High interest rates are here to stay

I’m taking a break from writing about energy and US politics this week because I think it’s time to take another look at the Australian macro situation. That means more about inflation, which in my view is still the issue today. It’s especially relevant considering that last week, the US Fed, UK’s Bank of England, and Sweden’s Riksbank all cut rates.

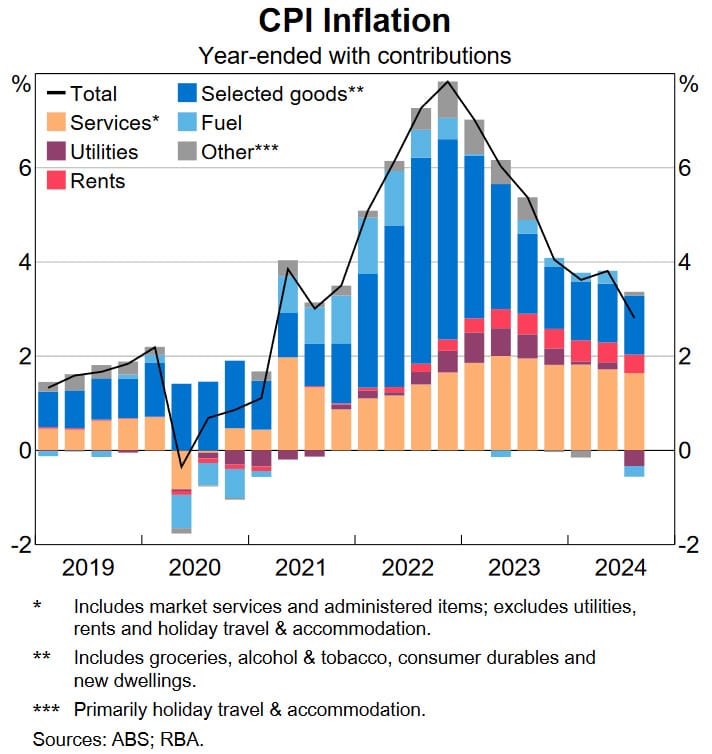

Unfortunately for those with a mortgage, the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) recently explained that it’s not expecting “inflation returning sustainably to the midpoint of the target until 2026”, and that it’s going to ignore the headline figure because of the government’s “cost of living” meddling.

So, no rate cuts here for some time:

“Headline inflation was 2.8 per cent over the year to the September quarter, down from 3.8 per cent over the year to the June quarter. This was as expected due to declines in fuel and electricity prices in the September quarter. But part of this decline reflects temporary cost of living relief. Abstracting from these effects, underlying inflation (as represented by the trimmed mean) was 3.5 per cent over the year to the September quarter.”

Following Donald Trump’s election in the US, market pricing moved from a 62% chance of a rate cut at the February meeting to no cut until at least May. That’s because Trump’s policies are likely to raise real interest rates, with spill-over effects for Australia potentially even pushing a cut back as far as August.

In that context, I think it’s sensible that the RBA is talking down the prospects of a rate cut. Central banks have a tendency to move too late and when they do, to go too small. That’s because they’re relatively risk averse, and wouldn’t dare make a move if there was a chance that they’d have to reverse course later.

That means they tend to stay put for longer than they should, because no decision is better than a wrong decision, at least in terms of their career prospects. Remember Philip Lowe?

