Gittins it wrong on inflation

The title of this post is a play on the name of the Sydney Morning Herald’s long-standing economics editor, Ross Gittins (Gettin’ and Gittins—close enough, right?). The reason I’m dedicating an entire post to him is because Gittins’ Monday column was both a personal attack and so deeply confused that I felt it deserved the full treatment, so to speak.

Anyway, on to the column. Provocatively titled If there’s no ‘price gouging’, how come interest rates are so high? – which should give you some clue as to what’s going to follow – Gittins starts with the rather bold claim that the nation’s economists have missed an obvious (to him) contradiction:

“[Y]ou can’t argue that demand has been growing stronger than supply and so causing price increases, thus justifying using higher interest rates to slow down demand, and at the same time claim there’s no evidence that profits have risen.

Sorry, guys. You can’t have it both ways. If you claim there’s been no noticeable rise in profits, you’re contradicting the Reserve Bank’s main justification for its 13 increases in the official interest rate since May 2022. (Which is funny, considering the Reserve has been prominent among those seeking to deny that profits have risen.)”

Gittins doesn’t cite a single economist making these claims. Probably because if he did, the reader would very quickly find out that the economist was only discussing profits and prices at specific points in time, or for specific industries, not how it relates to a change in the price level (i.e. inflation). He’s employing a rhetorical sleight of hand, using an appealing narrative of corporate greed with simple solutions (e.g. tax the buggers!) to explain away inflation and the need for higher interest rates.

It’s a relatively basic error: mistaking relative prices for the price level. But Gittins’ narrative tells us nothing about inflation, i.e. why the value of the currency has fallen, and continues to fall, relative to all goods and services.

Indeed, it only takes a relatively basic knowledge of economics to understand that when there’s unexpected inflation, profits for some firms will rise. That’s because firms always have a certain number of things purchased at lower prices, contracted for long periods, or borrowed before the inflation – e.g. inventories, wages, rents, loans – so there can be a temporary rise in profitability. It’s not managerial skill, or price gouging, but simply good luck – when there’s inflation, some firms’ output prices will rise faster than their input prices.

But unexpected inflation always turns into expected inflation, input prices rise, workers demand higher wages, landlords ask for more rent, and interest rates increase. The rise in profits is always illusory, and while nominal profits may well remain elevated because the price level has risen, profitability for these lucky firms will fall back to what it was before the inflation – or even below, because our government looks only at accounting profits, so higher nominal profits means more taxation.

Wading into the world of folk economics

The next several paragraphs of Gittins’ column correctly describe the standard economic view that letting prices move to higher, market-clearing levels when there are supply constraints is a good thing, not just as a means of rationing, but also because high prices incentivise new supply.

That doesn’t necessarily mean new production (which is all Gittins mentions); it could be as simple as sending bottled water from City A to City B to another after City B was hit with a natural disaster. Without higher prices creating the incentive to truck them to the affected city, those bottles of water would stay put and everyone is worse off.

So, Gittins knows why economists dislike price controls. He also appears to understand why central banks tightened monetary policy:

“This dual, supply caused and demand-caused, explanation for inflation fits well with the Reserve’s analysis of the origins of the great surge in prices – in all the developed economies – in late 2021 and 2022.

Part of it was from disruptions to supply caused mainly by the COVID-19 pandemic, but also the Ukraine war, which pushed up the cost of building materials, various manufactured goods, shipping and oil and gas. But part of it was caused by the excessive stimulus applied to the economy by governments and central banks during the pandemic and its lockdowns, which had caused the demand for goods and services to run ahead of the economy’s ability to produce them.

Increasing interest rates can do nothing to increase supply, and the end of the lockdowns would see supply gradually return to normal, the Reserve reasoned. But higher rates could dampen the excess demand caused by all the extra government spending and rock-bottom interest rates that was applied to ensure the lockdowns didn’t lead to a lasting recession.

Yes, monetary policy works by influencing aggregate demand – nominal GDP. It’s a blunt tool but in an indebted country like Australia, higher interest rates reduce total household disposable income while also indirectly tightening fiscal policy through bracket creep. Put it all together and it takes the heat out of aggregate demand by slowing down the growth of money, assuming the government doesn’t give it back or spend it all ( whoops!).

