Solid growth, hidden pressures

The all-important December quarter national accounts data were released this morning. I say all-important because, while a lagging indicator, they still contain a swath of information not available in any other statistical release.

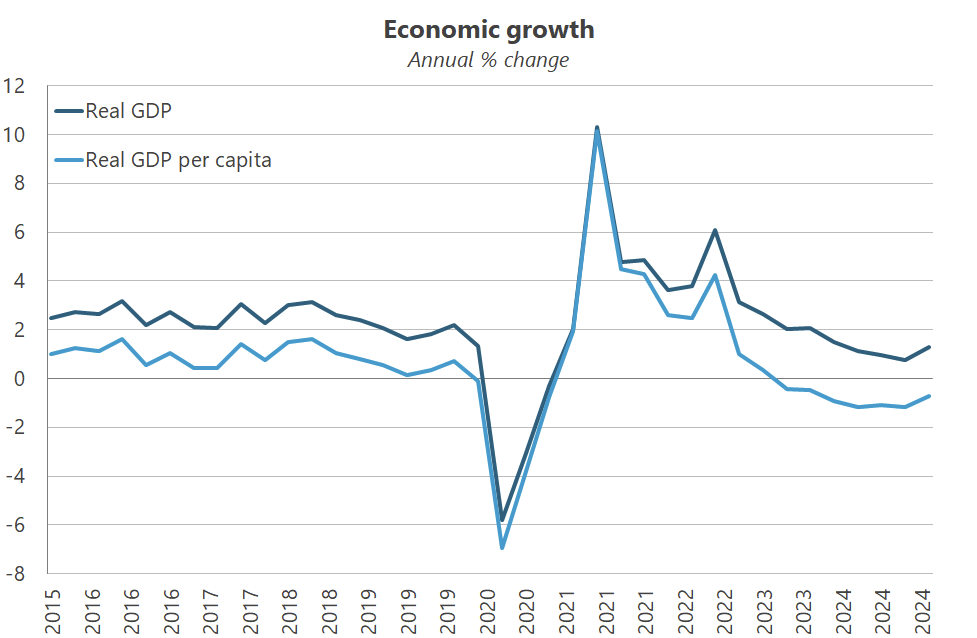

So, what did they show? Real GDP increased by 1.3% from a year ago, while the per capita recession rolled into its seventh consecutive quarter. However, both improved from September and the per capita figure actually increased by 0.1% on a quarterly basis—the first positive movement in two years.

According to the ABS:

“Modest growth was seen broadly across the economy this quarter. Both public and private spending contributed to the growth, supported by a rise in exports of goods and services.”

The rise in exports looks to be Aussie dollar-related, with services—specifically travel—where much of the change occurred. Here’s the ABS again:

“Exports of travel services also increased with overseas travellers benefiting from the depreciation of the Australian dollar against the US dollar. A fall in the import of travel services also contributed to the positive movement in net trade as Australians opted for cheaper and shorter holidays.”

So, Australians travelling overseas less and foreigners spending more time Down Under.