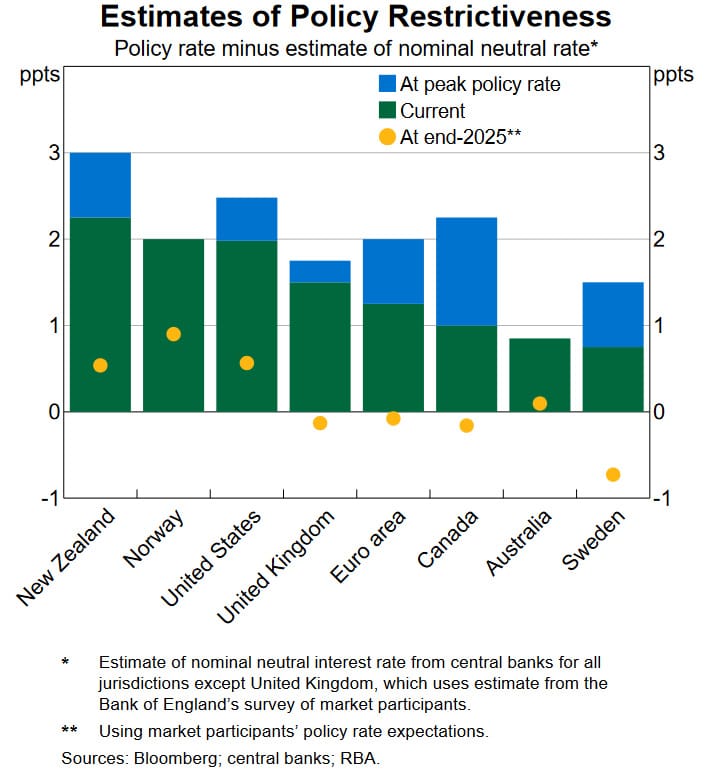

But the RBA doesn’t have much of a choice this time, either. One of the last advanced-economy central banks to act on inflation, the RBA also had one of the more timid responses. Even with most central banks having cut their cash rates multiple times, Australia’s estimated policy restrictiveness is only above Sweden:

This is a crucial measure that many pundits miss because they don’t understand how monetary policy works. That wall of shame includes at least two names: former Labor politician Craig Emerson, who seemingly doesn’t understand that monetary policy is a nominal phenomenon and that it’s perfectly possible to have too-loose monetary policy and a weak economy being decimated by real factors (hello, 1970s and 80s); and economic commentator Stephen Koukoulas, who has been calling for 100 basis points worth of cuts this year on a technicality.

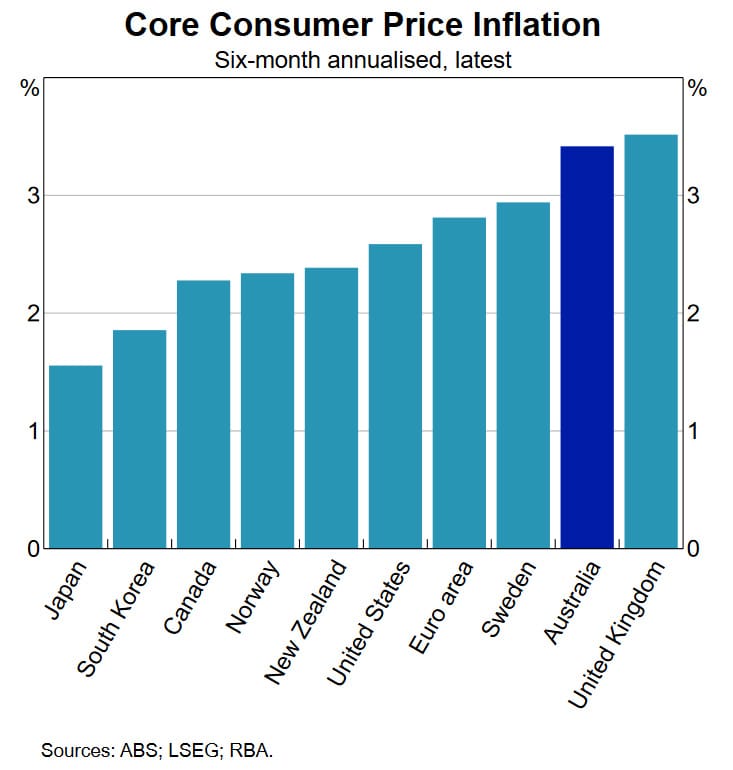

Thankfully, the RBA is ’looking past’ the distortions that Koukoulas wants it to ignore and is focused on core inflation, which strips out “volatile” components like food and energy. In Australia, core inflation is still running well ahead of other countries that have more restrictive monetary policies:

The RBA isn’t belittling people when it strips out two things they care a lot about, like food and energy. It’s just trying to get a read on inflation so that it can determine whether its current policy position is appropriate or not. Removing volatile items, especially when one of them is being actively manipulated by the government, helps it do that.