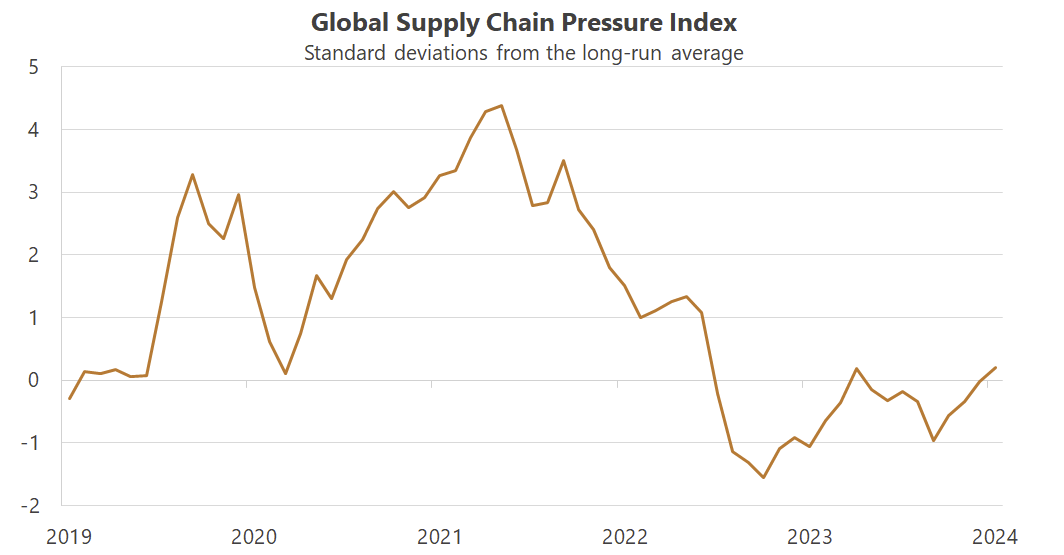

Gittins is also correct that monetary policy can’t fix supply issues. The good news is that global supply chains are back to normal, and have been since February 2023:

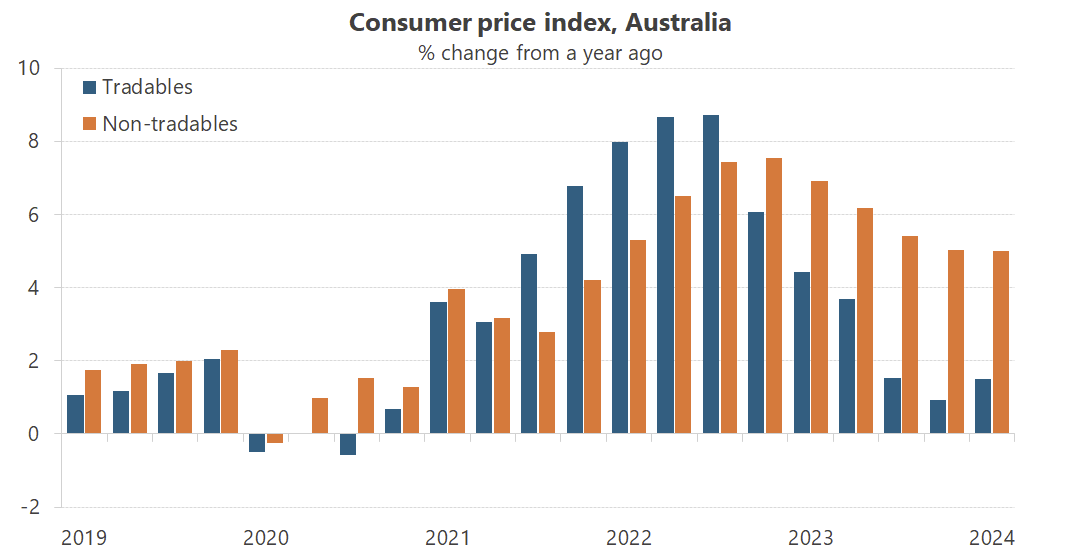

That’s probably also why the non-tradables component, i.e. domestically-driven inflation, is now the main driver of growth in the consumer price index:

But it’s not long before Gittins again wades off into the world of folk economics:

“See how this analysis is undermined by claims there’s no sign of firms earning higher profits in the post-pandemic period? It implies that there’s no sign of excess demand, suggesting the surge in prices must have come only from supply disruptions and other cost increases.

In which case, the justification for maintaining high interest rates is greatly weakened. It implies that demand hasn’t been growing excessively and, rather than waiting for the supply problems to resolve themselves, we’re going to batter down demand to fit.”