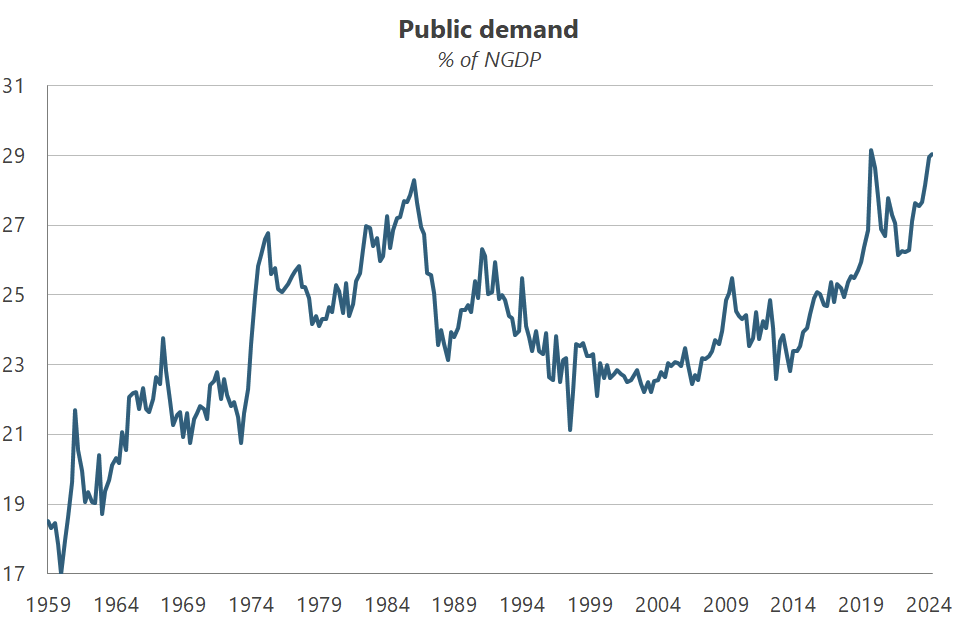

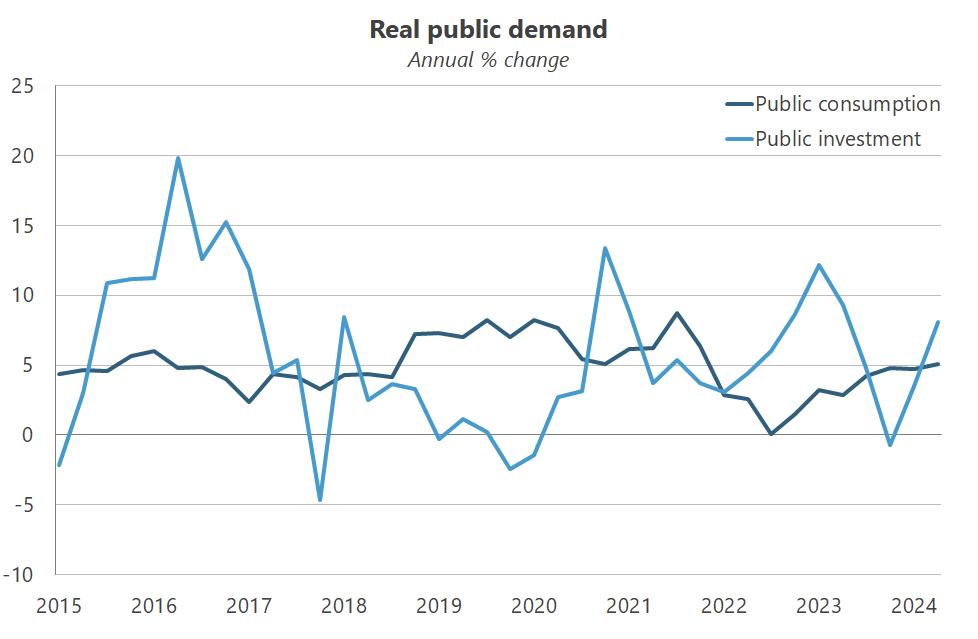

But there were plenty of gremlins in the release, too. State and federal government spending picked up again and was the main contributor to measured growth, with public demand rising close to a new record high 29.0% of GDP—well above the Reserve Bank of Australia’s (RBA) forecast for the quarter.

When you’re trying to get demand-driven inflation down, that’s the opposite of what you want to see in the data.

But that wasn’t even the worst of it.

Wages are robust, productivity… not so much

Earlier this week saw the release of business indicators for the December quarter, with wages and salaries paid growing at a robust 4.7%—the first quarterly acceleration since the high inflationary period of 2022-23.