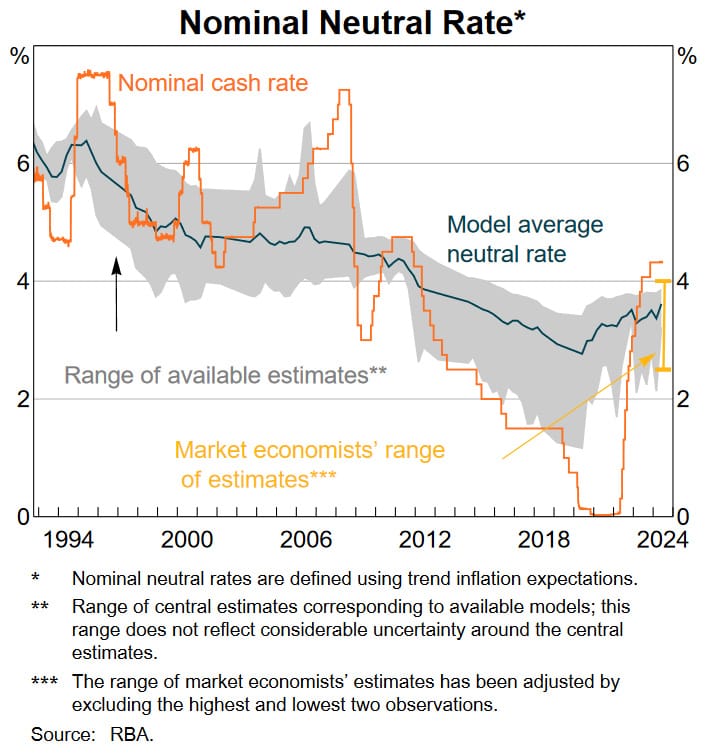

I also think it’s important to clarify that the cash rate is not a good indicator of how loose or tight monetary policy is; if it was, Argentina – where the benchmark interest rate is 35% – would have some of the tightest money in the world right now. Yet annual inflation is running at 209%.

What matters for monetary policy is what the central bank’s cash rate is relative to the unknowable neutral rate. It’s an educated guess, but the RBA thinks that its cash rate target is currently ever-so-slightly above that rate (and was wildly below it from 2020-22, hence the subsequent inflationary surge):

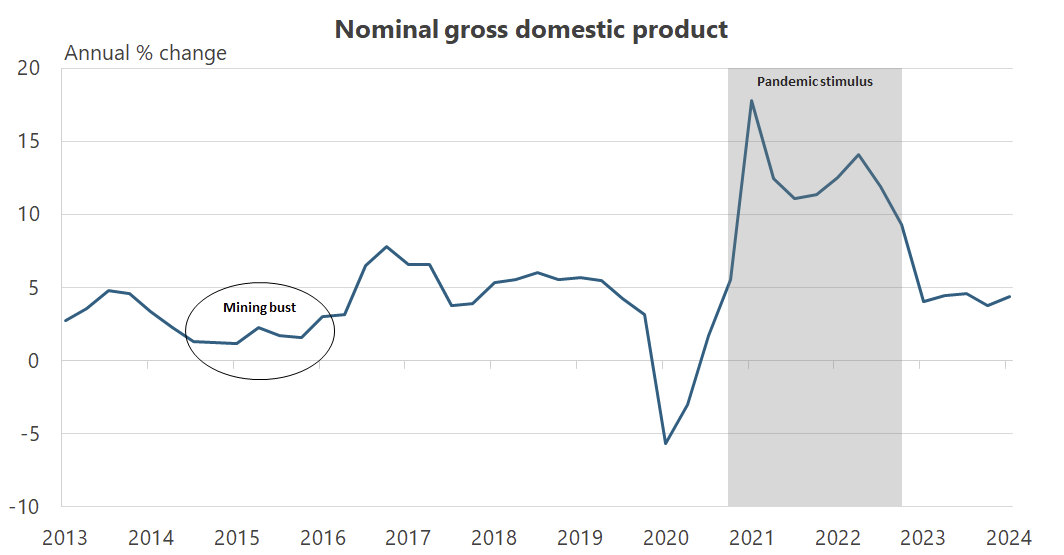

Another indicator for the stance of monetary policy is nominal GDP. It’s less reliable in Australia than in more diversified economies such as the US, mostly because of the large impact changes in global commodity prices can have here, but it can still tell us something. We don’t yet have the September quarter national accounts, but nominal GDP growth appears to have stabilised at a rate consistent with 2-3% inflation in the past:

The problem is we’re in the present, not the past; and the Australian economy is barely growing at all. If it persists in keeping aggregate demand (nominal GDP growth) stable to preserve employment in a low-growth environment, the RBA is going to have to tolerate higher inflation for longer.

If it takes its foot off the brake and eases further, nominal GDP growth could start ratcheting back up, raising the prospect of an inflationary rebound and even higher interest rates in the future unless something happens to trigger a burst of real GDP growth.

