A hawkish cut

Well, it finally happened. For the first time since November 2020, the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) cut its overnight cash rate, from 4.35% to 4.10%.

Here’s the key part of Governor Bullock’s explanation:

“The Board’s assessment is that monetary policy has been restrictive and will remain so after this reduction in the cash rate. Some of the upside risks to inflation appear to have eased and there are signs that disinflation might be occurring a little more quickly than earlier expected. There are nevertheless risks on both sides.

The forecasts published today suggest that, if monetary policy is eased too much too soon, disinflation could stall, and inflation would settle above the midpoint of the target range. In removing a little of the policy restrictiveness in its decision today, the Board acknowledges that progress has been made but is cautious about the outlook.”

While a long time coming, this decision was largely expected before the RBA even met: the last consumer price index update was softer than most anticipated, and the implied odds based on financial market futures pricing (a proxy for expectations) in the lead up suggested there was a 90% chance of a 25 basis point cut.

This shouldn’t be the first of many

Futures markets price what the RBA is likely to do, not what it should do. There has been a huge amount of political and media pressure placed on the RBA for several months now, and I suspect that the criticism it would have faced by not cutting has forced its hand here – hence the “hawkish cut”.

So, the Governor was right to be “cautious on [the] prospects for further policy easing”, as it’s not at all clear that even this cut was needed. That’s because from a purely economic point of view, the Australian economy – despite its lacklustre real growth – does not appear to have a nominal demand problem.

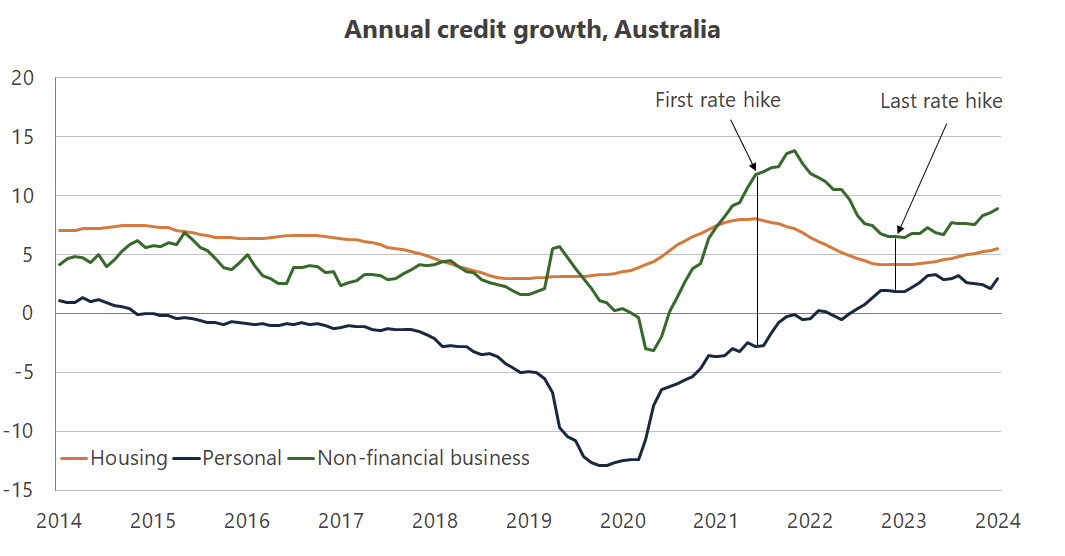

For example, credit growth to all borrowers has been steadily increasing since the end of 2023, which was around when the RBA did its last rate hike (8 November 2023).

Rather than in desperate need of lower rates to boost activity, the Australian economy looks as though it’s receiving ample liquidity. If anything, the rebound in the demand for investment (borrowing) may have been pushing real interest rates up.