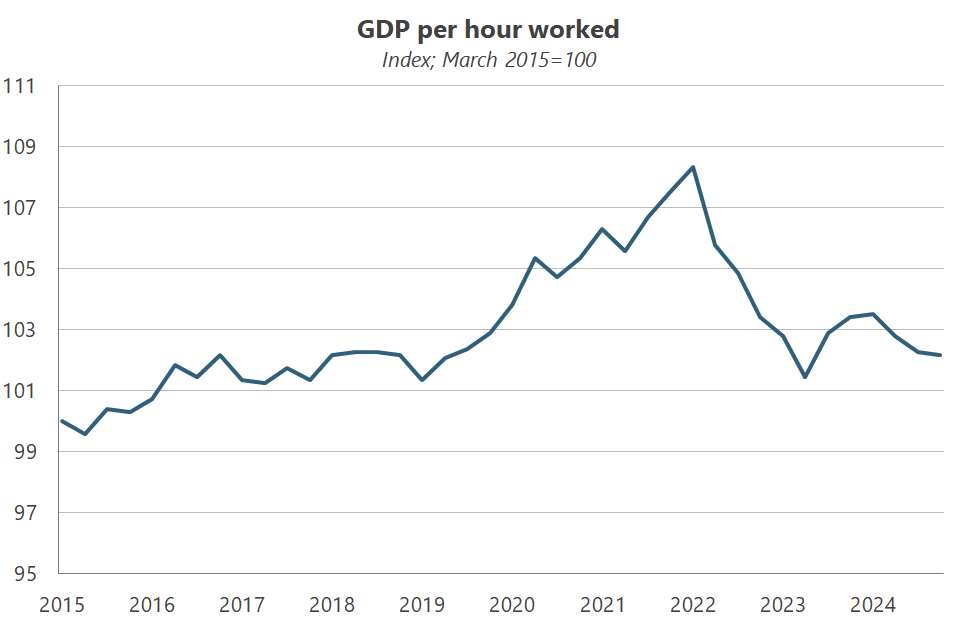

Now, we’ve had a lot of population growth over that period, too. More people, more salaries to be paid—even if those salaries aren’t growing all that quickly. Higher wage payments aren’t necessarily a problem for inflation, provided there’s productivity growth to support it. Alas, as today’s national accounts showed, Australia has seen no productivity growth in recent years, and it declined again in the December quarter.

As I wrote the other week:

“Wages rising faster than productivity don’t necessarily lead to inflation, unless they’re being paid for with new debt that is not expected to be repaid with higher future taxes or lower spending. If that’s the case, it changes behaviour today, aspeople start selling/spending more government debt than they would otherwise, which starts to put pressure on prices.”