The economy is misfiring

The Australian economy is in trouble, but its problems are real, not nominal. While monetary policy can influence real variables – e.g. if it’s too tight, it can reduce real output – it can’t target them. In the long run, monetary policy can’t do anything to sustainably raise employment, or change the real interest rate.

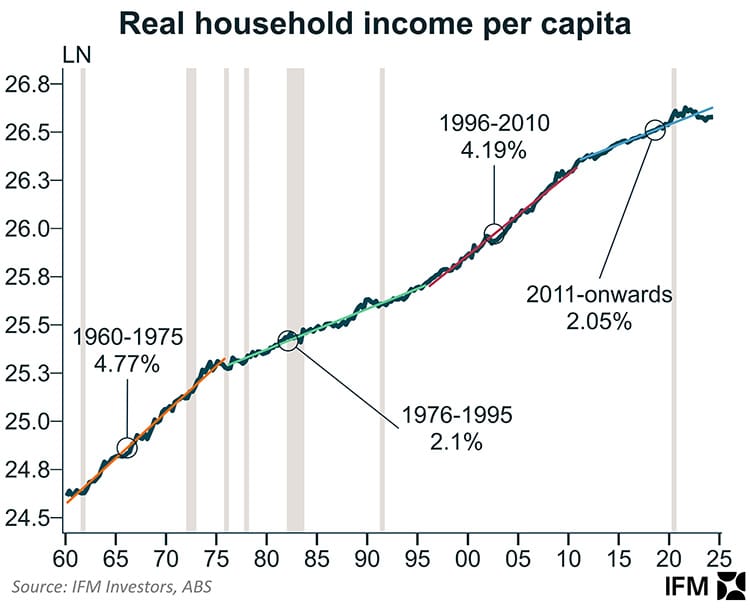

IFM’s Alex Joiner recently tweeted about the recent slowdown in real per capita incomes, noting that the current trend is low compared to the 1990s productivity boom and naughties mining booms (thanks, China!) but is pretty much in-line with the mid-70s to the mid-90s:

The potential growth of the Australian economy has fallen because our politicians have done very little reform since the late 80s, which is key to boosting productivity and improving real variables, such as incomes, in the long run.

There’s only one thing propping up the economy right now: debt-financed spending by our state and federal governments. As the RBA noted:

“Around three-quarters of employment growth over the past year was in the non-market parts of the economy such as health and social care, where labour demand tends to be less cyclical and often more aligned with government spending.”

Or in chart form:

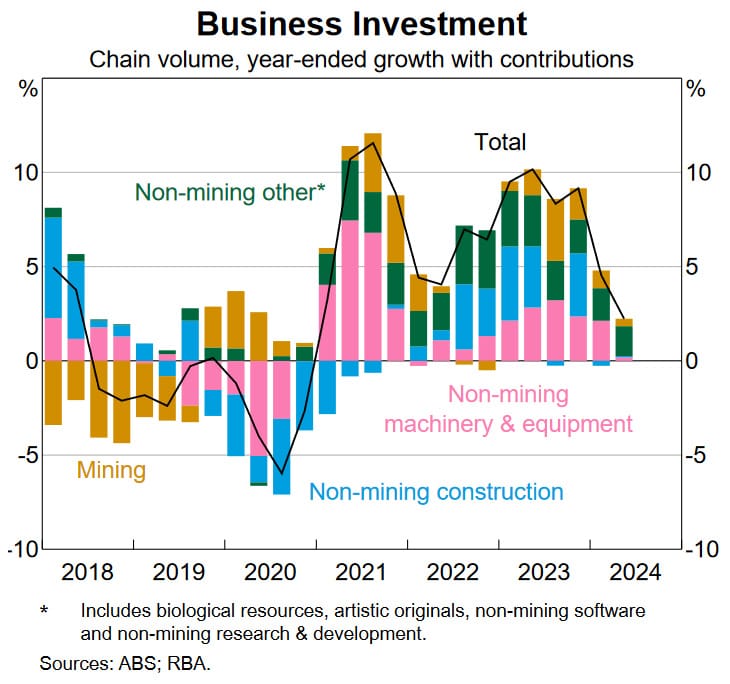

It’s probably safe to assume that without such spending and the post-lockdown migration rebound, Australia would already be in a deep, stagflationary recession. And the outlook isn’t great, with business investment growth – a key indicator of future productivity – slowing considerably:

Inflation should be the RBA’s only priority

Economic policy is about trade-offs. The government and RBA prioritised employment over all else during the pandemic, and the result was the largest surge of inflation the country has seen since the 1970s.