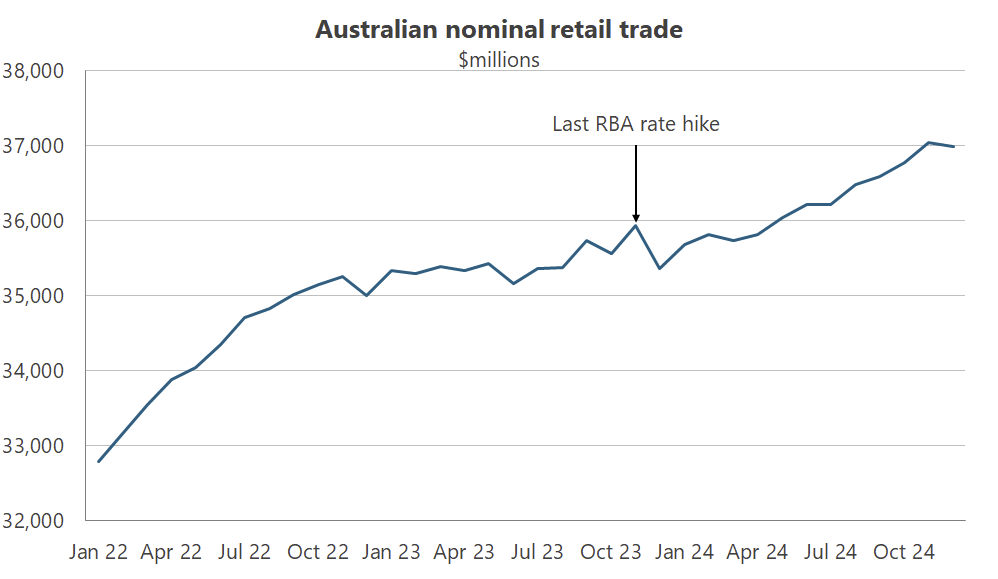

A similar pattern can be observed in retail sales, which after plateauing for several months during the RBA’s tightening cycle, have proven to be robust.

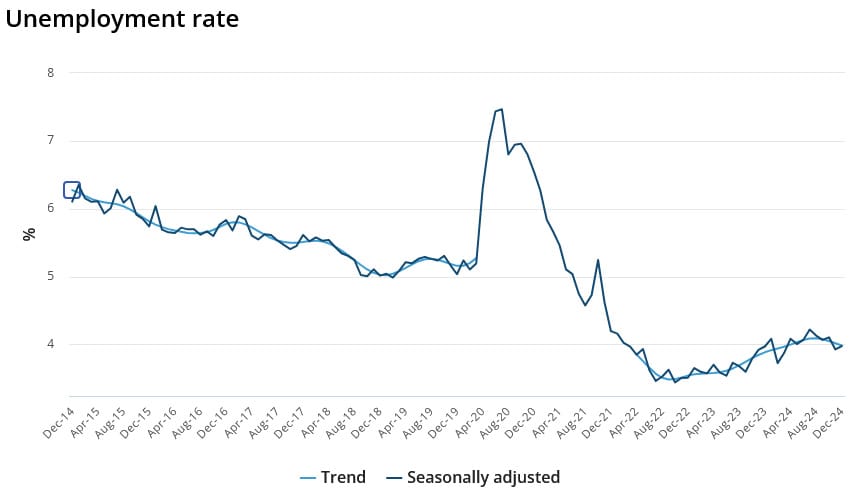

Then there’s the labour market, which – as with lending and retail sales – has been heating up for the past six months.

