The end of Trudeau

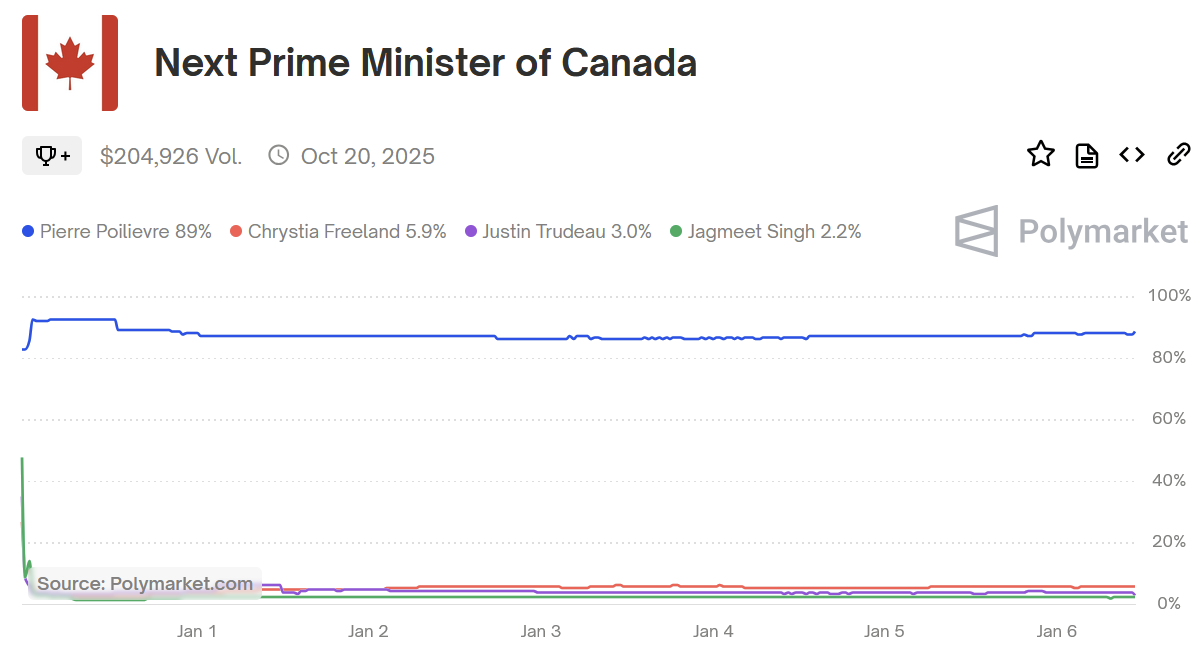

Canada’s Prime Minister, Justin Trudeau, has resigned after a decade in the top job, having lost the support of his own party ahead of what is shaping up to be a landslide victory for the Conservative opposition later this year.

I know I’ve got some Canadian readers, along with plenty of Australians who have an interest in the country given the cultural and economic similarities, so I thought it would be worth taking a quick look at how it all went wrong for Trudeau and what it might mean for Australia.

The realigning election

Justin Trudeau was first elected as Prime Minister in 2015 in a somewhat surprising result – his Liberal party (ideologically equivalent to Australia’s Labor party) was third place in pre-election polling, before pulling off a stunning late surge to secure a majority government – its first in 15 years.

The victory was less about Trudeau’s Liberals and more to do with people’s immense dislike of the incumbent Conservative party Prime Minister, Stephen Harper. Despite the big win, the honeymoon would only last a single term.

By the time the 2019 election rolled around, Canada’s economy had well and truly soured and Trudeau ultimately managed to secure just 33.12% of the popular vote, the lowest share for a single-party ruling government in Canada’s history. Its ability to govern henceforth depended on the support of the far-left New Democratic Party or French nationalist Bloc Québécois, making life very difficult for Trudeau.

