Rate cuts are coming soon

The hotly-anticipated December quarter consumer price index (CPI) data were released earlier this morning. Effectively the last official piece of the Reserve Bank of Australia’s (RBA) puzzle ahead of its 18 February rates decision, it’s also the most important.

Breaking it down

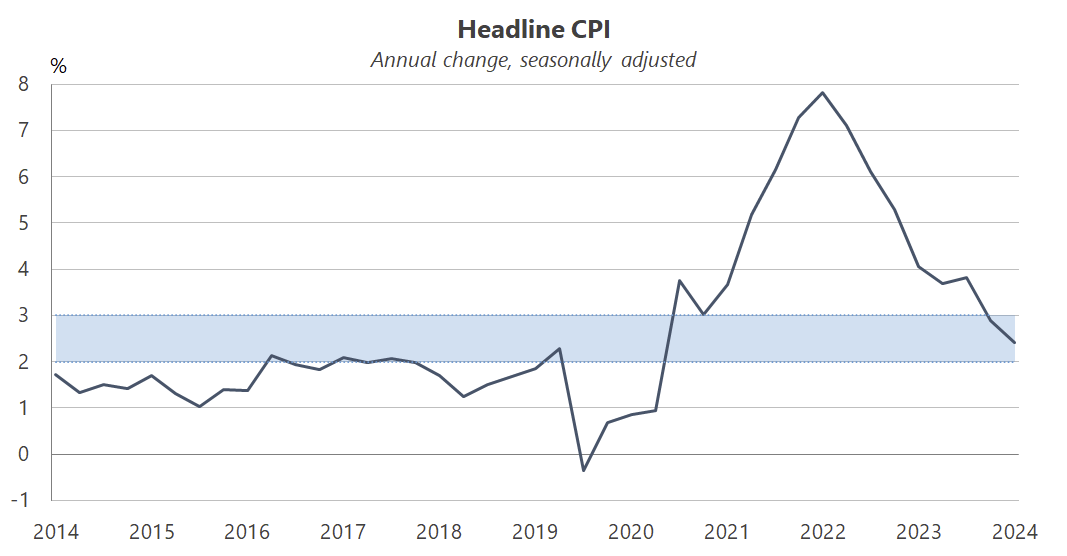

Unlike the monthly data, the quarterly CPI contains price updates for all items in the basket. As has become all too familiar, various government subsidies distorted the headline measure, which came in at 2.4% in the December quarter:

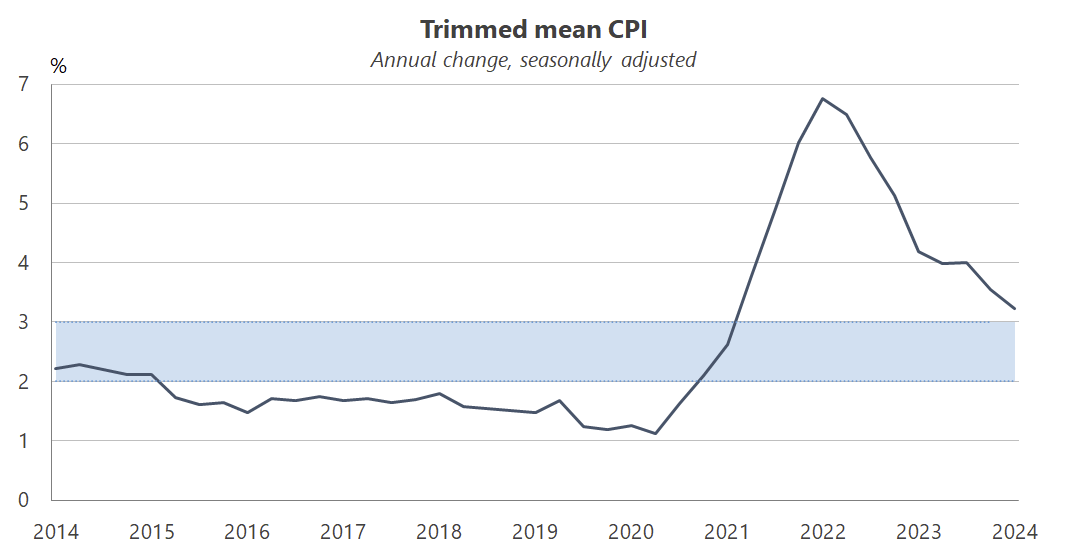

Normally in such a scenario I would bypass the headline figure and look at the trimmed mean measure, which cuts out the bottom and top 15% of price changes, thereby ’looking past’ such distortions. When you’re trying to forecast inflation, looking only at the most stable 70% of prices is a perfectly reasonable thing to do: volatile items are just as likely to move in the other direction in the future, whereas stable prices are a better forecast of future inflation, which is what we care about for predicting possible rate movements.

In the December quarter, the trimmed mean indicator increased by 3.2%, only slightly above the RBA’s target band:

However, there’s one more problem. There are now so many government subsidies coming on and rolling off – energy, rent, public transport, childcare – that even the trimmed mean measure now includes some of the distortions, most notably rents:

“[E]ven with a substantial reduction rental inflation remains in the middle 70% of price changes and impacts the trimmed mean quite often. Even if it does get trimmed out it pushes some other low-inflation subgroup into the non-trimmed middle portion of the distribution which will lower the trimmed-mean inflation rate.”

The CPI’s value as a measurement of inflation has effectively been muted; the government really has proven Goodhart’s law, which predicts that when a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure. It so desperately wanted to get measured inflation down that it made the measure itself unreliable.

However, there is a further option – at least until the December quarter national accounts data are released with broader measures of inflation, which will unfortunately come too late for the RBA’s February meeting.