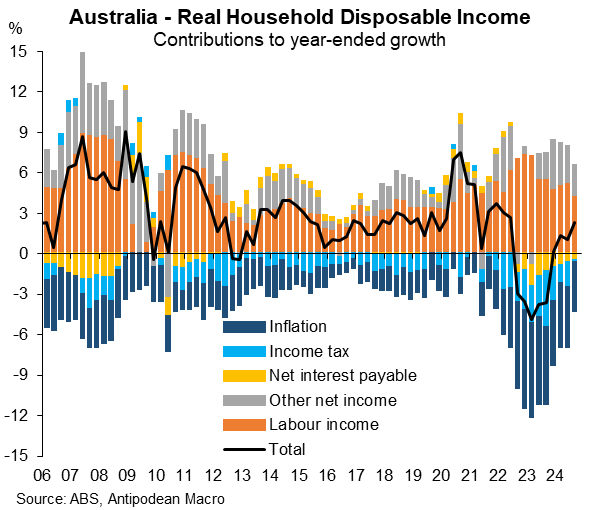

As for whether households even need a rate cut to help with the cost of living, interest payments really aren’t what’s stressing their budgets, either; inflation is!

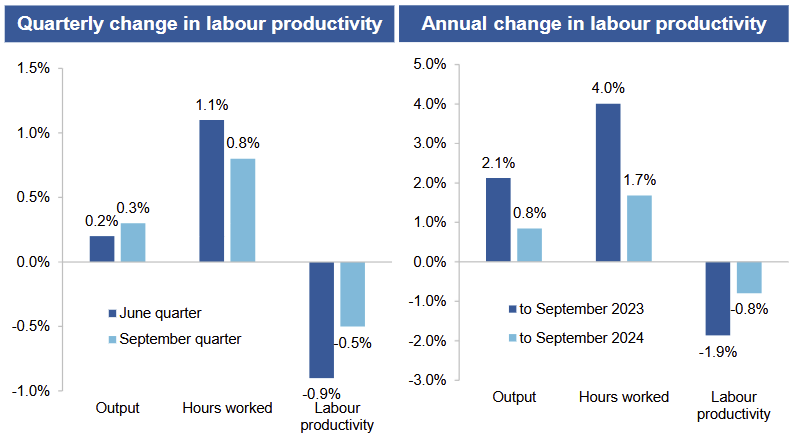

Then there’s the problem of wages. Australia has experienced zero productivity growth for some time, and no level of government has tried very hard to change that unfortunate fact.

If you have no productivity growth, then to achieve the RBA’s mandate of 2-3% inflation, nominal wages – currently growing at 3.5% annually – must be kept within the same range (i.e. zero real wage growth). Any growth in nominal wages above and beyond that rate will only translate into higher prices.

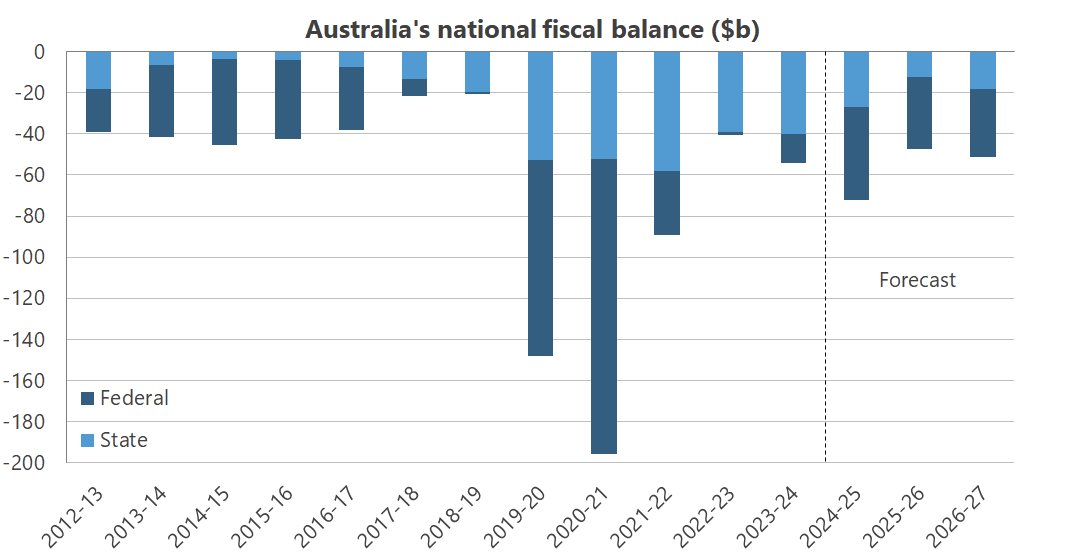

Finally, substantial ongoing fiscal deficits may require a steady or higher cash rate rather than cuts. Deficit spending without a credible plan to pay back the debt generates inflation, and eventually interest rates have to follow.

