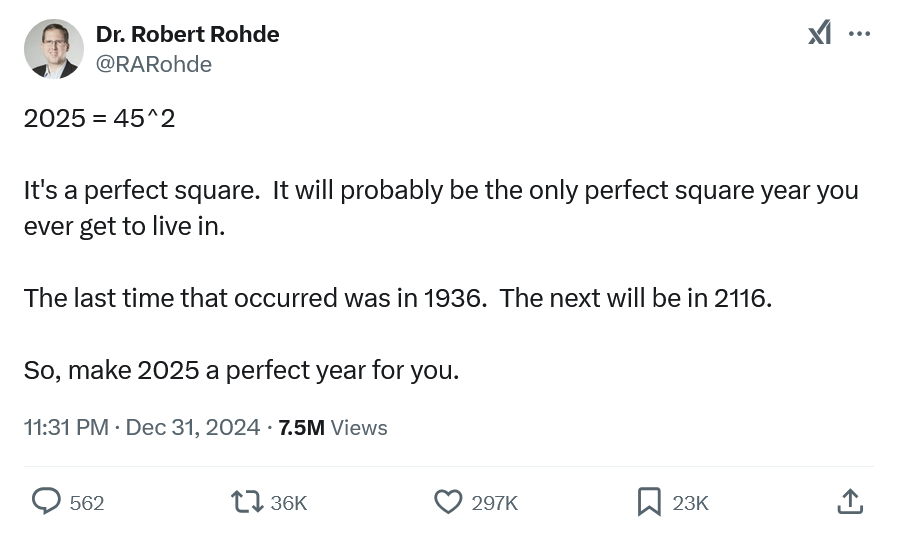

A Happy New Year to all the geeks out there:

Further reading

- A new paper in the American Economic Journal found that carbon offsets lead to a “substantial misallocation of resources”, because around half are “allocated to projects that would very likely have been built anyway”. Not that it matters, with the world to continue burning more coal than ever thanks to China.

- The North will simply outlast the South: “More than 40 percent of South Koreans below the age of forty have stopped dating. The Korea Development Institute reports that, in 2020, more than 52 percent of South Koreans in their twenties preferred a childless marriage, up from about 30 percent in 2015. More than 30 percent of all Korean households comprise only one person.”

- TSMC, the world’s leading microprocessors (chip) manufacturer, “has a fascinating origin story”. Brian Potter explains why.

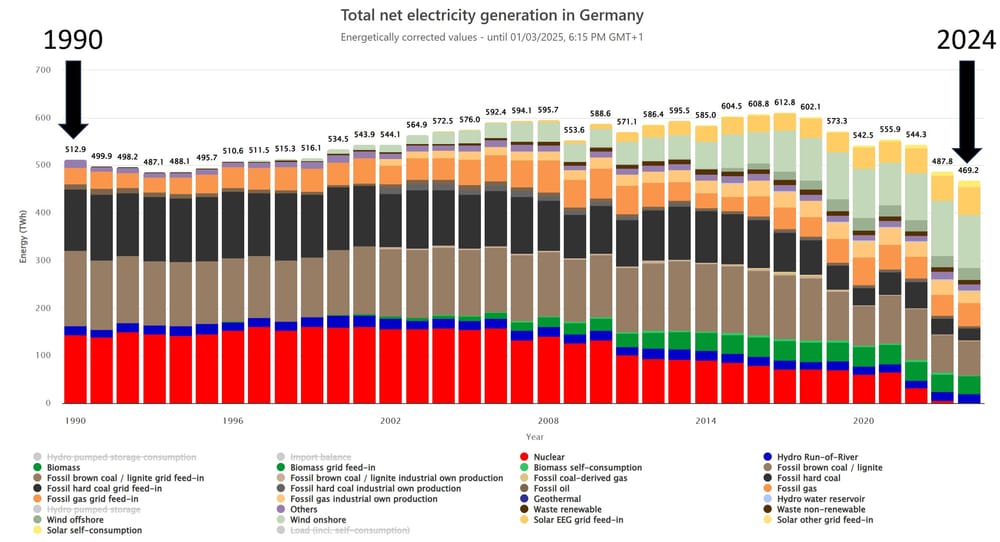

- Germany’s electricity production fell again in 2024. De-industrialisation, grid defection, or some combination?

Comments

Comments have been disabled and we're not sure if we'll ever turn them back on. If you have something you would like to contribute, please send Justin an email or hit up social media!