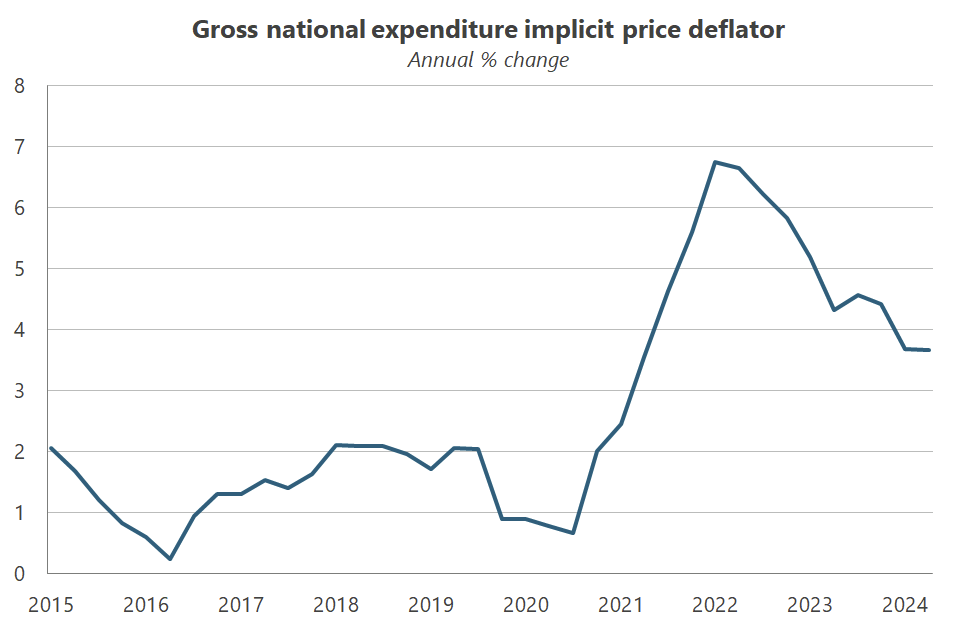

There are a few ways to gauge whether that’s happening. The first is productivity, which we know is falling. The other is to look at the gross national expenditure (GNE) deflator, which strips out trade (commodity price volatility is a big issue in Australia) to focus only on domestic price pressures.

In the December quarter, it was unchanged at 3.7%.

This is all key to the RBA’s thinking. As it wrote last month:

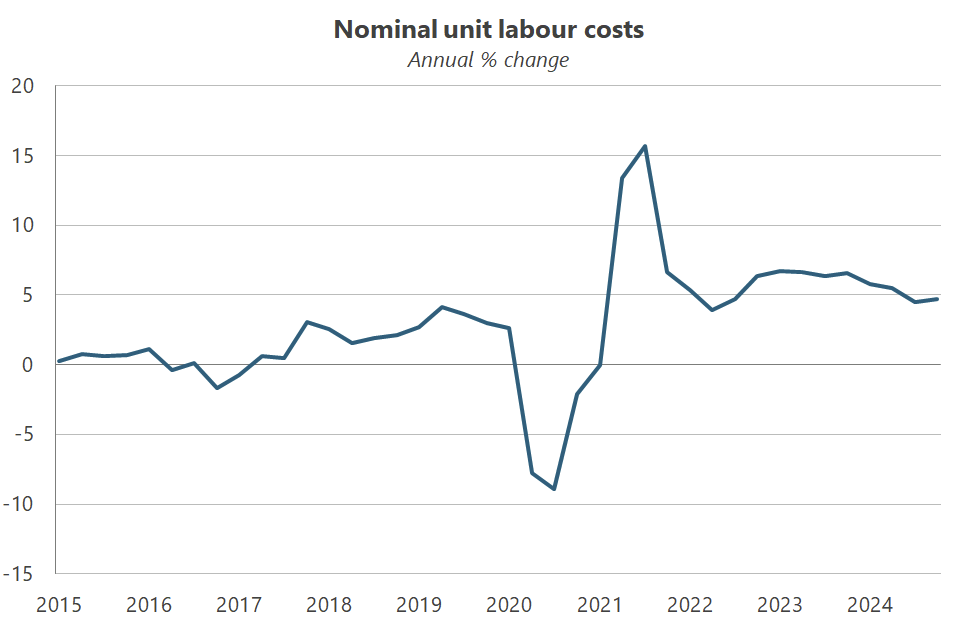

“Overall, solid growth in wages along with still-weak productivity – which is around pre-pandemic levels – has kept growth in unit labour costs above rates consistent with inflation being at target… [however this] is expected to moderate from elevated levels as productivity growth picks up.”

That’s a lot of weight to put on productivity growth that has been all but absent in Australia in recent years, and with no meaningful policy response on the horizon, the RBA looks to be praying for a miracle. And so far that miracle hasn’t come, with unit labour costs rising in the December quarter at a rate that would not be consistent with its 2-3% target:

Basically, domestic cost pressures (e.g. labour) are being driven up faster than output efficiency, and if firms start to pass those higher costs on, then the RBA might miss its target.

Basically, domestic cost pressures—like labour—are rising faster than output efficiency. This means unit labour costs (what firms pay workers per unit of output) are growing, and if firms pass those higher costs onto consumers, then measured inflation might prove to be sticky.