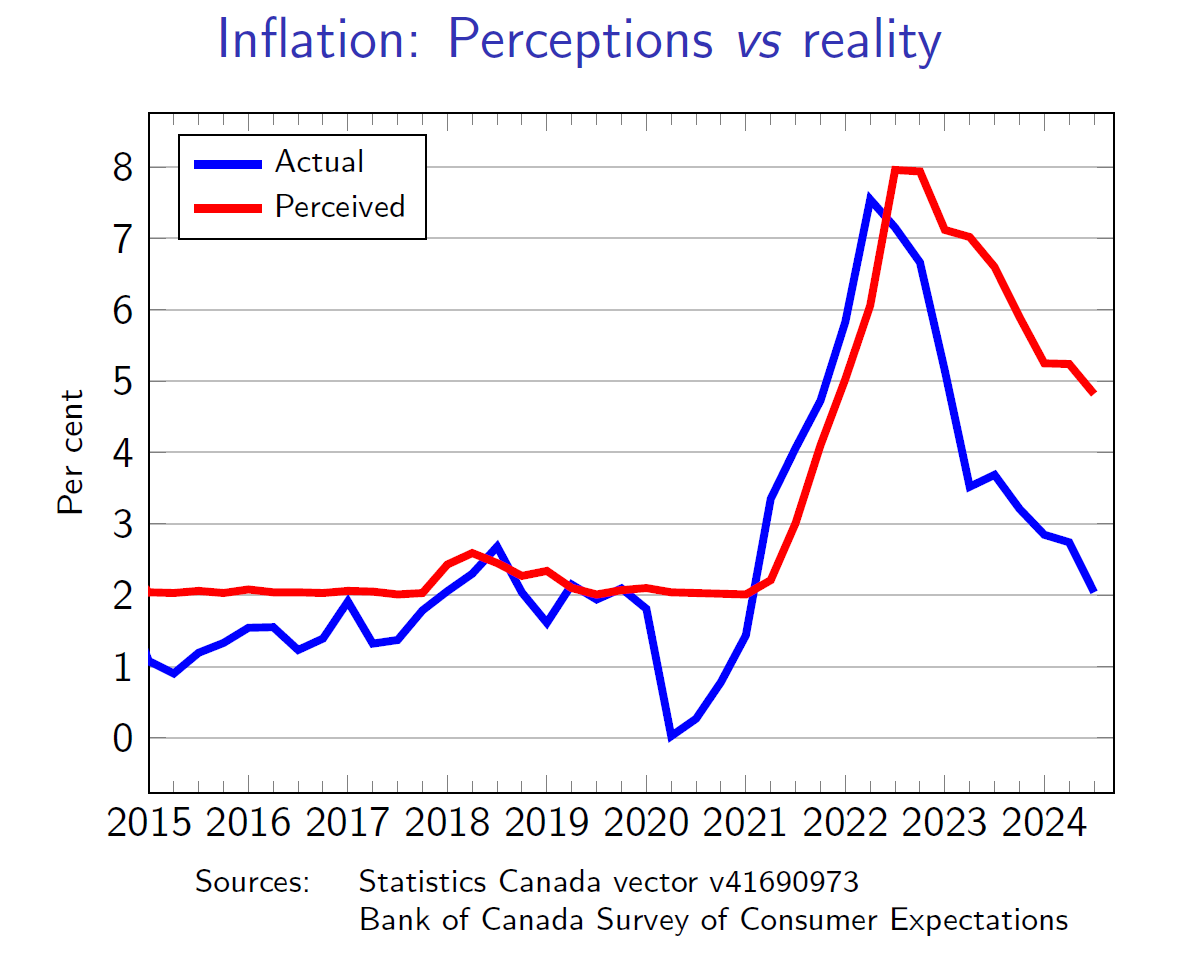

Expectations matter for monetary policy. If the RBA is perceived as being too dovish, or not committed to returning inflation to something approximating its 2.5% midpoint, people’s behaviour will change and it gets all the more difficult to bring inflation down. Recent research from the Bank of Canada found that people ‘feel’ inflation even after it has started to ease, which is perhaps one reason for the ’long and variable lags’ that are associated with monetary policy:

Treasurer Chalmers might claim that the RBA is “suffocating” the economy, but it’s really our governments who are doing that. Tax collections as a share of GDP are at record highs, and the composition of that tax take is getting worse because it’s increasingly disincentivising productive work: Treasury projects that income taxes will grow from 52 to 58% of the overall tax base by 2060.