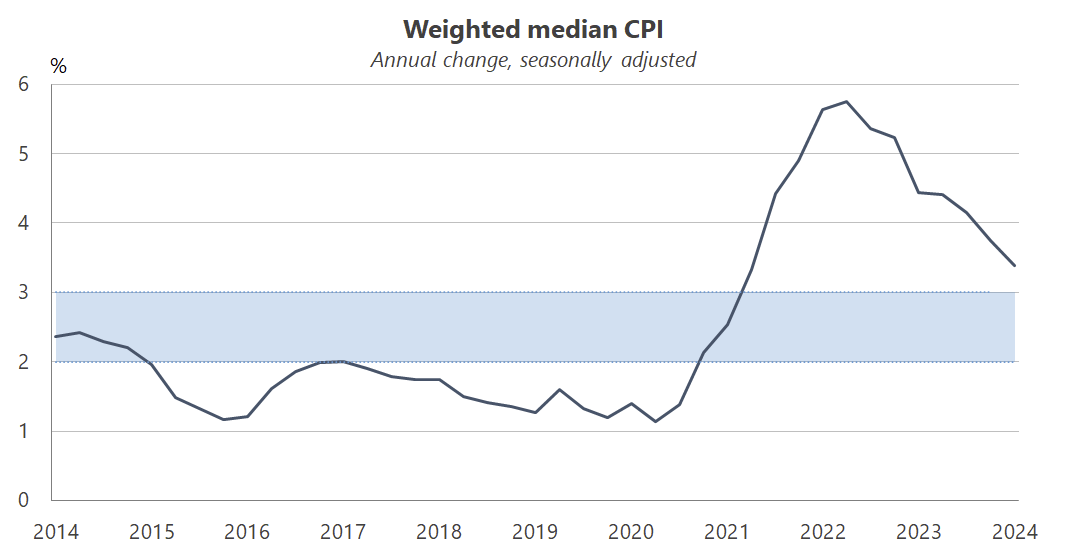

Monash university’s Zac Gross, who has studied the historical data, recommends using the weighted median as it “is a much harder statistic to manipulate and provides a clearer picture of underlying inflation trends”.

It grew at 3.4% in the December quarter and just 0.5% on a quarterly basis:

What’s important is that, despite the manipulations, these indicators are all still trending in the right direction and appear as though they will soon be back within the RBA’s target band.

What it means for interest rates

These data will surely give the RBA the confidence to consider a rate cut in February, especially with the market sector stagnating and inflation easing in several other peer economies. The Aussie dollar fell as the data were released, suggesting markets have also increased their rate cut expectations.

The only possible hurdles are the fact it’s the last meeting before the newly formed board takes over (the old board may not want its last act to be a meaningful change in policy direction), and that the labour market remains very strong.

Unemployment is at 4.0% and trending lower, putting it below any of the RBA’s estimates of the (unobservable and empirically unreliable) non-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment (NAIRU), which it uses as an input for its inflation and wage forecasts. Basically, the RBA’s models will be more likely to show inflation remaining above its 2-3% target if the unemployment rate is below its estimate of the NAIRU, making rate cuts less likely.

Complicating matters is the fact that more than eighty percent of jobs created over the past two years have been in non-market sectors such as healthcare (i.e. NDIS). These jobs are by definition low-productivity service sector jobs, which in a stagnant economy with negative labour productivity growth means they’re likely add more to demand than they do supply, worsening inflation.

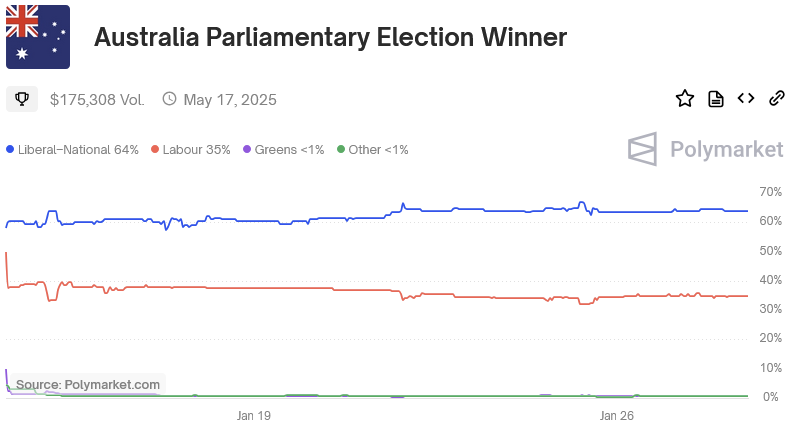

Then there’s the final variable: political pressure. There’s a federal election due sometime between now and May, and the Albanese government is trailing in the polls and on prediction markets:

Treasurer Jim Chalmers channelled his mentor Paul “they do what I say” Keating last year by criticising the RBA for allegedly “smashing” the Australian economy. More recently, even state Premiers have got in on the RBA-influencing act:

“In a letter sent to the RBA board on Saturday, Mr Cook said he believed the economic conditions were right for a cut in interest rates, which have been on hold since November 2023 after 13 hikes since May 2022.”

The ongoing attempts by politicians to influence what is supposed to be an independent institution are disturbing, and hark back to bad old days when the politicisation of central banking led to some seriously poor monetary policy.

But perhaps they’ll get their wish anyway – these quarterly CPI figures mean that the RBA’s February meeting is now very much ’live’, and if I had to guess I would say a rate cut is the most likely outcome.

Comments

Comments have been disabled and we're not sure if we'll ever turn them back on. If you have something you would like to contribute, please send Justin an email or hit up social media!