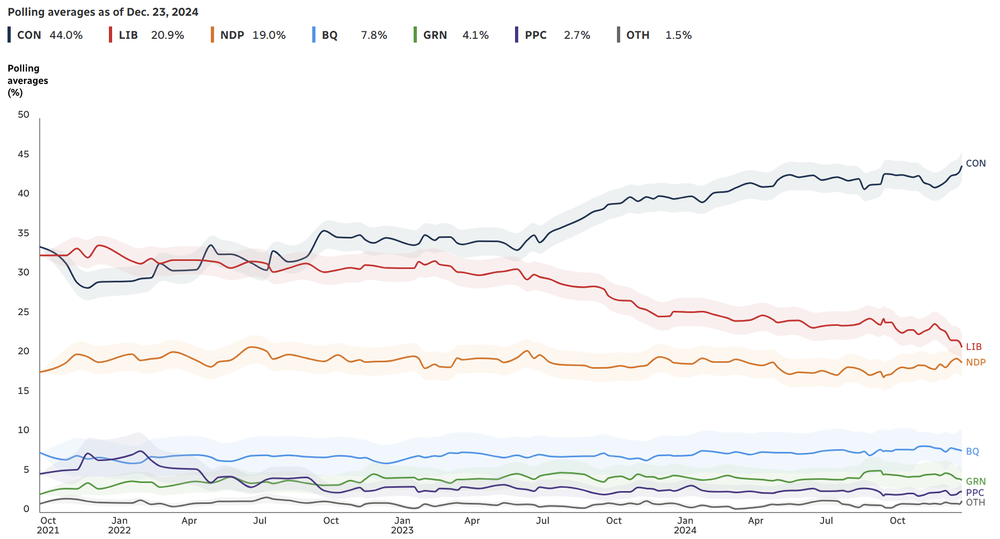

Frustrated by the minority government and hoping to benefit from the pandemic boost that incumbent governments around the world were enjoying at the time, Trudeau called another election just two years later. But this time the result was even worse for his Liberals, which set a new record for the lowest vote share for a party that would go on to form a single-party minority government (32.6% of the popular vote).

Since then it has been all downhill for Trudeau, both politically and economically.

Canada’s economic malaise

In economics, almost everything is multi-causal; there are several variables that work together (and in opposition) that lead to certain outcomes. But voters like simple narratives, and a big problem Trudeau had was that a lot of Canada’s own problems started to get a lot worse in 2015, which also happens to be when he was first elected.

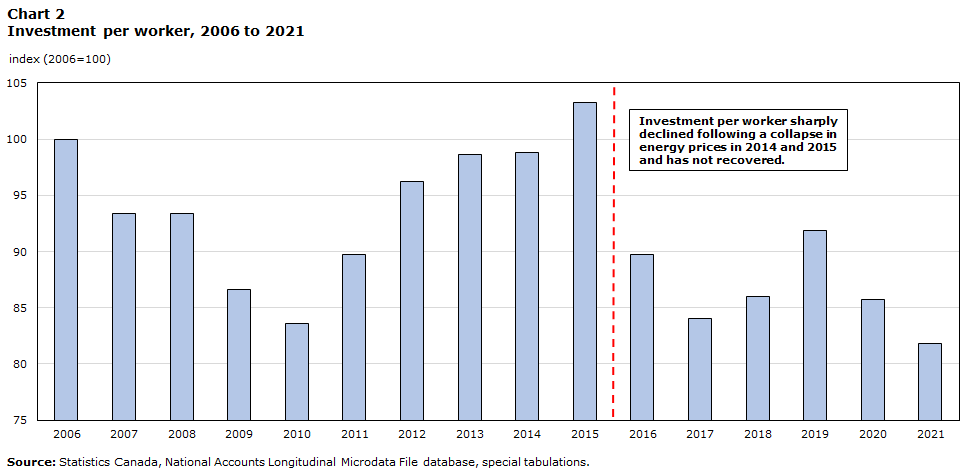

Most notably, there was a large, permanent drop in investment per person in 2016 following a collapse in energy prices during China’s last slowdown and the rapid growth in Canada’s population:

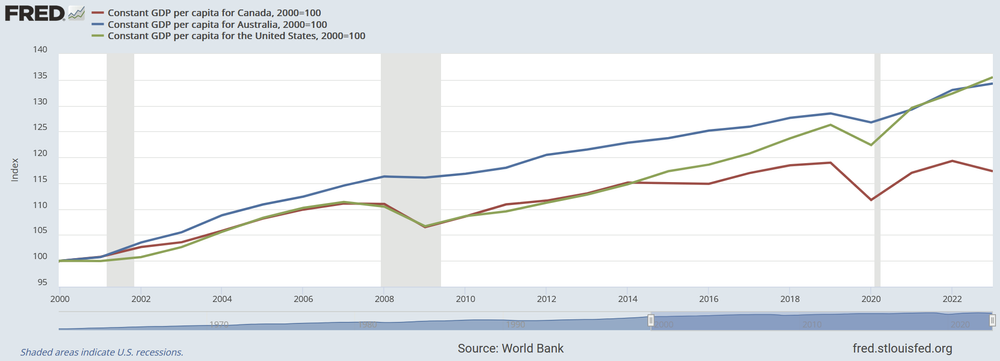

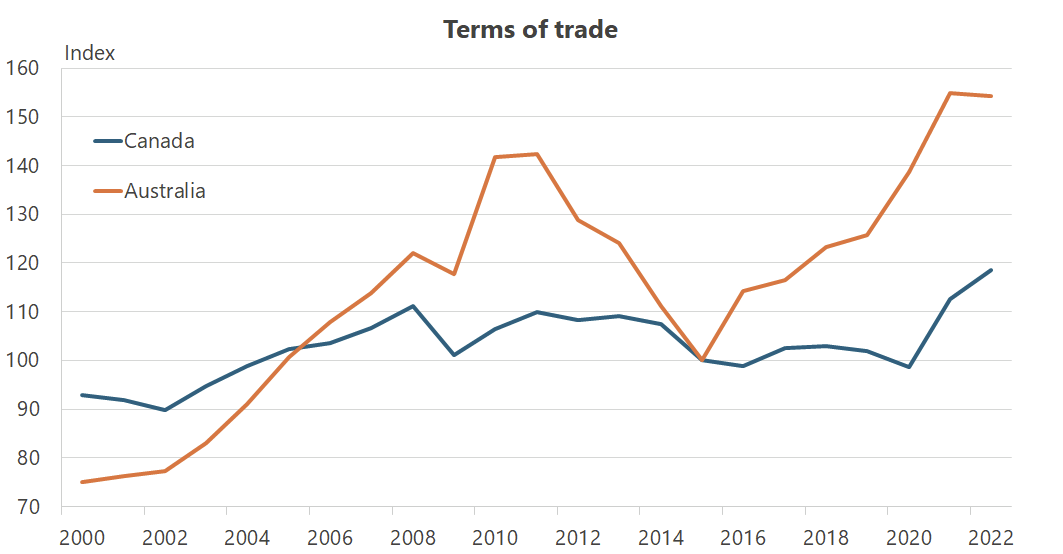

It’s difficult to grow without investment, and Canada’s GDP per capita has underperformed peers like Australia and the US ever since, largely due to a chronic lack of productivity growth but without the good fortune of a new mining boom to rescue them:

Many of the causes of Canada’s low productivity growth have their origins from well before Trudeau. It’s a relatively inefficient, cartelised economy, with monopolies everywhere you look.

But rather than embracing productivity-enhancing reforms, Trudeau’s solution was to create a “big Canada”, figuring he could just grow the country out of stagnation by adding more people. The change of Canada’s successful migration system to one “of quantity over quality” has proved deeply unpopular with voters, in part because the country’s ability to absorb more people is also constrained by many of the forces that have stifled productivity, such as regulations that restrict the ability to build housing.