Government spending – also at a record high share of GDP – is crowding out the market sector, the only real source of productivity growth in this country but whose share of total jobs is at a record low.

Tellingly, RBA Governor Bullock last week said that:

“My reading — when I speak privately to the Treasurer and when I hear him speak on television and radio — is that he’s fully aware of the inflationary implications of his own policies.”

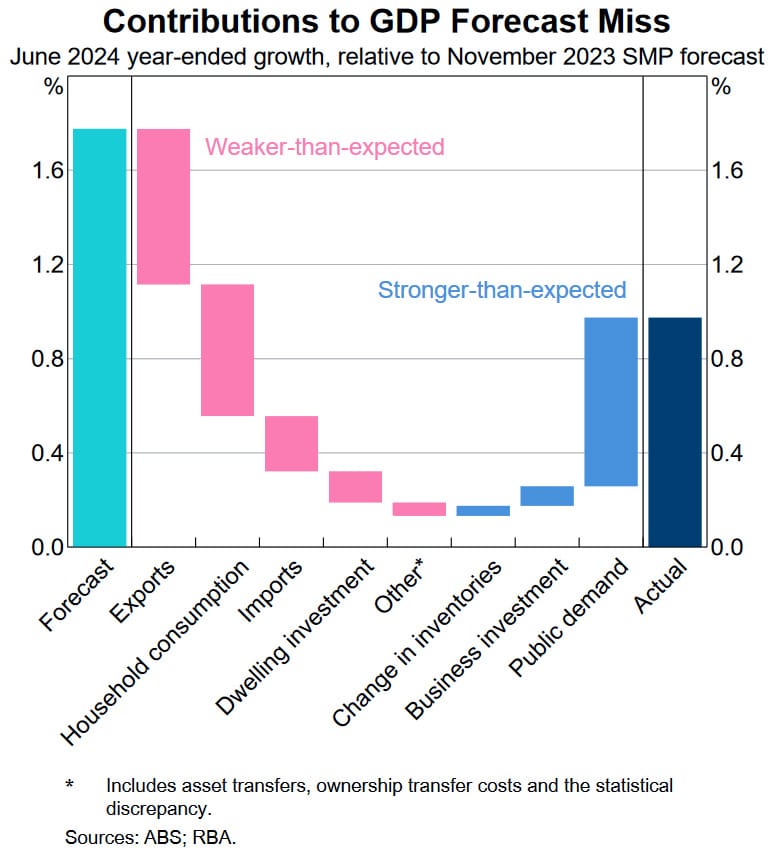

Bullock has a point. All levels of government have ignored the Governor’s warnings, spending considerably more than the RBA expected:

That’s because politicians have to play politics. We all saw the playbook that Queensland Labor (and to a lesser extent, the Liberals) was calling from during its recent state election: a cash splash like we’ve almost never seen before. As Bullock lamented:

“It’s not just the federal government, it’s the state governments as well. The fact that we’ve had to revise up our public demand forecasts, it’s reflected the fact that there’s been more announcements and more things going on.”

In the US, both Trump and Kamala Harris also pledged to spend like drunken sailors. Debt? Who cares; that’s someone else’s problem!

As the next federal election draws near, I fully expect the Albanese government to call many of the same plays. Cost of living relief will be extended, and many populist policies and gimmicks will be embraced if they’re likely to be supported by those in marginal seats, even if they would do more harm than good and delay the return to price stability.

Remember, this is a federal government that will have been shaken to its core by the Democrats’ loss in the US – many of its policies were ripped straight from the Biden administration – and if the HECS debt forgiveness is any indication, looks as though it will become increasingly unhinged as May 2025 approaches.

