November's inflation and the RBA's dilemma

Australia’s monthly inflation figures for November were released this morning, providing some insight into the all-important December quarterly figures and what the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) might be thinking ahead of its 17–18 February meeting.

I say some for a few reasons. First, the ABS hasn’t (yet) fully resourced its monthly consumer price index (CPI) indicator. This release only includes updates for 77% of prices in the basket, and only 48% of them are monthly (the rest being annual or quarterly collections).

Second, Black Friday came late in November this year, which could affect the Bureau’s seasonal adjustment.

Third, a hodgepodge of federal and state electricity rebates have distorted the headline figure, as has the rebound from various low income and first home buyer assistance packages that suppressed housing costs in October.

Breaking it down

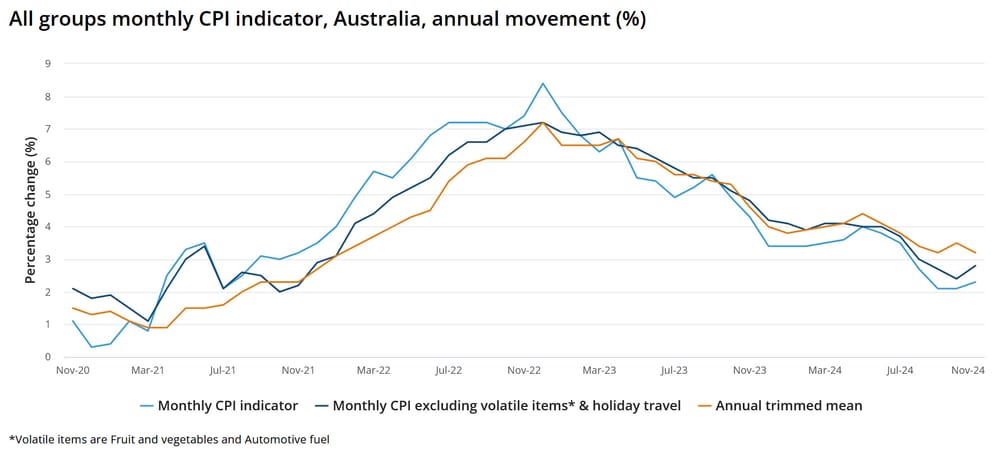

Monthly CPI increased to 2.3% in the year to November from 2.1% in October. Meanwhile, the trimmed mean measure fell to 3.2% from 3.5%.

Still too hot for the RBA but certainly getting closer. Here’s the ABS:

“Annual CPI inflation has risen since last month, in part due to the timing of electricity rebates. In some states and territories, households received two rebate payments in October in lieu of not receiving a payment in July. From November most households received one payment. As a result, electricity prices fell 21.5 per cent in the 12 months to November, compared to a fall of 35.6 per cent to October.

When prices for some items change significantly, measures of underlying inflation (like the annual trimmed mean and CPI excluding volatile items and holiday travel) can give more insights into how inflation is trending.

Annual trimmed mean inflation remains higher than CPI inflation as it removed large price falls for electricity and automotive fuel.”

Removing electricity and fuel is problematic – they’re important to people! – but the ABS is correct: it’s precisely because those items are volatile that a large price spike – up or down – means they can predictably be expected to move just as much in the other direction in the future. Removing them leaves only the most ‘stable’ 70% of prices, which are a better forecast of future inflation, which is what we care about.

But even with the slight trimmed-mean cooling in November, I’m not sure it will be enough for the RBA to cut in February.