Earlier today the RBA’s deputy governor Andrew Hauser gave a speech in which he said as much, observing that while nominal wage growth had eased a little, “with measured productivity growth as weak as it has been recently, that still implies elevated growth in companies’ unit labour costs”.

Hauser knows that there are only two ways to achieve his inflation target: tighter monetary and fiscal policy, i.e. fewer dollars chasing the same number of goods, or higher productivity (output), i.e. the same number of dollars chasing more goods.

These data are lagged (December quarter) but it won’t have made for good reading for the boffins at the RBA.

Other indicators of demand are holding up

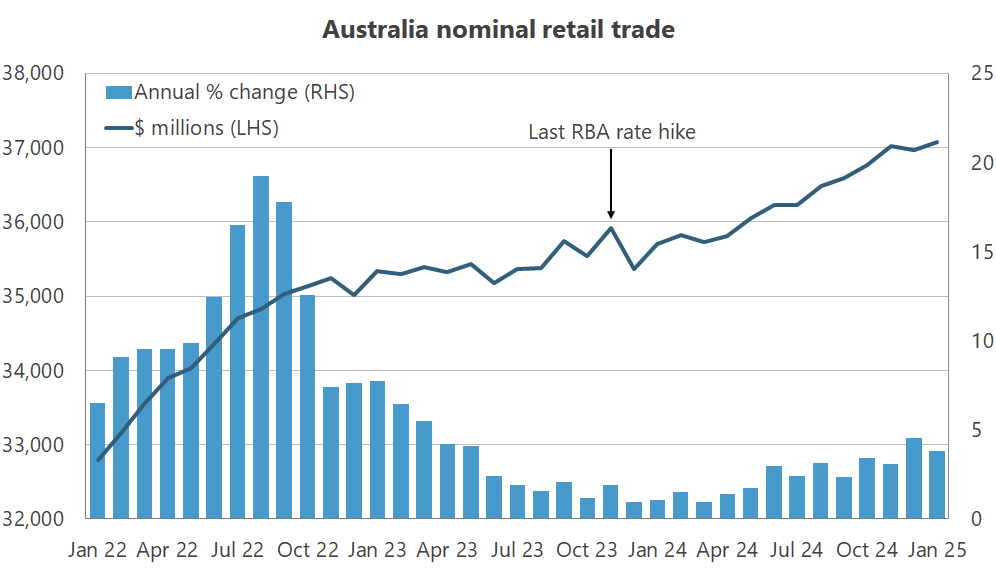

I’m just quickly going to touch on some higher frequency data that were released earlier this week. First was retail sales, with January’s figures continuing their run of recent strength, rising a solid 3.8%:

Next was CoreLogic’s Home Value Index, which showed house prices rising 0.3% in February from January—equivalent to an annualised rate of 3.7%)—“as the first rate cut in over four years lifted buyer sentiment”.

Put those together with the robust labour market and the December quarter data and there’s little evidence that this is an economy crying out for monetary easing.

Where to for rates?

In the Minutes of the RBA’s last meeting, its board members said that they would be “guided by the incoming data and evolving assessment of risks”, and that nothing was off the table:

“[I]f the evolving data signalled that inflation was proving more persistent than expected, it would be reasonable to maintain a more restrictive stance of policy by holding the cash rate at 4.1 per cent for an extended period… or by even tightening policy if the outlook was for inflation to rise materially.”

We’ve now had official data for retail sales, business indicators, and the December quarter national account since that meeting was held. Other than what it collects through its engagement program and private releases like CoreLogic’s, there are only two significant official data releases before the next meeting: the labour force and monthly inflation for February.

Barring something dramatic in those releases—or further Trumpian uncertainty, which the RBA admitted “played a part in the Board’s policy deliberations in February”—the most likely outcome is for inflation to remain elevated and rates to stay at 4.1% for an extended period.

Comments

Comments have been disabled and we're not sure if we'll ever turn them back on. If you have something you would like to contribute, please send Justin an email or hit up social media!