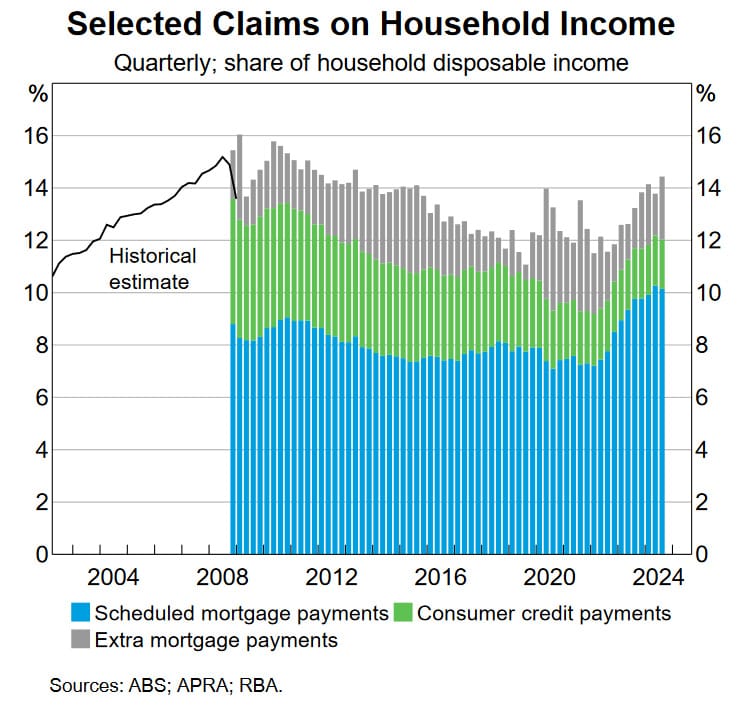

The good news is that while Australia might already be condemned to a stagflationary recession, a debt crisis looks unlikely. New loan commitments are still growing, which wouldn’t be the case if monetary policy was excessively tight. And while the share of household income going to servicing their debts has risen, it’s still below where it was prior to the Great Recession, suggesting households are handling themselves just fine:

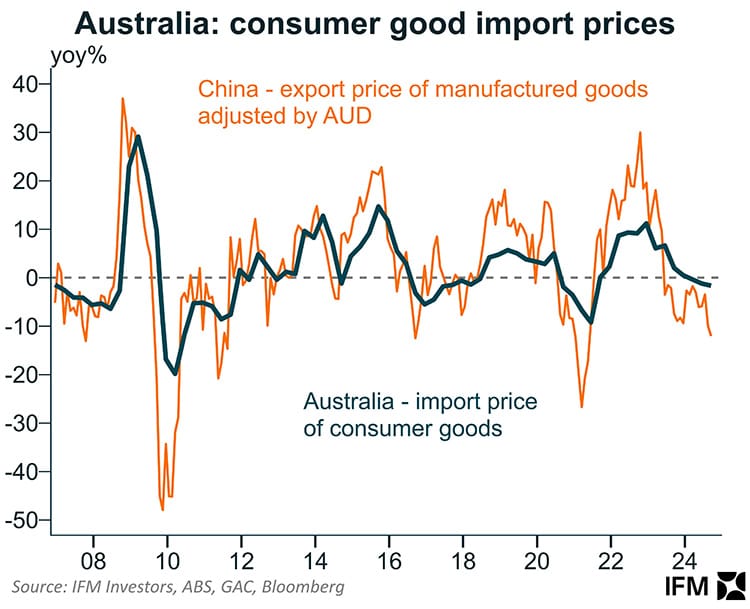

China is also exporting disinflation to Australia once again, which is certainly handy:

It’s basically an unearned positive productivity shock, and might be the only thing that brings inflation down to within the 2-3% target given the RBA’s relatively loose monetary policy, which is no doubt helping to keep services inflation sticky:

The only point I’ll concede to the dovish commentators I named and shamed above is that inflation doesn’t hit the economy in a uniform manner. People really dislike inflation because it has large welfare costs for households, and the relative price changes that happen during the inflation have affected everyone differently.

For example, young people have “had to dip into their savings to meet higher rent and mortgage repayments”, while older Australians – many of whom have already paid off their homes – have enjoyed record-high equity prices and positive yields on their cash savings.