What other indicators are saying

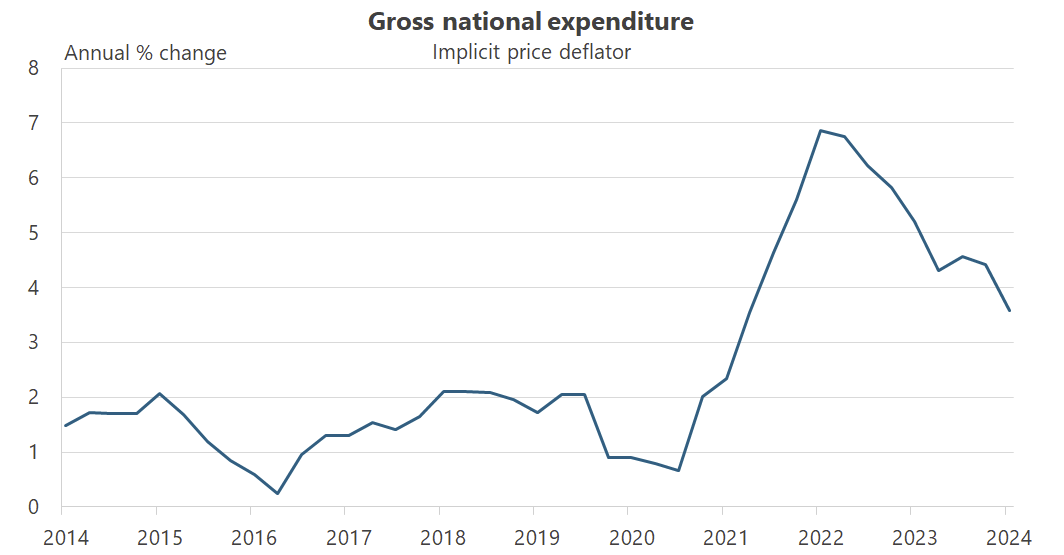

My preferred measure of demand, the Gross National Expenditure Implicit Price Deflator, has slowed but is still growing at 3.6%, suggesting the RBA still has work to do.

Unfortunately it’s a lagged indicator; the most recent data point is from the September quarter (i.e. July-Sept 2024 data).

A more up-to-date indicator is the RBA’s favourite, the unobservable and elusive NAIRU, or non-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment. I don’t put all that much weight on it, because I believe that it gets the causation backwards: its key assumption is that strong employment growth causes inflation, without first considering whether the employment growth itself was caused by a change in supply or demand.

But even by its own estimates, the RBA’s NAIRU suggests that the current cash rate is about 30 basis points too low.

Another indicator is what other countries are doing. The RBA decided to walk the “narrow path”, keeping rates much lower than in other advanced economies. So while the likes of Canada (3.25%) and New Zealand (4.25%) now have policy rates below Australia (4.35%), inflation in both countries has already fallen to around 2%. While that’s certainly positive for the outlook, it could take several months longer in Australia given the different approaches.

But a lot could change

There are also forces working against a cut, such as the recent fall in the Aussie dollar that could put pressure on rates to stay higher for longer:

“Imports account for between 10 to 15 per cent of the (consumer price index), so it can have a significant impact”, AMP chief economist Shane Oliver said.

It means every fall in the Aussie dollar by 10 per cent adds 0.1 to 0.15 per cent to inflation."

Yes and no; Oliver is making the mistake of reasoning from a price change. People don’t suddenly have more money to pay for more expensive imports, which is a relative price shock – e.g. imports go up relative to services.

For higher import prices to cause inflation, the government or RBA must give people more money. If they don’t, people will have to demand less of something else, reducing prices elsewhere with no long-run impact on the price level.

Now, there is of course a difference between measured inflation and actual inflation. In the short run, because of how the CPI is measured and because prices tend to be “sticky” in the downward direction, a weaker Aussie dollar may well “add” to inflation, as measured by the CPI.

I don’t know what the RBA will ultimately choose to do, but it’s probably likely to respond to any temporary measured increase in inflation by remaining relatively hawkish, pushing back whatever rate cut it may or may not have had planned.

Still, cuts are coming

Predicting inflation and monetary policy is difficult because there are various lags and it’s tough to know how people will respond to decisions made by the government and central bank. Moreover, expectations matter; if people start to think prices will go up next year, they’ll start raising them now.

However, the current trend looks relatively benign and so I think a cut is likely in the first half of this year, perhaps as soon as May, largely because monetary policy is working: Australia’s private sector is in recession, crowded out by positive real interest rates and a low-productivity fiscal expansion at all levels of government.

I also question whether our various governments can continue their big spending, inflationary ways for much longer. Growth in China is slowing, and with no new mining boom on the horizon, the bond market is calling for fiscal restraint: Australian 10-year Treasuries are yielding more than nominal GDP growth.

In economic-speak, that means r (interest on debt) minus g (economic growth) is now positive, so the ratio of debt to GDP will increase even if the government suddenly started to run balanced budgets, which it has no intention of doing.

Basically, the bond market is telling the government to ditch Jim Chalmers’ debt-financed “values-based capitalism”, which is code for him supplanting your values with his own, and return to something resembling the standard economic playbook.

Whether he listens or not is another question – but don’t forget what happened to Liz Truss!

Comments

Comments have been disabled and we're not sure if we'll ever turn them back on. If you have something you would like to contribute, please send Justin an email or hit up social media!