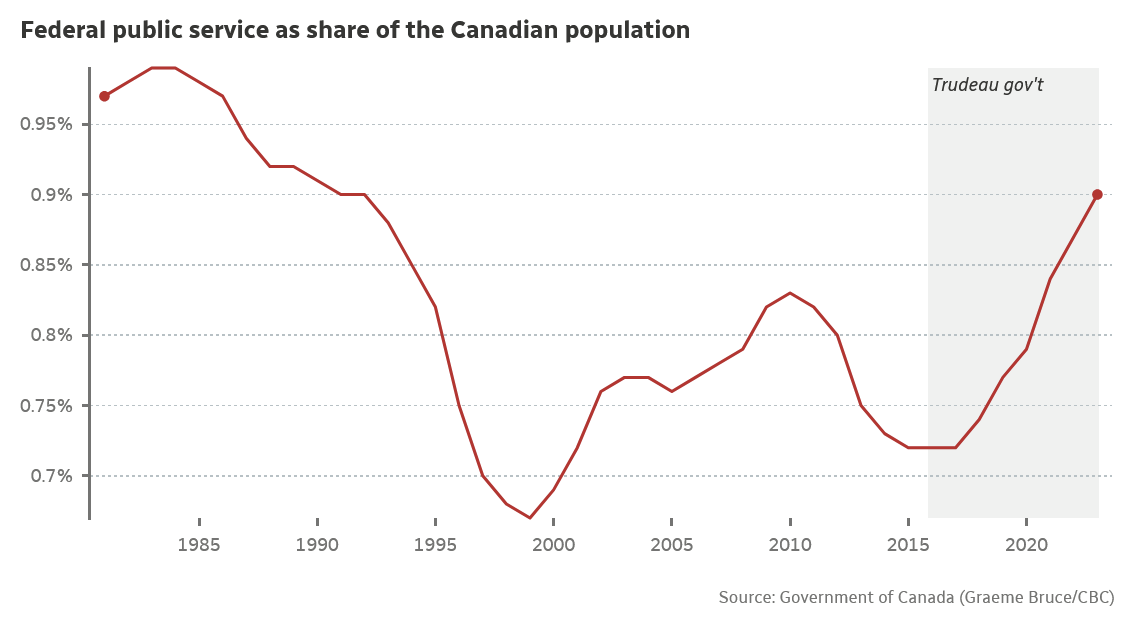

Moreover, Trudeau has increased the relative size of the public service, and per capita federal spending is now at an all-time high, financed with debt that is contributing to Canada’s own cost of living, inflationary crisis.

As in Australia, Canada’s aging population might require society to spend a bit more on services provided by the government – health care, for example – but doing so increases the need to improve productivity elsewhere. When you’re putting that spending on the nation’s credit card, that urgency becomes even greater.

Lessons for Albo

The best way to finance social programs and other spending aspirations is through economic growth. If you don’t combine significant changes in spending with productivity-enhancing reforms, you’re effectively making a judgement call that people value what you’re spending on more than what they want to spend on.

In Canada, the people just aren’t all that keen on Trudeau’s priorities, and he has paid the price.

Back at home, the Albanese government has also ratcheted up spending since assuming office:

“In the coming financial year, the government’s decisions since coming to office have added just short of $30 billion, or more than 1 per cent of GDP, to the deficit, taking it to $47 billion. Over the six years that its first five budget updates covered, its decisions have added a total of $78 billion, or 2.7 per cent of GDP, to the national debt.”

If I was giving the Albanese government advice, it would have been to do precisely the opposite of the above. That is, cut spending to ease pressure on inflation – which affects all households – and to ensure that when the next shock inevitably hits, we have the fiscal capacity to manage without causing another bout of inflation.

That, and to focus almost entirely on getting productivity moving again. People don’t like being made poorer, and if there’s no future China stimulus to get mining (and therefore aggregate) productivity moving again, then whomever is in power might soon find themselves suffering the same fate as Trudeau.

Comments

Comments have been disabled and we're not sure if we'll ever turn them back on. If you have something you would like to contribute, please send Justin an email or hit up social media!