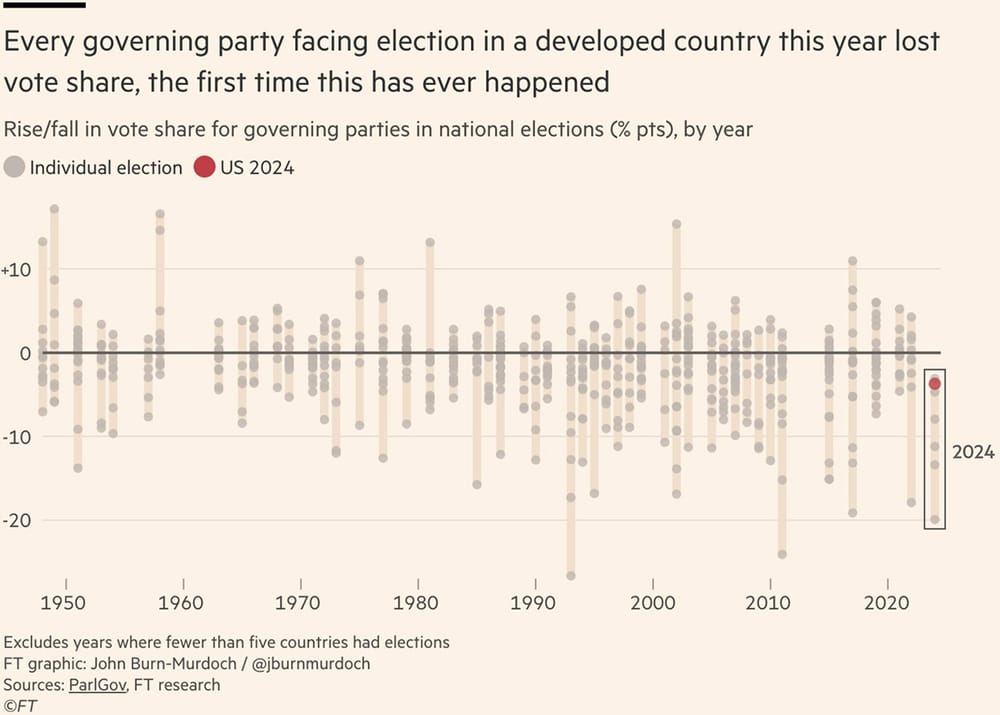

It also tends to “disproportionately hurt the poor and are associated with reductions in trust in government”. It shouldn’t come as a surprise that all the inflation-incumbents have been struggling in recent elections:

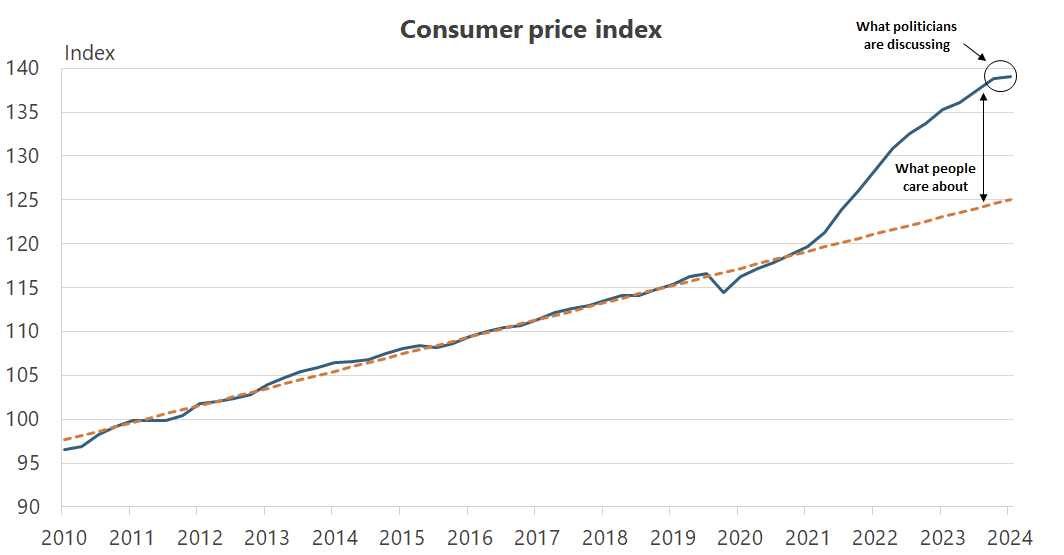

Politicians should be aware that the COVID-19 stimulus created a large, one-time shock to the price level. That’s what the average punter is annoyed by; that it now costs $14 instead of $10 for a pint, not that it will increase by another 60c next year instead of the usual 30c.

The only true fix is to get real growth and real wages moving again, so that incomes can claw back some of the purchasing power that has been lost. Temporary cash handouts dressed as “cost of living support” won’t do anything to change the fact that for many, they have just experienced a permanent real wealth shock. Unless that fact is acknowledged and a plausible solution offered, then they’ll be looking for someone to punish at the ballot box come May 2025.

Comments

Comments have been disabled and we're not sure if we'll ever turn them back on. If you have something you would like to contribute, please send Justin an email or hit up social media!