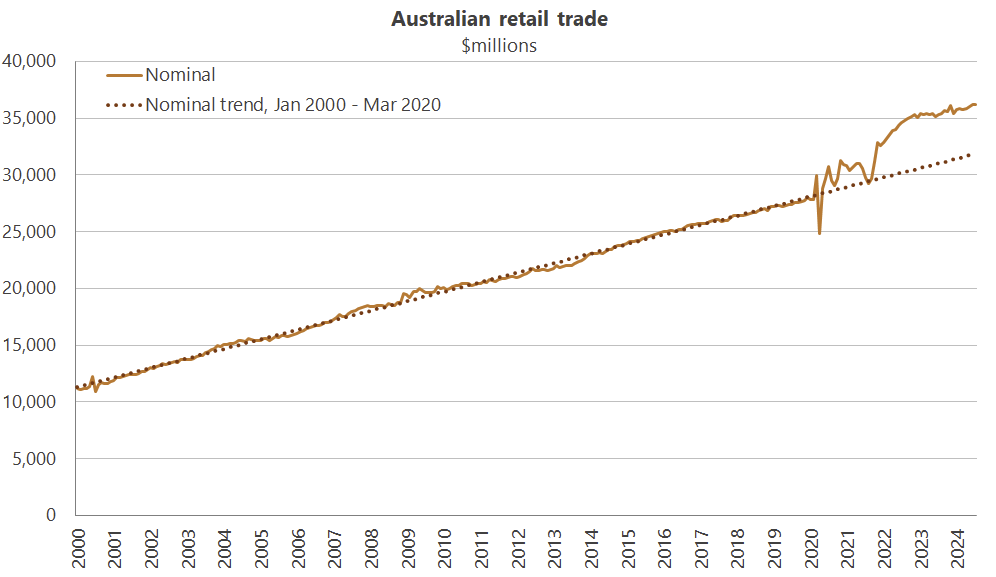

It does nothing of the sort. While profits may rise temporarily during periods of excess demand, they do not directly cause inflation, and profits and inflation rising together says nothing about causation. In fact, because supply disruptions and “other cost increases” (whatever that means) have now eased, today’s inflation is almost entirely caused by excess demand – an increase in nominal spending – so the justification for maintaining high interest rates is greatly strengthened. Just look at retail sales:

Overly stimulatory demand-side fiscal and monetary policy is what caused both profits and inflation to increase in tandem. Honestly, I’m not sure how Gittins can look at the evidence in front of him and conclude the opposite.

Perhaps he just isn’t looking.

But wait, there’s more

Gittins concludes by asking:

“Why so many economists want us to believe that, despite decades of increased market concentration – more industries dominated by just a few huge firms – and despite excessive monetary and budgetary stimulus, profits never increase, I’m blowed if I know.”

I’m all for increasing competition, as is every other economist I know. But an increase in market concentration doesn’t mean competition has fallen. The two often go together, but they’re not actually related; a competitive market can even lead to more concentration due to the benefits of things like economies of scale and network effects that allow big firms to be more productive. Indeed, you can have perfect competition with just two firms (the Bertrand model).

As economists writing in well-regarded journals point out, “concentration is worse than just a noisy barometer of market power. Instead, we cannot even generally know which way the barometer is oriented”.

The relationship between concentration and competition (i.e. market power, which is what we actually care about) is especially weak in a country such as Australia, given our relatively small, spread-out population. Take our supermarkets:

“The fact is Coles and Woolworths (‘Colesworth’), while dominating the domestic market with around a 60% share (a figure that excludes growing competitors such as Amazon), are not very profitable businesses. Their net profit margins have been constant at around 2.6% over the past few years, which is hardly indicative of price gouging or ‘greedflation’. Australia’s supermarkets actually have a lower return on investment than their overseas peers, in part because Australia is a big country, sparsely populated, relatively small by global standards, requires plenty of ongoing investment to keep shelves full and customers happy, and is therefore a more expensive place for a supermarket to do business.”

Industry concentration tells us nothing about level of market competition. But even if it did, it matters where the concentration is happening. A 2019 report by the Office of the Chief Economist found that most of the rise in Australian market concentration between 2002 to 2016 happened in export-focused industries that were already highly concentrated, largely due to improved productivity, with no increase in most other industries.

That’s good news!

Of course, rising concentration in already concentrated industries may come with its own set of problems unrelated to market power, although probably not where Gittins thinks: the report worried that these large firms would “use their size advantage to bend the rules and gain advantage through influencing the political process… lobbying is increasingly becoming the preferred strategy”.

A Future Made in Australia subsidies, anyone?

Comments

Comments have been disabled and we're not sure if we'll ever turn them back on. If you have something you would like to contribute, please send Justin an email or hit up social media!