This is the current PBO forecast (October 2024), which was flattered by high commodity prices, inflationary-driven bracket creep boosting revenue, and taking the government at its word that it would only increase expenditure by 2.8% a year from 2025-26, after the huge 5.7% real spending increase in 2024-25 (which doesn’t include any election commitments).

None of these data suggest that a rate cut was needed.

Indeed, if there’s one overarching reason why the federal election will be held before the May deadline, it’s because Albanese and Chalmers won’t want to present another Budget or wait for another RBA meeting, which are currently pencilled in for 25 March and 1 April, respectively:

“The Government has committed tens of billions of dollars in ongoing spending using a river of gold that has stopped flowing.

…

A new Budget means a new set of forecasts that would reveal all this in flashing lights. Iron ore prices and inflation are a bandaid that has been covering up the Government’s fiscal mismanagement, and a Budget means they’d have to rip it off and reveal their surpluses were a temporary fluke.”

That puts the most likely date for the federal election on 29 March, a date that both rules out another Budget and conveniently falls before the RBA’s next meeting. For that to happen, an election would have to be called by 24 February.

A warning from America

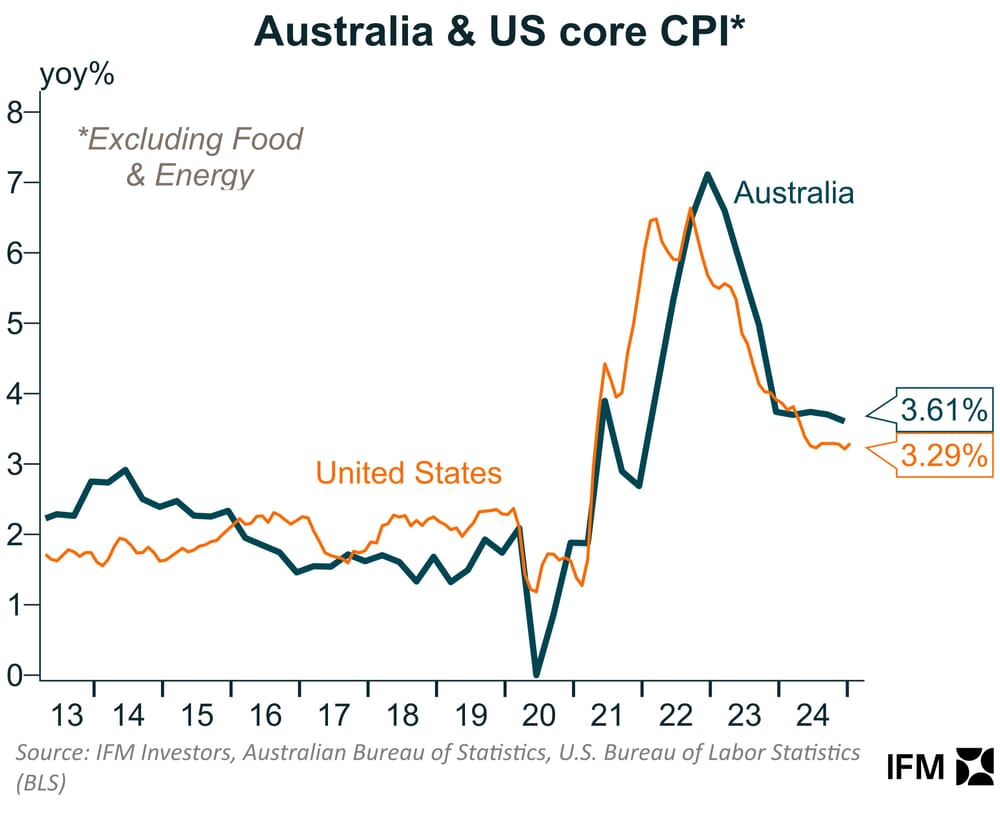

Those who keep track of monetary policy will know that the US Federal Reserve cut rates three times last year, only for inflation to jump back up from 2.4% to 3% – its highest rate for six months.

That’s an outcome that the RBA will want to avoid.

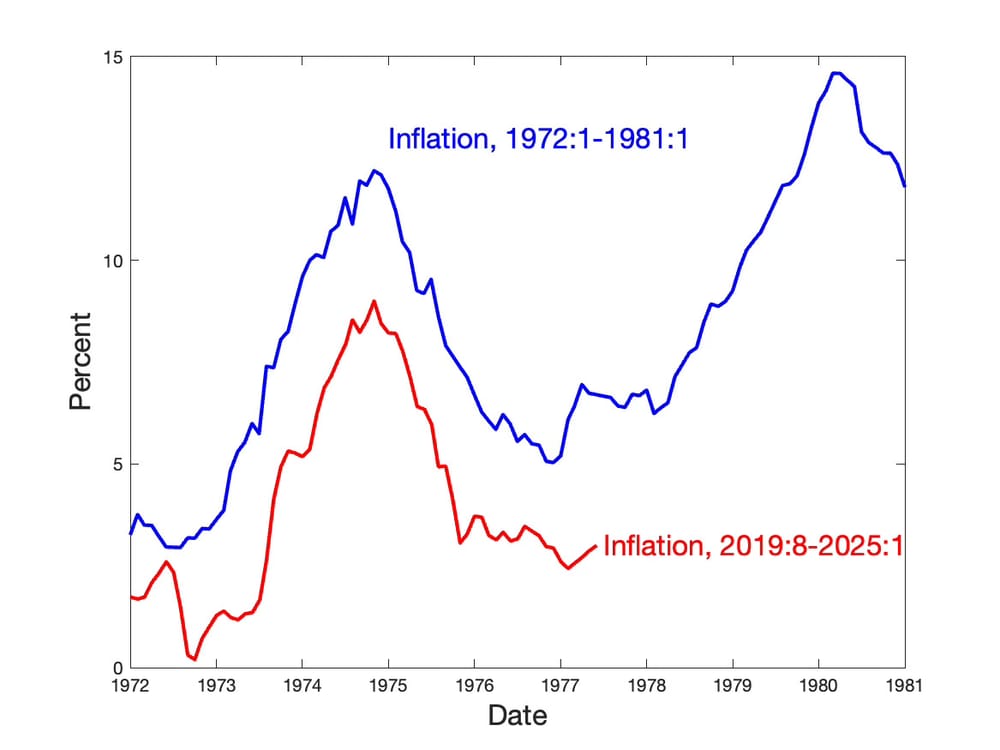

As economist John Cochrane recently described it, “inflation is like cockroaches. When there are only a few left and you’re on a downward glide path is not the time to let up”.

He also offered this chart – plotted “for fun, not as a forecast”, given correlations alone tell us little about causation or future paths – showing an uncomfortable similarity between today and the last major inflationary shock.

Today’s 25 basis point cut is not likely to be consequential, especially when paired with the hawkish statement that will hopefully keep expectations in check.

But if the RBA gets complacent, inflation could very well come back with a vengeance, as it has done many times throughout history. And that’s an outcome the RBA – already lacking in credibility after the whole Philip Lowe saga – should desperately try to avoid.

Comments

Comments have been disabled and we're not sure if we'll ever turn them back on. If you have something you would like to contribute, please send Justin an email or hit up social media!